Amy Smith-Stewart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hip Hop Pedagogies of Black Women Rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Guillory, Nichole Ann, "Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 173. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/173 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SCHOOLIN’ WOMEN: HIP HOP PEDAGOGIES OF BLACK WOMEN RAPPERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Nichole Ann Guillory B.S., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.Ed., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 1998 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Nichole Ann Guillory All Rights Reserved ii For my mother Linda Espree and my grandmother Lovenia Espree iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am humbled by the continuous encouragement and support I have received from family, friends, and professors. For their prayers and kindness, I will be forever grateful. I offer my sincere thanks to all who made sure I was well fed—mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I would not have finished this program without my mother’s constant love and steadfast confidence in me. -

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

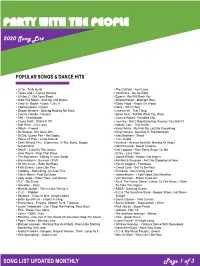

View the Full Song List

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Polish Musicians Merge Art, Business the INAUGURAL EDITION of JAZZ FORUM SHOWCASE POWERED by Szczecin Jazz—Which Ran from Oct

DECEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Two Minute Brother: Contestation Through Gender,`Race' and Sexuality

Title: Two minute brother: Contestation through gender,`race' and sexuality. Authors: Skeggs, Beverley Source: Innovation: The European Journal of Social Sciences; 1993, Vol. 6 Issue 3, p299, 24p Persistent link to this http://0- record: search.epnet.com.library.lib.asu.edu:80/direct.asp?an=9707202871&db=afh Database: Academic Search Elite TWO MINUTE BROTHER: CONTESTATION THROUGH GENDER 'RACE' AND SEXUALITY Is this all you got? Contents one minute and you go pop yous a big disgrace Rap music as I don't mush you all in yer face political dialogue telling me lies like you a real good lover yous a two-minute brother Black I hate guys who talk a lot of shit how they last long and got good dicks masculinities and talking shit and telling me lies . the best lover? Black male they all two-minute brothers sexuality Black girl kick it, Black girl just kick that shit Female rappers (repx6) talk Black, talk BWP in effect once again for all you females across America. back (Bytches with Problems, 1991) Talking back to So much for supporting the male ego, doing the work of emotional civilization management, being unable to express sexuality and being unable to Talking back challenge directly the male performance. This is not the reproduction of against femininity but the music which refuses to be contained by it. These lyrics explore the fraudulent myths of male sexual performance. They Speaking to: come from women who have no economic and/or emotional investment in men. They don't pander to politeness; this is an all-out battle within Conclusion sexual politics. -

Music 6581 Songs, 16.4 Days, 30.64 GB

Music 6581 songs, 16.4 days, 30.64 GB Name Time Album Artist Rockin' Into the Night 4:00 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Caught Up In You 4:37 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Hold on Loosely 4:40 Wild-Eyed Southern Boys .38 Special Voices Carry 4:21 I Love Rock & Roll (Hits Of The 80's Vol. 4) 'Til Tuesday Gossip Folks (Fatboy Slimt Radio Mix) 3:32 T686 (03-28-2003) (Elliott, Missy) Pimp 4:13 Urban 15 (Fifty Cent) Life Goes On 4:32 (w/out) 2 PAC Bye Bye Bye 3:20 No Strings Attached *NSYNC You Tell Me Your Dreams 1:54 Golden American Waltzes The 1,000 Strings Do For Love 4:41 2 PAC Changes 4:31 2 PAC How Do You Want It 4:00 2 PAC Still Ballin 2:51 Urban 14 2 Pac California Love (Long Version 6:29 2 Pac California Love 4:03 Pop, Rock & Rap 1 2 Pac & Dr Dre Pac's Life *PO Clean Edit* 3:38 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2006 2Pac F. T.I. & Ashanti When I'm Gone 4:20 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3:58 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Bailen (Reggaeton) 3:41 Tropical Latin September 2002 3-2 Get Funky No More 3:48 Top 40 v. 24 3LW Feelin' You 3:35 Promo Only Rhythm Radio July 2006 3LW f./Jermaine Dupri El Baile Melao (Fast Cumbia) 3:23 Promo Only - Tropical Latin - December … 4 En 1 Until You Loved Me (Valentin Remix) 3:56 Promo Only: Rhythm Radio - 2005/06 4 Strings Until You Love Me 3:08 Rhythm Radio 2005-01 4 Strings Ain't Too Proud to Beg 2:36 M2 4 Tops Disco Inferno (Clean Version) 3:38 Disco Inferno - Single 50 Cent Window Shopper (PO Clean Edit) 3:11 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2005 50 Cent Window Shopper -

Automatic Recognition of Samples in Musical Audio

Automatic Recognition of Samples in Musical Audio Jan Van Balen MASTER THESIS UPF / 2011 Master in Sound and Music Computing. Supervisors: PhD Joan Serr`a,MSc. Martin Haro Department of Information and Communication Technologies Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona Acknowledgement I wish to thank my supervisors Joan Serr`aand Martin Haro for their priceless guidance, time and expertise. I would also like to thank Perfecto Herrera for his very helpful feedback, my family and classmates for their support and insightful remarks, and the many friends who were there to provide me with an excessive collection of sampled music. Finally I would like to thank Xavier Serra and the Music Technology Group for making all this possible by accepting me to the master. Abstract Sampling can be described as the reuse of a fragment of another artist's recording in a new musical work. This project aims at developing an algorithm that, given a database of candidate recordings, can detect samples of these in a given query. The problem of sample identification as a music information retrieval task has not been addressed before, it is therefore first defined and situated in the broader context of sampling as a musical phenomenon. The most relevant research to date is brought together and critically reviewed in terms of the requirements that a sample recognition system must meet. The assembly of a ground truth database for evaluation was also part of the work and restricted to hip hop songs, the first and most famous genre to be built on samples. Techniques from audio fingerprinting, remix recognition and cover detection, amongst other research, were used to build a number of systems investigating different strategies for sample recognition. -

Moby Play Mp3, Flac, Wma

Moby Play mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Play Country: Russia Style: Breakbeat, Leftfield, Downtempo MP3 version RAR size: 1587 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1293 mb WMA version RAR size: 1135 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 872 Other Formats: MP2 AC3 MP3 AUD MP1 MP4 ASF Tracklist Hide Credits Honey A1 Mixed By – Mario Caldato Jr. A2 Find My Baby Porcelain A3 Vocals – MobyVocals [Additional] – Pilar Basso Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad? A4 Vocals – Shining Light Gospel Choir* South Side B1 Vocals – Moby B2 Rushing Bodyrock B3 Vocals [Additional] – Nikki D.*Written-By [Sample] – Bobby Robinson Natural Blues B4 Mixed By [Mixed In Sheffield By] – I Monster Machete C1 Vocals – Moby C2 7 C3 Run On C4 Down Slow If Things Were Perfect C5 Vocals – MobyVocals [Additional] – Reggie Matthews C6 Everloving D1 Inside D2 Guitar Flute & String The Sky Is Broken D3 Vocals – Moby D4 My Weakness Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Mute Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Mute Records Ltd. Licensed From – Atlantic Recording Corporation Licensed From – Warner Special Products Licensed From – Enjoy Records, Inc. Published By – Little Idiot Music Published By – Warner-Tamerlane Published By – Bobby Robinson Music Distributed By – Vital Mastered At – The Exchange Pressed By – P.R. Records Limited Credits Design [Album Design] – Ysabel Zu Innhausen Und Knyphausen Instruments [All Instruments Played By] – Moby Management [European] – DEF* Management [North American] – MCT Mastered By – GRAZ* Photography By – Corine Day Written-By, Producer, Engineer, Mixed By – Moby Notes Comes with two colour-printed die-cut photo-gimmick inner sleeves (picture is complete with the labels). -

Digital Bootcamp Songwriting Workshop

March 2019 www.torontobluessociety.com Published by the TORONTO BLUES SOCIETY since 1985 [email protected] Vol 35, No 3 PHOTO BY LISA MACINTOSH LISA BY PHOTO Kingston’s Miss Emily is at Hugh’s Room Live March 8, Drom Taberna March 9 [Songwriting Workshop] and just confirmed for the Women’s Blues Revue November 29 CANADIAN PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT #40011871 Digital Bootcamp John’s Blues Picks Songwriting Workshop Loose Blues News Remembering Jackie Shane Event Listings TORONTO BLUES SOCIETY 910 Queen St. W. Ste. B04 Toronto, Canada M6J 1G6 Tel. (416) 538-3885 Toll-free 1-866-871-9457 Email: [email protected] Website: www.torontobluessociety.com MapleBlues is published monthly by the Toronto Blues Society ISSN 0827-0597 2019 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Derek Andrews (President), Janet Alilovic, Jon Arnold, Matt Douris, Lucie Dufault (Vice-President), Carol Flett (Secretary), Sarah French, Lori Murray, Ed Parsons, Paul Sanderson, Mike Smith, Earl Tucker, John Valenteyn (Executive) Musicians Advisory Council: Brian Blain, Gary Kendall, Samantha Martin, Lily Sazz, Mark Stafford, Jenie Thai, Suzie Vinnick,Ken Whiteley Fundraising Committee: Derek Andrews, Jon Arnold, Mike Smith Volunteer & Membership Committee: Lucie Dufault, Sarah French, Rose Ker, Mike Smith, Ed Parsons, Carol Flett Grants Officer: Barbara Isherwood Office Staff: Hüma Üster (Office Manager) Amanda Rheaume (Project Manager) Publisher/Editor-in-Chief: Derek Andrews Managing Editor: Brian Blain [email protected] Contributing Editors: John Valenteyn, Janet Alilovic, Hüma Üster, Carol Flett Listings Coordinator: Janet Alilovic Mailing and Distribution: Ed Parsons Become a member of the Toronto Blues Society, and get connected with Canada's premier blues Advertising: Dougal Bichan events, releases, and our great blues community. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A.