BMH.WS1041.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1798) the Pockets of Our Great-Coats Full of Barley (No Kitchens on the Run, No Striking Camp) We Moved Quick and Sudden in Our Own Country

R..6~t6M FOR.. nt6 tR..tSH- R..6lS6LS (Wexford, 1798) The pockets of our great-coats full of barley (No kitchens on the run, no striking camp) We moved quick and sudden in our own country. The priest lay behind ditches with the tramp. A people, hardly marching - on the hike - We found new tactics happening each day: Horsemen and horse fell to the twelve foot pike, 1 We'd stampede cattle into infantry, Retreat through hedges where cavalry must be thrown Until, on Vinegar Hill, the fatal conclave: Twenty thousand died; shaking scythes at cannon. The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave. They buried us without shroud or coffin And in August barley grew up out of the grave. ---- - Seamus Heaney our prouvt repubLLctt"" trttvtLtLo"" Bodenstown is a very special place for Irish republicans. We gather here every year to honour Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen and to rededicate ourselves to the principles they espoused. We remember that it was the actions of the 1916 leaders and their comrades, inspired by such patriot revolutionaries as Tone and Emmett, that lit the flame that eventually destroyed the British Empire and reawakened the republicanism of the Irish people. The first article of the constitution of the Society of United Irishmen stated as its purpose, the 'forwarding a brotherhood of affection, a communion of rights, and an union of power among Irishmen of every religious persuasion'. James Connolly said of Wolfe Tone that he united "the hopes of the new revolutionary faith and the ancient aspirations of an oppressed people". -

Directory of Local Parenting Programmes

Email: [email protected] Phone: 053 9259821 Email: [email protected] Phone: 053 9421374 Dear Service Provider “Progressing Disability Services for Children and Young People is a National directive whose aim is to provide one clear pathway to services for all children and young people with a disability, focusing on the needs of the child/young person and their family”. As part of this directive the HSE formed a Local Implementation Group comprising of HSE personnel involved in the delivery of Paediatric Services. Parent, Department of Education and Section 39 Voluntary agency representatives will also become involved in this process as we move forward. While reviewing current service provision it became apparent that there was a lack of awareness of all the support services that are available for children and their parents in the Wexford area. In order to address this deficit we have put together the attached directory of local supports both Voluntary and HSE run in County Wexford. This directory includes: Parenting Programmes Advocacy Groups Mother and Toddler Groups National Disability Organisations This list while comprehensive is not an exhaustive therefore we would appreciate it if you could inform us of any new developments or groups which may not have been included. We would be grateful if you could distribute this directory to any group or parent whom you feel would benefit from the information. Yours Faithfully Lucy O’Hagan and Louise Smyth Local Leads Progressing Disability Services for Children and Young People Directory of Wexford Parenting Programmes – October 2013 1 Directory of Parent Supports in Wexford Developed by: Louise Smyth L.O/EIT Lucy O’Hagan Senior SLT Disclaimer Information, contact names, telephone numbers, addresses and web links provided in this Directory are for your convenience only and should not be considered as official, endorsed or recommended. -

County Limerick Lineage

Part C: County Limerick Lineage. Contents: 1. Wakefield on Limerick 2. Places of Anglim Residence in the Samuel Lewis' TOPOGRAPHICAL DICTIONARY OF IRELAND (London: S. Lewis, 1846). 3. Parish Map, Barony, and Poor Law Maps of Limerick 4. Anglim Family Lineages. Histories of County Limerick HISTORY OF LIMERICK – 1824 LIMERICK Is an extensive, populous city, and seaport, situated on the Eastern bank of the river Shannon, distant 94 miles south west from Dublin, 50 miles from Cork, 36 from Waterford and 50 from Tralee. It is traditionally supposed to have been built by Yuorus in the year 155, and was anciently much frequented by foreign merchants; and after the arrival of the Danes, in the year 855, these enterprising people considerably improved its commerce. The English took possession of Limerick in the year 1174, and, as a proof of the early importance of the city, in the year 1197, and in the ninth year of the reign of King Richard, he granted a charter to the citizens to elect a mayor, which honor was not obtained by the citizens of London till ten years after that period; nor had Dublin and Cork a mayor till the 13th century. This city was originally walled, and, deemed the strongest fortress in this kingdom, besides having the advantage of not being commanded by adjacent heights, and it has sustained some memorable sieges. In the year 1690 King William brought his forces against it, but withdrew them without accomplishing its reduction; in the following year it was again invested by General Ginckle, who, after an obstinate resistance, compelled the garrison to surrender, on honourable terms of capitulation. -

Council Minutes 2010

County Council Meeting 18.01.10 WEXFORD COUNTY COUNCIL Minutes of Meeting of Wexford County Council Held on Monday, 18 th January, 2010 – 2.30 p.m. In the Council Chamber, County Hall, Wexford. Attendance: In the Chair: Cllr. J. Moore Councillors: M. Byrne; P. Codd; K. Codd-Nolan; P. Cody; K. Doyle; J. Hegarty; T. Howlin; R. Ireton; P. Kavanagh; D. Kennedy; M. Kinsella; G. Lawlor; D. MacPartlin; M. Murphy; L. O’Brien; P. Reck; M. Sheehan; O. Walsh; Officials: Messrs: A. Doyle, D/County Manager, T. Larkin, E. Hore, N. McGuigan, Directors of Services; Ger Mulvey, Head of Finance; E. Taaffe, A/Senior Engineer; B. Galvin, Senior Engineer, G. Forde, Senior Executive Engineer; G. Willis, Civil Defence Officer; G. Griffin County Secretary. Apologies: Councillor T. Dempsey; Councillor. A. Fenlon; Expression of Sympathy : The Council extended sympathy to the following recently bereaved: • Cllr. Tony Dempsey on the death of his son Muiris • Cllr. Larry O’Brien on the death of his mother Stella • Cllr. Ted Howlin on the death of his aunt Annie Howlin • Siobhan Kelly, CO, New Ross, on the death of her mother Marie Roche • Richie Gaynor (Outdoor Staff) on the death of his mother Sadie Gaynor (mother-in-law of Monica Gaynor, Planning Dept) • Hugh O’Connor, Curralcoe on the death of his wife Breda O’Connor The Council observed a minute’s silence. Confirmation of Minutes: On the proposal of Councillor P. Codd, seconded by Councillor T. Howlin, the Council approved the minutes of the County Council Meeting held on 14 th December. On the proposal of Councillor M. -

17989898 Rebellionrebellion Inin Irelandireland

Originally from Red & Black Revolution - see http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/rbr.html TheThe 171717989898 rebellionrebellion inin IrelandIreland In June of 1795 several Irish Protestants gathered on top of Cave Hill, overlooking This article by Andrew Flood was first Belfast. They swore " never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the published (1998) in Red & Black authority of England over our country and asserted our independence". Three Revolution. It is based on a years later 100,000 rose against Britain in the first Irish republican insurrection. much longer draft which Andrew Flood examines what they were fighting for and how they influenced includes discussion of the modern Irish nationalism. radical politics of the period and the pre-rebellion In 1798 Ireland was shook by a mass rebellion for democratic rights and organisation of the United against British rule. 200 years later 1798 continues to loom over Irish Irishmen. This can be read politics. The bi-centenary, co-inciding with the ‘Peace process’, has at- on the internet at tracted considerable discussion, with the formation of local history groups, http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/andrew/1798.html the holding of conferences and a high level of interest in the TV documen- taries and books published around the event. on land and sea, their hairbreadth es- It is rightly said that history is written by trated by the treatment of two portraits of capes and heroic martyrdom, but have the victors. The British and loyalist histo- prominent figures in the rebellion. Lord resolutely suppressed or distorted their rians who wrote the initial histories of the Edward Fitzgerald had his red cravat2 writings, songs and manifestos.”3 rising portrayed it as little more than the painted out and replaced with a white one. -

Murphy Family Papers P141

MURPHY FAMILY PAPERS P141 UCD Archives School of History and Archives archives @ucd.ie www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2004 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS AND STRUCTURE Introduction v Family tree vii SECTION 1: THE PAPERS OF CONN AND ANNIE MURPHY A CORRESPONDENCE OF CORNELIUS J. MURPHY (‘CONN’) AND HIS WIFE, ANNIE, née BYRNE I Letters from Conn to Annie (1892–1936) 1 II Letters from Annie to a. Conn (1892–1926) 21 b. Brigid Burke, her aunt (1915–1928) 21 c. Annie Mary Constance Murphy (‘Connie’), her 26 daughter [c. 1930] III Other letters to both a. from Reverend William S. Donegan (1895–1936) 27 b. from Annie’s friends and acquaintances (1922– 27 1936) c. concerning Annie’s illness and death (1937) 28 B LOVE POETRY OF CONN MURPHY [c.1892–1895] 30 C DEATH OF CORNELIUS MURPHY (Sr) (1917) 31 D PHOTOGRAPHS [c.1880–c.1935] 32 E EPHEMERA I concerning courtship and marriage of Conn and Annie 34 Murphy [c.1892–1895] II Calling cards [c.1925–c.1935] 35 III Passports (1923: 1928) 35 IV Invitation to 31st Eucharistic Congress (1931) 35 V Condolence cards on occasion of Conn Murphy’s death 36 (1947) iii SECTION 2: THE PAPERS OF ANNIE MARY CONSTANCE (‘CONNIE’) MURPHY A CORRESPONDENCE I while teaching/studying at St. Pölten, Austria (1913–1914) 37 II concerning her political activities and imprisonment 47 (c. 1921–1923) III with her parents (1928–1945) 55 B DESMOND BRACKEN MURPHY, her husband I Letters to Connie (c. -

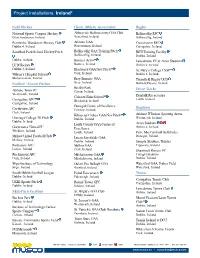

Project Installations: Ireland*

Project Installations: Ireland* Field Hockey Gaelic Athletic Association Rugby National Sports Campus Hockey Abbeyside Ballinacourty GAA Club Ballincollig RFC Blanchardstown, Ireland Waterford, Ireland Ballincollig, Ireland Pembroke Wanderers Hockey Club Athlone GAA Crosshaven RFC Dublin 4, Ireland Roscommon, Ireland Carrigaline, Ireland Sandford Park School Hockey Pitch Ballincollig GAA Training Pitch IRFU Training Facility Ballincollig, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Banteer Astro** Lansdowne FC at Aviva Stadium UCD Hockey Banteer, Ireland Dublin 4, Ireland Dublin 4, Ireland Blackrock GAA New Pitch** St. Mary’s College CSSP** Wilson’s Hospital School Cork, Ireland Dublin 6, Ireland Multyfarnham, Ireland Bray Emmets GAA Thornfield Rugby UCD Bray, Ireland Belfield Downs, Ireland Football / Soccer Pitches Breffni Park Horse Tracks Athlone Town FC Cavan, Ireland Westmeath, Ireland Colaiste Eoin School** Dundalk Racecourse Carrigaline AFC** Blackrock, Ireland Louth, Ireland Carrigaline, Ireland Donegal Centre of Excellence Stadiums Castleview AFC Convoy, Ireland Cork, Ireland Kilmacud Crokes GAA New Pitch** Athl one IT Indoor Sporting Arena Gonzaga College 3G Pitch Dublin, Ireland Westmeath, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Louth County GAA Centre of Aviva Stadium Greystones United FC Excellence Dublin 4, Ireland Wicklow, Ireland Louth, Ireland Pairc MacCumhaill Ballybofey Mallow United Football Club Lucan Sarsfields GAA Donegal, Ireland Mallow, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Semple Stadium, Thurles Portlaoise AFC Mallow GAA Tipperary, Ireland Laoise, Ireland Cork, Ireland Shamrock Rovers FC Rockmount AFC Mitchelstown GAA Tallaght Stadium Cork, Ireland Mitchelstown, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Sligo Institute of Technology Oulart The Ballagh GAA Waterford GAA, Fraher Field Sligo, Ireland Wexford, Ireland Waterford, Ireland South Dublin Football League Pobal Eascarrach Tennis Dublin, Ireland Falcarragh, Ireland Carrigaline Tennis Club UKBL Sports Pitch Round Tower GFC Carrigaline, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Kildare, Ireland Lansdowne Tennis Club Multi-Pitch Facilities St. -

Planning Applications 2016

Planning Applications 2016 Planning No Applicant Location Application Date Decision Date Stage Decision 20160001 THOMAS MURPHY STRANDFIELD, WEXFORD RURAL 04/01/2016 26/02/2016 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS PERMISSION FOR RETENTION AND COMPLETION OF AN ESB SUBSTATION 20160002 MARTIN BUSHER WHITEROCK SOUTH, WEXFORD RURAL 05/01/2016 26/02/2016 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS PERMISSION TO ERECT AN EXTENSION TO SIDE, A SHED TO THE REAR AND TO MAKE MINOR ALTERATIONS TO THE ELEVATIONS TO FACILITATE INTERNAL ALTERATIONS AT 23 WHITEROCK HEIGHTS, WHITEROCK SOUTH, WEXFORD 20160003 NUTRICIA INFANT NUTRITION MAUDLINTOWN, WEXFORD RURAL 05/01/2016 24/02/2016 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS LIMITED PERMISSION FOR AN EXTENSION TO THE EXISTING PRODUCTION BUILDING WHICH WILL CONSIST OF AN EXTENSION TO THE EXISTING OIL STORAGE AREA AND A PROPOSED WASTE HANDLING AREA EXTENSION AT GROUND FLOOR LEVEL AND A PROPOSED NEW CANOPY 20160004 CHRIS HAYES BALLYNAGLOGH, FORTH 06/01/2016 26/02/2016 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS PERMISSION FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF AN ENTRANCE AND ACCESS WAY 20160005 TEAGASC ENVIRONMENT REDMONDSTOWN, RATHASPICK 06/01/2016 06/01/2016 Invalid Application INVALIDATED APPLICATION RESEARCH CENTRE PERMISSION FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF TWO FULLY SERVICED AGRICULTURAL LIVESTOCK BUILDING WITH UNDERGROUND SLURRY STORAGE TANKS, FEED STORE UNIT, AN EXTENSION TO AN EXISTING AGRICULTURAL BUILDING INCORPORATING A LOADING RAMP/OFFICE/STORE/ISOLATION UNIT, CONCRETE APRONS AND ASSOCIATED WORKS WHICH WILL REQUIRE THE REMOVAL OF AN AGRICULTURAL LIVESTOCK BUILDING AND SURFACE SLURRY STORAGE TANK 20160006 ELAINE KENNY KYLE, BOLABOY 08/01/2016 02/03/2016 Decision made GRANTED subject to CONDITIONS PERMISSION TO ERECT A SERVICED DWELLING HOUSE AND A DOMESTIC GARAGE/STORE AND CARRY OUT ALL ASSOCIATED SITE WORKS 20160007 STUART RYAN COLESTOWN, CARRICK 08/01/2016 08/01/2016 Invalid Application INVALIDATED APPLICATION PERMISSION FOR THE MATERIAL CHANGE OF USE OF EXISTING GRANNY FLAT TO A SEPARATE DWELLING. -

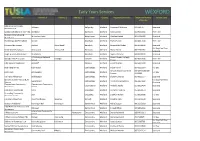

WEXFORD Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type of Service

Early Years Services WEXFORD Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type of Service Ballymitty Community Hilltown Ballymitty Wexford Veronica O'Mahony 051 561767 Sessional Playgroup Clg Rainbow Childcare at Tara Villa Barntown Barntown Wexford Kate Lowney 053 9120066 Part Time Mulrankin Pre School & Mulrankin Castle Bridgetown Wexford Martina Cardiff 087 1334680 Sessional Montessori Paistí Beaga Ltd Pre-school Grange Broadway Wexford Mary O'Leary 087 2437103 Part Time Coisceim Montessori Ardeen Wood Road Bunclody Wexford Bernadette Mahon 087 6509636 Sessional Full Day Part Time Kinderland Montessori Na Crosaire Killmyshall Bunclody Wexford Maria Dunne 087 2763759 Sessional Laugh & Learn Montessori Drumderry Bunclody Wexford Daphne Deacon 085 8388570 Sessional C/O Clologue National Marian Power Kayleigh Clologue Play And Learn Clologue Camolin Wexford 087 6107601 Part Time School Power Little Acorns Montessori Ballyduff Camolin Wexford Jennifer Doyle 087 6330721 Sessional Bright Beginnings Elderwood Castlebridge Wexford Aidan Farrell 087 2260314 Full Day Orlaith Shortle Catherine 087 6745028/089 Castle Kids Ballyboggan Castlebridge Wexford Full Day Boggan 4816866 Tot’ng Up Playschool Ballyboggan Castlebridge Wexford Sharon Edwards 087 9122277 Sessional Wonderwise Pre-School & All Full Day Part Time Sinnottsmill Castlebridge Wexford AnneMarie Steadman 085 285 9247 Daycare Sessional Cleariestown Community Cleariestown Community Cleariestown Wexford Michelle Roche 053 9139424 Sessional -

Kilmuckridge a Project by Michael Fortune

About This Place – Kilmuckridge A Project by Michael Fortune Below are the notes from the Google Map produced by Michael Fortune between June and November 2015. The Google Map features over 130 sites from around the village. This is a living resource and this is a living document. Please contact Michael if you have any more sites to add, or information to change. Let the conversation begin. Michael by phone on 087 6470247 or by email [email protected] ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Proposed Airfield Ned Kavanagh told me that this long, flat stretch of land was earmarked as an airfield for Major Brian who owned Upton House. One of his family members flew and this would have been a direct way to bring clients to Upton House in its day. Any further information on this appreciated. 52.52959, -6.22099 © Information by Michael Fortune, 2015. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Raheen - Ballywater A fine example of a raheen (ringfort). It has been cleared somewhat but the outline is still clear. In the mid- 19th century a farm once stood very close by. The small fields were let into one big field towards the latter part of the 20th century. It's quite a big raheen in comparison to the other ones close by. 52.53607, -6.24765 © Information by Michael Fortune, 2015. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Raheen - Ballinoulart A fine example of a raheen (ringfort). This raheen is interesting as in the old OSI maps we see it had a square perimeter around a rough circle. It is generally accepted that Norman enclosures, of which there are many in the area, were square/rectangle in shape, while the Irish ones were circular. -

A Comparative Study of the Lives of Church of Ireland and Roman Catholic Clergy in the South-Eastern Dioceses of Ireland from 1550 to 1650

A comparative study of the lives of Church of Ireland and Roman Catholic clergy in the south-eastern dioceses of Ireland from 1550 to 1650 by ÁINE HENSEY, BA Thesis for the degree of PhD Department of History National University of Ireland Maynooth Supervisor of Research: Professor Colm Lennon Head of Department: Professor Marian Lyons May 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements ii Abbreviations iv Introduction 1 Chapter One: ‘Tender youths:’ the role of education in the formation and 15 development of the clergy Chapter Two: 60 Material Resources: the critical importance of property and other sources of income in the empowerment of the clergy Chapter Three: 138 The clergy in the community Chapter Four: 211 Church of Ireland institutional support and organisation Chapter Five: 253 Roman Catholic institutional support and organisation Conclusion 318 Appendix 1: 334 A database of Roman Catholic priests believed to be working in the south-eastern dioceses between 1557 and 1650 Bibliography 386 i Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the support and co-operation of staff in the following research facilities: the Manuscripts Room and Early Printed Books Department of Trinity College, Dublin; the Royal Irish Academy; the Representative Church Body Library; Lambeth Palace Library, London; the county libraries in Carlow, Kilkenny and Wexford; the significant online resources of Waterford County Library; and the Russell and John Paul II libraries in NUI Maynooth. I would like to add a special word of thanks to an tAth Séamus de Bhál, archivist at St Peter’s College, Wexford, to Fr David Kelly, archivist of the Irish Augustinians, and to Dr Jason McHugh for generously sharing his research on the Catholic clergy of the Dublin archdiocese in the seventeenth century. -

OULART-THE BALLAGH V FAYTHE HARRIERS

Senior hurling final 2012 pages_Layout 1 29/11/2012 15:17 Page 1 Cluichí Ceannais Iomáint Loch Garman 2012 Pettitt’s Senior Hurling Championship Final OULART-THE BALLAGH v FAYTHE HARRIERS Club Wexford-Creane & Creane Minor Hurling Championship Final RAPPAREES v NAOMH ÉANNA Clár Oifigiúl Rúnaí Luach €3 Senior hurling final 2012 pages_Layout 1 29/11/2012 15:17 Page 2 Senior hurling final 2012 pages_Layout 1 29/11/2012 15:17 Page 3 Senior hurling final 2012 pages_Layout 1 29/11/2012 15:17 Page 4 PROUD SPONSORS OF WEXFORD “WE KNOW SPORT” STORES LOCATED IN: WEXFORD NEW ROSS GOREY ENNISCORTHY DUNGARVAN Senior hurling final 2012 pages_Layout 1 29/11/2012 15:17 Page 5 Senior hurling final 2012 pages_Layout 1 29/11/2012 15:17 Page 6 Senior hurling final 2012 pages_Layout 1 29/11/2012 15:18 Page 7 crprint.ie 053 92 35295 Senior hurling final 2012 pages_Layout 1 29/11/2012 15:18 Page 8 Wexford Park, October 14 , 2 012 Rival Senior Hurling captains, Jim Berry, Faythe Harriers (left) and Keith Rossiter (Oulart-the Ballagh) (right) being congratulated on reaching the Pettitt's Senior Hurling Final 2012 by Cormac Pettitt, main sponsor of the Wexfo rd Sen ior H urling Ch ampio nship. Chief programme seller Gay Stafford always goes about his job with a smile on his face. His welcom e to everyon e who come s to We xford Park is gen uine and much appreciated by all. Thank you for all your work during the year Gay. 17 Senior hurling final 2012 pages_Layout 1 29/11/2012 15:18 Page 9 Oulart-The Ballagh G.A.A acknowledges and appreciates the practical support, co-operation and financial help of a great number of people and businesses and takes this opportunity to express its sincere gratitude to everyone who supported or assisted the club, in any way, throughout the year.