The Nat's Amphibian and Reptile Atlas of Peninsular California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chuckwalla Habitat in Nevada

Final Report 7 March 2003 Submitted to: Division of Wildlife, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State of Nevada STATUS OF DISTRIBUTION, POPULATIONS, AND HABITAT RELATIONSHIPS OF THE COMMON CHUCKWALLA, Sauromalus obesus, IN NEVADA Principal Investigator, Edmund D. Brodie, Jr., Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2485 Co-Principal Investigator, Thomas C. Edwards, Jr., Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5210 (435)797-2509 Research Associate, Paul C. Ustach, Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2450 1 INTRODUCTION As a primary consumer of vegetation in the desert, the common chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus (=ater; Hollingsworth, 1998), is capable of attaining high population density and biomass (Fitch et al., 1982). The 21 November 1991 Federal Register (Vol. 56, No. 225, pages 58804-58835) listed the status of chuckwalla populations in Nevada as a Category 2 candidate for protection. Large size, open habitat and tendency to perch in conspicuous places have rendered chuckwallas particularly vulnerable to commercial and non-commercial collecting (Fitch et al., 1982). Past field and laboratory studies of the common chuckwalla have revealed an animal with a life history shaped by the fluctuating but predictable desert climate (Johnson, 1965; Nagy, 1973; Berry, 1974; Case, 1976; Prieto and Ryan, 1978; Smits, 1985a; Abts, 1987; Tracy, 1999; and Kwiatkowski and Sullivan, 2002a, b). Life history traits such as annual reproductive frequency, adult survivorships, and population density have all varied, particular to the population of chuckwallas studied. Past studies are mostly from populations well within the interior of chuckwalla range in the Sonoran Desert. -

Life History of the Marbled Whiptail Lizard Aspidoscelis Marmorata from the Central Chihuahuan Desert, Mexico

Acta Herpetologica 8(2): 81-91, 2013 Life history of the Marbled Whiptail Lizard Aspidoscelis marmorata from the central Chihuahuan Desert, Mexico Héctor Gadsden1, Gamaliel Castañeda2 1 Instituto de Ecología, A. C.-Centro Regional Chihuahua, Cubículo 29C, Miguel de Cervantes No. 120, Complejo Industrial Chihuahua, C. P. 31109, Chihuahua, Chihuahua, México. Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas. Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango. Avenida Universidad s/n. Fraccionamiento Filadelfia. Gómez Palacio, 35070, Durango, México Submitted on 2012, 5th December; revised on 2013, 10th August; accepted on 2013, 3rd September. Abstract. The life history of a population of marbled whiptail lizard, Aspidoscelis marmorata, was examined from 1989 to 1994 in the sand dunes of the Biosphere Reserve of Mapimí, in Northern México. Lizards were studied using mark- recapture techniques. Reproduction in females occurred between May and August, with birth hatchlings matching the wet season in August. Reproductive activity was highest in the early wet season (July). Males and females reached adult size class at an average age of 1.7 years and 1.8 years, respectively. Body size of males attained an asymptote around 90 mm snout-vent length and females around 82 mm snout-vent length, at an age of approximately 3.6 years and 3.0 years, respectively. The density varied from 7 to 85 individuals / 1.0 ha. The Mexican population had late maturity, relatively long life expectancy, and fewer offspring. Overall, the observed data for A. marmorata and the expectations of life history theory for a late maturing species (K-rate selection) are in agreement. -

Reptile and Amphibian List RUSS 2009 UPDATE

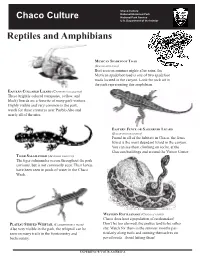

National CHistoricalhaco Culture Park National ParkNational Service Historical Park Chaco Culture U.S. DepartmentNational of Park the Interior Service U.S. Department of the Interior Reptiles and Amphibians MEXICAN SPADEFOOT TOAD (SPEA MULTIPLICATA) Best seen on summer nights after rains, the Mexican spadefoot toad is one of two spadefoot toads located in the canyon. Look for rock art in the park representing this amphibian. EASTERN COLLARED LIZARD (CROTAPHYTUS COLLARIS) These brightly colored (turquoise, yellow, and black) lizards are a favorite of many park visitors. Highly visible and very common in the park, watch for these creatures near Pueblo Alto and nearly all of the sites. EASTERN FENCE OR SAGEBRUSH LIZARD (SCELOPORUS GRACIOSUS) Found in all of the habitats in Chaco, the fence lizard is the most abundant lizard in the canyon. You can see them climbing on rocks, at the Chacoan buildings and around the Visitor Center. TIGER SALAMANDER (ABYSTOMA TIGRINUM) The tiger salamander occurs throughout the park environs, but is not commonly seen. Their larvae have been seen in pools of water in the Chaco Wash. WESTERN RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS VIRIDIS) Chaco does host a population of rattlesnakes! PLATEAU STRIPED WHIPTAIL (CNEMIDOPHORUS VALOR) Don’t be too alarmed, the snakes tend to be rather Also very visible in the park, the whiptail can be shy. Watch for them in the summer months par- seen on many trails in the frontcountry and ticularly along trails and sunning themselves on backcountry. paved roads. Avoid hitting them! EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA Amphibian and Reptile List Chaco Culture National Historical Park is home to a wide variety of amphibians and reptiles. -

Roadrunner Fact Sheet

Roadrunner Fact Sheet Common Name: Roadrunner Scientific Name: Geococcyx Californianus & Geococcyx Velox Wild Status: Not Threatened Habitat: Arid dessert and shrub Country: United States, Mexico, and Central America Shelter: These birds nest 1-3 meters off the ground in low trees, shrubs, or cactus Life Span: 8 years Size: 2 feet in length; 8-15 ounces Details The genus Geococcyx consists of two species of bird: the greater roadrunner and the lesser roadrunner. They live in the arid climates of Southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central America. Though these birds can fly, they spend most of their time running from shrub to shrub. Roadrunners spend the entirety of their day hunting prey and dodging predators. It's a tough life out there in the wild! These birds eat insects, small reptiles and mammals, arachnids, snails, other birds, eggs, fruit, and seeds. One thing that these birds do not have to worry about is drinking water. They intake enough moisture through their diet and are able to secrete any excess salt build-up through glands in their eyes. This adaptation is common in sea birds as their main source of hydration is the ocean. The fact that roadrunners have adapted this trait as well goes to show how well they are suited for their environment. A roadrunner will mate for life and will travel in pairs, guarding their territory from other roadrunners. When taking care of the nest, both male and female take turns incubating eggs and caring for their young. The young will leave the nest after a couple weeks and will then learn foraging techniques for a few days until they are left to fend for themselves. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

352.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE TRIMORPHODON Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. and Zacatecas; through the Pacific lowlands and some dry interior valleys of Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua to SCOTT, NORMAN J., JR., AND ROY W. MCDIARMID. 1984. Tri- Guanacaste and Puntarenas provinces of northwestern Costa Rica. morpkodon. A record for Panamá (Boulenger, 1896) is not confirmed and prob- ably erroneous. Elevational range from sea level to 2600 m. Trimorphodon Cope • FOSSIL RECORD. See species accounts. Lyre Snakes • PERTINENT LITERATURE. McDiarmid and Scott (1970) re- Trimorphodon Cope, 1861:297, Type species, Lycodon lyro- viewed T. tau, and Gehlbach (1971) revised T. biscutatus-, see these phanes Cope, 1860, by original designation. and the species accounts for additional references. Eteirodipsas Jan, 1863:105. Type species, Dipsas biscutata Du- • KEY TO SPECIES, méril, Bibron, and Duméríl, 1854, by subsequent designation (Smith and Taylor, 1945; Mertens, 1952). Pole band on nape broad with a straight or slightly indented Hetaerodipsas Berg, 1901:90. Emendation of Eteirodipsas Jan. posterior border; most dorsal dark saddles confluent with dark markings on ventrals 7^ tau • CONTENT. TWO species are recognized: T biscutatus and T. Pale band on nape narrow and chevron or lyre shaped, posterior tau. border A or U-shaped; most dorsal dark saddles separated » DEnNlTlON AND DuGNOSis. A colubrid snake genus with lat- from dark spots on tips of ventrals T. biscutatus eral head scales fragmented, numerous, -

Taxonomic Hypotheses and the Biogeography of Speciation in the Tiger Whiptail Complex (Aspidoscelis Tigris: Squamata, Teiidae)

a Frontiers of Biogeography 2021, 13.2, e49120 Frontiers of Biogeography RESEARCH ARTICLE the scientific journal of the International Biogeography Society Taxonomic hypotheses and the biogeography of speciation in the Tiger Whiptail complex (Aspidoscelis tigris: Squamata, Teiidae) Tyler K. Chafin1* , Marlis R. Douglas1 , Whitney J.B. Anthonysamy1,2, Brian K. Sullivan3, James M. Walker1, James E. Cordes4, and Michael E. Douglas1 1 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas, 72701, USA; 2 St. Louis College of Pharmacy, 4588 Parkview Place, St. Louis, Missouri, 63110, USA; 3 School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences, P. O. Box 37100, Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona, 85069, USA; 4 Division of Mathematics and Sciences, Louisiana State University, Eunice, Louisiana, 70535, USA. *Corresponding author: Tyler K. Chafin, [email protected] Abstract Highlights Biodiversity in southwestern North America has a complex 1. Phylogeographies of vertebrates within the biogeographic history involving tectonism interspersed southwestern deserts of North America have been with climatic fluctuations. This yields a contemporary shaped by climatic fluctuations imbedded within pattern replete with historic idiosyncrasies often difficult broad geomorphic processes. to interpret when viewed from through the lens of modern ecology. The Aspidoscelis tigris (Tiger Whiptail) 2. The resulting synergism drives evolutionary processes, complex (Squamata: Teiidae) is one such group in which such as an expansion of within-species genetic taxonomic boundaries have been confounded by a series divergence over time. Taxonomic inflation often of complex biogeographic processes that have defined results (i.e., an increase in recognized taxa due to the evolution of the clade. To clarify this situation, arbitrary delineations), such as when morphological we first generated multiple taxonomic hypotheses, divergences fail to juxtapose with biogeographic which were subsequently tested using mitochondrial hypotheses. -

0189 Xantusia Henshawi.Pdf (296.1Kb)

189.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SAURIA: XANTUSIIDAE XANTUSIA HENSHA WI Catalogue of Am.erican Am.phihians and Reptiles. sequently (Van Denburgh, 1922) placed Z ablepsis henshavii in the synonymy ofX. henshawi Stejneger. Cope (1895b) described, LEE, JULIANC. 1976. Xantusia henshawi. but failed to name a supposedly new species of Xantusia. In a later publication (Cope, 1895c) he corrected the oversight, and named Xantusia picta. Van Denburgh (1916) synonymized Xantusia henshawi Stejneger picta with X. henshawi, and traced the complicated history of Granite night lizard the type-specimen . Xantusia henshawi Stejneger, 1893:467. Type-locality, "Witch • ETYMOLOGY.The specific epithet honors H. W. Henshaw. Creek, San Diego County, California." Holotype, U. S. Nat. According to Webb (1970), "The name bolsonae refers to the Mus. 20339, collected in May 1893 by H. W. Henshaw (Holo• geographic position of this race in a southern outlier of the type not seen by author). Bolson de Mapimi." Zablepsis henshavii: Cope, 1895a:758. See NOMENCLATURAL HISTORY. 1. Xantusia henshawi henshawi Stejnege •. Xantusia picta Cope, 1895c:859. Type-locality, "Tejon Pass, California," probably in error, corrected by Van Denburgh Xantusia henshawi Stejneger, 1893:467. See species account. Xantusia henshawi henshawi: Webb, 1970:2. First use of tri- (1916:14) to Poway, San Diego County, California. Holotype, nomial. Acad. Natur. Sci. Philadelphia 12881 (Malnate, 1971), prob• ably collected by Dr. Frank E. Blaisdell (see NOMENCLATURAL • DEFINITIONANDDIAGNOSIS. The mean snout-vent length HISTORY). in males is 56 mm., and in females 62 mm. Distinct post• • CONTENT. Two subspecies are recognized: henshawi and orbital stripes are usually absent, and the dorsal color pattern bolsonae. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

354.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE TRIMORPHODON TAU Catal4»gue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. • FOSSIL RECORD. None. SCOTT, NORMAN J., JR., AND ROY W. MCDIARMID. 1984. 7>t- • PERTINENT LITERATURE. McDiarmid and Scott (1970) sum- morphodon tau. marized the nomenclatura! history, biology, and zoogeography of the species. Bowler (1977) included a longevity record. Trimorphodon tau Cope • ETYMOLOGY. Cope (1870, 1886) used Greek letters to de- Mexican Lyre Snake scribe the patterns on the head and nape of three forms of Trimor- phodon. TcM refers to the T-shaped mark that extends transversely Eieirodipsas biscutata: Jan, 1863:105 (part). between the orbits and longitudinally to the end of the snout. The Trimorphodon tau Gipe, 1870:152. Type-locality, "western part term latifiiscia probably refers to the characteristic broad, dark of the Istlrmua of Tehiuuitepec, Mexico," in error; Sumichrast dorsal bands. (1882) stated that the bobtype came from near Quiotepec, Oasaca, between Tehuacán and Oaxaca. Holotype, U.S. Nat. Mus. 30338, juvenile, collected by Francois Sumicbraat, date 1. Trimorphodon tau tau Cope of collection unknown (examined by authors). Trimorphodon upsilon Cope, 1870:152. Type-locality, "Cuadalax- Trimorphodon tau Cope, 1870:152 (see species synonymy). ara. West Mexico." Holotype, U.S. Nat. Mus. 31358, male, Trimorphodon tau taw. Smith and Darling, 1952:85. collected by J. J. Major, date of collection unknown (examined Trimorphodon tau upsilon: Smith and Darling, 1952:85. by authors). • DEFINITION. Head cap usually pale to medium gray, with a Trimorphodon coUarit Cope, 1875:131. Type-locality, "Orizaba, light snout or prefrontal bar, complete interocular bar and variable Vera Cruz," México, in error; Sumichrast (1882) stated that light parietal markings. -

Fish and Wildlife

Appendix B Upper Middle Mainstem Columbia River Subbasin Fish and Wildlife Table 2 Wildlife species occurrence by focal habitat type in the UMM Subbasin, WA. -

Sauromalus Hispidus

ARTÍCULOS CIENTÍFICOS Cerdá-Ardura & Langarica-Andonegui 2018 - Sauromalus hispidus in Rasa Island- p 17-28 ON THE PRESENCE OF THE SPINY CHUCKWALLA SAUROMALUS HISPIDUS (STEJNEGER, 1891) IN RASA ISLAND, MEXICO PRESENCIA DEL CHACHORÓN ESPINOSO SAUROMALUS HISPIDUS (STEJNEGER, 1891) EN LA ISLA DE RASA, MÉXICO Adrián Cerdá-Ardura1* and Esther Langarica-Andonegui2 1Lindblad Expeditions/National Geographic. 2Facultad de Ciencias, Uiversidad Nacional Autónoma de México, CDMX, México. *Correspondence author: [email protected] Abstract.— In 2006 and 2013 two different individuals of the Spiny Chuckwalla (Sauromalus hispidus) were found on the small, flat, volcanic and isolated Rasa Island, located in the Midriff Region of the Gulf of California, Mexico. This species had never been recorded from Rasa Island prior to 2006. A new field study in 2014 revealed the presence of a single female chuckwalla inhabiting the Tapete Verde Valley, in the south-central part of the island, occupying a territory no bigger than 10000 m2. A scat analysis shows that the only food consumed by the animal is the Alkali Weed (Cressa truxilliensis) that forms patches of carpets in its habitat. The individual is in precarious condition, as it seems to starve on a seasonal basis, especially during El Niño cycles; also, it is missing fingers and toes, which appear to be intentional markings by amputation. We conclude that the two individuals were introduced to the island intentionally by humans. Keywords.— Chuckwalla, Gulf of California, Rasa Island. Resumen.— En 2006 y 2013 se encontraron dos individuos diferentes del cachorón de roca o chuckwalla espinoso (Sauromalus hispidus) en la pequeña, plana, volcánica y aislada isla Rasa, localizada en la Región de las Grandes Islas, en el Golfo de California, México. -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. Amphib. Reptile Conserv. | http://redlist-ARC.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Trade in Live Reptiles, Its Impact on Wild Populations, and the Role of the European Market

BIOC-06813; No of Pages 17 Biological Conservation xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bioc Review Trade in live reptiles, its impact on wild populations, and the role of the European market Mark Auliya a,⁎,SandraAltherrb, Daniel Ariano-Sanchez c, Ernst H. Baard d,CarlBrownd,RafeM.Browne, Juan-Carlos Cantu f,GabrieleGentileg, Paul Gildenhuys d, Evert Henningheim h, Jürgen Hintzmann i, Kahoru Kanari j, Milivoje Krvavac k, Marieke Lettink l, Jörg Lippert m, Luca Luiselli n,o, Göran Nilson p, Truong Quang Nguyen q, Vincent Nijman r, James F. Parham s, Stesha A. Pasachnik t,MiguelPedronou, Anna Rauhaus v,DannyRuedaCórdovaw, Maria-Elena Sanchez x,UlrichScheppy, Mona van Schingen z,v, Norbert Schneeweiss aa, Gabriel H. Segniagbeto ab, Ruchira Somaweera ac, Emerson Y. Sy ad,OguzTürkozanae, Sabine Vinke af, Thomas Vinke af,RajuVyasag, Stuart Williamson ah,1,ThomasZieglerai,aj a Department Conservation Biology, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Conservation (UFZ), Permoserstrasse 15, 04318 Leipzig, Germany b Pro Wildlife, Kidlerstrasse 2, 81371 Munich, Germany c Departamento de Biología, Universidad del Valle de, Guatemala d Western Cape Nature Conservation Board, South Africa e Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology,University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd, Lawrence, KS 66045, USA f Bosques de Cerezos 112, C.P. 11700 México D.F., Mexico g Dipartimento di Biologia, Universitá Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy h Amsterdam, The Netherlands