Victorian Brass Bands: the Establishment of a 'Working Class Musical Tradition'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Composer Suggestions for the Euphonium

Euphonium: 3-Valve, 4-Valve, and 4-Valve Compensating Euphoniums: (The low range and intonation will differ depending on how many valves you have) *see attached chart Breath capacity Articulations: staccato, accents, slurred, legato tonguing, no marking Trills and Tremoli Double and Triple Tonguing Extended Techniques: Flutter Tonguing and Multi-phonics Mutes (You MUST allow time to put the mute in and adjust tuning slide) Composer Suggestions: “The euphonium is often called the “cello” of the band or the “shortstop” of a ball team.” Counter Melodies are great! It can be treated as an individual or be combined with the Clarinets, Horns, Saxes and other brasses. Earlier band literature treated it as an a “cello”, but more recent composers and arrangers are often treating it in a “new and lesser” role. They often give it the upper octave of the tuba part or treat it like a 3rd trombone. It has many more capabilities! The Euphoniums role changes depending on what group it is in. (Orchestras, Jazz Combos, Chamber Ensembles, and British Brass Bands) For example, in a British Brass Band it is treated in this way: The euphonium part is flexible and is often compared to that of the `cello in an orchestra. It is equally at home doubling the solo cornet line an octave down, as a melodic or counter-melodic lead, doubling the Bb bass an octave up or occasionally with the 1st trombone. The range of the part is large: most players will be comfortable over more than two octaves, from low G to top A, with the occasional higher note. -

Soprano Cornet

SOPRANO CORNET: THE HIDDEN GEM OF THE TRUMPET FAMILY by YANBIN CHEN (Under the Direction of Brandon Craswell) ABSTRACT The E-flat soprano cornet has served an indispensable role in the British brass band; it is commonly considered to be “the hottest seat in the band.”1 Compared to its popularity in Britain and Europe, the soprano cornet is not as familiar to players in North America or other parts of world. This document aims to offer young players who are interested in playing the soprano cornet in a brass band a more complete view of the instrument through the research of its historical roots, its artistic role in the brass band, important solo repertoire, famous players, approach to the instrument, and equipment choices. The existing written material regarding the soprano cornet is relatively limited in comparison to other instruments in the trumpet family. Research for this document largely relies on established online resources, as well as journals, books about the history of the brass band, and questionnaires completed by famous soprano cornet players, prestigious brass band conductors, and composers. 1 Joseph Parisi, Personal Communication, Email with Yanbin Chen, April 15, 2019. In light of the increased interest in the brass band in North America, especially at the collegiate level, I hope this project will encourage more players to appreciate and experience this hidden gem of the trumpet family. INDEX WORDS: Soprano Cornet, Brass Band, Mouthpiece, NABBA SOPRANO CORNET: THE HIDDEN GEM OF THE TRUMPET FAMILY by YANBIN CHEN Bachelor -

Brass Instruments

Course Content - Brass Instruments Introduction to Brass Instruments • Instruments are considered to belong in the Brass family if they make their sounds because of vibrations from the mouth and a mouthpiece. • Brass instruments are not necessarily made of brass. For example, the Digeridoo is a brass instrument made of wood. • The shape of the tube in a brass instrument is called a bore. The size and shape of the bore creates the sound of the instrument. • There are two shapes of bores: Cylindrical and Conical. • A Cylindrical bore stays the same width from beginning to end. A Conical bore gets wider as it progresses. • The very end of a brass instrument is called the Bell. • The two brass families are the Valved and Slide families. The only instrument in the slide family is the Trombone. • Valves on brass instruments are used to change the note by changing the size or length of the tube. Large and Medium Sized Brass Instruments • The largest instrument in the brass family is the Tuba. It plays the lowest notes. • The Sousaphone was invented to replace the Tuba in a marching band. It is designed to be carried. • Sousaphones are often made of lightweight fiberglass. • One of the oldest brass instruments is the Trombone. The slide of the trombone controls the notes instead of valves. • The French horn is the only brass instrument that is played left-handed. Music in Life Lesson: The Music in Life lesson is a moment to engage in active listening. The Music in Life lesson song for this course is "Flight of the Bumblebee” by Canadian Brass. -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love. -

A, Fl }J)-A?L~---- Dr

A SURVEY OF ACTIVE BRASS BANDS IN THE STATE OF OHIO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Diana Droste Herak, B.M.E. * * * * * The Ohio State University 1999 Master's Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Jon Woods, Adviser Dr. Jere Forsythe __a,_fL_}j)-A?L~---- Dr. Russel Mikkelson v--- Adviser School of Music Copyright by Diana Droste Herak 1999 ABSTRACT In England, many adult amateur musicians continue playing their instruments throughout their lives in the brass band world. In contrast, American adult musicians rarely continue performing once their school days are over. By conducting a survey of the current status of active brass bands in Ohio, it is the intent of this study to offer an historical background of each band, bring more exposure to the brass band movement, and promote brass banding as a musically worthwhile activity for adult amateur musicians. Not much is known about the history and current status of the brass band movement in America. In 1992, Dr. Ned Mark Hosler completed a dissertation entitled “The Brass Band Movement in North America: A Survey of Brass Bands in the United States and Canada.” The intent of this thesis was to focus specifically on British-style brass bands in the state of Ohio. A questionnaire was administered to a sample population of British brass bands in Ohio. The categories covered in the survey included basic information, band origin, membership demographics, instrumentation, organizational structure, rehearsals/performances, public/community support, repertoire, the impact of the North American Brass Band Association, and general considerations. -

Fanfare Cioca Rlia

������ ������������������������ ������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������������� ����������������� ������������������ �������������� �������������� ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������ ���������������������������������������� �������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ���������������������� ������������������������������������������ ������������������ ������������������������������� ������ ��������� ������������������������� ������� �������������� ���������������������� Fanfare Ciocărlia Wednesday, April 13, 2016, 7:30 p.m. �������������������������� ���������������Gartner Auditorium, the Cleveland Museum of Art ������������� ����������������������� ����������������������������������������������������� ������������������ �������������������������������������������������������� PROGRAM �������������������������������������������������������� ������������� ������������ �������������������Toba Mare ������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������� ��������������� �������������������������������������������������������� Sirba Monastirea ���������������������������������������������������� -

The Poetry of Brass Bands

The poetry of brass bands Gavin Holman 28 September 2017 (National Poetry Day) - updated May 2020 Over the years several brass bands have been immortalised in poetry. From those lauding their heroes to the ones which are critical or even insulting. From the earliest days poets have found something in the music of the bands and the people who play in them to inspire their muse. I think it is fair to say that most of the writers would not have made a career out of their works - some are certainly more William McGonagall than William Wordsworth – but nonetheless they are priceless views of the bands and bandsmen. 99 examples of odes to the bands of the past are provided here for your enjoyment. A brass band on contest platform, early 1900s 1 Contents RISHWORTH AND RYBURN VALLEY BRASS BAND ........................................... 4 CAMELON BRASS BAND .................................................................................. 4 SLAIDBURN BAND ........................................................................................... 5 FRECKLETON BAND ......................................................................................... 5 ROTHWELL TEMPERANCE BAND ..................................................................... 5 THOSE CORNETS! (Barrow upon Humber Band)............................................. 6 HARROGATE BAND SONG ............................................................................... 6 WHAT A DAY (Ecclesfield Silver Band) ............................................................ 7 CARNWATH BRASS -

Trombone People Loved It, Because We Were Picking up the Beat' Trombonists in Every Era and Genre - Performers Who (Rogovoy 2001)

Trombone people loved it, because we were picking up the beat' trombonists in every era and genre - performers who (Rogovoy 2001). Players such as the Dirty Dozen Brass have cumulatively expanded the possibilities for trom- Band's Kirk Joseph have amplified the sousaphone to bone range, sound quality capabilities and performance emulate many characteristics of the electric bass guitar. speed in ways completely unanticipated and unimagin- able in European art music. It is here, in the popular Bibliography sphere, that the trombone has made its most expressive Bevan, Clifford. 1978, The Tuba Family. London; Faber impact as an instrument with unique vocal and emo- and Faber, tional qualities. Rogovoy, Seth, 2001, 'Dirty Dozen Updates New Orleans The 'tailgate' trombone style, critical to the sound of Street-Band Music' Berkshire Eagle (30 November), Dixieland collective improvisation, was developed sub- http;//www.rogovoy,com/150.shtml stantially in the second and third decades of the twenti- Schafer, William J. 1977. Brass Bands and New Orleans eth century by Edward 'Kid' Ovf and Jim Robinson. Jack Jazz. Baton Rouge, LA; Louisiana State University Teagarden, Jimmy Harrison, Vic Dickenson, Benny Press, Morton and Dicky Wells extended the melodic and rhythmic capabilities of the trombone in the 1920s and Discography 1930s in the transition to swing. Band leader trombon- Dirty Dozen Brass Band, The, My Feet Can't Fail Me Now. ists like Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey developed the Concord Jazz 43005. 1984: USA, trombone's role as a lyrical lead -

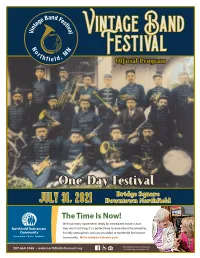

VBF 2021 Program FINAL

n e Ba d Fe ag st t iv in a l V Vintage Band N o N r t M Festival h , f i e l d Official Program One-Day Festival Bridge Square july 31, 2021 Downtown Northfield The Time Is Now! We have many apartments ready for immediate move in, but they won’t last long. It’s a perfect time to learn about the amenities, friendly atmosphere and care provided at Northfield Retirement Community. We’re ready to welcome you! Northfield Retirement Community 507-664-3466 • www.northfieldretirement.org is an Equal Opportunity Provider. Join us the weekend after Labor Day. Sell THE DEFEAT OF your home Jesse james or buy DAYS your next home with the northfield expert LIVING HISTORY! VINTAGE BAND FESTIVAL FAST ACTION! 2021 Stage Sponsor GREAT ENTERTAINMENT! Board Member & Past Chair FUN FOR THE WHOLE FAMILY! Jan StevenS Bank Raid Re-enactments | Music & Entertainment REALTOR | Certified Residential Specialist PRCA Rodeo | Classic Car Show | Carnival Rides Arts & Crafts Fair | Grand Parade | Great Food Antique Tractor Pull | 5k Run/Walk | And Much More! www.jstevens.cbrivervalley.com Sept. 8-12, 2021 [email protected] (507) 244-0500 EVENTS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE | DJJD . ORG Each office is independently owned and operated. ESOTA IINN M T ES AT ITS B E May 22-October 23 September 8-12 October 9 & 10 Riverwalk Market Fair Defeat of Jesse James Days South Central MN Studio ArTour September 3-5 September 11 & 12 December 9 Rice County Steam & Gas Show Riverfront Fine Arts Festival Winter Walk ARTS, HISTORY & OUTDOORS! VISITNORTHFIELD.ORG 2 2021 Vintage Band Festival Program Festival Sponsors Jo Ann Polley & Mark Ulmer elcome to the 2021 Vintage Band Festival! WOn behalf of the entire Vintage Band Festival Board of Directors, I want to welcome you to Northfield, Minnesota, and Vintage Band Festival 2021. -

Brasslands English Dialog List MASTER

BRASSLANDS DIALOG LIST Text: Meerkat Media Collective Presents It is said that time stops when the trumpet festival begins So I'm winding all my clocks now. Text: Guča, Serbia Population 2,200 Text: Brasslands Text: This summer, half a million people will fill this valley for the world's largest trumpet festival. Text: For the 50th anniversary, bands from around the world will come to compete in the first international competition. Text: Brooklyn, New York 4,524 miles from Guča 3'28" Thank you Thank you. Thank you very much. We're Zlatne Uste. Thank you very much. Nobody's Serbian though. Nobody's Serbian, but you guys are so authentic. Thank you, thank you. You made my year, Michael. Still good after all these years! Lower Third: Michael Ginsburg Middle School Gym Teacher Hello, I'm Michael Ginsburg and I am the director of Zlatne Uste, and have been since its beginnings in 1983. "Zlatne Uste," is that a Serbian… It's kind of a pan… it's not correct Serbian… It's grammatically incorrect Serbian. What does it translate to roughly? Well, umm… Golden Lips. Ah, very good. Okie doke. Time to go. Next set. 6'50" That was Demiran's Cocek. And it was named after Demiran Cerimovic the leader of the Pearls of Vranje. This is one of the bands we studied with in Serbia. We play as close to the Serbian style of playing as we can. Lower Third: Emerson Hawley Retired Biomedical Engineer Not that we succeed, but we try as hard as we can to be really hard on attacks and make some parts percussive. -

Instrument Making of the Salvation Army

30 The Galpin Society Journal LXXIII (2020) ARNOLD MYERS Instrument Making of the Salvation Army he Salvation Army was formed as such in contribute to Army events across Britain; in 1880 the September 1878 as a development of the first corps (local congregation) band was established: earlier Christian Mission in the East End of 14 instrumentalists at Northwich.2 The 1880s were a London,T with origins in the Methodist Church, and period of remarkable growth of the Salvation Army became a separate Christian church. It was primarily across Britain (and overseas), and saw brass bands evangelical, and adopted military organisational develop an essential role for the Army in recruitment structures and metaphorical language as an effective and worship. The Salvation Army brass band stratagem. The poor were seen as neglected by the tradition and repertoire have been discussed in depth established churches, and converting the poor to by Boon,3 Herbert,4 Holz5 and Cox,6 allowing us to Christianity was the chief aim of the Salvation Army. focus here on instruments. Conversion was largely brought about by preaching Playing in brass bands was a widely practised the gospel in meetings, and people were attracted pastime for many, so the recruits to the early to meetings by street demonstrations and open- Salvation Army were often already brass band air acts of witness. These demonstrations featured musicians. Some brought their own instruments gospel singing which was usually accompanied by which they then had to sell to the local Army corps: instruments of different kinds. Brass instruments for the others the corps provided instruments which proved to be particularly effective, and the had to be bought from Headquarters. -

British-Style Brass Bands in U.S. Colleges and Universities

BRITISH'STYLE+BRASS+BANDS+IN+U.S.+COLLEGES+AND+UNIVERSITIES+ Mark+Amdahl+Taylor+ + + + Dissertation+Prepared+For+the+DeGree+of+ DOCTOR+OF+MUSICAL+ARTS+ + + + + UNIVERSITY+OF+NORTH+TEXAS+ December+2016+ + + + APPROVED:+ Eugene+Migliaro+Corporon,+Major+Professor+ Dennis+W.+Fisher,+Committee+Member+ Warren+Henry,+Committee+Member+ Benjamin+Brand,+Director+of+Graduate+ Studies+of+the+College+of+Music+ John+Richmond,+Dean+of+the+College+of+ Music+ Victor+Prybutok,+Vice+Provost+of+the+ Toulouse+Graduate+School+ + Taylor, Mark Amdahl. British-Style Brass Bands in U.S. Colleges and Universities. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 2016, 178 pp, 16 tables, 2 figures, references, 55 titles. Since the 1980s, British-style brass bands – community ensembles modeled after the all-brass and percussion bands of Great Britain – have enjoyed a modest regeneration in the United States. The purpose of this research study was: to discover which schools sponsor brass bands currently; to discover which schools formerly sponsored a brass band but have since discontinued it; to describe the operational practices of collegiate brass bands in the U.S.; and to determine what collegiate brass band conductors perceive to be the challenges and benefits of brass band in the curriculum. Data for the study were collected between February, 2015 and February, 2016 using four custom survey instruments distributed to conductors of college and university brass bands. The results showed that 11 American collegiate institutions were sponsoring a brass band during the period of data collection. Results also included the conductors’ reported perceptions that both challenges and benefits are inherent in student brass band participation, and that brass band is a positive experience for students.