The Ideological Watershed in Victorian England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testament of Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 P.461

Testament of Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 p.461 Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 [page 461] I, Thomas Carlyle of 5 Great Cheyne Row, Chelsea in the County of Middlesex Esquire declare this to be my last Will and Testament Revoking all former Will I direct all my just debts, funeral and testamentary expences to be paid as soon as may be after my decease And it is my express instruction that since I cannot be laid in the Grave at Haddington I shall be placed beside my Father and Mother in the Churchyard of Ecclefechan. I appoint my Brother John Aitken Carlyle, Doctor of Medicine and my friend John Foster of Palace Gate House, Kensington, Esquire Executors and Trustees of this my Will. If my said Brother should die in my lifetime I appoint my Brother James Carlyle to be an Executor and Trustee in his stead and if the said John Forster should die in my [p.463] my lifetime I appoint my friend James Anthony Froude to be an Executor and Trustee in his stead. I give to my dear and ever helpful Brother John A. Carlyle my Leasehold messuage in Great Cheyne Row in which I reside subject to the rent and covenants under which I hold the same and all such of my Furniture plate linen china books prints pictures and other effects therein as are not hereinafter bequeathed specifically My Brother John has no need of my money or help and therefore in addition to this small remembrance I bequeath to him only the charge of being Executor of my Will and of seeing everything peaceably fulfilled If he survives me as is natural he will not refuse My poor and indeed almost pathetic collection of books (with the exception of those hereinafter specifically given) I request him to accept as a memento of me while he stays behind I give my Watch to my Nephew Thomas the son of my Brother Alexander "Alicks Tom" as a Memorial of the affection I have for him and of my thankful (and also hopeful) approval of all that I have ever got to know or surmise about him. -

Arguing with the Coloniser: Linguistic Strategies in John Jacob Thomas's Froudacity (1889) 1

151 JANA GOHRISCH Arguing with the Coloniser: Linguistic Strategies in John Jacob Thomas's Froudacity (1889) 1. Introduction In the West Indies there is indefinite wealth waiting to be developed by intelligence and capital; and men with such resources, both English and American, might be tempted still to settle there, and lead the blacks along with them into more settled manners and higher forms of civilisation. But the future of the blacks, and our own influence over them for good, depend on their being protected from themselves and from the schemers who would take advantage of them. […] As it has been in Hayti, so it must be in Trinidad if the Eng- lish leave the blacks to be their own masters. […] [T]he keener-witted Trinidad blacks are watching as eagerly as we do the development of the Irish problem. They see the identity of the situation. (Froude 1888, 79; 86; 87) Anyhow, Mr. Froude's history of the Emancipation may here be amended for him by a reminder that, in the British Colonies, it was not Whites as masters, and Blacks as slaves, who were affected by that momentous measure. In fact, 1838 found in the British Colonies very nearly as many Negro and Mulatto slave-owners as there were white. Well then, these black and yellow planters received their quota, it may be presumed, of the £ 20,000,000 sterling indemnity. They were part and parcel of the proprietary body in the Colonies, and had to meet the crisis like the rest. They were very wealthy, some of these Ethiopic accomplices of the oppressors of their own race. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

1 the Wilson-Smuts Synthesis: Racial Self

The Wilson-Smuts Synthesis: Racial Self-Determination and the Institutionalization of World Order A thesis submitted by Scott L. Malcomson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations Tufts University Fletcher School of International Law and Diplomacy January 2020 Adviser: Jeffrey W. Taliaferro ©2019, Scott L. Malcomson 1 Table of Contents I: Introduction 3 II: Two Paths to Paris. Jan Smuts 8 Woodrow Wilson 26 The Paths Converge 37 III: Versailles. Wilson Stays Out: Isolation and Neutrality 43 Lloyd George: Bringing the Empire on Board 50 Smuts Goes In: The Rise of the Dominions 54 The Wilson-Smuts Synthesis 65 Wilson Undone 72 The Racial Equality Bill 84 IV: Conclusion 103 Bibliography 116 2 I: Introduction When President Woodrow Wilson left the United States for Europe at the end of 1918, he intended to create a new structure for international relations, based on a League of Nations, that would replace the pre-existing imperialist world structure with one based on national and racial (as was said at the time) self-determination. The results Wilson achieved by late April 1919, after several months of near-daily negotiation in Paris, varied between partial success and complete failure.1 Wilson had had other important goals in Paris, including establishing a framework for international arbitration of disputes, advancing labor rights, and promoting free trade and disarmament, and progress was made on all of these. But in terms of his own biography and the distinctive mission of U.S. foreign policy as he and other Americans understood it, the anti- imperial and pro-self-determination goals were paramount. -

Review of 142 Strand: a Radical Address in Victorian London & George Eliot in Germany,1854-55: 'Cherished Memories'

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The George Eliot Review English, Department of 2007 Review of 142 Strand: A Radical Address in Victorian London & George Eliot in Germany,1854-55: 'Cherished Memories' Rosemary Ashton Gerlinde Roder-Bolton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Ashton, Rosemary and Roder-Bolton, Gerlinde, "Review of 142 Strand: A Radical Address in Victorian London & George Eliot in Germany,1854-55: 'Cherished Memories'" (2007). The George Eliot Review. 522. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger/522 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George Eliot Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Rosemary Ashton, 142 Strand: A RadicalAddress in Victorian London (Chatto & Windus, 2006). pp. xiv + 386. ISBN 0 7011 7370 X Gerlinde Roder-Bolton, George Eliot in Germany,1854-55: 'Cherished Memories' (Ashgate, 2006). pp. xiii + 180. ISBN 0 7546 5054 5 The outlines of Marian Evans's life in the years immediately preceding her emergence as George Eliot are well-known-her work for the Westminster Review, her relationships with Chapman, Spencer and Lewes, and then her departure with the latter to Germany in July 1854. What these two studies do in their different ways is fill in the picture with fascinating detail. In focusing on the house that John Chapman rented from 1847 to 1854 and from which he ran the Westminster Review and his publishing business, Rosemary Ashton recreates the circle of radical intellectuals that the future novelist came into contact with through living there and working as the effective editor of Chapman' s journal. -

From Geology to Pathology -In Memoriam

BIBLIOGRAPHY Armstrong, Isobel, Tennyson in the 1850s: From Geology to Pathology - In Memoriam (1850) to Maud (1855)', in Tennyson: Seven Essays, ed. by Philip Collins (London: Macmillan, 1992), pp. 102-140 Atkinson, Henry George & Harriet Martineau, Letters on the Laws of Man's Nature and Development (London: John Chapman, 1851) Babbage, Charles, The Ninth Bridgewater Treatise. A Fragment (London: John Murray, 1837) Bailey, Edward, Charles Lyell (London: Thomas Nelson, 1962) Baker, Joseph Ellis, The Novel and the Oxford Movement (New York: Russell & Russell, 1932) Bakewell, Robert, An Introduction to Geology, Illustrative of the General Structure of the Earth; Comprising the Elements of the Science, and an Outline of the Geology and Mineral Geography of England (London: Harding, 1813) Barker, Juliet, The Brontes (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1994) Bartholomew, Michael, 'Lyell and Evolution: An Account of Lyell's Response to the Prospect of an Evolutionary Ancestry for Man', British Journal for the History of Science, 6 (1973), 261-303 —, The Non-Progress of Non-Progression: Two Responses to LyelPs Doctrine', The British Journal for the History of Science, 9 (1976), 166-174 —, The Singularity of Lyell', History of Science, 17 (1979), 276-293 Beer, Gillian, Darwin's Plots: Evolutionary Narrative in Darwin, George Eliot and Nineteenth-Century Fiction (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1983) Best, S., After Thoughts on Reading Dr. Buckland's Bridgewater Treatise (London: Hatchard, W. Mole; Salisbury: Brodie, 1837) Bowen, Desmond, The Idea of the Victorian Church; A Study of the Church of England 1833-1889 (Montreal: McGill University Press, 1968) Bowler, Peter J., The Invention of Progress; The Victorians and the Past (Oxford: Blackwell, 1989) —, Fossils and Progress; Paleontology and the Idea of Progressive Evolution in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Neale Watson Academic Publications, 1976) Brooke, John Hedley, The Natural Theology of the Geologists: Some Theological Strata', in Images of the Earth, Essays in the History of the Environmental Sciences ed. -

Curriculum Vitae Andrew Jackson O'shaughnessy

Curriculum Vitae Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy Personal Details Home Address: 308 E. Market Street, #305, Charlottesville, VA 22902. Work Address: Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. Post Office, Box 316 Charlottesville, Virginia 22902. E-Mail: [email protected] Telephone: wk. 434-984-7501. hm. 434-244-3541. Nationality: US and British (dual citizen). Education 1988: Oriel College, Oxford University. Doctor of Philosophy (D.Phil.) 1987: Oriel College, Oxford University. Modern History M.A. 1982 Oriel College, Oxford University. Modern History B.A. 1979: Columbia University, New York (School of General Studies). Professional Experience 2003 Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello. 2 • Fellowship program and seminars. • International and domestic conferences. • The Jefferson Library • Adult Enrichment Programs (outreach). • Publications. • Archaeology department • Research department • Documentary editing department of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. Retirement Series (published by Princeton University Press). Professor of American History, University of Virginia. 2002 Professor of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. 1998-03: Chair of the Department of History, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh. 1997 Associate Professor of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh (tenured). 1990-97: Assistant Professor (tenure-track) of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. 1989-90: Visiting Assistant Professor of American History, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas. 1988-89: Master, Eton College, Windsor, Berkshire. 1988: Teacher, The Forest School, London. 1987-90: Tutor for Davidson College (North Carolina), Summer Program in Eighteenth Century Studies, Wolfson College, Cambridge University. 1986-87: Lecturer, Lincoln College, Oxford University. -

2005. “On Edward Lombe, Translating Auguste Comte, and the Liberal English Press: a Previously Unpublished Letter.” Edited with an Introduction by Michael R

WELCOME! THIS FILE CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING MATERIAL: Martineau, Harriet. [1851] 2005. “On Edward Lombe, Translating Auguste Comte, and the Liberal English Press: A Previously Unpublished Letter.” Edited with an Introduction by Michael R. Hill. Sociological Origins 3 (Spring): 100-102. This digital file is furnished solely for private scholarly research under “fair use” provisions of copyright law. This file may not be published, posted on, or transmitted via the Internet or any other medium without the permission, as applicable, of the author(s), the publisher(s), and/or the creator of the file. This file and its contents Copyright © 2005 by the George Elliott Howard Institute for Advanced Sociological Research. This file was created by Michael R. Hill. For further information, contact: SOCIOLOGICAL ORIGINS, 2701 Sewell Street, Lincoln, Nebraska 68502 USA. SOCIOLOGICAL ORIGINS A JOURNAL OF RESEARCH DOCUMENTATION AND CRITIQUE ——————————— Volume 3, No. 2, Spring 2005 MICHAEL R. HILL, EDITOR The HMSS Special Issue: PROCEEDINGS OF THE 2002 HARRIET MARTINEAU SOCIOLOGICAL SOCIETY BICENTENNIAL SEMINAR IN AMBLESIDE _________________ A Documentary Symposium on Harriet Martineau On Edward Lombe, Translating Auguste Comte, and the Liberal English Press: A Previously Unpublished Letter Harriet Martineau Edited with an Introduction by Michael R. Hill ociologically speaking, Harriet Martineau wrote an important letter to one of her publishers, John Chapman, on 23 April 1851. Here, she announced her “notion” to Stranslate Auguste Comte’s Philosophie Positive. The end result was no small matter in the history of sociology: Martineau’s translation, underwritten by Edward Lombe and published by Chapman, effectively introduced Comte’s founding sociological treatise to large numbers of English-speaking readers for the first time in a comprehensive and detailed manner. -

Origins of the Myth of Social Darwinism: the Ambiguous Legacy of Richard Hofstadter’S Social Darwinism in American Thought

Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 71 (2009) 37–51 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jebo Origins of the myth of social Darwinism: The ambiguous legacy of Richard Hofstadter’s Social Darwinism in American Thought Thomas C. Leonard Department of Economics, Princeton University, Fisher Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544, United States article info abstract Article history: The term “social Darwinism” owes its currency and many of its connotations to Richard Received 19 February 2007 Hofstadter’s influential Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915 (SDAT). The post- Accepted 8 November 2007 SDAT meanings of “social Darwinism” are the product of an unresolved Whiggish tension in Available online 6 March 2009 SDAT: Hofstadter championed economic reform over free markets, but he also condemned biology in social science, this while many progressive social scientists surveyed in SDAT JEL classification: offered biological justifications for economic reform. As a consequence, there are, in effect, B15 B31 two Hofstadters in SDAT. The first (call him Hofstadter1) disparaged as “social Darwinism” B12 biological justification of laissez-faire, for this was, in his view, doubly wrong. The sec- ond Hofstadter (call him Hofstadter2) documented, however incompletely, the underside Keywords: of progressive reform: racism, eugenics and imperialism, and even devised a term for it, Social Darwinism “Darwinian collectivism.” This essay documents and explains Hofstadter’s ambivalence in Evolution SDAT, especially where, as with Progressive Era eugenics, the “two Hofstadters” were at odds Progressive Era economics Malthus with each other. It explores the historiographic and semantic consequences of Hofstadter’s ambivalence, including its connection with the Left’s longstanding mistrust of Darwinism as apology for Malthusian political economy. -

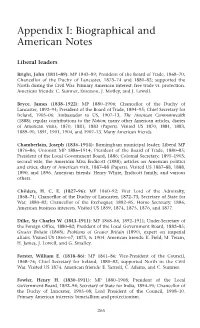

Appendix I: Biographical and American Notes

Appendix I: Biographical and American Notes Liberal leaders Bright, John (1811–89): MP 1843–89; President of the Board of Trade, 1868–70; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1873–74 and 1880–82; supported the North during the Civil War. Primary American interest: free trade vs. protection. American friends: C. Sumner, Emerson, J. Motley, and J. Lowell. Bryce, James (1838–1922): MP 1880–1906; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1892–94; President of the Board of Trade, 1894–95; Chief Secretary for Ireland, 1905–06; Ambassador to US, 1907–13; The American Commonwealth (1888); regular contributions to the Nation; many other American articles, diaries of American visits, 1870, 1881, 1883 (Papers). Visited US 1870, 1881, 1883, 1889–90, 1891, 1901, 1904, and 1907–13. Many American friends. Chamberlain, Joseph (1836–1914): Birmingham municipal leader; Liberal MP 1876–86; Unionist MP 1886–1914; President of the Board of Trade, 1880–85; President of the Local Government Board, 1886; Colonial Secretary, 1895–1903; second wife, the American Miss Endicott (1888); articles on American politics and cities; diary of American visit, 1887–88 (Papers). Visited US 1887–88, 1888, 1890, and 1896. American friends: Henry White, Endicott family, and various others. Childers, H. C. E. (1827–96): MP 1860–92; First Lord of the Admiralty, 1868–71; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1872–73; Secretary of State for War, 1880–82; Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1882–85; Home Secretary, 1886; American business interests. Visited US 1859, 1874, 1875, 1876, and 1877. Dilke, Sir Charles W. (1843–1911): MP 1868–86, 1892–1911; Under-Secretary of the Foreign Office, 1880–82; President of the Local Government Board, 1882–85; Greater Britain (1868); Problems of Greater Britain (1890); expert on imperial affairs. -

The Development and Early Research Results of Mill Marginalia Online

ILCEA Revue de l’Institut des langues et cultures d'Europe, Amérique, Afrique, Asie et Australie 39 | 2020 Les humanités numériques dans une perspective internationale : opportunités, défis, outils et méthodes Handwritten Marginalia and Digital Search: The Development and Early Research Results of Mill Marginalia Online Marginalia manuscrits et recherche numérique : développement et résultats préliminaires de l’édition en ligne de Mill Marginalia. Albert D. Pionke Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ilcea/8582 DOI: 10.4000/ilcea.8582 ISSN: 2101-0609 Publisher UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Printed version ISBN: 978-2-37747-174-4 ISSN: 1639-6073 Electronic reference Albert D. Pionke, « Handwritten Marginalia and Digital Search: The Development and Early Research Results of Mill Marginalia Online », ILCEA [Online], 39 | 2020, Online since 03 March 2020, connection on 10 October 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ilcea/8582 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ ilcea.8582 This text was automatically generated on 10 October 2020. © ILCEA Handwritten Marginalia and Digital Search: The Development and Early Research... 1 Handwritten Marginalia and Digital Search: The Development and Early Research Results of Mill Marginalia Online Marginalia manuscrits et recherche numérique : développement et résultats préliminaires de l’édition en ligne de Mill Marginalia. Albert D. Pionke 1 Victorian Britain’s leading philosophical empiricist and liberal theorist—and, perhaps the dominant figure in Victorian intellectual life from the 1860s, when he was elected to Parliament as Liberal Member for Westminster, through the 1880s, the decade after his death in which intellectuals in a variety of fields continued to define themselves with respect to his legacy—John Stuart Mill authored significant works on logic, epistemology, political economy, aesthetics, and social reform. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 13 June 2014 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Zon, Bennett (2013) 'The music of non-Western nations and the evolution of British ethnomusicology.', in Cambridge history of world music. , pp. 298-318. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139029476.017 Publisher's copyright statement: c Cambridge University Press 2013. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk The Music of Non-Western Nations and the Evolution of British Ethnomusicology According to Philip Bohlman, ‘national music reflects the image of the nation so that those living in the nation recognize themselves in basic but crucial ways. It is music conceived in the image of the nation that is created through efforts to represent something quintessential about the nation.’1 Like all nations, Britain conceived of music in its own image, whether indigenous or foreign, and whilst the British Empire expanded from the seventeenth century onwards, so too did the characterization of its own, and the world’s, national music.