The Japanese Experience with Railway Restructuring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Japan Railway Company Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto

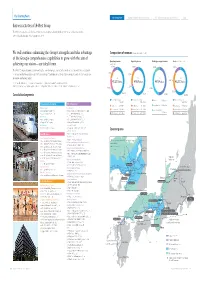

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 For the year ended March 31, 2017 Pursuing We have been pursuing initiatives in light of the Group Philosophy since 1987. Annual Report 2017 1 Tokyo 1988 2002 We have been pursuing our Eternal Mission while broadening our Unlimited Potential. 1988* 2002 Operating Revenues Operating Revenues ¥1,565.7 ¥2,543.3 billion billion Operating Revenues Operating Income Operating Income Operating Income ¥307.3 ¥316.3 billion billion Transportation (“Railway” in FY1988) 2017 Other Operations (in FY1988) Retail & Services (“Station Space Utilization” in FY2002–2017) Real Estate & Hotels * Fiscal 1988 figures are nonconsolidated. (“Shopping Centers & Office Buildings” in FY2002–2017) Others (in FY2002–2017) Further, other operations include bus services. April 1987 July 1992 March 1997 November 2001 February 2002 March 2004 Establishment of Launch of the Launch of the Akita Launch of Launch of the Station Start of Suica JR East Yamagata Shinkansen Shinkansen Suica Renaissance program with electronic money Tsubasa service Komachi service the opening of atré Ueno service 2 East Japan Railway Company Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto Shin-Aomori 2017 Hachinohe Operating Revenues ¥2,880.8 billion Akita Morioka Operating Income ¥466.3 billion Shinjo Yamagata Sendai Niigata Fukushima Koriyama Joetsumyoko Shinkansen (JR East) Echigo-Yuzawa Conventional Lines (Kanto Area Network) Conventional Lines (Other Network) Toyama Nagano BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) Lines Kanazawa Utsunomiya Shinkansen (Other JR Companies) Takasaki Mito Shinkansen (Under Construction) (As of June 2017) Karuizawa Omiya Tokyo Narita Airport Hachioji Chiba 2017Yokohama Transportation Retail & Services Real Estate & Hotels Others Railway Business, Bus Services, Retail Sales, Restaurant Operations, Shopping Center Operations, IT & Suica business such as the Cleaning Services, Railcar Advertising & Publicity, etc. -

West Japan Railway Group Integrated Report 2019 —Report on Our Value for Society—

Continuity Progress Making Our Vision into Reality West Japan Railway Group Integrated Report 2019 —Report on Our Value for Society— West Japan Railway Company Contents 2 On the publication of “JR-West Group Integrated Report 2019” 3 Values held by the JR-West Group Our Starting Point 5 The derailment accident on the Fukuchiyama Line 11 Recovering from heavy rain damage through cooperation and think-and-act initiatives 13 Business activities of JR-West Group 15 The president’s message 17 The value we seek to provide through the non-railway business —Messages from group company Presidents Strategy of 21 Steps toward our vision 21 JR-West Group Medium-Term Management Plan 2022: approach & overview Value Creation 23 Toward long-term sustainable growth for Our Vision 25 Progress on Groupwide strategies—example initiatives 27 Promoting our technology vision 29 Special Three-Way Discussion The challenge of evolving in the railway/transportation field in an era of innovation 33 Fiscal 2019 performance in priority CSR fields and fiscal 2020 plans for priority initiatives 37 Safety 47 Customer satisfaction 51 Coexistence with communities A Foundation 55 Human resources/motivation Supporting 59 Human rights Value Creation 61 Global environment 67 Risk management 71 Corporate governance 73 Special Three-Way Discussion The role of the Board of Directors in achieving sustainable growth and enhancing corporate value 77 Initiatives in each business 81 Consolidated 10-year financial summary Data 83 Financial statements 87 Recognizing and responding to risks and opportunities 88 Data related to human resources and motivation (non-consolidated) Corporate profile (as of March 31, 2019) Scope As a rule, JR-West Group (including some Company name West Japan Railway Company initiatives at the non-consolidated level). -

RESTRICTED GPA/MOD/JPN/86 27 July 2016 (16-3988) Page: 1/2

RESTRICTED GPA/MOD/JPN/86 27 July 2016 (16-3988) Page: 1/2 Committee on Government Procurement Original: English PROPOSED MODIFICATIONS TO APPENDIX I OF JAPAN UNDER THE REVISED AGREEMENT ON GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT COMMUNICATION FROM JAPAN Replies from Japan to the questions from Canada (GPA/MOD/JPN/84) to its proposed modifications circulated in GPA/MOD/JPN/82 The following communication, dated 26 July 2016, is being circulated at the request of the Delegation of Japan. _______________ RESPONSE FROM JAPAN TO QUESTIONS FROM CANADA (GPA/MOD/JPN/84) TO ITS PROPOSED MODIFICATIONS CIRCULATED IN GPA/MOD/JPN/82 Please find below Japan's response to questions from Canada (GPA/MOD/JPN/84) regarding the proposed modification to Appendix I of Japan under the revised GPA (GPA/MOD/JPN/82) related to Kyushu Railway Company. 1. In paragraph 2 e. of its communication, Japan mentions that JR Kyushu is now financially independent. However, Canada notes that JR Kyushu has been granted a management stabilization fund of 3,877 billion yen from the national government, which will continue to subsidize the company beyond 1 April 2016. Furthermore, and contrary to what was done for the East, Central and West Japan Railway Companies, JR Kyushu is not required to reimburse the management stabilization fund to the Government of Japan. How does this fund affect the classification of JR Kyushu as a "financially independent" entity? Can the Government of Japan ask for reimbursement of the management stabilization fund in the future? At the time of the division and privatization of Japan National Railways, the Management Stabilization Fund was established in Kyushu Railway Company, Hokkaido Railway Company and Shikoku Railway Company respectively in order to stabilize their business with the investment profit of the Fund. -

Track Measurement by Kyushu Shinkansen Cars in Commercial Service

Computers in Railways XII 147 Track measurement by Kyushu Shinkansen cars in commercial service H. Moritaka1 & T. Matsumoto2 1Omuta Track Maintenance Depot, Kyushu Railway Company, Japan 2Track Maintenance Division, Track & Facilities Department, Kyushu Railway Company, Japan Abstract The Kyushu Railway Company (JR [Japan Railway] Kyushu) has introduced, for the first time in Shinkansen trains in Japan, a device that can measure all track irregularity using cars in commercial service. With that, special measurement cars were no longer needed, and frequent monitoring of the status of tracks became possible. The track irregularity measurement device employs an inertial measurement method, whereby track irregularity can be measured at a single cross-section. It is mounted with a special attachment base at the center of the bogie frame on rear bogies of the lead cars at both ends of the train. Measurement operations are done by remote control from PCs at the wayside. Devices that can measure track irregularity, body vibration acceleration, and axle box vibration acceleration were mounted to Shinkansen cars in commercial service introduced in August 2009, and use of the devices commenced. Those cars have run 458,299 km as of the end of April 2010, and track measurement was made without problems in the 27,412 km for which measurements were taken. Keywords: Kyushu Shinkansen, track measurement by Kyushu Shinkansen cars in commercial service, the inertial versine method. 1 Introduction The Kyushu Railway Company (JR [Japan Railway] Kyushu) has been proceeding since FY 2005 with the technical development of measurement functions for track irregularity, vibration acceleration, and axle box vibration acceleration to add to Shinkansen cars in commercial service. -

Kyushu Railway Company Green Bond

R&I Green Bond Assessment Aplir 09, 2021 Kyushu Railway Company ESG Division Green Bond: GA1 (Formal) Chief Analyst: Takeshi Usami Rating and Investment Information, Inc. (R&I) has assigned an R&I Green Bond Assessment for the financial instrument of Kyushu Railway Company (JR Kyushu) . R&I announced a preliminary assessment for this instrument on March 15, 2021. ■Overview of R&I Green Bond Assessment Financial Instrument Kyushu Railway Company 8th unsecured corporate bonds (with inter- bond pari passu clause) (green bond) Issue Amount (JPY) JPY 20,000 Issue Date Aplir 15,2021 Maturity Date Aplir 15,2031 Use of proceeds Clean transportation/Green buildings Assessment GA1 (Formal) Assessment by item Item Assessment Use of proceeds Process for project evaluation and selection Management of proceeds Reporting Environmental activities of the issuer * Each item is assessed on a 5-point scale, from (highest) to (lowest). Overall assessment The proceeds from the green bond will be fully allocated to energy-saving train cars and railway-related facilities for clean transportation, as well as green buildings. These initiatives will contribute to the reduction of CO2 emissions by consuming energy more efficiently to ‘address environmental issues (climate change and resource conservation)’ which is one of the materiality points advocated by JR Kyushu. R&I has judged that sufficient consideration is given to negative impacts on the environment and society and that they would contribute to considerable CO2 reduction as a whole. The criteria for selecting projects are clearly defined. Eligible projects selected are considered to be in line with the basic principle and policies of the global environmental conservation activities as determined by JR Kyushu. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2003 CORPORATE DATA (As of March 31, 2003)

GLOSSARY Commuter pass: Shinkansen lines under the Nationwide Shinkansen Railway “Commuter pass” refers to a credit card-sized pass that is either Development Law (see “Shinkansen”) and other national projects. magnetically encoded or contains an integrated circuit (IC) chip Within JR East’s service area, JRCC is presently building Hokuriku and which allows travel between two stations during a period of Shinkansen and Tohoku Shinkansen extensions. JR East rents one, three or six months. Takasaki-Nagano segment of Hokuriku Shinkansen line, opera- tionally named Nagano Shinkansen, and Morioka-Hachinohe seg- Hybrid Shinkansen: ment of Tohoku Shinkansen line from JRCC. JR East also rents “Hybrid Shinkansen” refers to intercity rails systems, which pro- some conventional lines from JRCC. The “Law for Disposal of Debts vide through-service to certain destinations that are not part of a and Liabilities of the Japanese National Railways Settlement regular Shinkansen (as defined below) network, using specially Corporation” was enforced in October 1998. This resulted in the designed trains capable of running on both Shinkansen lines and liquidation of the JNRSC and the transfer of JR East shares held by conventional lines that have been widened to a standard gauge. the JNRSC to JRCC’s JNR Settlement Headquarters. In June 2002, Hybrid Shinkansen lines are not covered by the Nationwide JRCC sold all remaining shares (500 thousand) to the public. Shinkansen Railway Development Law. Number of passengers: JNR: “Number of passengers” includes both passengers who begin their “JNR” means the Japanese National Railways, the Government- journey at the JR East station and passengers who transfer to JR owned public entity that was restructured into JNRSC (as defined East from other railway company lines at the station. -

Kyushu Railway Company Accident Type

Railway accident investigation report Railway operator: Kyushu Railway Company Accident type: Train derailment Date and time: About 22:00, October 14, 2012 Location: Around 396,547m from the origin in Mojiko station, in the premises of Kagoshima-Chuo station, Kagoshima Line, Kagoshima City, Kagoshima Prefecture. SUMMARY The inbound local 2476M train, one-man operated two vehicle train set, starting from Kagoshima-Chuou station bound for Sendai station of Kagoshima Line, Kyushu Railway Company, departed from Kagoshima-Chuou station on schedule, at 22:00, October 14, 2012. The train passed the left curve at about 25 km/h after departure. The train driver noticed the scream of the passengers when the front of the train passed the No.79-Ro turnout. As the train driver checked rear of the train he found the gangway bellows leaned to right considerably, then he applied the brake to stop the train. The train driver checked the situation of the train and found that the rear bogie of the second vehicle was on the track different from the scheduled route and the second axle derailed to the right. There were 157 passengers and a crew on board the train but there was no injured person. PROBABLE CAUSES It is somewhat likely that the first axle in the rear bogie of the second vehicle of the train climbed up the outside rail, i.e., right rail, of the left curved track and derailed to the right of the outside rail, and the second axle dragged by the first axle derailed to the right, in this accident. -

Business Activities of JR-West Group (PDF, 1161KB)

Our Starting Point Our Starting Point Strategy of Value Creation for Our Vision A Foundation Supporting Value Creation Data Business activities of JR-West Group The JR-West Group consists of West Japan Railway Company, 64 consolidated subsidiaries, 88 non-consolidated subsidiaries, and 22 affiliated companies. (As of September 1, 2019) We will continue enhancing the Group’s strengths and take advantage Composition of revenues Year ended March 31, 2019 of the Group’s comprehensive capabilities to grow with the aim of Operating revenues Operating income Railway passenger revenues Assets (As of March 31, 2019) achieving our vision—our ideal forms. (external sales) 11.9% 10.7% 12.4% 14.1% The JR-West Group and its employees all work together in wide-ranging business activities, which include transportation services based 9.7% on railways and lifestyle-related services that take advantage of the features of our transportation services. In addition to this, we also work 17.9% to develop new business sectors. Total Total Total Total 20.1% billion billion billion billion No *: Consolidated subsidiaries *: Non-consolidated subsidiaries **: Companies accounted for using the equity method ¥1,529.3 ¥196.9 ¥873.4 ¥3,237.5 Note: Company names in each business segment are listed according to the main business activities. The names of the main companies only are listed. 3.1% 16.1% 35.3% 3.5% 62.4% Consolidated segments 68.3% 52.3% 62.3% Transportation operations Transportation operations Transportation operations Shinkansen ¥457.0 billion ¥953.9 billion ¥136.2 billion ¥2095.0 billion Transportation Operations Other Businesses Retail business ¥245.5 billion Retail business ¥6.1 billion Kansai Urban Area ¥308.1 billion Retail business ¥118.2 billion Railway Services Hotel Business Real estate business ¥148.5 billion Real estate business ¥35.6 billion Other conventional lines Real estate business ¥675.7 billion West Japan Railway Company West Japan Railway Hotel Development Limited ¥108.2 billion Sagano Scenic Railway Co., Ltd. -

Railway Technologies & Services Japan Market Study

Railway Technologies & Services Japan Market Study JULY 2019 © Copyright EU Gateway | Business Avenues The information and views set out in this study are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of EU Gateway | Business Avenues and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The purpose of this report is to give European companies selected for participation in the EU Gateway | Business Avenues Programme an introductory understanding of the target markets countries and support them in defining their strategy towards those markets. For more information, visit www.eu-gateway.eu. EU Gateway to Japan Central Management Unit Japan Market Study July 2019 Submitted to the European Commission on 22 July 2019 Railway Technologies & Services - Japan Market Study - Page 3 of 143 Table of contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................................ 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................. 9 2. WHAT ARE THE CHARACTERISTICS OF JAPAN? ......................................................................................... -

2011 Annual Report

GROUP STRATEGY REVIEW OF OPERATIONS AS A CORPORATE CITIZEN DOMESTIC AND INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES FINANCIAL SECTION TION C For the year ended March 31, 2011 Annual Report 2011 ONSTRU C E R CREATIVE CREATIVE KEY FIGURES TO BETTER UNDERSTAND JR EAST *Figures are as of March 31, 2011 Consolidated operating revenues, ¥2,537.4 billion On a daily basis about 17 million passengers travel a network of 70 train lines stretching 7,512.6 operating kilometers 92 stations are used by more than 100,000 passengers a day Total safety-related investments in the 24 years since JR East’s founding, about ¥2.5 trillion Open inside cover Jr east’s serVICE AREA TOKYO The new Hayabusa Series E5 super express railcars on the Tohoku Shinkansen Line will ultimately operate at a maximal speed of 320km/h Retail stores and restaurants in the stations, about 2,500 The number of Suica prepaid, rechargeable IC cards issued, about 35 million About 140,000 Open inside cover stores accept Suica electronic money Annual Report 2011 001 East Japan Railway Company (JR East) is the largest passenger railway company in the world, serving about 17 million passengers daily. JR East operates a five-route Shinkansen network between Tokyo and major cities in eastern Honshu (Japan’s main island). JR East has the ability to leverage passenger traffic and railway assets to develop non-transportation businesses. JR East alone provides nearly half of the huge volume of railway transportation in the Tokyo metropolitan area. HISTORY OF JR EAST April 1987 July 1992 March 1997 The Fukushima–Yamagata segment of the Yamagata Hybrid Shinkansen Line opens and the Tsubasa super-express begins service, marking the first Shinkansen through service to a conventional line. -

Smartcard Ticketing Systems for More Intelligent Railway Systems

Hitachi Review Vol. 60 (2011), No. 3 159 Smartcard Ticketing Systems for More Intelligent Railway Systems Yuichi Sato OVERVIEW: The smartcard ticketing systems whose scope is expanding Masakazu Ito across Japan are now starting to be used not just for public transport Manabu Miyatake ticketing services but also to provide users with an infrastructure that they use in their daily lives including electronic money and mobile services, credit card integration, building access control, and student identification. Hitachi has already contributed to this process through the development and implementation of smartcard ticketing systems for different regions and is now working on the development of systems that support the implementation of smart systems that underpin society and combine information and control to provide new social infrastructure for the foreseeable future. INTRODUCTION TABLE 1. Smartcard Ticketing Systems in Japan A number of smartcard ticketing systems have been Smartcard ticketing systems have spread right across Japan introduced in different parts of Japan since the over the last 10 years. *1 Service Smartcard Suica service of the East Japan Railway Company Operator commenced operation in November 2001. As of March commenced name* 2009, systems of this type had been introduced at November, 2001 Suica East Japan Railway Company Nagasaki Transportation Bureau of Nagasaki January, 2002 about 25 companies including both JR (Japan Railway) Smartcard Prefecture and others IC Saitama Railway Co., Ltd. (switched to Group and private railway companies (see Table 1). March, 2002 The East Japan Railway Company is the leader TEIKIKEN PASMO) Monorail April, 2002 Tokyo Monorail Co., Ltd. in this field and its aims in introducing the Suica Suica service include providing its passengers with greater July, 2002 Setamaru Tokyu Corporation convenience, facilitating cashless operation at railway December, 2002 Rinkai Suica Tokyo Waterfront Area Rapid Transit, Inc. -

2009 Annual Report

WEST JAPAN RAILWAY COMPANY RAILWAY JAPAN WEST Annual Report 2009 Ensuring Safety, Delivering Growth Annual Report 2009 WEST JAPAN RAILWAY COMPANY WEST JAPAN RAILWAY COMPANY Printed in Japan West Japan Railway Company (JR-West) is one of the six passenger railway transport companies formed by the split-up and privatization of Japanese National Railways (JNR) in 1987. Its mainstay railway business operates a network of lines with a total route length of approximately 5,000 kilometers, extending through 18 prefectures that account for around one-fifth of Japan’s land area. Railway systems in Japan evolved as a natural consequence of the cities that formed through the accumulation of people in the limited number of plains throughout the country. Joined like links in a chain, the geographical distribution of these cities has created a solid demand base that accounts for one-fourth of all passenger volume in Japan. While railway operations remain the core of its business, JR-West also aims to make the most of the assets that are part of its network of stations and railways to develop its retail, real estate, and hotel businesses. Corporate Philosophy 1 We, being conscious of our responsibility for protecting 4 We, together with our Group companies, will consistently the truly precious lives of our customers, and incessantly improve our service quality by enhancing technology and acting on the basis of safety first, will build a railway that expertise through daily efforts and practices. assures our customers of its safety and reliability. 5 We, deepening mutual understanding and respecting each 2 We, with a central focus on railway business, will fulfill the individual, will strive to create a company at which employ- expectations of our customers, shareholders, employees, ees find job satisfaction and in which they take pride.