The Memoirs of James H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1798) the Pockets of Our Great-Coats Full of Barley (No Kitchens on the Run, No Striking Camp) We Moved Quick and Sudden in Our Own Country

R..6~t6M FOR.. nt6 tR..tSH- R..6lS6LS (Wexford, 1798) The pockets of our great-coats full of barley (No kitchens on the run, no striking camp) We moved quick and sudden in our own country. The priest lay behind ditches with the tramp. A people, hardly marching - on the hike - We found new tactics happening each day: Horsemen and horse fell to the twelve foot pike, 1 We'd stampede cattle into infantry, Retreat through hedges where cavalry must be thrown Until, on Vinegar Hill, the fatal conclave: Twenty thousand died; shaking scythes at cannon. The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave. They buried us without shroud or coffin And in August barley grew up out of the grave. ---- - Seamus Heaney our prouvt repubLLctt"" trttvtLtLo"" Bodenstown is a very special place for Irish republicans. We gather here every year to honour Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen and to rededicate ourselves to the principles they espoused. We remember that it was the actions of the 1916 leaders and their comrades, inspired by such patriot revolutionaries as Tone and Emmett, that lit the flame that eventually destroyed the British Empire and reawakened the republicanism of the Irish people. The first article of the constitution of the Society of United Irishmen stated as its purpose, the 'forwarding a brotherhood of affection, a communion of rights, and an union of power among Irishmen of every religious persuasion'. James Connolly said of Wolfe Tone that he united "the hopes of the new revolutionary faith and the ancient aspirations of an oppressed people". -

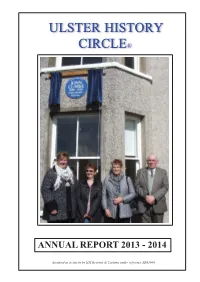

Annual Report 2013-2014

® $118$/5(3257 $FFHSWHGDVDFKDULW\E\+05HYHQXH &XVWRPVXQGHUUHIHUHQFH;5 ULSTER HISTORY CIRCLE ® ANNUAL REPORT 2013 - 2014 8/67(5+,6725<&,5&/( $118$/ 5(3257 Cover photograph: John Clarke plaque unveiling, 25 April 2013 Copyright © Ulster History Circle 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means; electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher. Published by the Ulster History Circle ULSTER HISTORY CIRCLE ® ANNUAL REPORT 2012 - 2013 :LOOLH-RKQ.HOO\EURWKHURI7KRPDV5D\PRQG.HOO\*&DQGPHPEHUVRIWKHZLGHU.HOO\IDPLO\ZLWK 5D\PRQG¶V*HRUJH&URVVDQG/OR\GV¶*DOODQWU\0HGDOVDIWHUXQYHLOLQJWKHSODTXHRQ'HFHPEHULQ 1HZU\ ULSTER HISTORY CIRCLE ® ANNUAL REPORT 2013 - 2014 Foreword The past year has seen a total of seventeen plaques erected by the Ulster History Circle, a significant increase on the nine of the previous year. These latest plaques are spread across Ulster, from Newry in the south east, to the north west in Co Donegal. Apart from our busy plaque activities, the Circle has been hard at work enhancing the New Dictionary of Ulster Biography. All our work is unpaid, and Circle members meet regularly in committee every month, as fundraising and planning the plaques are always on-going activities, with the summer months often busy with events. I would like to thank my colleagues on the Circle committee for their support and their valued contributions throughout the year. A voluntary body like ours depends entirely on the continuing commitment of its committee members. On behalf of the Circle I would also like to record how much we appreciate the generosity of our funders: many of the City and District Councils, and those individuals, organisations, and businesses without whose help and support the Circle could not continue in its work commemorating and celebrating the many distinguished people from, or significantly connected with, Ulster, who are exemplified by those remembered this year. -

Contents PROOF

PROOF Contents Notes on the Contributors vii Introduction 1 1 The Men of Property: Politics and the Languages of Class in the 1790s 7 Jim Smyth 2 William Thompson, Class and His Irish Context, 1775–1833 21 Fintan Lane 3 The Rise of the Catholic Middle Class: O’Connellites in County Longford, 1820–50 48 Fergus O’Ferrall 4 ‘Carrying the War into the Walks of Commerce’: Exclusive Dealing and the Southern Protestant Middle Class during the Catholic Emancipation Campaign 65 Jacqueline Hill 5 The Decline of Duelling and the Emergence of the Middle Class in Ireland 89 James Kelly 6 ‘You’d be disgraced!’ Middle-Class Women and Respectability in Post-Famine Ireland 107 Maura Cronin 7 Middle-Class Attitudes to Poverty and Welfare in Post-Famine Ireland 130 Virginia Crossman 8 The Industrial Elite in Ireland from the Industrial Revolution to the First World War 148 Andy Bielenberg v October 9, 2009 17:15 MAC/PSMC Page-v 9780230_008267_01_prex PROOF vi Contents 9 ‘Another Class’? Women’s Higher Education in Ireland, 1870–1909 176 Senia Pašeta 10 Class, Nation, Gender and Self: Katharine Tynan and the Construction of Political Identities, 1880–1930 194 Aurelia L. S. Annat 11 Leadership, the Middle Classes and Ulster Unionism since the Late-Nineteenth Century 212 N. C. Fleming 12 William Martin Murphy, the Irish Independent and Middle-Class Politics, 1905–19 230 Patrick Maume 13 Planning and Philanthropy: Travellers and Class Boundaries in Urban Ireland, 1930–75 249 Aoife Bhreatnach 14 ‘The Stupid Propaganda of the Calamity Mongers’?: The Middle Class and Irish Politics, 1945–97 271 Diarmaid Ferriter Index 289 October 9, 2009 17:15 MAC/PSMC Page-vi 9780230_008267_01_prex PROOF 1 The Men of Property: Politics and the Languages of Class in the 1790s Jim Smyth Political rhetoric in Ireland in the 1790s – the sharply conflicting vocabularies of reform and disaffection, liberty, innovation. -

17989898 Rebellionrebellion Inin Irelandireland

Originally from Red & Black Revolution - see http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/rbr.html TheThe 171717989898 rebellionrebellion inin IrelandIreland In June of 1795 several Irish Protestants gathered on top of Cave Hill, overlooking This article by Andrew Flood was first Belfast. They swore " never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the published (1998) in Red & Black authority of England over our country and asserted our independence". Three Revolution. It is based on a years later 100,000 rose against Britain in the first Irish republican insurrection. much longer draft which Andrew Flood examines what they were fighting for and how they influenced includes discussion of the modern Irish nationalism. radical politics of the period and the pre-rebellion In 1798 Ireland was shook by a mass rebellion for democratic rights and organisation of the United against British rule. 200 years later 1798 continues to loom over Irish Irishmen. This can be read politics. The bi-centenary, co-inciding with the ‘Peace process’, has at- on the internet at tracted considerable discussion, with the formation of local history groups, http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/andrew/1798.html the holding of conferences and a high level of interest in the TV documen- taries and books published around the event. on land and sea, their hairbreadth es- It is rightly said that history is written by trated by the treatment of two portraits of capes and heroic martyrdom, but have the victors. The British and loyalist histo- prominent figures in the rebellion. Lord resolutely suppressed or distorted their rians who wrote the initial histories of the Edward Fitzgerald had his red cravat2 writings, songs and manifestos.”3 rising portrayed it as little more than the painted out and replaced with a white one. -

Irish Political Portraits

13 28 [COLLINS & GRIFFITH] A rare poster of Arthur Griffith, Michael Collins, Sean MacEoin (The Blacksmith of Ballinalee), Richard Mulcahy and President De Valera. The medallion portraits within a Celtic decorated border and the landscape portrait of De Valera is against a draped tricolour and sunburst. Framed. 30.5 x 30.5cm. In August 1921, de Valera secured Dáil Éireann approval to change the 1919 Dáil Con- stitution to upgrade his office from prime minister or chairman of the cabinet to a full President of the Republic. Declaring himself now the Irish equivalent of King George V, he argued that as Irish head of state, in the absence of the British head of state from the negotiations, he too should not attend the Treaty Negotiations at which British and Irish government leaders agreed to the effective independence of twenty-six of Ireland’s thirty-two counties as the Irish Free State, with Northern Ireland choosing to remain under British sovereignty. It is generally agreed by historians that whatever his motives, it was a mistake for de Valera not to have travelled to London. Lot 31 A rare and interesting item. Lot 29 €250 - 350 29 [IRISH BRIGADE] Victorious Charge of the Irish Brigade 11th May, 1745. 30 [IRISH PATRIOTS] The United Irish Patriots 1798. French Commander: Marshall Morris - English Commander: Duke of Cumberland. A coloured lithograph showing the ‘patriots of 1798’ seated and standing with in a col- Coloured lithograph. Framed. 70.0 x 35.0cm. Chicago: Kurz & Allison Art Publishers. onnaded assembly room. Framed. 66 x 52cm. Some surface scratches. -

Murphy Family Papers P141

MURPHY FAMILY PAPERS P141 UCD Archives School of History and Archives archives @ucd.ie www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2004 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS AND STRUCTURE Introduction v Family tree vii SECTION 1: THE PAPERS OF CONN AND ANNIE MURPHY A CORRESPONDENCE OF CORNELIUS J. MURPHY (‘CONN’) AND HIS WIFE, ANNIE, née BYRNE I Letters from Conn to Annie (1892–1936) 1 II Letters from Annie to a. Conn (1892–1926) 21 b. Brigid Burke, her aunt (1915–1928) 21 c. Annie Mary Constance Murphy (‘Connie’), her 26 daughter [c. 1930] III Other letters to both a. from Reverend William S. Donegan (1895–1936) 27 b. from Annie’s friends and acquaintances (1922– 27 1936) c. concerning Annie’s illness and death (1937) 28 B LOVE POETRY OF CONN MURPHY [c.1892–1895] 30 C DEATH OF CORNELIUS MURPHY (Sr) (1917) 31 D PHOTOGRAPHS [c.1880–c.1935] 32 E EPHEMERA I concerning courtship and marriage of Conn and Annie 34 Murphy [c.1892–1895] II Calling cards [c.1925–c.1935] 35 III Passports (1923: 1928) 35 IV Invitation to 31st Eucharistic Congress (1931) 35 V Condolence cards on occasion of Conn Murphy’s death 36 (1947) iii SECTION 2: THE PAPERS OF ANNIE MARY CONSTANCE (‘CONNIE’) MURPHY A CORRESPONDENCE I while teaching/studying at St. Pölten, Austria (1913–1914) 37 II concerning her political activities and imprisonment 47 (c. 1921–1923) III with her parents (1928–1945) 55 B DESMOND BRACKEN MURPHY, her husband I Letters to Connie (c. -

Kilmuckridge a Project by Michael Fortune

About This Place – Kilmuckridge A Project by Michael Fortune Below are the notes from the Google Map produced by Michael Fortune between June and November 2015. The Google Map features over 130 sites from around the village. This is a living resource and this is a living document. Please contact Michael if you have any more sites to add, or information to change. Let the conversation begin. Michael by phone on 087 6470247 or by email [email protected] ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Proposed Airfield Ned Kavanagh told me that this long, flat stretch of land was earmarked as an airfield for Major Brian who owned Upton House. One of his family members flew and this would have been a direct way to bring clients to Upton House in its day. Any further information on this appreciated. 52.52959, -6.22099 © Information by Michael Fortune, 2015. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Raheen - Ballywater A fine example of a raheen (ringfort). It has been cleared somewhat but the outline is still clear. In the mid- 19th century a farm once stood very close by. The small fields were let into one big field towards the latter part of the 20th century. It's quite a big raheen in comparison to the other ones close by. 52.53607, -6.24765 © Information by Michael Fortune, 2015. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Raheen - Ballinoulart A fine example of a raheen (ringfort). This raheen is interesting as in the old OSI maps we see it had a square perimeter around a rough circle. It is generally accepted that Norman enclosures, of which there are many in the area, were square/rectangle in shape, while the Irish ones were circular. -

![Secret Service Under Pitt [Microform]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7516/secret-service-under-pitt-microform-4067516.webp)

Secret Service Under Pitt [Microform]

THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY From the collection of James Collins, Drumcondra, Ireland. Purchased, 1918. 9^/57 Co I inefl. 8*0., priea 143,, __ SfiBViCaviqi UNDER' FITT. By W. J. I mftfATMCK. F.S.A.. Anthorof " Prirate CowMpond-ii I Imd Kemoirs of D«iiel O'ConneU. M.P.. ' &c. ' "The extentive . Satiiidftr Keview."— asd veculiunow- tmg» poSMSsed by Mr. S'it'Patrii:!c has be«n ^e^ibited tir atnMBts in divera boDks-befora 'Secret Service Under rPitt.' But we do not kaowthat in any of these it has shown ' VattUt to freat^r advantage than in the present olume. people will experience no difficulty and find much pl( _ ._ inlMMaidinx. r . A better addition to the curlosititti of ' histoid we have not lately seen.'] A. ' SMCRBT SERVICE UNDER PITT. v. S'_ ^ ' Times."—" Mr. Fit/Patrick cleaie up sonie louK-stand* tecmyaterieiwitii ereat sscacitr. and by meanyofhis minute Mtaprttfoofld Knowledge 01 documents, persons. ancfpTents, ~f(aoceeds in iUuminatinar some of the darkest pasaases ia the, | SwrtniT of I^>fi{''f0u3Blracy, and of the treachery ao con- ftkauy akaoMKed with it. On almost every pace he ttdrowa aaAdtnentic and instructive lisbt on the darker sidea €rf the Irishhigtoity of the times jvith- which h>i is dealing. 4^'. 'Jncvturatrick's book may be commended alike for a» jlktoncal lapbrtaace and for its intriaeic intereat." Xijoad^n : lAngmana. Gieen. and Oo. The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. -

Orr, Jennifer (2011) Fostering an Irish Writers' Circle: a Revisionist Reading of the Life and Works of Samuel Thomson, an Ulster Poet (1766- 1816)

Orr, Jennifer (2011) Fostering an Irish writers' circle: a revisionist reading of the life and works of Samuel Thomson, an Ulster poet (1766- 1816). PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2664/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Fostering an Irish Writers’ Circle: a Revisionist Reading of the Life and Works of Samuel Thomson, an Ulster Poet (1766-1816) A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Scottish Literature at the University of Glasgow, December 2010 by Jennifer Orr © Jennifer Orr December 2010 Contents Acknowledgements i. Abstract ii. Abbreviations iii. Introduction 1-7 Chapter 1 The Patrons and the Pundits 8-40 Chapter 2 Revising Robert Burns for Ireland: Thomson and the Scottish Tradition 41-79 Chapter 3 ‘For you, wi’ all the pikes ye claim’: Patriotism, Politics and the Press 80-125 Chapter 4 ‘Here no treason lurks’ – Rehabilitating the Bard in the Wake of Union 1798-1801 126-174 Chapter 5 ‘‘Lowrie Nettle’ – Thomson and Satire 1799-1806 175-211 Chapter 6 Simple Poems? Radical Presbyterianism and Thomson’s final edition 1800-1816 212-251 Chapter 7 The Fraternal Knot – Fostering an Irish Romantic Circle 252-293 Conclusion 294-301 Bibliography 302-315 i Acknowledgements First and foremost, my sincere thanks to Dr. -

Dublin Founders of Ringing Bells

The Weekly Journal for No. 4754 June 7, 2002 Price £1.45 Church Bell Ringers since 1911 Editor: Robert lewis Dublin Founders of Ringing Bells The refurbishment and rehanging in a new frame in 1989 of the eight bells of St Patrick's Cathedral in Melbourne, Australia, was an indirect compliment to the quality of Irish workmanship. The bells, with a tenor of 13'/z cwt, were cast in Dublin by Murphy's Bell Foundry to the order of Bishop Goold. They arrived in Melbourne in 1853. The bells were intended for St Francis' Church in Elizabeth Street, Melbourne, which had no tower! Eventually, in 1868, they were hung in the south tower of the cathedral. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries there were at least four founders in Dublin who cast ringing bells: John Murphy, James Sheridan, Thomas Hodges and Matthew O'Byrne. John Murphy John Murphy was a Coppersmith who established his business at 109 James's Street, Dublin, in 1837. In 1843 he branched-out into bell founding, casting a bell for the Roman Catholic church in Tuam in Co Galway. In the years that followed Murphy cast many single bells and at least eight rings of bells. In 1877 Murphy cast the Tenor for Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin and it is a matter of some regret that this bell was sent to Taylor's Bell Foundry in 1979 and recast. The writer called a quarter peal of Grandsire Triples on the back eight in 1967 and, apart from the go of the bells, enjoyed their music. -

The Contested Geographies of Irish Democratic Political Cultures in the 1790S

‘We will have equality and liberty in Ireland’: The Contested Geographies of Irish Democratic Political Cultures in the 1790s David Featherstone School of Geographical and Earth Sciences University of Glasgow ABSTRACT: This paper explores the contested geographies of Irish democratic political cultures in the 1790s. It positions Irish democratic political cultures in relation to Atlantic flows and circulations of radical ideas and political experience. It argues that this can foreground forms of subaltern agency and identity that have frequently been marginalized in different traditions of Irish historiography. The paper develops these arguments through a discussion of the relations of the United Irishmen to debates on slavery and anti-slavery. Through exploring the influence of the ex- slave and abolitionist Olaudah Equiano on these debates it foregrounds the relations between the United Irishmen and the Black Atlantic. The paper examines the limits of some of the United Irishmen’s democratic politics. It argues that the articulations of liberty and equality by Irish sailors in mutinies in the late 1790s dislocated some of the narrow notions of democratic community and politics associated with the United Irishmen. Unheeding the clamour that maddens the skies As ye trample the rights of your dark fellow men When the incense that glows before liberty’s shrine Is unmixed with the blood of the galled and oppressed, Oh then and then only, the boast may be thine That the star spangled banner is stainless and blest.1 hese trenchant lines were written by the Antrim weaver and United Irishman (UI) James Hope in his poem, “Jefferson’s Daughter.” His autobiography noted the impact of the TAmerican Revolution on Ireland, arguing that “the American struggle taught people, that industry had rights as well as aristocracy, that one required a guarantee, as well as the other; which gave extension to the forward view of the Irish leaders.”2 His poem, however, affirms the extent to which his identification with the American Revolution was critical. -

Ancient Order of Hibernians

St Brendan The Navigator Feast Day May 16th Ancient Order of Hibernians St Brendan the Navigator Division Mecklenburg County Division # 2 ISSUE #11 MONTHLY NEWSLETTER VOLUME# 5 November 2013 Our next business meeting is on Tuesday, November 12th at 7:30 PM St Mark’s Parish Center, Room 200/201 2013 Officers Chaplain Father Matthew Codd President Ray FitzGerald Vice President Dick Seymour Secretary Tom Vaccaro Treasurer Chris O’Keefe Fin. Secretary Ron Haley Standing Committee Patrick Phelan Marshall Walt Martin Sentinel Frank Fay Past President Joseph Dougherty www.aohmeck2.org Féadfaidh an Máthair Naofa an dochar de na blianta a ghlacadh ar shiúl ó leat. May the Holy Mother take the harm of the years away from you. President’s Message Brother Hibernians, November is the month where we pray for the souls of the faithful departed. In addition to praying for our deceased family members and friends, let us remember our departed Brother Hibernians, especially the deceased member of our Division, Mike Johns. We ask for continued prayers for Brother Ron Haley as he begins his radiation therapy. I recently spoke with Ron and he is feeling well, all things considered, other than for some tiredness and lingering back pain. We hope he will be up and about and in attendance at our upcoming meetings and events. I wish to thank those Brothers who quickly volunteered to be on call if Ron or Kathleen needed some transportation or other assistance. Also, keep Brother Frank Flynn’s son and daughter-in-law in your prayers as they struggle with their illnesses.