Trinity College Cambridge 2 November 2014 a (VERY BRIEF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tractarians' Political Rhetoric

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar English Faculty Research English 9-2008 The rT actarians' Political Rhetoric Robert Ellison Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/english_faculty Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Ellison, Robert H. “The rT actarians’ Political Rhetoric.” Anglican and Episcopal History 77.3 (September 2008): 221-256. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “The Tractarians’ Political Rhetoric”1 Robert H. Ellison Published in Anglican and Episcopal History 77.3 (September 2008): 221-256 On Sunday 14 July 1833, John Keble, Professor of Poetry at the University of Oxford,2 preached a sermon entitled “National Apostasy” in the Church of St Mary the Virgin, the primary venue for academic sermons, religious lectures, and other expressions of the university’s spiritual life. The sermon is remembered now largely because John Henry Newman, who was vicar of St Mary’s at the time,3 regarded it as the beginning of the Oxford Movement. Generally regarded as stretching from 1833 to Newman’s conversion to Rome in 1845, the movement was an effort to return the Church of England to her historic roots, as expressed in 1 Work on this essay was made possible by East Texas Baptist University’s Faculty Research Grant program and the Jim and Ethel Dickson Research and Study Endowment. -

The Tractarians: a Study of the Interaction of John Keble, Hurrell Froude, John Henry Newman, and Edward Pusey in the Genesis and Early Course of the Oxford Movement

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 6-1-1965 The tractarians: A study of the interaction of John Keble, Hurrell Froude, John Henry Newman, and Edward Pusey in the genesis and early course of the Oxford movement Andrew C. Conway University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Conway, Andrew C., "The tractarians: A study of the interaction of John Keble, Hurrell Froude, John Henry Newman, and Edward Pusey in the genesis and early course of the Oxford movement" (1965). Student Work. 355. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/355 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TftACTAItXAIfS A 3m m OF THE IMSRACTXOI? OF JOHH KBBJUE, HOBEKOi f r o t o e , jo h h mmnr m m m 9 km edwako pusey x i the g&me&zs AMD EARJMC COURSE OF TUB OXFORD HOVEMIST A T h e s is t o t h e Department of History and th e Faculty of the College of Graduate Studies University of Omaha Xn Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Hester of Arts t y Andrew C# Conway June 1 9 4 5 UMI Number: EP72993 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Lancelot Andrewes' Doctrine of the Incarnation

Lancelot Andrewes’ Doctrine of the Incarnation Respectfully Submitted to the Faculty of Nashotah House In Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Theological Studies Davidson R. Morse Nashotah House May 2003 1 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the whole faculty of Nashotah House Seminary for the care and encouragement I received while researching and writing this thesis. Greatest thanks, however, goes to the Rev. Dr. Charles Henery, who directed and edited the work. His encyclopedic knowledge of the theology and literature of the Anglican tradition are both formidable and inspirational. I count him not only a mentor, but also a friend. Thanks also goes to the Rev. Dr. Tom Holtzen for his guidance in my research on the Christological controversies and points of Patristic theology. Finally, I could not have written the thesis without the love and support of my wife. Not only did she manage the house and children alone, but also she graciously encouraged me to pursue and complete the thesis. I dedicate it to her. Rev. Davidson R. Morse Easter Term, 2003 2 O Lord and Father, our King and God, by whose grace the Church was enriched by the great learning and eloquent preaching of thy servant Lancelot Andrewes, but even more by his example of biblical and liturgical prayer: Conform our lives, like his, we beseech thee, to the image of Christ, that our hearts may love thee, our minds serve thee, and our lips proclaim the greatness of thy mercy; through the same Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. -

Guide to the Archives (Pdf)

Welcome to Keble College Archives Guide to the Archives The Holdings Keble College was founded in 1870 in memory of John Keble (1792-1866), a founding member of the Tractarian movement, also known as the Oxford Movement, which sought to recover the Catholic heritage of the Church of England. Whilst relatively young by Oxford standards, the College’s history and importance should not be underestimated. Its archival holdings bear witness to changes in the College, the University and in British society. The Archives are a rich resource for research, especially for current students. For those reading History, English or Theology, the Archives could be a fount of valuable primary source material. Among the records of Keble College held here are: Minutes of the meetings of the College Council from 1870 to 1950 College accounts and ledgers Historical material on the advowsons of which Keble College is the patron Records of JCR sports clubs and societies Architectural records, including the original designs by the architect William Butterfield Personal papers and memorabilia of key members of the Oxford Movement, including Canon H. P. Liddon and Dr E. B. Pusey Personal papers and memorabilia of members of the College. One collection of international importance held at Keble College is that relating to John Keble, father of the Oxford Movement. The material held here includes: Keble’s manuscripts of poems that became The Christian Year Correspondence between John Keble and his family, friends and associates, in particular, with John Henry Newman, 1829-1863. The Special Collections in Keble College Library also holds John Keble’s own personal library. -

The Oxford Architectural and Historical Society and the Oxford Movement

The Oxford Architectural and Historical Society and the Oxford Movement By S. L. OLLARD (Read before the Society, 31 May, 1939) y the Oxford Movement I understand the religious revival which began B with John Keble's sermon on National Apostasy preached in St. Mary's on 14 July, 1833. The strictly Oxford stage of that Movement, its first chapter, ended in 1845 with the degradation of W. G. Ward in February and the secession to Rome of Mr. Newman and his friends at Littlemore in the following October. I am not very much concerned in this paper with the story after that date, though I have pursued it in the printed reports and other sources up to 1852. The Oxford Movement was at base a moral movement. The effect of 18th century speculation and of the French Revolution had been to force men's minds back to first principles. Reform had begun. In England it had shaken the foundations of the existing parliamentary system, and the Church itself seemed in danger of being reformed away. Some of its supposed safeguards, e.g., the penal laws against Nonconformists and Roman Catholics, had been removed, yet abuses, pluralism and non-residence for instance, remained ob vious weaknesses. Meanwhile, most of its official defenders were not armed with particularly spiritual weapons. The men of the Oxford Movement were con vinced of a great truth, namely that the English Church was a living part of the one Holy Catholic Church: that it was no state-created body, but part of the Society founded by the Lord Himself with supernatural powers and super natural claims. -

Isaac Williams (1802-1865), the Oxford Movement and the High Churchmen: a Study of His Theological and Devotional Writings

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Isaac Williams (1802-1865), the Oxford Movement and the High Churchmen: A Study of his Theological and Devotional Writings. Boneham, John Award date: 2009 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 Isaac Williams (1802-1865), the Oxford Movement and the High Churchmen: A Study of his Theological and Devotional Writings. By, John Boneham, B.D. (hons.), M.Th. Ph.D., Bangor University (2009) Summary Isaac Williams was one of the leading members of the Oxford Movement during the 1830-60s and made a valuable contribution to the movement through his published poetry, tracts, sermons and biblical commentaries which were written to help propagate Tractarian principles. Although he was active in Oxford as a tutor of Trinity College during the 1830s, Williams left Oxford in 1842 after failing to be elected to the university’s chair of poetry. -

Lancelot Andrewes' Life And

LANCELOT ANDREWES’ LIFE AND MINISTRY A FOUNDATION FOR TRADITIONAL ANGLICAN PRIESTS by Orville Michael Cawthon, Sr. B.B.A, Georgia State University, 1983 A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religion at Reformed Theological Seminary Charlotte, North Carolina September 2014 Accepted: Thesis Advisor ______________________________ Donald Fortson, Ph.D. ii ABSTRACT Lancelot Andrewes Life and Ministry A Foundation for Traditional Anglican Priest Orville Michael Cawthon, Sr. This thesis explores Lancelot Andrewes’ life and ministry as an example for Traditional Anglican Priests. An introduction and biography are presented, followed by an examination of his prayer life, doctrine, and liturgy. His prayer life is examined through his private prayers, via tract number 88 of the Tracts for the Times, daily prayers, and sermons. The second evaluation made is of Andrewes’ doctrine. A review of his catechism is followed by his teaching of the Commandments. His sermons are examined and demonstrate his desire and ability to link the Old Testament and the New Testament through Jesus Christ and a review is made through examining his sermons for the different church seasons. Thirdly, Andrewes’ liturgy is the focus, as many of his practices are still used today within the Traditional Anglican Church. His desire for holiness and beauty as reflected in his Liturgy is seen, as well as his position on what should be allowed in the worship of God. His love for the Eucharist is examined as he defends the English Church’s use of the term “Real Presence” in its relationship to the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist. -

Evangelicals and Tractarians: Then and Now PETERTOON Ln 1967 and in 1977 Evangelical Anglicans Held National Conferences at Keele and Nottingham

Evangelicals and Tractarians: then and now PETERTOON ln 1967 and in 1977 evangelical Anglicans held national conferences at Keele and Nottingham. On each occasion a statement was issued: Keele '67 and Nottingham '77. There were basically contemporary confessions of faith and practice. In 1978 Anglo-Catholics held a national conference at Loughborough but this produced no statement. It is hoped that such a document will be produced by a follow-up conference projected for the future. According to John Henry Newman, who moved from evangelical ism to Tractarianism to Roman Catholicism, the Tractarian Move ment began on 14 July 1833 when his friend John Keble preached the assize sermon in the university pulpit of Oxford. It was publ.shed as National Apostasy. Probably it is more accurate to state that Tract arianism began when Newman began to write and distribute the Tracts for the Times in September 1833. It represented a develop ment (or some would say, corruption) of traditional high-church principles and doctrines. The dating of the origin of evangelicalism is more difficult. Some would want to trace it to the Reformation of the sixteenth century but it is more realistic to trace it to the Evangelical Revival of the eighteenth century. In this revival we have the beginnings of the parish (as opposed to itinerant) ministries of clergy of evangelical convictions-William Romaine of London, for example. Therefore, when Tractarianism appeared in the English Church, evangelicalism was producing a third generation of clergy and laity. Not a few of the leading Tractarians had enjoyed an evangelical upbringing.1 It is an interesting question as to whether it may be claimed that Tractarianism is the true or the logical climax of Anglican evangel icalism. -

Article Review Towards a Richer Appreciation of the Oxford Movement

ecclesiology 16 (2020) 243-253 ECCLESIOLOGY brill.com/ecso Article Review ∵ Towards a Richer Appreciation of the Oxford Movement Paul Avis Durham University, Durham, UK, and University of Exeter, Exeter, UK [email protected] Stewart J. Brown, Peter B. Nockles and James Pereiro (eds), (2017) The Oxford Handbook of the Oxford Movement. Oxford: Oxford University Press. xx + 646 pages, isbn 978-0-19-958018-7 (hbk), £95.00. To read The Oxford Handbook of the Oxford Movement more or less from cover to cover has been a hugely rewarding experience, even though I am no stranger to its subject matter – the history and writings of the movement that cam- paigned to revive a catholic theology, practice and sensibility within the Church of England in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. In engag- ing with this book I am, in a sense, coming home. John Keble’s parochial ministry, John Henry Newman’s epistemology and ecclesiology, and Edward Bouverie Pusey’s sacramental and ecumenical theology have been deeply for- mative for me. And that is the spirit (or ethos in Tractarian-speak, as James Pereiro has shown)1 in which I approach this estimable example of the Oxford Handbook genre. The Oxford (or Tractarian) Movement was a creative upsurge of theological, pastoral and liturgical renewal which lasted from its arresting beginning with John Keble’s Assize Sermon and the first Tracts for the Times in 1833 to John 1 James Pereiro, ‘Ethos’ and the Oxford Movement: At the Heart of Tractarianism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). © paul avis, 2020 | doi:10.1163/17455316-01602007 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the cc by 4.0Downloaded License. -

A Memoir of the Rev. John Keble

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com #, w is* OF THE REV. JOHN KEBLE, M.A. LATE VICAR OF HURSLEY. BY THE RIGHT HON. SIR J. T. COLERIDGE, D.C.L. " Te mihi junxerunt nivei sine crimine mores, Simplicitasque sagax, ingenuusque pudor ; Et bene nota fides, et candor frontis honestae, Et studia a studiis non aliena meis." Joannes Secundus. VOL. II. SecotrtJ lEtritton, With Corrections and Additions. C.0XF0BD and LONDON i JAMES PARKER AND CO. 1869. All Rights reserved. - »> t'Cl. t /Si <!, r< • . v CONTENTS.— ♦ VOL. II. CHAPTER XIII. PACK Otterboume Church and Parsonage. — Ampfield Church and Par sonage. — Hursley Parsonage. — " Lyra Innocentium." — Keble's Resolution as to the English Church. — " Mother out of Sight." 279 CHAPTER XIV. 'Lyra Innocentium." — Charles Marriott's College. — Gladstone Contests . 319 CHAPTER XV. Should Keble have been preferred to Dignity in the Church ? — Tour in Wales, and Visit to Ireland, 1840. — Tour in Scotland, 1842. — Undertakes to Write Life of Bishop Wilson. — Visit to Isle of Man, 1849. — Marriages with Sister of Deceased Wife, 1849.— Second Visit to Man, 1852.— Trip to Skye, 1853 . 350 CHAPTER XVI. Death of W. C. Yonge, 1854. — Oxford University Reform . .377 CHAPTER XVII. 1854, Bishop of New Zealand at Hursley. — Francis George Cole ridge's Death.— Visit to the West. — The Vineyard and Dart- ington Rectory. — Archdeacon Wilberforce. — Service for Emi grants. — North of Devon. — Professor Reed. — Decision of the Denison Case. -

CORPORATE REUNION: a NINETEENTH- CENTURY DILEMMA VINCENT ALAN Mcclelland University of Hull

CORPORATE REUNION: A NINETEENTH- CENTURY DILEMMA VINCENT ALAN McCLELLAND University of Hull EFORE THE ADVENT of the Oxford Movement in 1833 and before the B young converts George Spencer and Ambrose Phillipps had, shortly before his death, enlisted the powerful support and encouragement of the aristocratic Louis de Quelin, Archbishop of Paris,1 in the establishment in 1838 of an Association of Prayers for the Conversion of England, the matter of the reunion of a divided Christendom had greatly engaged the attention of Anglican divines. Indeed, as Brandreth in his study of the ecumenical ideals of the Oxford Movement has pointed out, "there is scarcely a generation [in the history of the Church of England] from the time of the Reformation to our own day which has not caught, whether perfectly or imperfectly, the vision of a united Christendom."2 The most learned of Jacobean divines, Lancelot Andrewes, Bishop of Winchester under James I, regularly interceded "for the Universal Church, its confir mation and growth; for the Western Church, its restoration and pacifi cation; for the Church of Great Britain, the setting in order of the things that are wanting in it and the strengthening of the things that remain".3 In the anxiety to locate the needs of the national church within the context of the Church Universal, Andrewes was followed by a host of Carolingian divines and Settlement nonjurors, themselves the harbingers of that Anglo-Catholic spirit which gave life, albeit by means of a prolonged and painful Caesarian section, to the vibrant Tractarian quest for ecclesial justification. -

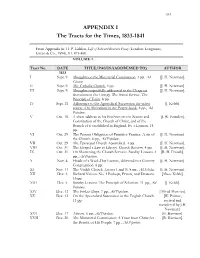

APPENDIX I the Tracts for the Times, 1833-1841

334 APPENDIX I The Tracts for the Times, 1833-1841 From Appendix in: H. P. Liddon, Life of Edward Bouverie Pusey (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1894), III: 473-480. VOLUME I Tract No. DATE TITLE/PAGES/(ADDRESSED TO) AUTHOR 1833 I Sept. 9. Thoughts on the Ministerial Commission. 4 pp. Ad [J. H. Newman]. Clerum II Sept. 9. The Catholic Church. 4 pp. [J. H. Newman]. III Sept. 9. Thoughts respectfully addressed to the Clergy on [J. H. Newman]. alterations in the Liturgy. The Burial Service. The Principle of Unity. 8 pp. IV Sept. 21. Adherence to the Apostolical Succession the safest [J. Keble]. course. On Alterations in the Prayer-book. 8 pp., Ad Populum. V Oct. 18. A short address to his Brethren on the Nature and [J. W. Bowden]. Constitution of the Church of Christ, and of the Branch of it established in England. By a Layman. 15. pp. VI Oct. 29. The Present Obligation of Primitive Practice. A sin of [J. H. Newman]. the Church. 4 pp., Ad Populum. VII Oct. 29. The Episcopal Church Apostolical. 4 pp. [J. H. Newman]. VIII Oct. 31. The Gospel a Law of Liberty. Church Reform. 4 pp. [J. H. Newman]. IX Oct. 31. On Shortening the Church Services. Sunday Lessons. 4 [R. H. Froude]. pp., Ad Populum. X Nov. 4. Heads of a Week-Day Lecture, delivered to a Country [J. H. Newman]. Congregation. 6 pp. XI Nov. 11. The Visible Church. Letters I and II. 8 pp., Ad Scholas. [J. H. Newman]. XII Dec. 4. Richard Nelson. No. 1 Bishops, Priests, and Deacons.