Proust and Dickens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testament of Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 P.461

Testament of Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 p.461 Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 [page 461] I, Thomas Carlyle of 5 Great Cheyne Row, Chelsea in the County of Middlesex Esquire declare this to be my last Will and Testament Revoking all former Will I direct all my just debts, funeral and testamentary expences to be paid as soon as may be after my decease And it is my express instruction that since I cannot be laid in the Grave at Haddington I shall be placed beside my Father and Mother in the Churchyard of Ecclefechan. I appoint my Brother John Aitken Carlyle, Doctor of Medicine and my friend John Foster of Palace Gate House, Kensington, Esquire Executors and Trustees of this my Will. If my said Brother should die in my lifetime I appoint my Brother James Carlyle to be an Executor and Trustee in his stead and if the said John Forster should die in my [p.463] my lifetime I appoint my friend James Anthony Froude to be an Executor and Trustee in his stead. I give to my dear and ever helpful Brother John A. Carlyle my Leasehold messuage in Great Cheyne Row in which I reside subject to the rent and covenants under which I hold the same and all such of my Furniture plate linen china books prints pictures and other effects therein as are not hereinafter bequeathed specifically My Brother John has no need of my money or help and therefore in addition to this small remembrance I bequeath to him only the charge of being Executor of my Will and of seeing everything peaceably fulfilled If he survives me as is natural he will not refuse My poor and indeed almost pathetic collection of books (with the exception of those hereinafter specifically given) I request him to accept as a memento of me while he stays behind I give my Watch to my Nephew Thomas the son of my Brother Alexander "Alicks Tom" as a Memorial of the affection I have for him and of my thankful (and also hopeful) approval of all that I have ever got to know or surmise about him. -

Arguing with the Coloniser: Linguistic Strategies in John Jacob Thomas's Froudacity (1889) 1

151 JANA GOHRISCH Arguing with the Coloniser: Linguistic Strategies in John Jacob Thomas's Froudacity (1889) 1. Introduction In the West Indies there is indefinite wealth waiting to be developed by intelligence and capital; and men with such resources, both English and American, might be tempted still to settle there, and lead the blacks along with them into more settled manners and higher forms of civilisation. But the future of the blacks, and our own influence over them for good, depend on their being protected from themselves and from the schemers who would take advantage of them. […] As it has been in Hayti, so it must be in Trinidad if the Eng- lish leave the blacks to be their own masters. […] [T]he keener-witted Trinidad blacks are watching as eagerly as we do the development of the Irish problem. They see the identity of the situation. (Froude 1888, 79; 86; 87) Anyhow, Mr. Froude's history of the Emancipation may here be amended for him by a reminder that, in the British Colonies, it was not Whites as masters, and Blacks as slaves, who were affected by that momentous measure. In fact, 1838 found in the British Colonies very nearly as many Negro and Mulatto slave-owners as there were white. Well then, these black and yellow planters received their quota, it may be presumed, of the £ 20,000,000 sterling indemnity. They were part and parcel of the proprietary body in the Colonies, and had to meet the crisis like the rest. They were very wealthy, some of these Ethiopic accomplices of the oppressors of their own race. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

1 the Wilson-Smuts Synthesis: Racial Self

The Wilson-Smuts Synthesis: Racial Self-Determination and the Institutionalization of World Order A thesis submitted by Scott L. Malcomson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations Tufts University Fletcher School of International Law and Diplomacy January 2020 Adviser: Jeffrey W. Taliaferro ©2019, Scott L. Malcomson 1 Table of Contents I: Introduction 3 II: Two Paths to Paris. Jan Smuts 8 Woodrow Wilson 26 The Paths Converge 37 III: Versailles. Wilson Stays Out: Isolation and Neutrality 43 Lloyd George: Bringing the Empire on Board 50 Smuts Goes In: The Rise of the Dominions 54 The Wilson-Smuts Synthesis 65 Wilson Undone 72 The Racial Equality Bill 84 IV: Conclusion 103 Bibliography 116 2 I: Introduction When President Woodrow Wilson left the United States for Europe at the end of 1918, he intended to create a new structure for international relations, based on a League of Nations, that would replace the pre-existing imperialist world structure with one based on national and racial (as was said at the time) self-determination. The results Wilson achieved by late April 1919, after several months of near-daily negotiation in Paris, varied between partial success and complete failure.1 Wilson had had other important goals in Paris, including establishing a framework for international arbitration of disputes, advancing labor rights, and promoting free trade and disarmament, and progress was made on all of these. But in terms of his own biography and the distinctive mission of U.S. foreign policy as he and other Americans understood it, the anti- imperial and pro-self-determination goals were paramount. -

Curriculum Vitae Andrew Jackson O'shaughnessy

Curriculum Vitae Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy Personal Details Home Address: 308 E. Market Street, #305, Charlottesville, VA 22902. Work Address: Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. Post Office, Box 316 Charlottesville, Virginia 22902. E-Mail: [email protected] Telephone: wk. 434-984-7501. hm. 434-244-3541. Nationality: US and British (dual citizen). Education 1988: Oriel College, Oxford University. Doctor of Philosophy (D.Phil.) 1987: Oriel College, Oxford University. Modern History M.A. 1982 Oriel College, Oxford University. Modern History B.A. 1979: Columbia University, New York (School of General Studies). Professional Experience 2003 Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello. 2 • Fellowship program and seminars. • International and domestic conferences. • The Jefferson Library • Adult Enrichment Programs (outreach). • Publications. • Archaeology department • Research department • Documentary editing department of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. Retirement Series (published by Princeton University Press). Professor of American History, University of Virginia. 2002 Professor of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. 1998-03: Chair of the Department of History, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh. 1997 Associate Professor of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh (tenured). 1990-97: Assistant Professor (tenure-track) of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. 1989-90: Visiting Assistant Professor of American History, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas. 1988-89: Master, Eton College, Windsor, Berkshire. 1988: Teacher, The Forest School, London. 1987-90: Tutor for Davidson College (North Carolina), Summer Program in Eighteenth Century Studies, Wolfson College, Cambridge University. 1986-87: Lecturer, Lincoln College, Oxford University. -

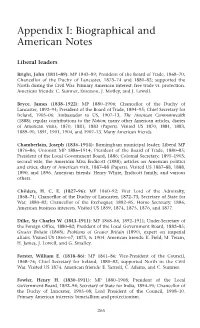

Appendix I: Biographical and American Notes

Appendix I: Biographical and American Notes Liberal leaders Bright, John (1811–89): MP 1843–89; President of the Board of Trade, 1868–70; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1873–74 and 1880–82; supported the North during the Civil War. Primary American interest: free trade vs. protection. American friends: C. Sumner, Emerson, J. Motley, and J. Lowell. Bryce, James (1838–1922): MP 1880–1906; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1892–94; President of the Board of Trade, 1894–95; Chief Secretary for Ireland, 1905–06; Ambassador to US, 1907–13; The American Commonwealth (1888); regular contributions to the Nation; many other American articles, diaries of American visits, 1870, 1881, 1883 (Papers). Visited US 1870, 1881, 1883, 1889–90, 1891, 1901, 1904, and 1907–13. Many American friends. Chamberlain, Joseph (1836–1914): Birmingham municipal leader; Liberal MP 1876–86; Unionist MP 1886–1914; President of the Board of Trade, 1880–85; President of the Local Government Board, 1886; Colonial Secretary, 1895–1903; second wife, the American Miss Endicott (1888); articles on American politics and cities; diary of American visit, 1887–88 (Papers). Visited US 1887–88, 1888, 1890, and 1896. American friends: Henry White, Endicott family, and various others. Childers, H. C. E. (1827–96): MP 1860–92; First Lord of the Admiralty, 1868–71; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1872–73; Secretary of State for War, 1880–82; Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1882–85; Home Secretary, 1886; American business interests. Visited US 1859, 1874, 1875, 1876, and 1877. Dilke, Sir Charles W. (1843–1911): MP 1868–86, 1892–1911; Under-Secretary of the Foreign Office, 1880–82; President of the Local Government Board, 1882–85; Greater Britain (1868); Problems of Greater Britain (1890); expert on imperial affairs. -

Supplementarynoteschapter4.Pdf (186.7Kb)

Koditschek, Liberalism, Imperialism and the Historical Imagination Supplementary Notes 4 Theodore Koditschek Supplementary Notes to Chapter Four Reimagining a Greater Britain: J.A. Froude: Counterromance and controversy Note to Reader: These supplementary notes consist primarily of extended references and explanations that were cut from the original book manuscript for reasons of space. In a few instances, however, they constitute more extended subordinate narratives (with accompanying references), which are related to the book’s themes, but were left out because they would have deflected from the central argument and analysis of the volume. These supplementary notes are coordinated to the footnote numbers for chapter four of Liberalism, Imperialism and the Historical Imagination: Nineteenth Century Visions of a Greater Britain, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2011). 5. Froude had always taken a strong interest in history. What presented itself as a crisis in religious faith, he experienced more fundamentally as a crisis over the validity of history. As he wrote of his abortive collaboration with Newman in 1845, “The Saint’s Life‐writing had to be abandoned as hopeless, but my two‐year study had turned the historical ground where I had hoped to find a footing a bottomless morass, covered over by a thin skin of imaginative stories, where nothing grew, or could grow but grass and bog myrtle.” Quoted in Waldo Hilary Dunn, James Anthony Froude, A Biography, I, 18181856, (Oxford, 1961); II, 185794 (Oxford, 1963), I, 72. Froude’s solution was simply to move out of the bottomless morass of pure religion, to the higher ground of a kind of history (i.e. -

Imperial Rhetoric in Travel Literature of Australia 1813-1914. Phd Thesis, James Cook University

This file is part of the following reference: Jensen, Judith A Unpacking the travel writers’ baggage: imperial rhetoric in travel literature of Australia 1813-1914. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/10427 PART THREE: MAINTAINING THE CONNECTION Imperial rhetoric and the literature of travel 1850-1914 Part three examines the imperial rhetoric contained in travel literature in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries which worked to convey an image of Australia’s connection to Britain and the empire. Through a literary approach that employed metaphors of family, travel writers established the perception of Australia’s emotional and psychological ties to Britain and loyalty to the Empire. Contemporary theories about race, the environment and progress provided an intellectual context that founded travel writers’ discussions about Australia and its physical links to Britain. For example, a fear of how degeneration of the Anglo-Saxon race would affect the future of the British Empire provided a background for travellers’ observations of how the Anglo-Saxon race had adapted to the Australian environment. Environmental and biological determinism explained the appearance of Anglo-Australians, native-born Australians and the Australian type. While these descriptions of Australians were not always positive they emphasised the connection of Australians to Britain and the Empire. Fit and healthy Australians equated to a fit and healthy nation and a robust and prestigious empire. Travellers emphasised the importance of Australian women to this objective, as they were the moral guardians of the nation and the progenitors of the ensuing generation. -

Archives and Special Collections

Archives and Special Collections Dickinson College Carlisle, PA COLLECTION REGISTER Name: Conway, Moncure Daniel (1832-1907) MC 1999.6 Material: Family Papers (1729-1955) Volume: 1.5 linear feet (Document Boxes 1-3, 3 Oversized Folders, 21 Photograph Folders) Donation: Gifts of Various Donors Usage: These materials have been donated without restrictions on usage. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Moncure Daniel Conway was born on March 17, 1832 in Stafford County, Virginia, the son of Walker Peyton Conway and Margarete Daniel. Walker was a justice in the county court, a trustee of Dickinson College from 1848-1865, and a prominent slaveholder in the county. Margarete was a homeopathic doctor that treated both black and white equally and did not see eye-to-eye with her husband on the issue of slavery. Disinterested with the activities of the men in his family, young Moncure was most influenced by his women relatives and learned a great deal of compassion from them. Moncure always showed a great deal of respect for his family’s slaves, and at one point took it upon himself to help nearly thirty slaves escape to freedom in Ohio. He was also unsatisfied with the family’s devout religious practices and after becoming acquainted with the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, young Moncure began to search for more personal fulfillment in religion. Moncure Conway was sent north at the age of 15 to attend Dickinson College and graduated with the class of 1849. While at Dickinson, under abolitionist professors, he firmly allied himself with the North and turned his energy toward emancipation. -

Inventory Acc.11388 Ashburton Papers

Inventory Acc.11388 Ashburton Papers National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Papers of William Bingham Baring, second Baron Ashburton (succeeded 1848; 1799- 1864), his first wife (m.1823) Lady Harriet Mary Montagu (?1805-1857, eldest daughter of the 6th Earl of Sandwich) and his second wife (m.1858) Louisa Caroline Stewart Mackenzie (1827-1903). Also papers of his only child surviving to adulthood, Mary Florence (1860-1902, married William Compton, fifth Marquess of Northampton), and their extended family, especially Louisa’s mother, the Hon. Mary Frederica Stewart Mackenzie of Seaforth (formerly Lady Hood) (1783-1862). These individuals are referred to below as Bingham, Harriet, Louisa, Mary and Mrs Stewart Mackenzie respectively. The importance of the papers lies in the enormous range of the correspondents: politicians British and French, writers, artists. Bingham was an MP from 1826 until he succeeded to the peerage, and this, as well as his family of bankers and politicians gave him a wide-ranging acquaintance. Harriet too was deeply interested in politics, and also knew many writers, presiding over a salon and conducting a large correspondence. Louisa was a well-known figure in society, especially in the artistic world. Mrs Stewart Mackenzie was a close friend of Sir Walter Scott. Particularly notable are the correspondences with Scott, Thomas and Jane Carlyle, Dr John Brown, -

The Ideological Watershed in Victorian England

CRISIS WITHOUT REVOLUTION : THE IDEOLOGICAL WATERSHED IN VICTORIAN ENGLAND The English ruling classes under Queen Victoria prided themselves upon the dubious distinction that their suzerainty over three kingdoms was impervious to the upheavals that swept the European mainland. They at least had had the foresight to tame their monarchy with an oli- garchy of wealth. « Your aristocracy and bourgeoisie », Auguste Comte complained to an Oxford disciple in the 1850s, « ... consider England wholly protected in advance against the present crisis of the West by their dynastic Revolution of 1688 » I. Subsequent events confirmed the safety of the ruling classes, although their sense of security was at least partly misplaced. Limited monarchies and reformed parliaments may fend off revolution, but not by virtue of their existence. Laws must be passed as deterrents, force must be used to stem unrest ; and in the « first industrial nation », where the manual working class was numeri- cally dominant, the maintenance of public order also required a massive mobilization of consent. It did not take Elie Halëvy to point out that Methodism helped prevent a revolution in the 1790s, however much his famous thesis has had to be qualified. Victorians themselves, who peer- ed piously through the mists at republican France, fancied their isles a bastion of Christian civilization. Endemic evangelicalism and natural theology were proof to atheistic materialism. The salvos of « false phi- losophy » passed harmlessly through the religious atmosphere, like bul- lets through a fog. Ideologically, as well as institutionally, Victorian England lay shrouded in reaction to the causes and the consequences of the French Revolution. -

12. Shades of Bruce: Independence and Union in First-World War Scottish Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Strathclyde Institutional Repository 1 12. Shades of Bruce: Independence and Union in First-World War Scottish Literature David Goldie Less than two weeks into the First World War, the weekly newspaper with the widest circulation and readership in Scotland, the People’s Journal, published a stirring, if paradoxical, hand-drawn illustration plainly designed to stir up the martial spirit of patriotic Scots. Incorporating at its bottom corner a pamphlet in which Lord Kitchener called on “The Men of Scotland” to join his drive for 100,000 New Army recruits, the illustration featured Robert the Bruce, hero of Bannockburn, with behind him a crowd of eager young men mobbing the figure of Britannia who stands aloft with union flag in one hand and raised sword in the other. Above Bruce’s head and just below Britannia’s sword are the dates 1314-1914 and, just in case this implicit connection between Bannockburn and the present war is not emphatic enough, the caption at the bottom of the illustration reads “Shades of Bruce – the Same Spirit still Lives!”1 The placing of Bruce in the foreground, the bold appeal to “the Men of Scotland,” and the reminders of the sexcentenary of the Battle of Bannockburn, suggest a confident and aggressive sense of Scottish pride. But this superficial gesture of national assertiveness is qualified by the piece’s visual rhetoric. The Bruce may be the dominant physical presence occupying the foreground, but he is, in theatrical terms, upstaged by Britannia.