Hurrell Froude and the Development of His Ideal of the Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testament of Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 P.461

Testament of Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 p.461 Thomas Carlyle SC70/6/21 [page 461] I, Thomas Carlyle of 5 Great Cheyne Row, Chelsea in the County of Middlesex Esquire declare this to be my last Will and Testament Revoking all former Will I direct all my just debts, funeral and testamentary expences to be paid as soon as may be after my decease And it is my express instruction that since I cannot be laid in the Grave at Haddington I shall be placed beside my Father and Mother in the Churchyard of Ecclefechan. I appoint my Brother John Aitken Carlyle, Doctor of Medicine and my friend John Foster of Palace Gate House, Kensington, Esquire Executors and Trustees of this my Will. If my said Brother should die in my lifetime I appoint my Brother James Carlyle to be an Executor and Trustee in his stead and if the said John Forster should die in my [p.463] my lifetime I appoint my friend James Anthony Froude to be an Executor and Trustee in his stead. I give to my dear and ever helpful Brother John A. Carlyle my Leasehold messuage in Great Cheyne Row in which I reside subject to the rent and covenants under which I hold the same and all such of my Furniture plate linen china books prints pictures and other effects therein as are not hereinafter bequeathed specifically My Brother John has no need of my money or help and therefore in addition to this small remembrance I bequeath to him only the charge of being Executor of my Will and of seeing everything peaceably fulfilled If he survives me as is natural he will not refuse My poor and indeed almost pathetic collection of books (with the exception of those hereinafter specifically given) I request him to accept as a memento of me while he stays behind I give my Watch to my Nephew Thomas the son of my Brother Alexander "Alicks Tom" as a Memorial of the affection I have for him and of my thankful (and also hopeful) approval of all that I have ever got to know or surmise about him. -

Arguing with the Coloniser: Linguistic Strategies in John Jacob Thomas's Froudacity (1889) 1

151 JANA GOHRISCH Arguing with the Coloniser: Linguistic Strategies in John Jacob Thomas's Froudacity (1889) 1. Introduction In the West Indies there is indefinite wealth waiting to be developed by intelligence and capital; and men with such resources, both English and American, might be tempted still to settle there, and lead the blacks along with them into more settled manners and higher forms of civilisation. But the future of the blacks, and our own influence over them for good, depend on their being protected from themselves and from the schemers who would take advantage of them. […] As it has been in Hayti, so it must be in Trinidad if the Eng- lish leave the blacks to be their own masters. […] [T]he keener-witted Trinidad blacks are watching as eagerly as we do the development of the Irish problem. They see the identity of the situation. (Froude 1888, 79; 86; 87) Anyhow, Mr. Froude's history of the Emancipation may here be amended for him by a reminder that, in the British Colonies, it was not Whites as masters, and Blacks as slaves, who were affected by that momentous measure. In fact, 1838 found in the British Colonies very nearly as many Negro and Mulatto slave-owners as there were white. Well then, these black and yellow planters received their quota, it may be presumed, of the £ 20,000,000 sterling indemnity. They were part and parcel of the proprietary body in the Colonies, and had to meet the crisis like the rest. They were very wealthy, some of these Ethiopic accomplices of the oppressors of their own race. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

1 the Wilson-Smuts Synthesis: Racial Self

The Wilson-Smuts Synthesis: Racial Self-Determination and the Institutionalization of World Order A thesis submitted by Scott L. Malcomson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations Tufts University Fletcher School of International Law and Diplomacy January 2020 Adviser: Jeffrey W. Taliaferro ©2019, Scott L. Malcomson 1 Table of Contents I: Introduction 3 II: Two Paths to Paris. Jan Smuts 8 Woodrow Wilson 26 The Paths Converge 37 III: Versailles. Wilson Stays Out: Isolation and Neutrality 43 Lloyd George: Bringing the Empire on Board 50 Smuts Goes In: The Rise of the Dominions 54 The Wilson-Smuts Synthesis 65 Wilson Undone 72 The Racial Equality Bill 84 IV: Conclusion 103 Bibliography 116 2 I: Introduction When President Woodrow Wilson left the United States for Europe at the end of 1918, he intended to create a new structure for international relations, based on a League of Nations, that would replace the pre-existing imperialist world structure with one based on national and racial (as was said at the time) self-determination. The results Wilson achieved by late April 1919, after several months of near-daily negotiation in Paris, varied between partial success and complete failure.1 Wilson had had other important goals in Paris, including establishing a framework for international arbitration of disputes, advancing labor rights, and promoting free trade and disarmament, and progress was made on all of these. But in terms of his own biography and the distinctive mission of U.S. foreign policy as he and other Americans understood it, the anti- imperial and pro-self-determination goals were paramount. -

The Tractarians' Political Rhetoric

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar English Faculty Research English 9-2008 The rT actarians' Political Rhetoric Robert Ellison Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/english_faculty Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Ellison, Robert H. “The rT actarians’ Political Rhetoric.” Anglican and Episcopal History 77.3 (September 2008): 221-256. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “The Tractarians’ Political Rhetoric”1 Robert H. Ellison Published in Anglican and Episcopal History 77.3 (September 2008): 221-256 On Sunday 14 July 1833, John Keble, Professor of Poetry at the University of Oxford,2 preached a sermon entitled “National Apostasy” in the Church of St Mary the Virgin, the primary venue for academic sermons, religious lectures, and other expressions of the university’s spiritual life. The sermon is remembered now largely because John Henry Newman, who was vicar of St Mary’s at the time,3 regarded it as the beginning of the Oxford Movement. Generally regarded as stretching from 1833 to Newman’s conversion to Rome in 1845, the movement was an effort to return the Church of England to her historic roots, as expressed in 1 Work on this essay was made possible by East Texas Baptist University’s Faculty Research Grant program and the Jim and Ethel Dickson Research and Study Endowment. -

Lancelot Andrewes' Doctrine of the Incarnation

Lancelot Andrewes’ Doctrine of the Incarnation Respectfully Submitted to the Faculty of Nashotah House In Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Theological Studies Davidson R. Morse Nashotah House May 2003 1 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the whole faculty of Nashotah House Seminary for the care and encouragement I received while researching and writing this thesis. Greatest thanks, however, goes to the Rev. Dr. Charles Henery, who directed and edited the work. His encyclopedic knowledge of the theology and literature of the Anglican tradition are both formidable and inspirational. I count him not only a mentor, but also a friend. Thanks also goes to the Rev. Dr. Tom Holtzen for his guidance in my research on the Christological controversies and points of Patristic theology. Finally, I could not have written the thesis without the love and support of my wife. Not only did she manage the house and children alone, but also she graciously encouraged me to pursue and complete the thesis. I dedicate it to her. Rev. Davidson R. Morse Easter Term, 2003 2 O Lord and Father, our King and God, by whose grace the Church was enriched by the great learning and eloquent preaching of thy servant Lancelot Andrewes, but even more by his example of biblical and liturgical prayer: Conform our lives, like his, we beseech thee, to the image of Christ, that our hearts may love thee, our minds serve thee, and our lips proclaim the greatness of thy mercy; through the same Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. -

The Oxford Architectural and Historical Society and the Oxford Movement

The Oxford Architectural and Historical Society and the Oxford Movement By S. L. OLLARD (Read before the Society, 31 May, 1939) y the Oxford Movement I understand the religious revival which began B with John Keble's sermon on National Apostasy preached in St. Mary's on 14 July, 1833. The strictly Oxford stage of that Movement, its first chapter, ended in 1845 with the degradation of W. G. Ward in February and the secession to Rome of Mr. Newman and his friends at Littlemore in the following October. I am not very much concerned in this paper with the story after that date, though I have pursued it in the printed reports and other sources up to 1852. The Oxford Movement was at base a moral movement. The effect of 18th century speculation and of the French Revolution had been to force men's minds back to first principles. Reform had begun. In England it had shaken the foundations of the existing parliamentary system, and the Church itself seemed in danger of being reformed away. Some of its supposed safeguards, e.g., the penal laws against Nonconformists and Roman Catholics, had been removed, yet abuses, pluralism and non-residence for instance, remained ob vious weaknesses. Meanwhile, most of its official defenders were not armed with particularly spiritual weapons. The men of the Oxford Movement were con vinced of a great truth, namely that the English Church was a living part of the one Holy Catholic Church: that it was no state-created body, but part of the Society founded by the Lord Himself with supernatural powers and super natural claims. -

Isaac Williams (1802-1865), the Oxford Movement and the High Churchmen: a Study of His Theological and Devotional Writings

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Isaac Williams (1802-1865), the Oxford Movement and the High Churchmen: A Study of his Theological and Devotional Writings. Boneham, John Award date: 2009 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 Isaac Williams (1802-1865), the Oxford Movement and the High Churchmen: A Study of his Theological and Devotional Writings. By, John Boneham, B.D. (hons.), M.Th. Ph.D., Bangor University (2009) Summary Isaac Williams was one of the leading members of the Oxford Movement during the 1830-60s and made a valuable contribution to the movement through his published poetry, tracts, sermons and biblical commentaries which were written to help propagate Tractarian principles. Although he was active in Oxford as a tutor of Trinity College during the 1830s, Williams left Oxford in 1842 after failing to be elected to the university’s chair of poetry. -

Curriculum Vitae Andrew Jackson O'shaughnessy

Curriculum Vitae Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy Personal Details Home Address: 308 E. Market Street, #305, Charlottesville, VA 22902. Work Address: Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. Post Office, Box 316 Charlottesville, Virginia 22902. E-Mail: [email protected] Telephone: wk. 434-984-7501. hm. 434-244-3541. Nationality: US and British (dual citizen). Education 1988: Oriel College, Oxford University. Doctor of Philosophy (D.Phil.) 1987: Oriel College, Oxford University. Modern History M.A. 1982 Oriel College, Oxford University. Modern History B.A. 1979: Columbia University, New York (School of General Studies). Professional Experience 2003 Vice President of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello. 2 • Fellowship program and seminars. • International and domestic conferences. • The Jefferson Library • Adult Enrichment Programs (outreach). • Publications. • Archaeology department • Research department • Documentary editing department of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. Retirement Series (published by Princeton University Press). Professor of American History, University of Virginia. 2002 Professor of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. 1998-03: Chair of the Department of History, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh. 1997 Associate Professor of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh (tenured). 1990-97: Assistant Professor (tenure-track) of American History, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. 1989-90: Visiting Assistant Professor of American History, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas. 1988-89: Master, Eton College, Windsor, Berkshire. 1988: Teacher, The Forest School, London. 1987-90: Tutor for Davidson College (North Carolina), Summer Program in Eighteenth Century Studies, Wolfson College, Cambridge University. 1986-87: Lecturer, Lincoln College, Oxford University. -

Lancelot Andrewes' Life And

LANCELOT ANDREWES’ LIFE AND MINISTRY A FOUNDATION FOR TRADITIONAL ANGLICAN PRIESTS by Orville Michael Cawthon, Sr. B.B.A, Georgia State University, 1983 A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religion at Reformed Theological Seminary Charlotte, North Carolina September 2014 Accepted: Thesis Advisor ______________________________ Donald Fortson, Ph.D. ii ABSTRACT Lancelot Andrewes Life and Ministry A Foundation for Traditional Anglican Priest Orville Michael Cawthon, Sr. This thesis explores Lancelot Andrewes’ life and ministry as an example for Traditional Anglican Priests. An introduction and biography are presented, followed by an examination of his prayer life, doctrine, and liturgy. His prayer life is examined through his private prayers, via tract number 88 of the Tracts for the Times, daily prayers, and sermons. The second evaluation made is of Andrewes’ doctrine. A review of his catechism is followed by his teaching of the Commandments. His sermons are examined and demonstrate his desire and ability to link the Old Testament and the New Testament through Jesus Christ and a review is made through examining his sermons for the different church seasons. Thirdly, Andrewes’ liturgy is the focus, as many of his practices are still used today within the Traditional Anglican Church. His desire for holiness and beauty as reflected in his Liturgy is seen, as well as his position on what should be allowed in the worship of God. His love for the Eucharist is examined as he defends the English Church’s use of the term “Real Presence” in its relationship to the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist. -

Evangelicals and Tractarians: Then and Now PETERTOON Ln 1967 and in 1977 Evangelical Anglicans Held National Conferences at Keele and Nottingham

Evangelicals and Tractarians: then and now PETERTOON ln 1967 and in 1977 evangelical Anglicans held national conferences at Keele and Nottingham. On each occasion a statement was issued: Keele '67 and Nottingham '77. There were basically contemporary confessions of faith and practice. In 1978 Anglo-Catholics held a national conference at Loughborough but this produced no statement. It is hoped that such a document will be produced by a follow-up conference projected for the future. According to John Henry Newman, who moved from evangelical ism to Tractarianism to Roman Catholicism, the Tractarian Move ment began on 14 July 1833 when his friend John Keble preached the assize sermon in the university pulpit of Oxford. It was publ.shed as National Apostasy. Probably it is more accurate to state that Tract arianism began when Newman began to write and distribute the Tracts for the Times in September 1833. It represented a develop ment (or some would say, corruption) of traditional high-church principles and doctrines. The dating of the origin of evangelicalism is more difficult. Some would want to trace it to the Reformation of the sixteenth century but it is more realistic to trace it to the Evangelical Revival of the eighteenth century. In this revival we have the beginnings of the parish (as opposed to itinerant) ministries of clergy of evangelical convictions-William Romaine of London, for example. Therefore, when Tractarianism appeared in the English Church, evangelicalism was producing a third generation of clergy and laity. Not a few of the leading Tractarians had enjoyed an evangelical upbringing.1 It is an interesting question as to whether it may be claimed that Tractarianism is the true or the logical climax of Anglican evangel icalism. -

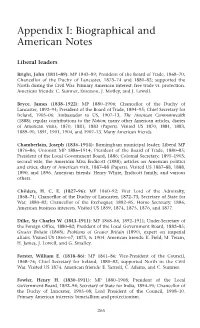

Appendix I: Biographical and American Notes

Appendix I: Biographical and American Notes Liberal leaders Bright, John (1811–89): MP 1843–89; President of the Board of Trade, 1868–70; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1873–74 and 1880–82; supported the North during the Civil War. Primary American interest: free trade vs. protection. American friends: C. Sumner, Emerson, J. Motley, and J. Lowell. Bryce, James (1838–1922): MP 1880–1906; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1892–94; President of the Board of Trade, 1894–95; Chief Secretary for Ireland, 1905–06; Ambassador to US, 1907–13; The American Commonwealth (1888); regular contributions to the Nation; many other American articles, diaries of American visits, 1870, 1881, 1883 (Papers). Visited US 1870, 1881, 1883, 1889–90, 1891, 1901, 1904, and 1907–13. Many American friends. Chamberlain, Joseph (1836–1914): Birmingham municipal leader; Liberal MP 1876–86; Unionist MP 1886–1914; President of the Board of Trade, 1880–85; President of the Local Government Board, 1886; Colonial Secretary, 1895–1903; second wife, the American Miss Endicott (1888); articles on American politics and cities; diary of American visit, 1887–88 (Papers). Visited US 1887–88, 1888, 1890, and 1896. American friends: Henry White, Endicott family, and various others. Childers, H. C. E. (1827–96): MP 1860–92; First Lord of the Admiralty, 1868–71; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1872–73; Secretary of State for War, 1880–82; Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1882–85; Home Secretary, 1886; American business interests. Visited US 1859, 1874, 1875, 1876, and 1877. Dilke, Sir Charles W. (1843–1911): MP 1868–86, 1892–1911; Under-Secretary of the Foreign Office, 1880–82; President of the Local Government Board, 1882–85; Greater Britain (1868); Problems of Greater Britain (1890); expert on imperial affairs.