On the History and Future of Brass Bands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Composer Suggestions for the Euphonium

Euphonium: 3-Valve, 4-Valve, and 4-Valve Compensating Euphoniums: (The low range and intonation will differ depending on how many valves you have) *see attached chart Breath capacity Articulations: staccato, accents, slurred, legato tonguing, no marking Trills and Tremoli Double and Triple Tonguing Extended Techniques: Flutter Tonguing and Multi-phonics Mutes (You MUST allow time to put the mute in and adjust tuning slide) Composer Suggestions: “The euphonium is often called the “cello” of the band or the “shortstop” of a ball team.” Counter Melodies are great! It can be treated as an individual or be combined with the Clarinets, Horns, Saxes and other brasses. Earlier band literature treated it as an a “cello”, but more recent composers and arrangers are often treating it in a “new and lesser” role. They often give it the upper octave of the tuba part or treat it like a 3rd trombone. It has many more capabilities! The Euphoniums role changes depending on what group it is in. (Orchestras, Jazz Combos, Chamber Ensembles, and British Brass Bands) For example, in a British Brass Band it is treated in this way: The euphonium part is flexible and is often compared to that of the `cello in an orchestra. It is equally at home doubling the solo cornet line an octave down, as a melodic or counter-melodic lead, doubling the Bb bass an octave up or occasionally with the 1st trombone. The range of the part is large: most players will be comfortable over more than two octaves, from low G to top A, with the occasional higher note. -

Soprano Cornet

SOPRANO CORNET: THE HIDDEN GEM OF THE TRUMPET FAMILY by YANBIN CHEN (Under the Direction of Brandon Craswell) ABSTRACT The E-flat soprano cornet has served an indispensable role in the British brass band; it is commonly considered to be “the hottest seat in the band.”1 Compared to its popularity in Britain and Europe, the soprano cornet is not as familiar to players in North America or other parts of world. This document aims to offer young players who are interested in playing the soprano cornet in a brass band a more complete view of the instrument through the research of its historical roots, its artistic role in the brass band, important solo repertoire, famous players, approach to the instrument, and equipment choices. The existing written material regarding the soprano cornet is relatively limited in comparison to other instruments in the trumpet family. Research for this document largely relies on established online resources, as well as journals, books about the history of the brass band, and questionnaires completed by famous soprano cornet players, prestigious brass band conductors, and composers. 1 Joseph Parisi, Personal Communication, Email with Yanbin Chen, April 15, 2019. In light of the increased interest in the brass band in North America, especially at the collegiate level, I hope this project will encourage more players to appreciate and experience this hidden gem of the trumpet family. INDEX WORDS: Soprano Cornet, Brass Band, Mouthpiece, NABBA SOPRANO CORNET: THE HIDDEN GEM OF THE TRUMPET FAMILY by YANBIN CHEN Bachelor -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love. -

Victorian Brass Bands: the Establishment of a 'Working Class Musical Tradition'

HERBERT 1 VICTORIAN BRASS BANDS: THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A 'WORKING CLASS MUSICAL TRADITION' Trevor Herbert y the end of Queen Victoria's reign, brass bands were one of the principal focuses of community music making in the United Kingdom. There were, if we are to believe the optimistic forecasts in one publication, 40,000 of them.1 Such a Bstatistic would indicate that the number of people playing in brass bands by the end of the century was something in the region of 800,000. At about the same time, audience attendance at open air brass band contests was, according to the highest estimate, 160,000 at a single event. This figure was quoted in the popular press following the 1900 National Brass Band Contest at the Crystal Palace. It should not, of course, be taken literally, but it is probably a good indicator of popular impression. When Queen Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837, the term '"brass band" meant nothing more than an ensemble of miscellaneous wind instruments in which brass instruments were prominent. At the end of the century the term was more closely defined. Brass bands had become the raison d'etre for a discrete but significant segment of the British music industry and for a widespread and intricate organizational structure that was largely controlled by working-class people. Since the end of the nineteenth century, the British brass band has had a standard line up of instruments - cornets in Bb (4 'solo', 2 seconds, 2 thirds plus one 'repiano'), 1 soprano cornet in Eb, 1 flugel horn in Bb, 3 tenor saxhorns in Eb, 2 baritone saxhorns in Bb, 2 euphoniums in Bb, 2 Eb basses, 2 BBb basses, 2 tenor trombones, 1 bass trombone, and percussion. -

Das Saxhorn Adolphe Sax’ Blechblasinstrumente Im Kontext Ihrer Zeit

Eugenia Mitroulia/Arnold Myers The Saxhorn Families Introduction The saxhorns, widely used from the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, did not have the same tidy, well-ordered development in Adolphe Sax’s mind and manufacture as the saxophone family appears to have had.1 For a period Sax envisag- ed two families of valved brasswind, the saxhorns and saxotrombas, with wider and narrower proportions respectively. Sax’s production of both instruments included a bell-front wrap and a bell-up wrap. In military use, these were intended for the infantry and the cavalry respectively. Sax’s patent of 1845 made claims for both families and both wraps,2 but introduced an element of confusion by using the term “saxotromba” for the bell-up wrap as well as for the instruments with a narrower bore profile. The confusion in nomenclature continued for a long time, and was exacerbated when Sax (followed by other makers) used the term “saxhorn” for the tenor and baritone members of the nar- rower-bore family in either wrap. The question of the identity of the saxotromba as a family has been answered by one of the present authors,3 who has also addressed the early history of the saxhorns.4 The present article examines the identity of the saxhorns (as they are known today) in greater detail, drawing on a larger sample of extant instruments. In particular, the consistency of Sax’s own production of saxhorns is discussed, as is the question of how close to Sax’s own instruments were those made by other makers. -

A, Fl }J)-A?L~---- Dr

A SURVEY OF ACTIVE BRASS BANDS IN THE STATE OF OHIO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Diana Droste Herak, B.M.E. * * * * * The Ohio State University 1999 Master's Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Jon Woods, Adviser Dr. Jere Forsythe __a,_fL_}j)-A?L~---- Dr. Russel Mikkelson v--- Adviser School of Music Copyright by Diana Droste Herak 1999 ABSTRACT In England, many adult amateur musicians continue playing their instruments throughout their lives in the brass band world. In contrast, American adult musicians rarely continue performing once their school days are over. By conducting a survey of the current status of active brass bands in Ohio, it is the intent of this study to offer an historical background of each band, bring more exposure to the brass band movement, and promote brass banding as a musically worthwhile activity for adult amateur musicians. Not much is known about the history and current status of the brass band movement in America. In 1992, Dr. Ned Mark Hosler completed a dissertation entitled “The Brass Band Movement in North America: A Survey of Brass Bands in the United States and Canada.” The intent of this thesis was to focus specifically on British-style brass bands in the state of Ohio. A questionnaire was administered to a sample population of British brass bands in Ohio. The categories covered in the survey included basic information, band origin, membership demographics, instrumentation, organizational structure, rehearsals/performances, public/community support, repertoire, the impact of the North American Brass Band Association, and general considerations. -

DOI: 156 Reimar Walthert

Reimar Walthert The First Twenty Years of Saxhorn Tutors Subsequent to Adophe Sax’s relocation to Paris in 1842 and his two saxhorn/saxotromba patents of 1843 and 1845, numerous saxhorn tutors were published by different authors. After the contest on the Champ-de-Mars on 22 April 1845 and the decree by the Ministre de la guerre in August 1845 that established the use of saxhorns in French military bands, there was an immediate need for tutors for this new instrument. The Bibliothèque nationaledeFranceownsaround35tutorspublishedbetween1845and1865forthisfamily of instruments. The present article offers a short overview of these early saxhorn tutors and will analyse both their contents and their underlying pedagogical concepts. Early saxhorn tutors in the Bibliothèque nationale de France The whole catalogue of the French national library can now be found online at the library’s website bnf.fr. It has two separate indices that are of relevance for research into saxhorn tutors. Those intended specifically for the saxhorn can be found under the index number “Vm8-o”, whereas cornet tutors are listed under “Vm8-l”. But the second index should not be ignored with regard to saxhorn tutors, because tutors intended for either cornet or saxhorn are listed only here. The most famous publication in thiscategoryisJean-BaptisteArban’sGrande méthode complète de cornet à pistons et de saxhorn. Meanwhile many of these tutors have been digitised and made accessible on the website gallica.fr. Publication periods It is difficult to date the saxhorn tutors in question. On one hand thereisthestampoftheBibliothèquenationaledeFrance,whichcannotalwaysberelied upon. On the other hand, it is possible to date some publications by means of the plate number engraved by the editor. -

President's Message and News of the Field

253 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Jeffrey Nussbaum The HBS has continued to make great progress. Our success is quite evident by the praise that we received from other music organizations at the meeting of early- music societies at the Berkeley Early Music Festival. We have once again exceeded our previous years membership. Our paid 1992 membership is near 550. The HBS Journal is gaining an international reputation as a distinguished publication of world-class caliber. With the HBS Newsletter and the HBS Journal our Society has created an important voice in the music community. We have continued to search for the widest range of articles on early brass, including historical, scientific, biographical topics, and our series of translations of important early treatises, methods and articles. The HBSNL gives us interesting articles, interviews, reviews, and the extensive News of the Field section. In the report given in this issue on the 8th Annual Early Brass Festival, it is noted that we had over 80 people in attendance. It was not only the best Festival yet, but also the largest. I think that it is in large part because of the great interest that the HBS has sparked in the early brass field, that so many people attended EBF 8. Plans are still underway to present a large International Historic Brass Symposium in 1994 or 1995. We now plan to expand the Early Brass Festival at Amherst College for this event. It is hoped that all of the major performers, scholars, collectors, and instrument makers will be invited. Members will be informed as this event develops. -

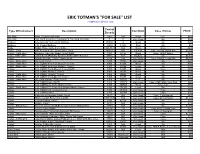

ERIC TOTMAN's "FOR SALE" LIST [email protected]

ERIC TOTMAN'S "FOR SALE" LIST [email protected] Year or Type Of Instrument Description Condition Case / Extras PRICE Decade Alto Horn Henri Pouisson Alto Horn 1900? N/A Good Case $150 Alto Horn York Band Instrument Company Eb ToneKing Alto Horn 0 0 Very Good No $150 Baritone Lyon & Healy "Beau Ideal" Baritone 1890's? 0 Good No $250 Baritone J.W. Pepper Baritone 1880's 14207 Poor No $50 Bugle Rudall, Rose, Carte & Co. Bugle 1858-1871 N/A Good Case $200 Cornet - Echo Ball, Beavon & Cie.. Echo Cornet Outfit 1890?'s N/A Exellent Case, A & Bb Tuning Bits $2,000 Cornet - Parts Horn Buescher TrueTone Model Cornet Outfit 1921 88145 Good Case, HP/LP Slides $200 Cornet TARV OTS John Church (Probably Stratton) TARV OTS Eb Cornet 1870's N/A Exellent No $6,500 Cornet CONN DUPONT "4 IN 1" Cornet Outfit 1878 545 Very Good Case, C/Bb/A Tuning Bits $4,500 Cornet - Parts Horn CG Conn Cornet 1895 30783 Very Good No $200 Cornet - Parts Horn C.G. CONN "New York Wonder" Cornet 1900 64236 Good No $150 Cornet - Parts Horn C.G. CONN "New York Wonder" Cornet 1901 68284 Good No $150 Cornet C.G. CONN "Conn-Queror" Cornet Outfit 1903 81223 Good Case $200 Cornet C.G. CONN "Wonder" Cornet 1905 90190 Good No $200 Cornet - Parts Horn C.G. CONN "Wonder" Cornet 1905 90285 Good No $100 Cornet - Parts Horn C.G. CONN "Conn-Queror" Cornet 1905 91297 Good No $150 Cornet - Parts Horn CG Conn Wonder Phone Cornet 1909 115222 Fair No $150 Cornet C.G. -

VBF 2021 Program FINAL

n e Ba d Fe ag st t iv in a l V Vintage Band N o N r t M Festival h , f i e l d Official Program One-Day Festival Bridge Square july 31, 2021 Downtown Northfield The Time Is Now! We have many apartments ready for immediate move in, but they won’t last long. It’s a perfect time to learn about the amenities, friendly atmosphere and care provided at Northfield Retirement Community. We’re ready to welcome you! Northfield Retirement Community 507-664-3466 • www.northfieldretirement.org is an Equal Opportunity Provider. Join us the weekend after Labor Day. Sell THE DEFEAT OF your home Jesse james or buy DAYS your next home with the northfield expert LIVING HISTORY! VINTAGE BAND FESTIVAL FAST ACTION! 2021 Stage Sponsor GREAT ENTERTAINMENT! Board Member & Past Chair FUN FOR THE WHOLE FAMILY! Jan StevenS Bank Raid Re-enactments | Music & Entertainment REALTOR | Certified Residential Specialist PRCA Rodeo | Classic Car Show | Carnival Rides Arts & Crafts Fair | Grand Parade | Great Food Antique Tractor Pull | 5k Run/Walk | And Much More! www.jstevens.cbrivervalley.com Sept. 8-12, 2021 [email protected] (507) 244-0500 EVENTS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE | DJJD . ORG Each office is independently owned and operated. ESOTA IINN M T ES AT ITS B E May 22-October 23 September 8-12 October 9 & 10 Riverwalk Market Fair Defeat of Jesse James Days South Central MN Studio ArTour September 3-5 September 11 & 12 December 9 Rice County Steam & Gas Show Riverfront Fine Arts Festival Winter Walk ARTS, HISTORY & OUTDOORS! VISITNORTHFIELD.ORG 2 2021 Vintage Band Festival Program Festival Sponsors Jo Ann Polley & Mark Ulmer elcome to the 2021 Vintage Band Festival! WOn behalf of the entire Vintage Band Festival Board of Directors, I want to welcome you to Northfield, Minnesota, and Vintage Band Festival 2021. -

Sound Sets in Sibelius 2

Sound sets in Sibelius 2 For advanced users only! Before attempting to create your own sound set, it is worth checking if one is already available: see the online Help Center at http://www.sibelius.com/helpcenter/resources/ for the latest additions. Disclaimer Sound sets are complex files and are not designed to be user-editable. Using a sound set with incorrect syntax may cause your copy of Sibelius to behave unpredictably or even crash. Sibelius Software accepts no responsibility for any loss of data or other problems experienced as a result of editing the supplied sound sets or creating new ones. This document is provided ‘as is’, and no warranty, implied or otherwise, covers the information contained within. Please also note that we do not offer technical support on the editing or creation of sound set files. Filenames The filename of a sound set file is insignificant (i.e. it is not shown in the Play Z Devices dialog), but we recommend that it should be fairly descriptive. It should also be 31 characters or less (including the .txt file extension) to ensure compatibility with all file systems. Sound set syntax Please refer to the General MIDI.txt file inside C:\Program Files\Sibelius Software\Sibelius 2\Sounds for an example of correct sound set syntax. In fact, you may wish to copy this file and use it as the basis of your own sound set. The sound set starts with an open brace { and ends with a closing brace }. The body of the sound set contains the following fields within the opening and closing braces as a series of ‘tree nodes’, in this order: MIDIDevice Syntax: MIDIDevice "GM (General MIDI)" The name of the device, e.g. -

Tenor Horn Diploma Repertoire List

TENOR HORN DIPLOMA REPERTOIRE LIST January 2021 edition (updated May 2021) • Candidates should compile and perform a programme displaying a range of moods, styles and tempi. • Programmes must consist of a minimum of two works. • All works should be performed complete, except where single movements are specified. • The music performed can: – be drawn entirely from the appropriate repertoire list below – combine pieces from the appropriate repertoire list with own-choice pieces* – contain only own-choice pieces* * Any programme which includes own-choice repertoire must be pre-approved. • Own-choice pieces must demonstrate a level of technical and musical demand comparable to the pieces listed in the relevant repertoire list. • Timings are as follows: Diploma Performance Exam level duration duration ATCL 32-38 minutes 40 minutes LTCL 37-43 minutes 45 minutes FTCL 42-48 minutes 50 minutes • Candidates must provide a written programme and copies of all pieces to be performed. • Face-to-face exams: the appointment form, written programme, copies of the pieces and approval letter (if applicable) should be given to the examiner at the start of the exam. • Digital exams: the submission information form, written programme, scans of the pieces and approval letter (if applicable) should be uploaded with the video. • For full details, including the process for submitting own-choice repertoire, please see the current syllabus at trinitycollege.com/performance-diplomas (face-to-face exams) or trinitycollege.com/digital-music-diplomas (digital exams). ATCL 1. Butterworth Saxhorn Sonata, 3rd movt (E♭ horn edition) Comus Chopin, Nocturne 2. Kirklees arr. Bates (from Jonathan Bates Tenor Horn Solo Album 1) 3.