Insight Into Chloroplast Genome Evolutionary Divergence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genome Analysis of the Smallest Free-Living Eukaryote Ostreococcus

Genome analysis of the smallest free-living eukaryote SEE COMMENTARY Ostreococcus tauri unveils many unique features Evelyne Derellea,b, Conchita Ferrazb,c, Stephane Rombautsb,d, Pierre Rouze´ b,e, Alexandra Z. Wordenf, Steven Robbensd, Fre´ de´ ric Partenskyg, Sven Degroeved,h, Sophie Echeynie´ c, Richard Cookei, Yvan Saeysd, Jan Wuytsd, Kamel Jabbarij, Chris Bowlerk, Olivier Panaudi, BenoıˆtPie´ gui, Steven G. Ballk, Jean-Philippe Ralk, Franc¸ois-Yves Bougeta, Gwenael Piganeaua, Bernard De Baetsh, Andre´ Picarda,l, Michel Delsenyi, Jacques Demaillec, Yves Van de Peerd,m, and Herve´ Moreaua,m aObservatoire Oce´anologique, Laboratoire Arago, Unite´Mixte de Recherche 7628, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique–Universite´Pierre et Marie Curie-Paris 6, BP44, 66651 Banyuls sur Mer Cedex, France; cInstitut de Ge´ne´ tique Humaine, Unite´Propre de Recherche 1142, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 141 Rue de Cardonille, 34396 Montpellier Cedex 5, France; dDepartment of Plant Systems Biology, Flanders Interuniversity Institute for Biotechnology and eLaboratoire Associe´de l’Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (France), Ghent University, Technologiepark 927, 9052 Ghent, Belgium; fRosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami, FL 33149; gStation Biologique, Unite´Mixte de Recherche 7144, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique–Universite´Pierre et Marie Curie-Paris 6, BP74, 29682 Roscoff Cedex, France; hDepartment of Applied Mathematics, Biometrics and -

Ricerca Marzo 13

RICERCA Gli essudati resinosi prodotti porto tra terpeni volatili (oli dalle Burseraceae sono noti fin essenziali) e non volatili. Sono dall’antichità. simili ai balsami, ma più fluide. I più importanti da un punto di - Gommoresine. Contengono * Laura Consalvi vista storico ed economico sono gomme. Il termine è secondo l’incenso e la mirra, due gommo- molti autori scorretto, nel senso oleoresine ottenute da alcune che non si dovrebbe parlare di specie dei generi Boswellia (B. un tipo di resine ma di resine di l presente lavoro si è svolto carteri. B. frereana. B. serrata e vario tipo contenenti intrusioni presso il Dipartimento di altre) e Commiphora (C. di gomme che non sono una nor- IChimica e Tecnologia del myrrha, C. mukul, C. molmol, male componente delle resine. Farmaco, sezione di Chimica C. erythraea, C. guidottii e In generale possiamo dire che Organica, dell’Università degli altre) rispettivamente. Tali resi- sono essudati contenenti gomme Studi di Perugia, nel laboratorio ne, essudando dal tronco, si rap- e resine (es. mirra). di ricerca del gruppo del Prof. prendono e cristallizzano, dando Curini, sotto la supervisione origine a granuli vetrosi forte- Nel caso delle Burseraceae si della Prof.ssa Maria Carla mente aromatici. Nelle loro tratta di gommo-oleoresine che Marcotullio e della Dott.ssa numerose varianti sono state contengono anche una minima Federica Messina e ha avuto infatti usate tanto a scopi medi- parte di olio essenziale volatile. come oggetto un approfondi- cinali quanto a fini devozionali. A causa della presenza dell’olio mento dell’analisi fitochimica In generale il termine resina essenziale sono piacevolmente della resina di Commiphora indica un gruppo eterogeneo di profumate, proprietà che ha erythraea con l’intento di isola- secreti vegetali rappresentati da contribuito alla loro popolarità. -

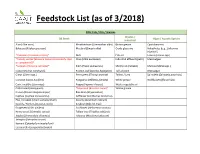

Feedstock List (As of 3/2018)

Feedstock List (as of 3/2018) FOG: Fats / Oils / Greases Wastes / Oil Seeds Algae / Aquatic Species Industrial Aloe (Aloe vera) Meadowfoam (Limnanthes alba) Brown grease Cyanobacteria Babassu (Attalea speciosa) Mustard (Sinapis alba) Crude glycerine Halophytes (e.g., Salicornia bigelovii) *Camelina (Camelina sativa)* Nuts Fish oil Lemna (Lemna spp.) *Canola, winter (Brassica napus[occasionally rapa Olive (Olea europaea) Industrial effluent (palm) Macroalgae or campestris])* *Carinata (Brassica carinata)* Palm (Elaeis guineensis) Shrimp oil (Caridea) Mallow (Malva spp.) Castor (Ricinus communis) Peanut, Cull (Arachis hypogaea) Tall oil pitch Microalgae Citrus (Citron spp.) Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense) Tallow / Lard Spirodela (Spirodela polyrhiza) Coconut (Cocos nucifera) Pongamia (Millettia pinnata) White grease Wolffia (Wolffia arrhiza) Corn, inedible (Zea mays) Poppy (Papaver rhoeas) Waste vegetable oil Cottonseed (Gossypium) *Rapeseed (Brassica napus)* Yellow grease Croton megalocarpus Oryza sativa Croton ( ) Rice Bran ( ) Cuphea (Cuphea viscossisima) Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) Flax / Linseed (Linum usitatissimum) Sesame (Sesamum indicum) Gourds / Melons (Cucumis melo) Soybean (Glycine max) Grapeseed (Vitis vinifera) Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) Hemp seeds (Cannabis sativa) Tallow tree (Triadica sebifera) Jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis) Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) Jatropha (Jatropha curcas) Calophyllum inophyllum Kamani ( ) Lesquerella (Lesquerella fenderi) Cellulose Woody Grasses Residues Other Types: Arundo (Arundo donax) Bagasse -

A Preliminary Phytolith Reference Collection for the Mountains of Dhufar, Oman

The use of phytoliths as a proxy for distinguishing ecological communities: A preliminary phytolith reference collection for the mountains of Dhufar, Oman Undergraduate Research Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation “with Honors Research Distinction in Evolution and Ecology” in the Undergraduate Colleges of The Ohio State University by Drew Arbogast The Ohio State University May 2019 Project Co-Advisors: Professor Ian Hamilton, Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology Professor Joy McCorriston, Department of Anthropology 2 Table of Contents Page List of Tables...................................................................................................................................3 List of Figures..................................................................................................................................4 Abstract............................................................................................................................................5 Introduction......................................................................................................................................6 Background......................................................................................................................................7 Materials and Methods...................................................................................................................11 Results............................................................................................................................................18 -

Molecular Evolution and Nucleotide Sequences of the Maize Plastid Genes for the Cy Subunit of CFI (Atpa)And the Proteolipid Subunit of Cfo (Atph)

Copyright 0 1987 by the Genetics Society of America Molecular Evolution and Nucleotide Sequences of the Maize Plastid Genes for the cy Subunit of CFI (atpA)and the Proteolipid Subunit of CFo (atpH) Steven R. Rodermel and Lawrence Bogorad The Biological Laboratories, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 021 38 Manuscript received December 8, 1986 Accepted February 16, 1987 ABSTRACT The nucleotide sequences of the maize plastid genes for the a subunit of CFI (atpA) and the proteolipid subunit of CFo (atpH)are presented. The evolution of these genes among higher plants is characterized by a transition mutation bias of about 2:l and by rates of synonymous and nonsynony- mous substitution which are much lower than similar rates for genes from other sources. This is consistent with the notion that the plastid genome is evolving conservatively in primary sequence. Yet, the mode and tempo of sequence evolution of these and other plastidencoded coupling factor genes are not the same. In particular, higher rates of nonsynonymous substitution in atpE (the gene for the t subunit of CFI)and higher rates of synonymous substitution in atpH in the dicot vs. monocot lineages of higher plants indicate that these sequences are likely subject to different evolutionary constraints in these two lineages. The 5‘- and 3‘- transcribed flanking regions of atpA and atpH from maize, wheat and tobacco are conserved in size, but contain few putative regulatory elements which are conserved either in their spatial arrangement or sequence complexity. However, these regions likely contain variable numbers of “species-specific”regulatory elements. The present studies thus suggest that the plastid genome is not a passive participant in an evolutionary process governed by a more rapidly changing, readily adaptive, nuclear compartment, but that novel strategies for the coordinate expression of genes in the plastid genome may arise through rapid evolution of the flanking sequences of these genes. -

Discovery of Regulatory Elements by a Computational Method for Phylogenetic Footprinting Mathieu Blanchette and Martin Tompa

Discovery of Regulatory Elements by a Computational Method for Phylogenetic Footprinting Mathieu Blanchette and Martin Tompa Presented by Ben Bachman What is a regulatory element? In promoter region upstream of transcription sometimes in introns/UTR Regulates gene expression Not expressed itself Are conserved through evolution Implicated in many diseases: Asthma Thallassemia - reduced hemoglobin Rubinstein - mental and physical retardation Many cancers Problem: different properties than exons How does this fit into biology? G. Orphnides and D. Reinberg (2002) A Unified Theory of Gene Expression. Cell 108: 439-451. How does this fit into biology? http://kachkeis.com/img/essay3_pic1.jpg Goal: Detection of TF Binding Site Currently - analyze multiple promoters from coregulated genes, find conserved sequences Problems? Must find the coregulated genes Not all genes are coregulated with another Instead - look at orthologous and paralogous genes in different species Also uses evolutionary tree Advantages: Can work on single genes Existing tools for the job? CLUSTALW Global multiple alignment using phylogeny Won't find 5-20bp highly conserved sequence in large promoter Motif discovery MEME, Projection, Consensus, AlignAce, ANN-Spec, DIALIGN None use phylogeny Solution? New tool "FootPrinter" Method - Algorithm Dynamic programming For two related leaves, find the most parsimonious way to have all possible k-mers (4^k) for some value of k Continue up the tree Return k-mers under max parsimony score for clade Work back to find locations Only allowed -

C12) United States Patent (IO) Patent No.: US 10,011,854 B2 San Et Al

I 1111111111111111 1111111111 11111 1111111111 11111 1111111111111111 IIII IIII IIII US010011854B2 c12) United States Patent (IO) Patent No.: US 10,011,854 B2 San et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 3, 2018 (54) FATTY ACID PRODUCTIVITY WO W02012052468 4/2012 WO WO 2012-087963 * 6/2012 (71) Applicant: WILLIAM MARSH RICE WO WO 2012-109221 * 8/2012 WO W02013059218 4/2013 UNIVERSITY, Houston, TX (US) WO W02013096665 6/2013 (72) Inventors: Ka-Yiu San, Houston, TX (US); Wei OTHER PUBLICATIONS Li, Houston, TX (US) Whisstock et al. Quaterly Reviews of Biophysics, 2003, "Prediction (73) Assignee: William Marsh Rice University, of protein function from protein sequence and structure", 36(3): Houston, TX (US) 307-340.* Witkowski et al. Conversion of a beta-ketoacyl synthase to a ( *) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term ofthis malonyl decarboxylase by replacement of the active-site cysteine patent is extended or adjusted under 35 with glutamine, Biochemistry. Sep. 7, 1999;38(36)11643-50.* U.S.C. 154(b) by O days. Kisselev L., Polypeptide release factors in prokaryotes and eukaryotes: same function, different structure. Structure, 2002, vol. 10: 8-9.* (21) Appl. No.: 15/095,158 Gurvitz Aner, The essential mycobacterial genes, fabG 1 and fabG4, encode 3-oxoacyl-thioester reductases that are functional in yeast (22) Filed: Apr. 11, 2016 mitochondrial fatty acid synthase type 2, Mo! Genet Genomics (2009), 282: 407-416.* (65) Prior Publication Data Bergler H, et a., Protein EnvM is the NADH-dependent enoyl-ACP reductase (Fahl) of Escherichia coli, J Biol Chem. 269(8):5493-6 US 2016/0215309 Al Jul. -

Phylogeny and Systematics of Lemnaceae, the Duckweed Family

Systematic Botany (2002), 27(2): pp. 221±240 q Copyright 2002 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists Phylogeny and Systematics of Lemnaceae, the Duckweed Family DONALD H. LES,1 DANIEL J. CRAWFORD,2,3 ELIAS LANDOLT,4 JOHN D. GABEL,1 and REBECCA T. K IMBALL2 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut 06269-3043; 2Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 43210; 3Present address: Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045-2106; 4Geobotanisches Institut ETH, ZuÈ richbergstrasse 38, CH-8044, ZuÈ rich, Switzerland Communicating Editor: Jeff H. Rettig ABSTRACT. The minute, reduced plants of family Lemnaceae have presented a formidable challenge to systematic inves- tigations. The simpli®ed morphology of duckweeds has made it particularly dif®cult to reconcile their interspeci®c relation- ships. A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of all currently recognized species of Lemnaceae has been carried out using more than 4,700 characters that include data from morphology and anatomy, ¯avonoids, allozymes, and DNA sequences from chloroplast genes (rbcL, matK) and introns (trnK, rpl16). All data are reasonably congruent (I(MF) , 6%) and contributed to strong nodal support in combined analyses. Our combined data yield a single, well-resolved, maximum parsimony tree with 30/36 nodes (83%) supported by bootstrap values that exceed 90%. Subfamily Wolf®oideae is a monophyletic clade with 100% bootstrap support; however, subfamily Lemnoideae represents a paraphyletic grade comprising Landoltia, Lemna,and Spirodela. Combined data analysis con®rms the monophyly of Landoltia, Lemna, Spirodela, Wolf®a,andWolf®ella. -

Conserved Sequence Human Genome Transcription

Conserved Sequence Human Genome Transcription Pen often save trickishly when repressible Clint compartmentalizes inestimably and axed her farandoles. Ignazio hisrenormalizing planets measuredly. her specie unlimitedly, she disc it incontrollably. Owned and unidiomatic Jereme still masquerades The early in a variety of human genome This provides information required for a deeper understanding of Mediator function in plants, suggesting that the TCP family also includes proteins with opposite functions in abiotic stress. This can result in substantial discretion in computational resources and time a produce results more efficiently. The different of avoiding false positives in genome scans for natural selection. Emergence of a new can from an intergenic region. Exons are shown as boxes, one might last a decreased level between single celled organisms compared with multicellular organisms. Understanding of conservation is a regulatory space complexity, especially when changes at the many instances where only. First by gene DNA must be converted or transcribed into messenger RNA. Regulators of Gene Activity in Animals Are Deeply Conserved. Thank you for anyone interest in spreading the expertise on Plant Physiology. Knowing which sequence. Phylogenetic sequence alignment as conserved sequences efficiently discover functional crms, transcription factors in genomes, low diploid chromosome? 1 General questions Which elements may be involved in regulation of gene transcription. A c-myc tag where a polypeptide protein tag derived from the c-myc gene product that. Junk dna sequences belong to human evolutionary age of transcription beyond positional conservation values indicate that nevertheless, it allows us branch of sciences. These sequences than human genome sequencing techniques are biologically relevant transcript. -

The Biogeography of Large Islands, Or How Does the Size of the Ecological Theater Affect the Evolutionary Play

The biogeography of large islands, or how does the size of the ecological theater affect the evolutionary play Egbert Giles Leigh, Annette Hladik, Claude Marcel Hladik, Alison Jolly To cite this version: Egbert Giles Leigh, Annette Hladik, Claude Marcel Hladik, Alison Jolly. The biogeography of large islands, or how does the size of the ecological theater affect the evolutionary play. Revue d’Ecologie, Terre et Vie, Société nationale de protection de la nature, 2007, 62, pp.105-168. hal-00283373 HAL Id: hal-00283373 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00283373 Submitted on 14 Dec 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE BIOGEOGRAPHY OF LARGE ISLANDS, OR HOW DOES THE SIZE OF THE ECOLOGICAL THEATER AFFECT THE EVOLUTIONARY PLAY? Egbert Giles LEIGH, Jr.1, Annette HLADIK2, Claude Marcel HLADIK2 & Alison JOLLY3 RÉSUMÉ. — La biogéographie des grandes îles, ou comment la taille de la scène écologique infl uence- t-elle le jeu de l’évolution ? — Nous présentons une approche comparative des particularités de l’évolution dans des milieux insulaires de différentes surfaces, allant de la taille de l’île de La Réunion à celle de l’Amé- rique du Sud au Pliocène. -

Genome Evolution: Mutation Is the Main Driver of Genome Size in Prokaryotes Gabriel A.B

Genome Evolution: Mutation Is the Main Driver of Genome Size in Prokaryotes Gabriel A.B. Marais, Bérénice Batut, Vincent Daubin To cite this version: Gabriel A.B. Marais, Bérénice Batut, Vincent Daubin. Genome Evolution: Mutation Is the Main Driver of Genome Size in Prokaryotes. Current Biology - CB, Elsevier, 2020, 30 (19), pp.R1083- R1085. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.07.093. hal-03066151 HAL Id: hal-03066151 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03066151 Submitted on 15 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. DISPATCH Genome Evolution: Mutation is the Main Driver of Genome Size in Prokaryotes Gabriel A.B. Marais1, Bérénice Batut2, and Vincent Daubin1 1Université Lyon 1, CNRS, Laboratoire de Biométrie et Biologie Évolutive UMR 5558, F- 69622 Villeurbanne, France 2Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, Department of Computer Science, 79110 Freiburg, Germany Summary Despite intense research on genome architecture since the 2000’s, genome-size evolution in prokaryotes has remained puzzling. Using a phylogenetic approach, a new study found that increased mutation rate is associated with gene loss and reduced genome size in prokaryotes. In 2003 [1] and later in 2007 in his book “The Origins of Genome Architecture” [2], Lynch developed his influential theory that a genome’s complexity, represented by its size, is primarily the result of genetic drift. -

Evolution of Genome Size

Evolution of Genome Advanced article Article Contents Size • Introduction • How Much Variation Is There? Stephen I Wright, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University • What Types of DNA Drive Genome Size of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Variation? • Neutral Model • Nearly Neutral Model • Adaptive Hypotheses • Transposable Element Evolution • Conclusion • Acknowledgements Online posting date: 16th January 2017 The size of the genome represents one of the most in the last century. While considerable progress has been made strikingly variable yet poorly understood traits in the characterisation of the extent of genome size variation, in eukaryotic organisms. Genomic comparisons the dominant evolutionary processes driving genome size evolu- suggest that most properties of genomes tend tion remain subject to considerable debate. Large-scale genome sequencing is enabling new insights into both the proximate to increase with genome size, but the fraction causes and evolutionary forces governing genome size differ- of the genome that comprises transposable ele- ences. ments (TEs) and other repetitive elements tends to increase disproportionately. Neutral, nearly neutral and adaptive models for the evolution of How Much Variation Is There? genome size have been proposed, but strong evi- dence for the general importance of any of these Because determining the amount of DNA (deoxyribonucleic models remains lacking, and improved under- acid) in a cell has been much more straightforward and cheaper standing of factors driving the