Ariadna Culpan No Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multimedia Systems DCAP303

Multimedia Systems DCAP303 MULTIMEDIA SYSTEMS Copyright © 2013 Rajneesh Agrawal All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara CONTENTS Unit 1: Multimedia 1 Unit 2: Text 15 Unit 3: Sound 38 Unit 4: Image 60 Unit 5: Video 102 Unit 6: Hardware 130 Unit 7: Multimedia Software Tools 165 Unit 8: Fundamental of Animations 178 Unit 9: Working with Animation 197 Unit 10: 3D Modelling and Animation Tools 213 Unit 11: Compression 233 Unit 12: Image Format 247 Unit 13: Multimedia Tools for WWW 266 Unit 14: Designing for World Wide Web 279 SYLLABUS Multimedia Systems Objectives: To impart the skills needed to develop multimedia applications. Students will learn: z how to combine different media on a web application, z various audio and video formats, z multimedia software tools that helps in developing multimedia application. Sr. No. Topics 1. Multimedia: Meaning and its usage, Stages of a Multimedia Project & Multimedia Skills required in a team 2. Text: Fonts & Faces, Using Text in Multimedia, Font Editing & Design Tools, Hypermedia & Hypertext. 3. Sound: Multimedia System Sounds, Digital Audio, MIDI Audio, Audio File Formats, MIDI vs Digital Audio, Audio CD Playback. Audio Recording. Voice Recognition & Response. 4. Images: Still Images – Bitmaps, Vector Drawing, 3D Drawing & rendering, Natural Light & Colors, Computerized Colors, Color Palletes, Image File Formats, Macintosh & Windows Formats, Cross – Platform format. 5. Animation: Principle of Animations. Animation Techniques, Animation File Formats. 6. Video: How Video Works, Broadcast Video Standards: NTSC, PAL, SECAM, ATSC DTV, Analog Video, Digital Video, Digital Video Standards – ATSC, DVB, ISDB, Video recording & Shooting Videos, Video Editing, Optimizing Video files for CD-ROM, Digital display standards. -

Art and Science: Seen As Dichotomous Practiced As Dependent Hannah Green

Art and Science: Seen as Dichotomous Practiced as Dependent Hannah Green Department of Art & Art History Honors Thesis University of Colorado at Boulder April 7, 2014 Thesis Advisor Melanie Walker | Art & Art History Committee Members Shu-Ling Chen Berggreen | Journalism & Mass Communication Françoise Duressé | Art & Art History 1 Abstract: Art and science have an undeniable connection. Many artists and scientists work with or in both fields, however, public discourse and educational structure has created the notion that the subjects are completely disparate. Art and science are divided in classes, majors, and degrees. Furthermore, science is typically required from elementary to collegiate levels of academia, whereas art is optional. Both fields, however, work through creativity by analyzing and critiquing the world. In my thesis work, Death Becomes Us, I have collected flora and fauna, which I later scanned on high-resolution scanners. The resulting large-scale prints (24” wide) reveal complexities of the specimens that evade 20/20 eyesight. The bees and flowers are all dead thus indicating the major colony collapse of pollinators that play a fundamental role in the world from ecology to economy. My work treads the line between the subjects of art and science and aims to bridge the divide that the public sees in the subjects by appealing to both fields, conceptually and aesthetically. By looking at artists and scientists it is clear that the separation that has occurred comes from a change that needs to take place from the bottom up. In other words, art and science need to be integrated in order to eliminate the hierarchy that has become mainstream thought. -

Art and Science: Seen As Dichotomous Practiced As Dependent Hannah Green University of Colorado Boulder

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CU Scholar Institutional Repository University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2014 Art and Science: Seen as Dichotomous Practiced as Dependent Hannah Green University of Colorado Boulder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/honr_theses Recommended Citation Green, Hannah, "Art and Science: Seen as Dichotomous Practiced as Dependent" (2014). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 107. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Honors Program at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Art and Science: Seen as Dichotomous Practiced as Dependent Hannah Green Department of Art & Art History Honors Thesis University of Colorado at Boulder April 7, 2014 Thesis Advisor Melanie Walker | Art & Art History Committee Members Shu-Ling Chen Berggreen | Journalism & Mass Communication Françoise Duressé | Art & Art History 1 Abstract: Art and science have an undeniable connection. Many artists and scientists work with or in both fields, however, public discourse and educational structure has created the notion that the subjects are completely disparate. Art and science are divided in classes, majors, and degrees. Furthermore, science is typically required from elementary to collegiate levels of academia, whereas art is optional. Both fields, however, work through creativity by analyzing and critiquing the world. In my thesis work, Death Becomes Us, I have collected flora and fauna, which I later scanned on high-resolution scanners. -

PDF-Photon | Icon

Photon | Icon darktaxa-project.net Artists: Banz+Bowinkel, Arno Beck, Group-Exhibition, Galerie Falko Alexander, Alex Grein, Beate Gütschow, Florian Kuhlmann, 4.-31.5.2019, Cologne, Curated by Falko Alexander Achim Mohné, Susan Morris, Michael Reisch, and Michael Reisch Ria Patricia Röder, Roland Schappert Photon | Icon jeweiligen Produktionsprozesse steht bei allen beteiligten KünstlerInnen aber eine Entscheidung für ein physikalisch existentes „Bildobjekt“ mit Unter zeitgenössischen digitalen Bedingungen ist derzeit völlig unklar, was mit Körper, Masse und Ausdehnung im realen (Ausstellungs-) Raum als finale dem Begriff „Fotografie“ (sowohl im künstlerischen, als auch im allgemeinen Erscheinungsform der Arbeit. Das „Bild“ wird als substanzielle, faktische und Gebrauch) eigentlich gemeint ist, bzw. ob und wie man dieses Feld sinnvoll materiale Erscheinung thematisiert, dem im Digitalen virulenten Thema der definieren soll. Auflösung und Immersion wird mit einem Gegenkonzept, einer eindeutigen Diese Frage stellt sich vehement im Hinblick auf die neuen digitalen Entscheidung für den realen Raum (Erfahrungsraum) begegnet. Möglichkeiten und Anwendungen. Die Ausstellung Photon | Icon bringt nun in In dem Dreiecksverhältnis Realität - Virtualität - Digitalität wird die Frage einer Art offenen Versuchsanordnung Arbeiten von KünstlerInnen zusammen, gestellt, inwieweit das „Fotografische“ als normative Kraft nicht nur für die mit Digitaler Fotografie, CGI, Photogrammetrie, Scanografie, Augmented die neuen Arbeitsweisen und digitalen Werkzeuge, -

Download Exhibition Catalogue

Sensations of Art-making: Triumphs, Torments and Risk-taking Sensations of Art-making: Triumphs, Torments and Risk-taking A collection of works by professional artist-teachers, who are graduates of Melbourne University’s Master of Teaching (Secondary Art) program Curated by Purnima Ruanglertbutr Frater and McCubbin Galleries, Victorian Artists Society October 2013 CONTENTS Foreword 4 Victoria McCaffrey 42 Curator's introduction 6 Milla 44 Artists 10 Liz Millsom 46 Claire Mooney 48 Seijiro Nishioka 50 Meg Andrew 12 Andria Norvelis 52 Ryan Cockburn 14 Alysia Rees 54 Ysabelle Dauguet 16 Purnima Ruanglertbutr 56 Craig Frankland 18 Clare Sanders 58 Sarah Healy 20 Leyla Tas 60 Linda Hogan 22 Ramona Tilley 62 Wesley Imms 24 Claire Virgona 64 Lis Johnson 26 Elizabeth Waghorn 66 Olivia Karpathiou 28 Lauren Welsh 68 Patsy Killeen 30 Kim Winton 70 Louise Kyriakou 32 Catherine Kayee Wong 72 Andrew Lawson 34 Cassie Linley 36 Artist biographies 74 Join Silica Liong 38 Notes 80 Aylin Llewellyn 40 Credits 81 2 | Contents Sensations of Art-making | 3 FOREWORD It is with great pleasure that I welcome you to the second annual Teacher as Art-maker Project (TAP) I would like to thank Ms Purnima Ruanglertbutr for her outstanding curatorship of this exhibition. The sheer exhibition. The works in this show demand attention by illustrating with sensitivity the triumphs, torments number of participants and the tight budgetary restrictions (this is, after all research!) has made her task and risk-taking inherent to professional artistic practice. Collectively they do more, however. Each of these even harder. Yet Purnima has produced for TAP yet another exhibition of focus, quality and meaning. -

June 2014 Forensic Dental Identification Dental Professionals and Mass Disasters Emergency Preparation Journacalifornia DENTAL ASSOCIATION and Response

June 2014 Forensic Dental Identification Dental Professionals and Mass Disasters Emergency Preparation JournaCALIFORNIA DENTAL ASSOCIATION and Response DISASTERS AND THE DENTAL OFFICE Anthony R. Cardoza, DDS You are not a market segment. You are also not a sales goal or a policy number. You are a dentist. One who deserves superior protection, exceptional service and a fair price. That’s something we understand at TDIC. Case in point, the Optimum Bundle. TDIC Optimum Bundle Good discount on Professional Liability when Professional Liability 10 % combined with Workers’ Compensation Commercial Property Better Workers’ Compensation discount on both Professional Liability + 10 % Commercial Property when combined Discounts apply to individual policies and are Optimum not cumulative. To obtain the Professional Liability premium five (5) percent, two-year discount, 20% discount on Professional Liability California dentists must complete the current TDIC Risk Management seminar. Call 800.733.0634 for current deadlines and seminar details. 10 % discount on Commercial Property 5% discount on Workers’ Compensation Bonus Additional 5% discount on Professional Liability when you take the current TDIC Risk Management seminar. Protecting dentists. It’s all we do.® 800.733.0633 | tdicsolutions.com | CA Insurance Lic. #0652783 June 2014 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 42, Nº6 DEPARTMENTS 361 The Editor/Slow to Know or Slow to Show 364 Letter to the Editor 367 Impressions 407 Practice Support/Strategic Continuing Education Planning 410 RM Matters/Considering Dating a Patient? Refer First 416 Regulatory Compliance/ HIPAA Security Risk Analysis 419 Periscope 422 Tech Trends 367 FEATURES 376 Disasters and the Dental Office An introduction to the issue. Anthony R. Cardoza, DDS 379 Forensic Dental Identification in Mass Disasters: The Current Status Training, experience and advances in technology continue to improve the efficiency of the identification process. -

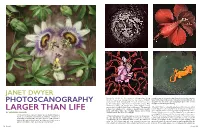

Larger Than Life Black and White Darkroom, Watching Images Appear from Since 2001 She Has Been Creating Images Using a Flatbed Scanner

JANET DWYER Being the model for her mother’s photography, along clearly see where her passion lay. Near the end of the semester, with her four other siblings, was the first step in Dwyer’s when Dwyer was unsure about continuing at university, a friend PHOTOSCANOGRAPHY enchantment with photography. “I recall being fascinated suggested she enroll in a photography program. The courses by that little square glass viewer on top of the camera. The brought back that magical feeling. whole thing really was a magic box. And eventually lovely square photos with deckled edges would arrive.” The magical Although Dwyer has extensive experience using cameras owing feeling was enhanced by visiting a neighbouring friend’s to her degrees in photography from Conestoga and Ryerson, LARGER THAN LIFE black and white darkroom, watching images appear from since 2001 she has been creating images using a flatbed scanner. BY MEHREEN SHAHID darkness under the glow of a red light. Using a flatbed scanner for producing works of art is known as scanography. In this process, the scanner replaces the camera. For the artist whose subject is nature and its many intricacies, “When I left home at 18 to attend university in New Brunswick, The lid is removed and objects are placed on the scanner glass: the process of creation offers infinite possibilities. “Nature itself my dad lent me his 35mm camera. I took a lot of photos, backgrounds usually have to be suspended over top, at a slight is my biggest inspiration,” says Janet Dwyer. “I am grateful to documenting the new landscape and people I met and lived distance. -

Workshop Descriptions

Workshop Descriptions Please Note: The workshops listed in this issue of the NYSATA News are as of the printing of this publication and are not complete. They are also subject to cancellation or iART change. For more information and current listings, please check our website www.NYSATA.org. Presenters are listed at the end of each workshop description. Using Recycled Cardboard To Build for students to put their best foot forward Painted Silk Sculptures Dreams when preparing for success. Assembled The production and commerce of Learn how to make books, puppets, and presented properly, the art portfolio decorated silk fabrics began thousands castles, and sculptures from corrugated not only demonstrates evidence of of years ago in China. Over the centuries, cardboard. Not only are these budget learning and growth in the arts, it its popularity spread around the globe savers, but they are no-fail, open-ended provides a holistic portrait of student and a variety of cultures created their projects in which students can express preparation that underscores the own distinct processes of weaving and their creativity while learning about professionalism, critical thinking dying this luxurious fabric. Synthetic architecture, rainforest animals, or even abilities, and presentation skills that fibers as substitutions for silk were the abstract relief art of Frank Stella. spell success in both college and career. developed out of necessity during World Lori Amer and Audrey Reich This workshop will cover art direction War II. In this session, you will form a and critical choices in developing a wire shape as a support, stretch a silk- Local Artistic Heritage: The Shakers, versatile portfolio for both fine arts and like fabric over it, and paint the sculpture A Unique Perspective graphic design. -

The Art of the Brain

ON TOPIC Letter from the Editor THE ART OF THE BRAIN: “Brainbow” and the Difficulty Hello Readers! of Distinguishing Science and Art I wanted to start out this edition of my bimonthly letter by thanking you all, wholeheartedly, for your readership. I like to think of SciArt in America as being in its infancy; while the pith of SAiA resides in the fascinating artists and projects we feature, I see amazing possibilities in how SAiA can grow into the larger role of serving as a major platform for all things SciArt. It is thanks to your support, and the fantastic additions to the SAiA staff, that we were able to help SAiA grow up a little this issue, and we’re thrilled to now be reaching readers across the globe. Since launching our first issue, it has become increasingly evident to me that while the greater art world is characteristically less group/movement and more individual/movement-based, the SciArt part of the art world is brimming with enthusiastic, dedicated, and inspirational artists to whom an artistic community is still a central concern. Whether it is because SciArt is riding the implicit communal energy of a recently founded art movement, because the particular artist concerns in SciArt make community more ap- pealing, or because we’re all a bunch of science nerds at heart and just like talking about science with other nerds, the degrees of separation between everyone in the SciArt world are very few, and wonderfully so. While SciArt varies across medium and subject, the drive to share the wonderous phenomena of our existence is what binds us. -

Fine Art Photography a LEVEL ART & DESIGN OPTIONS

Fine Art A LEVEL ART & DESIGN OPTIONS Photography What are the options available? In Art and Design we offer 2 separate courses that are based on specialist areas: ● Fine Art ● Photography Students can opt for the A Level course in either Fine Art or Photography dependent upon their experience at GCSE level. Both courses follow the same structure as each other, but use different materials to realise the students creative intentions. They also both encourage students to explore a range of media, artistic styles and genres. They are built around the development of imaginative and individual practical work consisting of 60% Personal Investigation (Coursework Portfolio) and 40% Set Task (exam). ● Fine Artists can select from all available media, including; drawing, painting, printmaking, photography, digital, sculpture etc. So this is a much broader approach. ● Photographers specialise in lens and light based media, through which they can use; digital photography, traditional film and chemical based photography, photograms, cyanotype, scanography, film and moving image etc. The courses are suitable for anyone who has completed either GCSE Photography or GCSE Art, or other appropriate Art & Design based specialism at GCSE which can be discussed with members of the SJWMS staff. A Level Fine Art A Level Photography Aims of the Course Almost everything around you has been created by Artists and Designers. In every job and career, there is an increasing need to be creative, imaginative and resourceful. The course allows you to: ● Develop your -

E-LIFE Evaluation Report

e-LIFE e-LEARNING VIRTUAL CENTER FOR PEOPLE WITH PHYSICAL DISABILITIES 2011-1-RO1-LEO05-15322 e-LIFE Evaluation Report e-LIFE E-LEARNING VIRTUAL CENTER FOR PEOPLE WITH PHYSICAL DISABILITIES 2011-1-RO1-LEO05-15322 This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use whit may be made of the information contained therein. LdV Project “e-LIFE” – e-LIFE INTRODUCTION The work not only individual’s having an income but also their social relations, personal satisfaction, happiness and familial relationships etc. Employment has a considerable role in solving the problems of disabled people. What needs to be accepted here is the fact that disabled people needs to be employed more than able bodied people. However, it goes without saying that one of the most disadvantageous fractions of the society in terms of employment is disabled people. Disabled people encounter many challenges in working life. They are more or less a part of employment market depending on the development level of the countries in EU. Attitudes of disabled people as well as their employment are of much importance. However, disabled citizens are maybe the group which feels the discrimination in working life most. Companies prepare job analyses and definitions without considering disabled workers which particularly impacts working methods of disabled people who are newly employed. Also, working place buildings are constructed ignoring some certain physical needs of disabled people which do not allow them to work comfortably. They receive less money due mainly to their being disabled though they do the same work as others. -

Washington State High School PHOTOGRAPHY Competition 2018 Facts

Washington State High School PHOTOGRAPHY Competition 2018 facts What is the Washington State High School Photography Competition? An annual event designed to showcase the finest photographers in Washington state high schools. Watch our new three minute video on Facebook: www.facebook.com/Washington-State-High-School-Photography-Competition-1097209700373589/home Who can enter? Any student grades 9-12 currently enrolled in a Washington state public, private or alternative high school. Why enter? Here’s an opportunity to have your photograph exhibited at the Seattle Art Museum, ©Colton Van Til, Woodinville H.S. see your photo featured on a Jones Soda bottle, shoot like a pro at a Sounders FC 2nd place ABSTRACT soccer match, and bank a little prize money—cha-ching! Deadline All entries must be in our possession by 3PM Saturday April 28th, 2018. If you’re shipping entries via post office, please use this address: Kenmore Camera PO Box 82467 Kenmore, WA 98028. For UPS, Fed X, etc. and hand delivery, please use: Kenmore Camera 6708 NE 181st Street Kenmore, WA 98028. All entries from a ©Madison Davis, Glacier Peak H.S. single school must be delivered together with a fully completed entry form, student list, 2nd place CAMERA PHONE and one single payment - absolutely no exceptions. Please mark boxes attn: Washing- ton State Photo. For directions visit www.kenmorecamera.com Entry Fee $3 per entry. A limit of 6 entries per student. Purchase orders, checks and bank cards accepted. Cash is not accepted. Please make purchase order or check payable to Kelly Atkinson. Prizes (see page 12 for full details) • Best in Show: $250 • Students winning 1st place in the other 10 categories will receive a check for $100.