Gog and Magog Iranian Studies Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Gog and Magog” Revelation 20:7-10; Ezekiel 38 & 39

The Revelation of Jesus Christ “Gog and Magog” Revelation 20:7-10; Ezekiel 38 & 39 Introduction Revelation 20:1-6 presents the reality of Jesus Christ reigning over all the earth for 1000 years while Satan is locked up in the Abyss. In Revelation 20:7-10, John records the vision where Satan is released from the Abyss at the end of the Millennial Reign of Christ. Satan is then able to gather an army of rebels from all nations (“Gog and Magog”) to come against Christ in Jerusalem. This battle is referred to as the “Battle of Gog and Magog”. But there is also a battle of “Gog and Magog” mentioned in Ezekiel 38 & 39. Are these two battles the same? The Scripture makes it clear that there are two separate battles which carry the reference to “Gog and Magog”. Consideration of these battles will powerfully demonstrate that sinful men continue in their sinful rebellion against God, even after His glorious 1000-year reign of peace and prosperity. It is not surprising that God will judge those who reject His salvation through Jesus. I. The Historical Roots of Gog and Magog Gen. 10:2; Ez. 38:2,15; 39:3-9 A. Magog was a grandson of Noah (Genesis 10:2) B. The descendants of Magog settled in Europe and northern Asia (Ez. 38:2) referred to as "northern barbarians" C. The people of Magog were skilled warriors (Ezekiel 38:15; 39:3-9) II. Two Separate Battles of Gog and Magog Ez. 38 & 39; Rev. 20:7-10 A. -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism

Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review 51 | 2016 Global History, East Africa and The Classical Traditions Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism Phiroze Vasunia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/314 Publisher IFRA - Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2016 Number of pages: 21-43 ISSN: 2071-7245 Electronic reference Phiroze Vasunia, « Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism », Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review [Online], 51 | 2016, Online since 07 May 2019, connection on 08 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/314 Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review Global History, East Africa and the Classical Traditions. Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism Phiroze Vasunia Can the Ethiopian change his skinne? or the leopard his spots? Jeremiah 13.23, in the King James Version (1611) May a man of Inde chaunge his skinne, and the cat of the mountayne her spottes? Jeremiah 13.23, in the Bishops’ Bible (1568) I once encountered in Sicily an interesting parallel to the ancient confusion between Indians and Ethiopians, between east and south. A colleague and I had spent some pleasant moments with the local custodian of an archaeological site. Finally the Sicilian’s curiosity prompted him to inquire of me “Are you Chinese?” Frank M. Snowden, Blacks in Antiquity (1970) The ancient confusion between Ethiopia and India persists into the late European Enlightenment. Instances of the confusion can be found in the writings of distinguished Orientalists such as William Jones and also of a number of other Europeans now less well known and less highly regarded. -

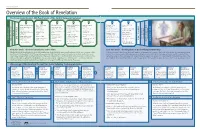

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

The Sixteen Grandsons of Noah (H. Hunt with R

The Sixteen Grandsons of Noah (H. Hunt with R. Grigg) Secular history gives much evidence to show that the survivors of Noah’s Flood were real historical figures, whose names were indelibly carved on much of the ancient world… When Noah and his family stepped out of the Ark, they were the only people on Earth. It fell to Noah’s three sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth, and their wives, to repopulate the earth through the children that were born to them after the Flood. Of Noah’s grandchildren, 16 grandsons are named in Genesis chapter 10. God has left us ample evidence to confirm that these 16 grandsons of Noah really lived, that the names the Bible gives were their exact names, and that after the Babel dispersion (Genesis 11) their descendants fanned out over the earth and established the various nations of the ancient world. The first generations after the Flood lived to be very old, with some men outliving their children, grandchildren, and great- grandchildren. This set them apart. The 16 grandsons of Noah were the heads of their family clans, which became large populations in their respective areas. Several things happened: a) Various areas called themselves by the name of the man who was their common ancestor. b) They called their land, and often their major city and major river, by his name. c) Sometimes the various nations fell off into ancestor worship. When this happened, it was natural for them to name their god after the man who was ancestor of all of them, or to claim their long-living ancestor as their god. -

UNIT 11 the ARABS: INVASIONS and Emergence of Rashtrakutas EXPANSION*

UNIT 11 THE ARABS: INVASIONS AND Emergence of Rashtrakutas EXPANSION* Structure 11.0 Objectives 11.1 Introduction 11.2 The Rise and Spread of Islam in 7th-8th Centuries 11.3 The ChachNama 11.4 The Conquest of Sindh 11.5 Arab Administration 11.6 Arab Conquest of Sindh: A Triumph without Results? 11.7 Summary 11.8 Key Words 11.9 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 11.10 Suggested Readings 11.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this Unit, you will know: the background for understanding the foreign invasions from Arabia in early medieval period; the sources on the Arab conquest of Sindh; the reasons for the capture of Sindh by the Arabs; the phases of conquest of Sindh; the colonial understanding of Sindh conquest; and cultural comingling between the Arab and Indian cultures. 11.1 INTRODUCTION In the Units so far, we had studied about the social, political, economic or cultural aspects of Ancient India. Based on the unique traits of the period, historians have called it as Ancient history. Similarly, the period that followed had its own characteristic features to be termed as Medieval. The rise of Islam in west Asia and the Muslim conquests around the world is atypical of the early medieval period. In this Unit, we will study one such inter-related development in the Indian subcontinent. This is the Arab conquest of Sindh in the north- western region of the subcontinent. The Early Medieval in Indian History The Early Medieval is a phase of transition from ancient to medieval period. In relation to north India, the period before the sultanate phase is termed as early medieval. -

Gog and Magog Battle Israel

ISRAEL IN PROPHECY LESSON 5 GOG AND MAGOG BATTLE ISRAEL The “latter days” battle against Israel described in Ezekiel is applied by dispensationalists to a coming battle against the modern nation of Israel in Palestine. The majority of popular Bible commentators try to map out this battle and even name nations that will take part in it. In this lesson you will see that this prophecy in Ezekiel chapters 36 and 37 does not apply to the modern nation of Israel at all. You will study how the book of Revelation gives us insights into how this prophecy will be applied to God’s people, spiritual Israel (the church) in the last days. You will also see a clear parallel between the events described in Ezekiel’s prophecy and John’s description of the seven last plagues in Revelation. This prophecy of Ezekiel gives you another opportunity to learn how the “Three Fold Application” applies to Old Testament prophecy. This lesson lays out how Ezekiel’s prophecy was originally given to the literal nation of Israel at the time of the Babylonian captivity, and would have met a victorious fulfillment if they had remained faithful to God and accepted their Messiah, Jesus Christ. However, because of Israel’s failure this prophecy is being fulfilled today to “spiritual Israel”, the church in a worldwide setting. The battle in Ezekiel describes Satan’s last efforts to destroy God’s remnant people. It will intensify as we near the second coming of Christ. Ezekiel’s battle will culminate and reach it’s “literal worldwide in glory” fulfillment at the end of the 1000 years as described in Revelation chapter 20. -

Chapter Fourteen Rabbinic and Other Judaisms, from 70 to Ca

Chapter Fourteen Rabbinic and Other Judaisms, from 70 to ca. 250 The war of 66-70 was as much a turning point for Judaism as it was for Christianity. In the aftermath of the war and the destruction of the Jerusalem temple Judaeans went in several religious directions. In the long run, the most significant by far was the movement toward rabbinic Judaism, on which the source-material is vast but narrow and of dubious reliability. Other than the Mishnah, Tosefta and three midrashim, almost all rabbinic sources were written no earlier than the fifth century (and many of them much later), long after the events discussed in this chapter. Our information on non-rabbinic Judaism in the centuries immediately following the destruction of the temple is scanty: here we must depend especially on archaeology, because textual traditions are almost totally lacking. This is especially regrettable when we recognize that two non-rabbinic traditions of Judaism were very widespread at the time. Through at least the fourth century the Hellenistic Diaspora and the non-rabbinic Aramaic Diaspora each seem to have included several million Judaeans. Also of interest, although they were a tiny community, are Jewish Gnostics of the late first and second centuries. The end of the Jerusalem temple meant also the end of the Sadducees, for whom the worship of Adonai had been limited to sacrifices at the temple. The great crowds of pilgrims who traditionally came to the city for the feasts of Passover, Weeks and Tabernacles were no longer to be seen, and the temple tax from the Diaspora that had previously poured into Jerusalem was now diverted to the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus in Rome. -

Migrant Sufis and Shrines: a Microcosm of Islam Inthe Tribal Structure of Mianwali District

IJASOS- International E-Journal of Advances in Social Sciences, Vol.II, Issue 4, April 2016 MIGRANT SUFIS AND SHRINES: A MICROCOSM OF ISLAM INTHE TRIBAL STRUCTURE OF MIANWALI DISTRICT Saadia Sumbal Asst. Prof. Forman Christian College University Lahore, Pakistan, [email protected] Abstract This paper discusses the relationship between sufis and local tribal and kinship structures in the last half of eighteenth century to the end of nineteenth century Mianwali, a district in the south-west of Punjab. The study shows how tribal identities and local forms of religious organizations were closely associated. Attention is paid to the conditions in society which grounded the power of sufi and shrine in heterodox beliefs regarding saint‟s ability of intercession between man and God. Sufi‟s role as mediator between tribes is discussed in the context of changed social and economic structures. Their role as mediator was essentially depended on their genealogical link with the migrants. This shows how tribal genealogy was given precedence over religiously based meta-genealogy of the sufi-order. The focus is also on politics shaped by ideology of British imperial state which created sufis as intermediary rural elite. The intrusion of state power in sufi institutions through land grants brought sufis into more formal relations with the government as well as the general population. The state patronage reinforced their social authority and personal wealth and became invested with the authority of colonial state. Using hagiographical sources, factors which integrated pir and disciples in a spiritual bond are also discussed. This relationship is discussed in two main contexts, one the hyper-corporeality of pir, which includes his power and ability to move through time and space and multilocate himself to protect his disciples. -

Irreverent Persia

Irreverent Persia IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES Poetry expressing criticism of social, political and cultural life is a vital integral part of IRREVERENT PERSIA Persian literary history. Its principal genres – invective, satire and burlesque – have been INVECTIVE, SATIRICAL AND BURLESQUE POETRY very popular with authors in every age. Despite the rich uninterrupted tradition, such texts FROM THE ORIGINS TO THE TIMURID PERIOD have been little studied and rarely translated. Their irreverent tones range from subtle (10TH TO 15TH CENTURIES) irony to crude direct insults, at times involving the use of outrageous and obscene terms. This anthology includes both major and minor poets from the origins of Persian poetry RICCARDO ZIPOLI (10th century) up to the age of Jâmi (15th century), traditionally considered the last great classical Persian poet. In addition to their historical and linguistic interest, many of these poems deserve to be read for their technical and aesthetic accomplishments, setting them among the masterpieces of Persian literature. Riccardo Zipoli is professor of Persian Language and Literature at Ca’ Foscari University, Venice, where he also teaches Conceiving and Producing Photography. The western cliché about Persian poetry is that it deals with roses, nightingales, wine, hyperbolic love-longing, an awareness of the transience of our existence, and a delicate appreciation of life’s fleeting pleasures. And so a great deal of it does. But there is another side to Persian verse, one that is satirical, sardonic, often obscene, one that delights in ad hominem invective and no-holds barred diatribes. Perhaps surprisingly enough for the uninitiated reader it is frequently the same poets who write both kinds of verse. -

A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 237–51 A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MILLENNIUM IN REV 20:1–6: CONSUMMATION AND RECAPITULATION dave mathewson* i. introduction The question of the so-called millennial kingdom in Rev 20:1–6 continues to be a source of fascination in evangelical discussion and dialogue.1 The purpose of this article is to re-examine the question of the millennial king- dom as articulated in Rev 20:1–6. More specifically, this article will consider the meaning and function of 20:1–6 within Revelation as it relates to the contemporary debate about whether this section is best understood within a premillennial or amillennial framework. Hermeneutically, most of the de- bate has centered around how literally the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 should be taken and, more importantly, the relationship be- tween 20:1–6 and 19:11–21. Does the thousand year period in 20:1–6 re- fer to a more or less literal period of time?2 Or should it be understood more symbolically? Does 20:1–6 follow 19:11–21 chronologically, with the one thou- sand years featuring a Zwischenreich (premillennialism), or does the final battle in 20:7–10 recapitulate the battle in 19:11–21, with the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 extending all the way back to the first coming of Christ (amillennialism)?3 * Dave Mathewson is instructor in New Testament at Oak Hills Christian College, 1600 Oak Hills Road SW, Bemidji, MN 56601. 1 Cf. R. -

The International Socialist Review 491

FEBRUARY, 1911 2656 PRICE TEN CENTS INTERNATIONAL ,1 SOCLALISHREVIEW __ , p', k _ .. THE PASSING OF SKILLED LABOR AND CRAFT UNIONS h THE COMING OF INDUSTRIAL SOCIALISM FEBRUARY, 1911 ~£e PRICE TEN CENTS INTERNATIONAL SOCIALIST REVIEW. THE PASSING OF SKILLED LABOR AND CRAFT UNIONS THE COMING OF INDUSTRIAL SOCIALISM ,.fHE INTERNATIONAL SOCIALIST REVIEW OF, B y AND F 0 R T H E WORKING C L A S S EDITED BY CHARLES H. KERR ASSOCIATE EDITORS: Mary E. Marcy, Robert Rives LaMonte, Max S. Hayes, William E.. Bohn, Leslie H. Marcy CONTENTS The Passing of the Glass Blower 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Robert J. Wheeler Pick and Shovel Pointers l The Fighting Welsh Miners ) ... 0 •••• 0 •• 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 •••••••••••• William D. Haywood The Crime of Craft Unionism .. 0. 0 0 0 0 0 ••• 0 0. 0. 0 ••••• 0 0 •••••••••••• • Eugene V. Debs Liberty ...... 0 0. 0 0 ••• 0. 0 0 ••• 0 •••••••••• 0 •• 0 0 0 0 0 0 •••• 0 •••• 0 •• 0 0 •••• Tom J. Lewis Banishing Skill from the Foundry. 0 0 •••••• 0. 0 •••• 0 ••••••••••••• Thomas F. Kennedy The Reign of Terror in Tampa .. 0 •• 0 •••• 0 0 •• 0 0 0 0 0 •••••• 0 •• 0 •• • New York Daily Call Be Your Own Boss .. 0 0 0 0. 0. 0 0 0 •••••••••••• 0 •• 0 ••••••••• 0 ••••••••••• .Jack Morton The Japanese Miners. 0 0 0 • 0 0 • 0 0 0 • 0 • 0 •••••••••••• 0 •••••••• 0 ••• 0 •••• 0 ••• S.