J. Anthony Froude . the Last Undiscovered Great Victorian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testament of Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 P.461

Testament of Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 p.461 Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 [page 461] I, Thomas Carlyle of 5 Great Cheyne Row, Chelsea in the County of Middlesex Esquire declare this to be my last Will and Testament Revoking all former Will I direct all my just debts, funeral and testamentary expences to be paid as soon as may be after my decease And it is my express instruction that since I cannot be laid in the Grave at Haddington I shall be placed beside my Father and Mother in the Churchyard of Ecclefechan. I appoint my Brother John Aitken Carlyle, Doctor of Medicine and my friend John Foster of Palace Gate House, Kensington, Esquire Executors and Trustees of this my Will. If my said Brother should die in my lifetime I appoint my Brother James Carlyle to be an Executor and Trustee in his stead and if the said John Forster should die in my [p.463] my lifetime I appoint my friend James Anthony Froude to be an Executor and Trustee in his stead. I give to my dear and ever helpful Brother John A. Carlyle my Leasehold messuage in Great Cheyne Row in which I reside subject to the rent and covenants under which I hold the same and all such of my Furniture plate linen china books prints pictures and other effects therein as are not hereinafter bequeathed specifically My Brother John has no need of my money or help and therefore in addition to this small remembrance I bequeath to him only the charge of being Executor of my Will and of seeing everything peaceably fulfilled If he survives me as is natural he will not refuse My poor and indeed almost pathetic collection of books (with the exception of those hereinafter specifically given) I request him to accept as a memento of me while he stays behind I give my Watch to my Nephew Thomas the son of my Brother Alexander "Alicks Tom" as a Memorial of the affection I have for him and of my thankful (and also hopeful) approval of all that I have ever got to know or surmise about him. -

Arguing with the Coloniser: Linguistic Strategies in John Jacob Thomas's Froudacity (1889) 1

151 JANA GOHRISCH Arguing with the Coloniser: Linguistic Strategies in John Jacob Thomas's Froudacity (1889) 1. Introduction In the West Indies there is indefinite wealth waiting to be developed by intelligence and capital; and men with such resources, both English and American, might be tempted still to settle there, and lead the blacks along with them into more settled manners and higher forms of civilisation. But the future of the blacks, and our own influence over them for good, depend on their being protected from themselves and from the schemers who would take advantage of them. […] As it has been in Hayti, so it must be in Trinidad if the Eng- lish leave the blacks to be their own masters. […] [T]he keener-witted Trinidad blacks are watching as eagerly as we do the development of the Irish problem. They see the identity of the situation. (Froude 1888, 79; 86; 87) Anyhow, Mr. Froude's history of the Emancipation may here be amended for him by a reminder that, in the British Colonies, it was not Whites as masters, and Blacks as slaves, who were affected by that momentous measure. In fact, 1838 found in the British Colonies very nearly as many Negro and Mulatto slave-owners as there were white. Well then, these black and yellow planters received their quota, it may be presumed, of the £ 20,000,000 sterling indemnity. They were part and parcel of the proprietary body in the Colonies, and had to meet the crisis like the rest. They were very wealthy, some of these Ethiopic accomplices of the oppressors of their own race. -

The Carlyle Society

THE CARLYLE SOCIETY SESSION 2006-2007 OCCASIONAL PAPERS 19 • Edinburgh 2006 President’s Letter This number of the Occasional Papers outshines its predecessors in terms of length – and is a testament to the width of interests the Society continues to sustain. It reflects, too, the generosity of the donation which made this extended publication possible. The syllabus for 2006-7, printed at the back, suggests not only the health of the society, but its steady move in the direction of new material, new interests. Visitors and new members are always welcome, and we are all warmly invited to the annual Scott lecture jointly sponsored by the English Literature department and the Faculty of Advocates in October. A word of thanks for all the help the Society received – especially from its new co-Chair Aileen Christianson – during the President’s enforced absence in Spring 2006. Thanks, too, to the University of Edinburgh for its continued generosity as our host for our meetings, and to the members who often anonymously ensure the Society’s continued smooth running. 2006 saw the recognition of the Carlyle Letters’ international importance in the award by the new Arts and Humanities Research Council of a very substantial grant – well over £600,000 – to ensure the editing and publication of the next three annual volumes. At a time when competition for grants has never been stronger, this is a very gratifying and encouraging outcome. In the USA, too, a very substantial grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities means that later this year the eCarlyle project should become “live” on the internet, and subscribers will be able to access all the volumes to date in this form. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

1 the Wilson-Smuts Synthesis: Racial Self

The Wilson-Smuts Synthesis: Racial Self-Determination and the Institutionalization of World Order A thesis submitted by Scott L. Malcomson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations Tufts University Fletcher School of International Law and Diplomacy January 2020 Adviser: Jeffrey W. Taliaferro ©2019, Scott L. Malcomson 1 Table of Contents I: Introduction 3 II: Two Paths to Paris. Jan Smuts 8 Woodrow Wilson 26 The Paths Converge 37 III: Versailles. Wilson Stays Out: Isolation and Neutrality 43 Lloyd George: Bringing the Empire on Board 50 Smuts Goes In: The Rise of the Dominions 54 The Wilson-Smuts Synthesis 65 Wilson Undone 72 The Racial Equality Bill 84 IV: Conclusion 103 Bibliography 116 2 I: Introduction When President Woodrow Wilson left the United States for Europe at the end of 1918, he intended to create a new structure for international relations, based on a League of Nations, that would replace the pre-existing imperialist world structure with one based on national and racial (as was said at the time) self-determination. The results Wilson achieved by late April 1919, after several months of near-daily negotiation in Paris, varied between partial success and complete failure.1 Wilson had had other important goals in Paris, including establishing a framework for international arbitration of disputes, advancing labor rights, and promoting free trade and disarmament, and progress was made on all of these. But in terms of his own biography and the distinctive mission of U.S. foreign policy as he and other Americans understood it, the anti- imperial and pro-self-determination goals were paramount. -

The Love Letters of Thomas Carlyle and Jane Welsh; Edited by Alexander

JANK WELSH AS A GIRL THE LOVE LETTERS OF THOMAS CARLYLE AND JANE WELSH EDITED BY ALEXANDER CARLYLE, M.A. WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS TWO IN COLOUR. TWO VOLUMES. VOL. I LONDON : JOHN LANE, THE BODLEY HEAD NEW YORK : JOHN LANE COMPANY. MCMIX Copyright in U.S.A., 1908 By JOHN LANE COMPANY . SECOND EDITION 4-4*3 V-l Set up and Electrotyped by . THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS, Mass., U.S.A. Printed by THE BALLANTYNE PRESS, Edinburgh PREFACE CARLYLE'S injunction against the publication of the Letters which passed between himself and Miss Welsh before their marriage having been already violated, it has seemed to me to be no longer prohibitive : the holy of holies having been sacrilegiously forced, dese- crated, and polluted, and its sacred relics defaced, besmirched, and held up to ridicule, any further intrusion therein for the purpose of cleansing and admitting the purifying air and light of heaven can now be attended, in the long run, by nothing but good results. If entrance into the sacred pre- cincts, with this object, be an act of sacrilege, it is at worst a very venial one ! Had there been no previous intrusion no infraction of Carlyle's inter- dict I need hardly say that nothing in the world or beneath it would have induced me to intrude therein. But what would have been rank sacri- lege at one time has now, in the altered circum- stances, become a pious duty. I offer no apology, therefore, for publishing these Letters, for in my judgment none is needed. I should rather be in- clined to apologise for not having performed so obvious a duty long ere now. -

Carlyle's Stellung Zur Deutschen Sprache Und Litteratur

CARLYLE'S STELLUNG ZUR DEUTSCHEN SPRACHE UND LITTERATUR. Die vorliegende abhandlung ist die erste einer reihe von Studien über Carlyle,-die, im material bereits zusammengestellt, im laufe der nächsten jähre veröffentlicht werden sollen. Sie umfasst in einem ersten teile die beschäftigung Carlyle's mit der deutschen litteratur bis etwa 1830, sein romanfragment, den „Wotton Reinfried", die dichterischen versuche und die Übersetzungen und stellt endlich im zweiten teile aus allen, auch aus seinen spätem werken schöpfend, jene deutschen elemente dar, die in der form von entlehnungen oder citaten in seinen stil übergingen. Der in dem Beiblatt zur Anglia (No- vember-Dezember 1898) erschienene aufsatz über den „Rein- fred" erscheint hier wesentlich erweitert. Die später folgenden bände beschäftigen sich mit der ent- stehung des „Sartor Resartus", auf den die vorliegende arbeit oft hindeutet; sie zergliedern dies werk litterargeschichtlich und stilistisch, um dann den weg nach den Vorlesungen „On Heroworship" und nach den geschichtswerken Carlyle's, ihrer technik und spräche, einzuschlagen. Abkürzungen. Die werke Carlyle's werden nach der 40 bändigen ausgäbe London, Chapmann & Hall, zitiert. Besonders bezeichnet sind: E1—7. Miscellaneous Essays Bd. 1—7. LoS Life of Schüler. T l, 2. Tales by Musaeus, Tieck; Richter, Translated from the German by Thomas Carlyle. In two volumes. SR Sartor Resartus, the Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh. FR 1—3. The French Revolution. A History. Fg I—X. History of Frederick the Great, by Thomas Carlyle. 1858—65. Anglia. N. P. X. 10 Brought to you by | University of California Authenticated Download Date | 6/7/15 1:19 PM 146 H. KRAEGER, Em. -

The Carlyle Society Papers

THE CARLYLE SOCIETY SESSION 2013-2014 OCCASIONAL PAPERS 26 • Edinburgh 2013 1 2 President’s Letter 2013-14 will be a year of changes for the Carlyle Society of Edinburgh. Those of you who receive notification of meetings by email will already have had the news that, after many years, we are leaving 11 Buccleuch Place. We have enjoyed the hospitality of Lifelong Learning for decades but they, too, are moving. So we are meeting – for this year – in the seminar room on the first floor of 18 Buccleuch Place. There is one flight of stairs (I used it for decades! It’s not bad) and we will be comfortably housed there. Usual time. The Carlyle Letters are moving steadily towards the completion of the correspondence of Thomas and Jane; with Jane’s death in 1866 we will have published all the known letters between them, and we plan to tidy off the process with some papers from the months immediately following her death, and papers more recently come to light, namely volumes 43-44. The Carlyle Letters Online are also moving steadily to catch up with the published volumes. Volume 40 was celebrated with a public lecture in Autumn 2012; volume 41 will appear in printed form in about a month’s time, and the materials for volume 42 will be going to Duke in about a week’s time from when these words are written. We are grateful to the English Literature department for access to our new premises in 18 Buccleuch Place; to Andy Laycock of the University’s printing department for Herculean efforts with our annual papers; to those members who now accept their annual mailing in electronic form, a huge saving in time and money. -

Curriculum Vitae Andrew Jackson O'shaughnessy

Curriculum Vitae Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy Personal Details Home Address: 308 E. Market Street, #305, Charlottesville, VA 22902. Work Address: Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. Post Office, Box 316 Charlottesville, Virginia 22902. E-Mail: [email protected] Telephone: wk. 434-984-7501. hm. 434-244-3541. Nationality: US and British (dual citizen). Education 1988: Oriel College, Oxford University. Doctor of Philosophy (D.Phil.) 1987: Oriel College, Oxford University. Modern History M.A. 1982 Oriel College, Oxford University. Modern History B.A. 1979: Columbia University, New York (School of General Studies). Professional Experience 2003 Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello. 2 • Fellowship program and seminars. • International and domestic conferences. • The Jefferson Library • Adult Enrichment Programs (outreach). • Publications. • Archaeology department • Research department • Documentary editing department of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. Retirement Series (published by Princeton University Press). Professor of American History, University of Virginia. 2002 Professor of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. 1998-03: Chair of the Department of History, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh. 1997 Associate Professor of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh (tenured). 1990-97: Assistant Professor (tenure-track) of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. 1989-90: Visiting Assistant Professor of American History, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas. 1988-89: Master, Eton College, Windsor, Berkshire. 1988: Teacher, The Forest School, London. 1987-90: Tutor for Davidson College (North Carolina), Summer Program in Eighteenth Century Studies, Wolfson College, Cambridge University. 1986-87: Lecturer, Lincoln College, Oxford University. -

Appendix I: Biographical and American Notes

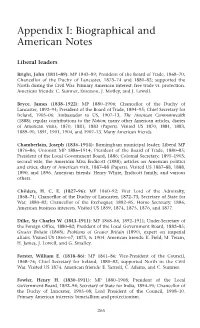

Appendix I: Biographical and American Notes Liberal leaders Bright, John (1811–89): MP 1843–89; President of the Board of Trade, 1868–70; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1873–74 and 1880–82; supported the North during the Civil War. Primary American interest: free trade vs. protection. American friends: C. Sumner, Emerson, J. Motley, and J. Lowell. Bryce, James (1838–1922): MP 1880–1906; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1892–94; President of the Board of Trade, 1894–95; Chief Secretary for Ireland, 1905–06; Ambassador to US, 1907–13; The American Commonwealth (1888); regular contributions to the Nation; many other American articles, diaries of American visits, 1870, 1881, 1883 (Papers). Visited US 1870, 1881, 1883, 1889–90, 1891, 1901, 1904, and 1907–13. Many American friends. Chamberlain, Joseph (1836–1914): Birmingham municipal leader; Liberal MP 1876–86; Unionist MP 1886–1914; President of the Board of Trade, 1880–85; President of the Local Government Board, 1886; Colonial Secretary, 1895–1903; second wife, the American Miss Endicott (1888); articles on American politics and cities; diary of American visit, 1887–88 (Papers). Visited US 1887–88, 1888, 1890, and 1896. American friends: Henry White, Endicott family, and various others. Childers, H. C. E. (1827–96): MP 1860–92; First Lord of the Admiralty, 1868–71; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1872–73; Secretary of State for War, 1880–82; Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1882–85; Home Secretary, 1886; American business interests. Visited US 1859, 1874, 1875, 1876, and 1877. Dilke, Sir Charles W. (1843–1911): MP 1868–86, 1892–1911; Under-Secretary of the Foreign Office, 1880–82; President of the Local Government Board, 1882–85; Greater Britain (1868); Problems of Greater Britain (1890); expert on imperial affairs. -

Twilight of the Godless: the Unlikely Friendship of Francis Jeffrey and Thomas Carlyle

Twilight of the Godless: The Unlikely Friendship of Francis Jeffrey and Thomas Carlyle WILLIAM CHRISTIE Edin r 13 Feb y 1830 My Dear Carlyle I am glad you think my regard for you a Mystery - as I am aware that must be its highest recommendation - I take it in an humbler sense - and am content to think it natural that one man of a kind heart should feel attracted towards another - and that a signal purity and loftiness of character, joined to great talents and something of a romantic history, should excite interest and respect. (NLS MS. 787, ff. 52-3) i I The Thomas Carlyle who knocked on Francis Jeffrey’s door at 92 George Street Edinburgh early in February of 1827 was not a young man. He was thirty two. And though Carlyle was of humble, country origins — he was the child of a rural stonemason turned small farmer — this was by no means his first time in the big city, having come here as a university student eighteen years before in 1809. Carlyle at thirty two, however, was as yet comparatively unknown, if not unpublished. His major publications — a translation of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1824) and a Life of Schiller (1825) — had not brought his name before the English speaking reading public, probably because German thought and German literature simply did not interest them enough. Thomas Carlyle was an ambitious man and never doubted his own ability, but he must at this time have doubted his chances of success, and he had just added a young wife, Jane Welsh Carlyle, to his responsibilities. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher qualify 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA UMI800-521-0600 THE CONTAGION OFLIFE: ROSSETTI, PATER, WILDE, AND THE AESTHETICIST BODY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Weninger, MA., M A., M Phil. ***** The Ohio State University 1999 Dissertation Committee: Approved By: Professor David G.