The Art of the Brain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multimedia Systems DCAP303

Multimedia Systems DCAP303 MULTIMEDIA SYSTEMS Copyright © 2013 Rajneesh Agrawal All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara CONTENTS Unit 1: Multimedia 1 Unit 2: Text 15 Unit 3: Sound 38 Unit 4: Image 60 Unit 5: Video 102 Unit 6: Hardware 130 Unit 7: Multimedia Software Tools 165 Unit 8: Fundamental of Animations 178 Unit 9: Working with Animation 197 Unit 10: 3D Modelling and Animation Tools 213 Unit 11: Compression 233 Unit 12: Image Format 247 Unit 13: Multimedia Tools for WWW 266 Unit 14: Designing for World Wide Web 279 SYLLABUS Multimedia Systems Objectives: To impart the skills needed to develop multimedia applications. Students will learn: z how to combine different media on a web application, z various audio and video formats, z multimedia software tools that helps in developing multimedia application. Sr. No. Topics 1. Multimedia: Meaning and its usage, Stages of a Multimedia Project & Multimedia Skills required in a team 2. Text: Fonts & Faces, Using Text in Multimedia, Font Editing & Design Tools, Hypermedia & Hypertext. 3. Sound: Multimedia System Sounds, Digital Audio, MIDI Audio, Audio File Formats, MIDI vs Digital Audio, Audio CD Playback. Audio Recording. Voice Recognition & Response. 4. Images: Still Images – Bitmaps, Vector Drawing, 3D Drawing & rendering, Natural Light & Colors, Computerized Colors, Color Palletes, Image File Formats, Macintosh & Windows Formats, Cross – Platform format. 5. Animation: Principle of Animations. Animation Techniques, Animation File Formats. 6. Video: How Video Works, Broadcast Video Standards: NTSC, PAL, SECAM, ATSC DTV, Analog Video, Digital Video, Digital Video Standards – ATSC, DVB, ISDB, Video recording & Shooting Videos, Video Editing, Optimizing Video files for CD-ROM, Digital display standards. -

1 Bibliografia

Paolo Albani e Berlinghiero Buonarroti AGA MAGÉRA DIFÚRA Dizionario delle lingue immaginarie Zanichelli, 1994 e 2011 e Les Belles Lettres 2001 e 2010 BIBLIOGRAFIA I testi evidenziati in grassetto sono, nello specifico campo di ricerca (ad esempio: lingue filosofiche, lingue immaginarie di tipo letterario, lingue internazionali ausiliarie, ecc.), opere fondamentali. Aarsleff, Hans, Da Locke a Saussure. Saggi sullo studio del linguaggio e la storia delle idee, Bologna, il Mulino, 1984. Abbott, Edwin A., Flatlandia. Racconto fantastico a più dimensioni, 1ª ed., Milano, Adelphi, 1966, 12ª ed. 1992. Academia pro Interlingua, Torino, 1921-1927, fascicoli consultati 32. Accame, Vincenzo, Il segno poetico. Materiali e riferimenti per una storia della ricerca poetico- visuale e interdisciplinare, Milano, Edizioni d'Arte Zarathustra - Spirali Edizioni, 1981. Adams, Richard, La valle dell'orso, Milano, Rizzoli, 1976. Agamben, Giorgio, "Pascoli e il pensiero della voce", introduzione a: Pascoli, Giovanni, Il fanciullino, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1982, pp. 7-21. Agamben, Giorgio, "Un enigma della Basca", in: Delfini, Antonio, "Note di uno sconosciuto. Inediti e altri scritti", Marka, 27, 1990, pp. 93-96. Airoli, Angelo, Le isole mirabili. Periplo arabo medievale, Torino, Einaudi, 1989. Albani, Paolo, a cura di, "Piccola antologia dei linguaggi immaginari", Tèchne, 3, 1989, pp. 79-93. Albani, Paolo, "Il gioco letterario tra accademici informi, patafisici e oulipisti italiani", in: Albani, Paolo, a cura di, Le cerniere del colonnello, Firenze, Ponte alle Grazie, 1991, pp. 7-23. Alembert, Jean-Baptiste Le Rond d', "Caractère", in: Diderot, Denis e Alembert, Jean-Baptiste Le Ronde d', a cura di, Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences des arts et des métiers. -

The D.A.P. Catalog Spring 2019 Au/Nz

AU/NZ THE D.A.P. CATALOG SPRING 2019 William Klein: Celebration Text by William Klein. Here, looking back from the perspective of his 90 years, William Klein selects his favorite works, those that he considers to be the very best he has made over the course of his long career, in order to pay homage to the medium of photography itself. This book, appropriately titled Celebration, provides a tour of his most emblematic works, traversing New York, Rome, Moscow, Madrid, Barcelona and Paris, in powerful black and white or striking color. The book also includes a text by the author in which he reflects upon the photographic art and explains what prompted him to make this director’s cut, this exceptionally personal selection. A small-format but high-voltage volume, in page after page Celebration makes it clear why Klein’s achievement is one of the summits of contemporary photography. Born in New York in 1928, William Klein studied painting and worked briefly as Fernand Léger’s assistant in Paris, but never received formal training in photography. His fashion work has been featured prominently in Vogue magazine, and has also been the subject of several iconic photo books, including Life Is Good and Good for You in New York (1957) and Tok yo (1964). In the 1980s, he turned to film projects and has produced many memorable documentary and feature films, such as Muhammed Ali, the Greatest (1969). Klein currently lives and works in Paris, France. His works are held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among others. -

Art and Science: Seen As Dichotomous Practiced As Dependent Hannah Green

Art and Science: Seen as Dichotomous Practiced as Dependent Hannah Green Department of Art & Art History Honors Thesis University of Colorado at Boulder April 7, 2014 Thesis Advisor Melanie Walker | Art & Art History Committee Members Shu-Ling Chen Berggreen | Journalism & Mass Communication Françoise Duressé | Art & Art History 1 Abstract: Art and science have an undeniable connection. Many artists and scientists work with or in both fields, however, public discourse and educational structure has created the notion that the subjects are completely disparate. Art and science are divided in classes, majors, and degrees. Furthermore, science is typically required from elementary to collegiate levels of academia, whereas art is optional. Both fields, however, work through creativity by analyzing and critiquing the world. In my thesis work, Death Becomes Us, I have collected flora and fauna, which I later scanned on high-resolution scanners. The resulting large-scale prints (24” wide) reveal complexities of the specimens that evade 20/20 eyesight. The bees and flowers are all dead thus indicating the major colony collapse of pollinators that play a fundamental role in the world from ecology to economy. My work treads the line between the subjects of art and science and aims to bridge the divide that the public sees in the subjects by appealing to both fields, conceptually and aesthetically. By looking at artists and scientists it is clear that the separation that has occurred comes from a change that needs to take place from the bottom up. In other words, art and science need to be integrated in order to eliminate the hierarchy that has become mainstream thought. -

Pin Faculty Directory

Harvard University Program in Neuroscience Faculty Directory 2019—2020 April 22, 2020 Disclaimer Please note that in the following descripons of faculty members, only students from the Program in Neuroscience are listed. You cannot assume that if no students are listed, it is a small or inacve lab. Many faculty members are very acve in other programs such as Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Molecular and Cellular Biology, etc. If you find you are interested in the descripon of a lab’s research, you should contact the faculty member (or go to the lab’s website) to find out how big the lab is, how many graduate students are doing there thesis work there, etc. Program in Neuroscience Faculty Albers, Mark (MGH-East)) De Bivort, Benjamin (Harvard/OEB) Kaplan, Joshua (MGH/HMS/Neurobio) Rosenberg, Paul (BCH/Neurology) Andermann, Mark (BIDMC) Dettmer, Ulf (BWH) Karmacharya, Rakesh (MGH) Rotenberg, Alex (BCH/Neurology) Anderson, Matthew (BIDMC) Do, Michael (BCH—Neurobio) Khurana, Vikram (BWH) Sabatini, Bernardo (HMS/Neurobio) Anthony, Todd (BCH/Neurobio) Dong, Min (BCH) Kim, Kwang-Soo (McLean) Sahay, Amar (MGH) Arlotta, Paola (Harvard/SCRB) Drugowitsch, Jan (HMS/Neurobio) Kocsis, Bernat (BIDMC) Sahin, Mustafa (BCH/Neurobio) Assad, John (HMS/Neurobio) Dulac, Catherine (Harvard/MCB) Kreiman, Gabriel (BCH/Neurobio) Samuel, Aravi (Harvard/ Physics) Bacskai, Brian (MGH/East) Dymecki, Susan(HMS/Genetics) LaVoie, Matthew (BWH) Sanes, Joshua (Harvard/MCB) Baker, Justin (McLean) Engert, Florian (Harvard/MCB) Lee, Wei-Chung (BCH/Neurobio) Saper, Clifford -

Inspiration and the Oulipo

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 29 Issue 1 Article 2 1-1-2005 Inspiration and the Oulipo Chris Andrews University of Melbourne Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Andrews, Chris (2005) "Inspiration and the Oulipo ," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1590 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Inspiration and the Oulipo Abstract In the Ion and the Phaedrus Plato establishes an opposition between technique and inspiration in literary composition. He has Socrates argue that true poets are inspired and thereby completely deprived of reason. It is often said that the writers of the French collective known as the Oulipo have inverted the Platonic opposition, substituting a scientific conception of technique—formalization—for inspiration. Some of the group's members aim to do this, but not the best-known writers. Jacques Roubaud and Georges Perec practice traditional imitation alongside formalization. Imitation is a bodily activity with an important non-technical aspect. Raymond Queneau consistently points to an indispensable factor in literary composition that exceeds both formalization and imitation but is inimical to neither. Sometimes he calls this factor "inspiration"; sometimes he speaks of "the unknown" and the "the unpredictable," which must confirm the writer's efforts and intentions. -

Art and Science: Seen As Dichotomous Practiced As Dependent Hannah Green University of Colorado Boulder

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CU Scholar Institutional Repository University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2014 Art and Science: Seen as Dichotomous Practiced as Dependent Hannah Green University of Colorado Boulder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/honr_theses Recommended Citation Green, Hannah, "Art and Science: Seen as Dichotomous Practiced as Dependent" (2014). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 107. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Honors Program at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Art and Science: Seen as Dichotomous Practiced as Dependent Hannah Green Department of Art & Art History Honors Thesis University of Colorado at Boulder April 7, 2014 Thesis Advisor Melanie Walker | Art & Art History Committee Members Shu-Ling Chen Berggreen | Journalism & Mass Communication Françoise Duressé | Art & Art History 1 Abstract: Art and science have an undeniable connection. Many artists and scientists work with or in both fields, however, public discourse and educational structure has created the notion that the subjects are completely disparate. Art and science are divided in classes, majors, and degrees. Furthermore, science is typically required from elementary to collegiate levels of academia, whereas art is optional. Both fields, however, work through creativity by analyzing and critiquing the world. In my thesis work, Death Becomes Us, I have collected flora and fauna, which I later scanned on high-resolution scanners. -

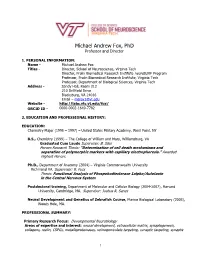

Michael Andrew Fox, Phd Professor and Director

Michael Andrew Fox, PhD Professor and Director 1. PERSONAL INFORMATION: Name - Michael Andrew Fox Titles - Director, School of Neuroscience, Virginia Tech Director, Fralin Biomedical Research Institute neuroSURF Program Professor, Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, Virginia Tech Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Tech Address - Sandy Hall, Room 212 210 Drillfield Drive Blacksburg, VA 24016 Email – [email protected] Website - http://labs.vtc.vt.edu/fox/ ORCID ID - 0000-0002-1649-7782 2. EDUCATION AND PROFESSIONAL HISTORY: EDUCATION: Chemistry Major (1995 – 1997) – United States Military Academy, West Point, NY B.S., Chemistry (1999) – The College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA Graduated Cum Laude Supervisor: B. Siles Honors Research Thesis: “Determination of cell death mechanisms and separation of polymorphic markers with capillary electrophoresis.” Awarded Highest Honors. Ph.D., Department of Anatomy (2004) – Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond VA. Supervisor: B. Fuss Thesis: Functional Analysis of Phospohodiesterase 1alpha/Autotaxin in the Central Nervous System Postdoctoral training, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology (2004-2007), Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Supervisor: Joshua R. Sanes Neural Development and Genetics of Zebrafish Course, Marine Biological Laboratory (2005), Woods Hole, MA. PROFESSIONAL SUMMARY: Primary Research Focus: Developmental Neurobiology Areas of expertise and interest: neural development, extracellular matrix, synaptogenesis, collagens, reelin, CSPGs, metalloproteinases, -

Ariadna Culpan No Images

Influences on preservice teachers’ attitudes to ICT integration in and through visual arts education: A search for a creative synthesis A thesis submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ariadna (Arda) Culpan Cert. Art, Cert. Ed., Art and Craft Teaching, B.Ed., M.Ed. School of Education College of Design and Social Context Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT University) August 2012 i Declaration I certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the thesis is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged; and, ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed. Signed: Arda Culpan Date: March 27, 2013 DECLARATION ii Acknowledgments This thesis would not have begun without the support of my first, albeit short-term supervisor Professor Nicola Yelland whose belief in the worth of the study and insightful feedback during its formulation provided the much needed courage to commence the Doctoral journey. I am also deeply indebted to Associate Professor Heather Fehring for her overall support and assistance with the RMIT Human Research Ethics application, and for her wise and warm encouragement after Professor Yelland left the university. Gratitude beyond words is extended to my supervisor Professor David Forrest without whom this thesis would not be. -

PDF-Photon | Icon

Photon | Icon darktaxa-project.net Artists: Banz+Bowinkel, Arno Beck, Group-Exhibition, Galerie Falko Alexander, Alex Grein, Beate Gütschow, Florian Kuhlmann, 4.-31.5.2019, Cologne, Curated by Falko Alexander Achim Mohné, Susan Morris, Michael Reisch, and Michael Reisch Ria Patricia Röder, Roland Schappert Photon | Icon jeweiligen Produktionsprozesse steht bei allen beteiligten KünstlerInnen aber eine Entscheidung für ein physikalisch existentes „Bildobjekt“ mit Unter zeitgenössischen digitalen Bedingungen ist derzeit völlig unklar, was mit Körper, Masse und Ausdehnung im realen (Ausstellungs-) Raum als finale dem Begriff „Fotografie“ (sowohl im künstlerischen, als auch im allgemeinen Erscheinungsform der Arbeit. Das „Bild“ wird als substanzielle, faktische und Gebrauch) eigentlich gemeint ist, bzw. ob und wie man dieses Feld sinnvoll materiale Erscheinung thematisiert, dem im Digitalen virulenten Thema der definieren soll. Auflösung und Immersion wird mit einem Gegenkonzept, einer eindeutigen Diese Frage stellt sich vehement im Hinblick auf die neuen digitalen Entscheidung für den realen Raum (Erfahrungsraum) begegnet. Möglichkeiten und Anwendungen. Die Ausstellung Photon | Icon bringt nun in In dem Dreiecksverhältnis Realität - Virtualität - Digitalität wird die Frage einer Art offenen Versuchsanordnung Arbeiten von KünstlerInnen zusammen, gestellt, inwieweit das „Fotografische“ als normative Kraft nicht nur für die mit Digitaler Fotografie, CGI, Photogrammetrie, Scanografie, Augmented die neuen Arbeitsweisen und digitalen Werkzeuge, -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum vitae Prof. Dr. Thomas Misgeld (*August 30, 1971) Institute of Neuronal Cell Biology, Technical University of Munich, Biedersteiner Str. 29, 80803 München phone: (+49-89) 4140-3512, fax: (+49-89) 4140-3352 [email protected] http://www.misgeld-lab.me.tum.de/new/ Training 1991 - 1998 Studies of Medicine, TU Munich 1993 - 1999 Dr. med. (Neuroimmunology), ‘summa cum laude’, Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology, Supervisor: H. Wekerle 1998 - 2000 Resident (“Arzt im Praktikum”), LMU Munich, Germany 2000 - 2004 Postdoctoral fellow with Jeff Lichtman and Joshua Sanes, Washington University in St. Louis 2004 - 2006 Postdoctoral fellow with Jeff Lichtman and Joshua Sanes, Harvard University, Cambridge Academic positions & appointments since 2006 Faculty, Neurobiology Course. Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole 2006 - 2011 Sofja Kovalevskaja Group Leader, TU Munich 2008 - 2012 Hans Fischer Tenure Track Fellow Institute of Advanced Studies, TU Munich since 2009 Member, CIPSM Excellence Cluster 2009 - 2012 Tenure Track W3 Professor for Biomolecular Sensors, TU Munich Principal Investigator, CIPSM Excellence Cluster since 2012 Full Professor and Director, Institute of Neuronal Cell Biology, TU Munich Co-Coordinator and Principal Investigator, SyNergy Excellence Cluster Member, German Center for Neurdegenerative Diseases Associate Investigator, CIPSM Excellence Cluster since 2013 Member, Munich Center for Neuroscience (MCN) since 2014 Faculty, TUM Graduate School of Bioengineering (GSB) Associate Faculty, Graduate School of Systems -

Institute of Medicine

Committee on Science, Technology, and Law Thirty Third Meeting Millikan Library Board Room California Institute of Technology 1200 E. California Blvd Pasadena, CA 91125-3200 March 9-10, 2017 Thursday, 9 March 2017 OPEN SESSION 10:00 am Welcome/Opening Remarks CSTL Co-Chairs: David Baltimore, California Institute of Technology David Tatel, U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit 10:10 pm Fake News: The Role of Technology and Law Moderator: Jennifer Mnookin, University of California, Los Angeles Speakers: Deborah Blum, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lucas Graves, University of Wisconsin Hunt Allcott, New York University 12:00 pm Lunch 1:00 pm Congressional Challenges to the Administrative State Moderator: David Tatel, U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit Speakers: Nicholas Parrillo, Yale University Miriam Seifter, University of Wisconsin David Doniger, Natural Resources Defense Council 1 2:30 pm The Role of Expertise Moderator: Alta Charo, University of Wisconsin Speakers: Tom Nichols, U.S. Naval War College Jonathan Samet, University of Southern California Fiona Harrison, California Institute of Technology 4:00 pm Break 4:15 pm Sc ience5:30 in thepm Trump Administration Moderator: David Baltimore, California Institute of Technology Speaker: Rush Holt, American Association for the Advancement of Science 5:15 pm Adjourn 6:00 pm Reception 6:00 pmand Dinner for Committee, Speakers, and Guests The Athenaeum: Main Lounge California Institute of Technology 551 South Hill Avenue Pasadena, CA 91106 2 Committee on Science, Technology, and Law Thirty Third Meeting Millikan Library Board Room California Institute of Technology 1200 E. California Blvd Pasadena, CA 91125-3200 March 9-10, 2017 Friday, March 10, 2017 OPEN SESSION 8:00 am Breakfast 8:30 am Welcome/Opening Remarks CSTL Co-Chairs: David Baltimore, California Institute of Technology David Tatel, U.S.