Tarleton Bates and Evolution of Republican Man on the Pennsylvania Frontier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

THE Whiskey Insurrection of 1794 Long Has Been Regarded As One of the Decisive Events in Early American History

THE WHISKEY INSURRECTION: A RE-EVALUATION By JACOB E. COOKE* THE Whiskey Insurrection of 1794 long has been regarded as one of the decisive events in early American history. But on the question of why it was significant there has been a century and a half of disagreement. Fortunately for the historian, how- ever, there have not been many interpretations; indeed, there have been only two. And, as anyone would guess, these have been the Federalist and the anti-Federalist, the Hamiltonian and the Jeffersonian. It is not the purpose of this paper to describe the fluctuating historical reputations of Jefferson and Hamilton; at one period of time (say, *the Jacksonian era) Jefferson was in the ascendancy; at another time (say, the post-Civil War period) Hamilton crowded Jefferson out of the American historical hall of fame. But for the past half-century and longer, the interpretation that our historians have given to the American past has been predi- cated on a Jeffersonian bias, and the Whiskey Insurrection is no exception. The generally accepted interpretation of the Whiskey Insur- rection reads something like this: In March, 1791, under the prodding of Alexander Hamilton and against the opposition of the Westerners and some Southerners, Congress levied an excise tax on whiskey. This measure was an integral part of Hamilton's financial plan, a plan which was designed to soak the farmer and to spare the rich. There was sporadic opposition to the excise in several parts of the country, but the seat of opposition was in the four western counties of Pennsylvania. -

John Milledge Letter

10/18/2014 John Milledge letter John Milledge letter Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Milledge, John, 1757-1818. Title: John Milledge letter Dates: 1793 Extent: 0.05 cubic feet (1 folder) Identification: MS 1796 Biographical/Historical Note John Milledge, II (1757-1818) was born in Savannah, Georgia, the only son of John Milledge (1721-1781) and Ann (Smith) Milledge. A prominent lawyer, Milledge sided with the patriots and fought in the Revolutionary War, served as Attorney-General of Georgia in 1780, as a member of the Georgia House of Representatives (1782-1790), as a member of the United States Congress (1792-1801), as Governor of Georgia (1802- 1806), and as a United States Senator (1806- 1809). In 1801, Milledge purchased a 633 acre tract of land for $4,000 and named it "Athens" in honor of Greece's ancient center of culture and learning. He was a key figure in the establishment of the University of Georgia. Not only was he on the committee that decided the location of the institution, but he donated the 633 acre tract of land where the university and the city of Athens now stand. The Georgia state legislature called for the establishment of a town to be named after Milledge in 1803 and one year later Milledgeville became Georgia's fourth capital. Milledgville, located in Baldwin County, served as Georgia's state capital from 1804 until 1868. Milledge resigned his Senate seat in 1809 and returned to Georgia to be with his wife, Martha Galphin Milledge, who was very ill and later died. -

Vol. IV of Minutes of the Trustees of the University of Georgia (November 6, 1858 – August 1, 1877) PART I: COVERING YEARS

Vol. IV of Minutes of the Trustees of the University of Georgia (November 6, 1858 – August 1, 1877) PART I: COVERING YEARS 1858 –1871 and PART II: COVERING YEARS 1871 –1877 Vol. IV of Minutes of the Trustees of the University of Georgia (November 6, 1858 – August 1, 1877) PART I: COVERING YEARS 1858 –1871 pages 1- 364 of the original holograph volume or pages 1- 277 of the typed transcribed source put into electronic form by Susan Curtis starting: May 28th, 2010 finished: June 9, 2010 personal notes: 1. Beginning on page 294 whoever was typing the manuscript began using m.s. for misspelled words instead of sic. The problem is sometimes the word was corrected and sometimes not. I retained the (m.s.) designation when the typist corrected the spelling and substituted sic when the text is still misspelled. 2. Beginning on page 294 the typist switched to double spacing the text. I retained the spacing which had been used previously. 3.The words conferred, referred and authorize often were spelled as confered, refered, and authorise respectfully and were left as they appeared (not highlighted). page numbers in this version refer to the page number found in the original holograph minutes (not those of the typed transcription) and are indicated as: (pge 1) Penciled in remarks from the source text are preserved in this edition in parentheses. This may be confused with text which appears to have been entered in parenthesis in the original document. Any changes made by the current transcripting party are in brackets. As with previous volumes begun on Sept. -

O Código De Honra; E Se Sente Envergonhado — Lembre-Se Do Caso De Descartes — Mesmo Que Ninguém Mais Saiba Que Você Falhou

magistris meis et vivis et mortuis Seria uma espécie de impiedade, e quase uma calúnia à natureza humana, crer que existe alguma profissão ou atividade estabelecida e respeitável em que o homem não possa continuar a agir com honestidade e honra; e, analogamente, sem dúvida não existe nenhuma que não possa vez por outra apresentar tentações em contrário. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, 1817 Sumário Prefácio 1. Morre o duelo 2. A libertação dos pés chineses 3. O fim da escravidão atlântica 4. Guerras contra mulheres 5. Lições e legados Agradecimentos e fontes Notas Prefácio Este livro começou com uma questão simples: o que podemos aprender sobre a moral examinando revoluções morais? Fiz essa pergunta porque historiadores e filósofos têm descoberto muito sobre a ciência com o estudo cuidadoso das revoluções científicas. Thomas Kuhn e Paul Feyerabend, por exemplo, chegaram a conclusões fascinantes examinando a Revolução Científica do século xvii — que nos deu Galileu, Copérnico e Newton — e a revolução mais recente que nos trouxe as assombrosas teorias da física quântica. Sem dúvida, o desenvolvimento do saber científico gerou uma explosão tecnológica maciça. Mas o espírito que move a ciência não é transformar o mundo, e sim entendê-lo. A moral, por outro lado — como insistiu Immanuel Kant —, é, em última análise, prática: moralmente, importa o que pensamos e sentimos, mas a moral, em sua essência, está no que fazemos. Portanto, como uma revolução é uma grande mudança em pouco tempo, uma revolução moral tem de incluir uma rápida transformação no comportamento moral, e não só nos sentimentos morais. Ainda assim, ao final da revolução moral, como ao final de uma revolução científica, as coisas parecem novas. -

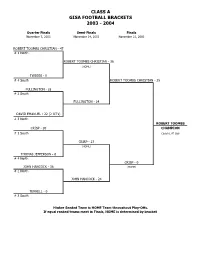

Class a Gisa Football Brackets 2003 - 2004

CLASS A GISA FOOTBALL BRACKETS 2003 - 2004 Quarter Finals Semi-Finals Finals November 7, 2003 November 14, 2003 November 21, 2003 ROBERT TOOMBS CHRISTIAN - 47 # 1 North ROBERT TOOMBS CHRISTIAN - 36 (HOME) TWIGGS - 0 # 4 South ROBERT TOOMBS CHRISTIAN - 35 FULLINGTON - 28 # 2 South FULLINGTON - 24 DAVID EMANUEL - 22 (2 OT's) # 3 North ROBERT TOOMBS CRISP - 20 CHAMPION # 1 South Coach L.M. Guy CRISP - 27 (HOME) THOMAS JEFFERSON - 6 # 4 North CRISP - 0 JOHN HANCOCK - 38 (HOME) # 2 North JOHN HANCOCK - 24 TERRELL - 0 # 3 South Higher Seeded Team is HOME Team throughout Play-Offs. If equal ranked teams meet in Finals, HOME is determined by bracket. 2003 GISA STATE FOOTBALL BRACKETS Friday, Nov. 7 AA BRIARWOOD - 21 Friday, Nov. 14 R1 # 1 Home is team with highest rank; when teams are (1) BRIARWOOD - 15 equally ranked, Home is as shown on brackets. (HOME) WESTWOOD - 0 Friday, Nov. 21 R3 # 4 (9) BRIARWOOD - 14 MONROE - 0 R4 # 2 (2) BULLOCH - 0 BULLOCH - 35 R2 # 3 Friday, Nov. 28 TRINITY CHRISTIAN - 47 R2 # 1 SOUTHWEST GA - 25 (3) TRINITY CHRISTIAN - 17 (13) (Home) (HOME) GATEWOOD - 6 R4 # 4 (10) TRINITY CHRISTIAN - 14 (HOME) BROOKWOOD - 6 R3 # 2 (4) BROOKWOOD - 14 EDMUND BURKE - 14 (15) BRENTWOOD R1 # 3 AA CHAMPS Coach Bert Brown SOUTHWEST GEORGIA - 51 R3 # 1 BRENTWOOD - 52 (5) SOUTHWEST GA - 44 (14) (HOME) CURTIS BAPTIST - 14 R1 # 4 (11) SOUTHWEST GA - 27 TIFTAREA - 42 (HOME) R2 # 2 (6) TIFTAREA - 14 PIEDMONT - 16 R4 # 3 FLINT RIVER - 27 R4 # 1 (7) FLINT RIVER - 21 (HOME) MEMORIAL DAY - 6 R2 # 4 (12) BRENTWOOD - 25 BRENTWOOD - 42 R1 # 2 (8) BRENTWOOD - 46 VALWOOD - 30 R3 # 3 2003 GISA STATE FOOTBALL BRACKETS Friday, Nov. -

Athens Campus

Athens Campus Athens Campus Introduction The University of Georgia is centered around the town of Athens, located approximately 60 miles northeast of the capital of Atlanta, Georgia. The University was incorporated by an act of the General Assembly on January 25, 1785, as the first state-chartered and supported college in the United States. The campus began to take physical form after a 633-acre parcel of land was donated for this purpose in 1801. The university’s first building—Franklin College, now Old College—was completed in 1806. Initially a liberal-arts focused college, University of Georgia remained modest in size and grew slowly during the Figure 48. Emblem of the antebellum years of the nineteenth century. In 1862, passage of the Morrill Act University of Georgia. by Congress would eventually lead to dramatic changes in the focus, curriculum, and educational opportunities afforded at the University of Georgia. The Morrill Act authorized the establishment of a system of land grant colleges, which supported, among other initiatives, agricultural education within the United States. The University of Georgia began to receive federal funds as a land grant college in 1872 and to offer instruction in agriculture and mechanical arts. The role of agricultural education and research has continued to grow ever since, and is now supported by experiment stations, 4-H centers, and marine institutes located throughout the state. The Athens campus forms the heart of the University of Georgia’s educational program. The university is composed of seventeen colleges and schools, some of which include auxiliary divisions that offer teaching, research, and service activities. -

CUMBERLAND Winter 2007 Volume Twenty-Four County History Number Two

CUMBERLAND Winter 2007 Volume Twenty-four County History Number Two In This Issue Richard C. and Paul C. Reed Architectural Collection Kristen Otto Churchtown Perspectives- 1875 Merri Lou Schaumann The Cow Pens janet Taylor A Murder in the James Hamilton House Susan E. Meehan Basket Ball- Carlisle Indians Triumphant john P. Bland Book Review Fear-Segal, White Man's Club: Schools, Race, and the Struggle of Indian Acculturation Reviewed by Cmy C. Collins Notable Acquisitions, Hamilton Library- July through December 2007 Board of Directors Contributions Solicited William A. Duncan, Pres ident The editor invites articles, no res, or docu JeffreyS. Wood, Vice President menrs on rhe history of C umberl and Counry Deborah H. Reitzel, Secretary and irs people. Such articles may deal wirh D avid Goriry, Treasurer new areas of research or m ay review what has been wrirren and published in the pasr. Nancy W Bergen Manuscripts should be typed double Bill Burnerr spaced . Citations should also be double James D. Flower, Jr. George Gardner spaced; rhey should be placed at the end of Georgia Gish rhe texr. Electronic submiss ions should be Homer E . H enschen in Word format wirh any sugges ted graphics Ann K. Hoffer digitized. Linda Mohler Humes Authors should follow the rules set our in Steve Kaufman rhe Chicago Manual ofStyle. Earl R. Kell er Queries concerning the content and form Virginia LaFond Robert Rahal of contributions may be sent ro rhe Editor ar Rev. Mark Scheneman rhe Sociery. Hilary Simpson Membership and Subscription Publications Committee The bas ic annual membership fee of rhe JeffreyS. -

TPS Eastern Region Waynesburg University Barb Kirby, Director

TPS Eastern Region Waynesburg University Barb Kirby, Director Whiskey Rebellion Primary Source Set June 2018 Note: Transcripts for newspaper clippings appear on the page following the image. Click on title to view Primary Source The Excise Tax Excise Tax Act 1791 2 Alexander Hamilton on the Tax 1791 4 Albert Gallatin’s Petition Against the Tax 1792 6 1792 Meeting in Pittsburgh to Protest the Tax 7 The Rebels Protests Raising the Liberty Pole 9 Fort Gaddis Liberty Pole 10 Tarring and Feathering 11 Burning Cabin 12 Tom the Tinker Notice 13 Parkinson’s Ferry Meeting 15 Postal Theft and meeting in Braddock’s Field 17 Counsel Before the Attack at General Neville’s House 19 The Federal Reaction The Terrible Night (Image) 20 The Dreadful Night Text) 21 Washington’s Proclamation 22 Washington Calls Out the Militia 24 U.S. vs Vigol Trial 25 Vegol and Mitchell Sentencing 27 President Washington Pardons Vigol and Mitchell 29 Bradford Wanted Poster 30 President Adams Pardons David Bradford 32 2 Excise Tax 1791 A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 – 1875 1st Congress, 3rd Session p. 199 http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=001/llsl001.db&recNum=322 3 Excise Tax 1791 (continued) A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 – 1875 1st Congress, 3rd Session p. 203 http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=001/llsl001.db&recNum=322 4 Alexander Hamilton And The Whiskey Tax Simon, Steve. Alexander Hamilton and the Whiskey Tax. -

Edward Bates & Lydia Fairbanks

4/18/2021 Bates Place The Wayback Machine - https://web.archive.org/web/20150204163352/http://batesplace.org/ebates.htm Home Bates Branches Edward Bates & Edward Bates & Lydia Fairbanks Lydia Fairbanks Oliver Bates & Edward Bates arrived in Boston from England September 18, 1633 onboard Rebecca Hart the Griffin. On that ship were 100 passengers, including Anne Hutchinson who would play a part in his life. Most on the Griffin were likely followers of Reverend John Cotton who had already made his way to Boston. On the Cyrus Bates & passenger list was the Reverend Jonathan Lothrop who had conducted Lydia Harrington separatist services in Edgerton, Kent and London, and the Rev. Zachariah Symmes of Canterbury, Kent. From The Planters of the Commonwealth by Ormus Ephraim Bates Charles Edward Banks: Arlin Henry Bates & It is a puzzle to imagine what things occupied the time of these Luvena Abigail Adams emigrants for ten weeks on the crowded decks of the small vessels which took them across the three thousand miles that lay between the Lyman Lester Bates & continents. Even to-day with our many permitted diversions time hangs Sarah Edith Lee heavily. Certainly those residents of the rural hamlets left nothing of interest behind them, and so missed nothing in their drab lives when Bulletin Board exchanging their pithless parochial existence ashore for the monotonous doldrums of a swaying deck at sea. Ships carrying Bates Place Bulletin religious groups, like the Mayflower or the Arbella, indulged in daily Board services when their spiritual leaders 'exercised' the Godly in prayer and Other Lines sermon. We can readily believe that Mistress Anne Hutchinson furnished enough excitement aboard the Griffin when she engaged the Tuttle Reverend John Lothrop and the Reverend Zachariah Symmes in by Sam Behling theological bouts, but these were exceptional ships, as the vast majority of emigrants came without ministerial leaders to entertain them. -

The Whiskey Rebellion and a Fractured Early Republic

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 12-2013 A Nation That Wasn't: The Whiskey Rebellion and a Fractured Early Republic Kevin P. Whitaker Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Whitaker, Kevin P., "A Nation That Wasn't: The Whiskey Rebellion and a Fractured Early Republic" (2013). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 345. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NATION THAT WASN'T: THE WHISKEY REBELLION AND A FRACTURED EARLY REPUBLIC by Kevin P. Whitaker A plan-B thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: ________________________ ________________________ Kyle T. Bulthuis Keri Holt Major Professor Committee Member __________________________ James E. Sanders Committee Member UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT 2013 1 Scholars often present nationalism as a cohesive social construction, modeled on Benedict Anderson's theory of imagined communities.1 The strength and popularity of Anderson's immensely useful paradigm of nationalism, however, perhaps leads to excited scholars over-extending his theory or seeing imagined communities that are little more than imaginary. The early Republic forms one such historical time period where, evidence suggests, historians have conjured nationalism where only a fractured nation existed. -

Entire Bulletin

Volume 50 Number 29 Saturday, July 18, 2020 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 3563—3700 Agencies in this issue The Courts Board of Coal Mine Safety Department of Banking and Securities Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Department of Environmental Protection Department of Health Department of Human Services Department of Revenue Department of Transportation Environmental Quality Board Governor’s Office Housing Finance Agency Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Legislative Reference Bureau Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Philadelphia Parking Authority State Board of Nursing Detailed list of contents appears inside. Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporter (Master Transmittal Sheet): Pennsylvania Bulletin Pennsylvania No. 548, July 2020 TYPE OR PRINT LEGIBLY Attn: 800 Church Rd. W. 17055-3198 PA Mechanicsburg, FRY COMMUNICATIONS, INC. COMMUNICATIONS, FRY CUT ON DOTTED LINES AND ENCLOSE IN AN ENVELOPE CHANGE NOTICE/NEW SUBSCRIPTION If information on mailing label is incorrect, please email changes to [email protected] or mail to: mail or [email protected] to changes email please incorrect, is label mailing on information If (City) (State) (Zip Code) label) mailing on name above number digit (6 NUMBER CUSTOMER NAME INDIVIDUAL OF NAME—TITLE OFFICE ADDRESS (Number and Street) (City) (State) (Zip The Pennsylvania Bulletin is published weekly by Fry PENNSYLVANIA BULLETIN Communications, Inc. for the Commonwealth of Pennsylva- nia, Legislative Reference Bureau, 641 Main Capitol Build- (ISSN 0162-2137) ing, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120, under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Docu- ments under 45 Pa.C.S. Part II (relating to publication and effectiveness of Commonwealth documents). The subscrip- tion rate is $87.00 per year, postpaid to points in the United States.