A House Is a Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Friend P2p

MY FRIEND P2P Music and Internet for the Modern Entrepreneur Lucas Pedersen Bachelor’s Thesis December 2010 Degree Program in Media Digital Sound and Commercial Music Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu Tampere University of Applied Sciences 2 ABSTRACT Tampere University of Applied Sciences Degree Program in Media Digital Sound and Commercial Music PEDERSEN, LUCAS: My Friend p2p – Music and Internet for the Modern Entrepreneur Bachelor’s thesis 81 pages December 2010 _______________________________________________________________ The music industry is undergoing an extensive transformation due to the digital revolution. New technologies such as the PC, the internet, and the iPod are empowering the consumer and the musician while disrupting the recording industry models. The aim of my thesis was to acknowledge how spectacular these new technologies are, and what kind of business structure shifts we can expect to see in the near future. I start by presenting the underlying causes for the changes and go on to studying the main effects they have developed into. I then analyze the results of these changes from the perspective of a particular entrepreneur and offer a business idea in tune with the adjustments in supply and demand. Overwhelmed with accessibility caused by democratized tools of production and distribution, music consumers are reevaluating recorded music in relation to other music products. The recording industry is shrinking but the overall music industry is growing. The results strongly suggest that value does not disappear, it simply relocates. It is important that both musicians and industry professionals understand what their customers value and how to provide them with precisely that. _______________________________________________________________ Key Words: Music business, digital revolution, internet, piracy, marketing. -

U-Vote Sity Center

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (1990s) Student Newspapers 4-24-1995 Current, April 24, 1995 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current1990s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, April 24, 1995" (1995). Current (1990s). 175. https://irl.umsl.edu/current1990s/175 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (1990s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDITORIAL The University of Missouri-St. See The Current's Top 10 quotes of the Louis will be asking your opin year. Did you make the list? ion on plans for a new U niver FEATURES U-Vote sity Center. See the Feature Take a look at [he reviews on the Features page (5) for more details. page (7)for two ofthelatestflicks to hit the theaters. SPORTS The Rivermen baseball team split two games in the first round of the playoffs against Washburn. Issue 825 UNIVERSITY .OF MISSOURI-ST. LOUIS April 24, 1995 ij .Titlow wins elec ion by 'lands ide ~weifel , Rauscher win for SCAclean sweep; .party plans to tackle 'Students as Customers' fly Jeremy Rutherford addition to the race, Anthony Guada, finished with winning with 354 votes. Pam White was second managing editor 19. with 23'4 votes , and another late addition, "For the vote to come down that strong, to win Lawrence Berry, picked up 78 votes. In just two short years, Beth Titlow has accom- by [that many] votes, is amazing," Titlow said. -

Clas of 2026 Woul Lik T Dedicat Thi Volum T Mr . Kath Curt

�� Clas� of 2026 woul� lik� t� dedicat� thi� volum� t� Mr�. Kath� Curt� W� than� Mr�. Curt� for helpin� u� t� paus� an� reflec� o� our strength�, joy�, an� struggle� aer suc� � demandin� year. W� hav� ha� t� adap� t� man� challenge� durin� thi� pandemi�, bu� reconnectin� wit� our value� an� eachother help� t� keep u� grounde� an� ope� t� findin� new meaning�. I� Gratitud�, Mr�. Daniell� Pec� an� M�. Perron�’� Sevent� Grad� Clas� Jun� 2021 1 I Believe in the Power of Music By: Carly Suessenbach I believe in the power of music. Music can help people in so many ways like when you are sad you can listen to happy music, if you can't sleep you can turn on calming music that doesn't have any lyrics, or you can put on sad music if you just want to let out a cry. Music can also motivate you or inspire you to do something. Music helps me by calming me down when I'm stressed, makes me happy when I am sad or angry, or sometimes I just listen to sad music because I just feel like it. Music also helps me fall asleep faster. When I listen to music I feel like I'm in a whole different world and in that world all my worries, problems and stress goes away and I feel happy. Music is important to me because a lot of songs have really deep meanings to them. Music inspires me to make my own music or learn to play the piano or guitar. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Anima Automata: On the Olympian Art of Song Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2f4304xv Author Porzak, Simon Lucas Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Anima Automata: On the Olympian Art of Song By Simon Lucas Porzak A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, Co-Chair Professor Barbara Spackman, Co-Chair Professor Pheng Cheah Professor Susan Schweik Spring 2014 Anima Automata: On the Olympian Art of Song © 2014, Simon Lucas Porzak 1 Abstract Anima Automata: On the Olympian Art of Song by Simon Lucas Porzak Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, Co-Chair Professor Barbara Spackman, Co-Chair Dominant explanations of the power of song, in musicology, sound studies, media theory, and our cultural mythologies about divas and pop singers, follow a Promethean trajectory: a singer wagers her originary humanity through an encounter with the machinery of music (vocal training, recording media, etc.); yet her song will finally carry an even more profound, immediate human meaning. Technology forms an accidental detour leading from humanity to more humanity. In an alternative, “Olympian” practice of singing, humanity and machinery constantly and productively contaminate each other. My readings, centering around the singing doll Olympia from Jacques Offenbach’s 1881 opera Les Contes d’Hoffmann , illuminate the affective and ethical consequences of the confrontation between Promethean and Olympian song. -

June 2019 2019 June Free

CELEBRATING The Park Press YEARS! JUNE 2019 ~ Positive news that matters ~ 12FREE Winter Park | Baldwin Park | College Park | Audubon Park | Maitland RESORT-STYLE RETIREMENT LIVING MEMBERSHIP* $149/MONTH 1 OF EACH INCLUDED PER MONTH • Couture Facial • Intense Pulsed Light Treatment (IPL) • Fractional Laser Treatment • Laser Hair Removal (any area) ® M O C . D M G N I D L I E Y . • Body Contouring/Fat Burning (truSculpt ) *12 month term & annual fee of $149 W W W RUTH HILL YEILDING, MD COUTUREMEDSPA.COM THEMAYFLOWER.COM | 407.672.1620 WINTER PARK • OVIEDO • OCOEE 88141 PRAD TPP 6/2019 For updated news, events and more, visit www.TheParkPress.com Runners And Walkers Race To Support Local Military At AdventHealth Watermelon 5k Runners, walkers and fitness enthusiasts of all ages will enjoy a patriotic celebration and summertime fun at the AdventHealth Watermelon 5k, Thursday, July 4 in Central Park in Downtown Winter Park. The 3.1-mile run/walk begins at 7:30 a.m. followed by a free kids’ run at 8:45 a.m. It’s an All-American-style celebration featuring a shady course, live music, ice-cold watermelon for all, free kids’ run, and the crowd favorite, the 13th Annual Watermelon Eating Contest judged by Florida’s Watermelon Queen. “AdventHealth is happy to sponsor this 5k in support of our military veterans. AdventHealth employs large numbers of veterans in all areas of the organization, from doctors and nurses to chaplains to senior executives. The discipline, dedication and leadership shown by our veteran employees are invaluable in carrying out AdventHealth’s mission,” said Sharon Line-Clary, the vice president of Runners and walkers will begin the 5k on Thursday, July 4 in downtown Winter Park at 7:30 a.m. -

DISCOGRAPHY YOAD NEVO Producer, Mixer

DISCOGRAPHY Zippelhaus 5a 20457 Hamburg Tel: 040 / 28 00 879 - 0 YOAD NEVO Fax: 040 / 28 00 879 - 28 producer, mixer mail: [email protected] Girls Aloud "Out of control"(2xUL, 2xIRE), "The Sound of Girls Aloud" (3xU, 1xEU, 1xIRE) Sugababes "Overload: The Singles Collection" (UK, IRE), "Three" (EU, 2xUK), "Angel with dirty faces" (EU, 3xUK) Bryan Adams "Room Service" (CAN) Platin Award Ronan Keating "Destination" (2xUK, 2xAUS) Sophie Ellis-Bextor "Murder on the dancefloor" (AUS), "Read my lips" (2xUK, EU, AUS) Boyzone "When the going gets tough" (UK) Sugababes "Overload: The Singles Collection" (DEN), "Three" (GER, SWI), "Angel with dirty faces" SWI, NLD) Sophie Ellis-Bextor "Murder on the dancefloor" (FRA) Gold Award Ronan Keating "Destination" (GER) Bryan Adams "Room Service" (GER, SWI, UK) P: Producer E: Engineer M: Mixer Ma: Mastering Mu: Musician R: Remixer Co-W: Co-Writer W: Writer ED: Editor Pro: Programmer A: Arrangement Year Artist Title Project Label Credit 2015 Stefanie Heinzmann Chance Of Rain Album Polydor/Island M Albumtrack on OS "Fifty Shades Universal Studios & Sia "Salted Wound" M of Grey" Republic Records "Glitter", "Electrify","Love Is The á Deux/Cosmos Say Lou Lou Albumtracks M Loneliest Place" Music 2014 Open Season Boombay Album Open Season Master Les Loups tba POPLABOR Rockcity P 2013 Left Boy Permanent Midnight Album inkl. Single Warner Music M Left Boy "Security Check" Single Warner Music M ferryhouse Brixton Boogie Love ain't just a word Single M productions Sia tba Album tba M Glasperlenspiel Nie vergessen Single Universal P, M Glasperlenspiel Grenzenlos Album incl. single Universal AddP, M 2012 Son of a kid tba M EMI/TEN Jonas Myrin Day of the battle Single EMI AddP, M Chima Stille Album incl. -

Jagjit Singh's

October, 2020 KATRINA’S SUPER HERO FILM IN TROUBLE MEET THE REAL HERO, SONU SOOD RANVEER SINGH’S MASTERPLAN ANUSHKA SHARMA BRAVE NEW WORLD HEROINES WHO MAKE A DIFFERENCE Volume 69 # October 2020 / ISSN NUMBER 0971-7277 October, 2020 KATRINA’S SUPER HERO FILM IN TROUBLE MEET THE REAL HERO, SONU SOOD RANVEER SINGH’S MASTERPLAN ANUSHKA SHARMA BRAVE NEW WORLD HEROINES WHO MAKE A DIFFERENCE PHOTOGRAPHS: TIBI CLENCI STYLING: ALLIA AL RUFAI HAIR: EARL SIMMS | MAKE-UP: LIZ PUGH DESTINATION PARTNER: VISIT BRUSSELS TRAVEL CO-ORDINATORS: 27 GLOBAL HOPPERS Dress: Maison Esve | Jewellery: Isharya Editor’s Choice Bollywood heroines 04have truly evolved, says the editor Celebrating 50 years 70 of YRF 08 42 Masala fix Fashion & lifestyle Imtiaz Ali feels all Shah Rukh Khan to Designer Shehla Khan 50 journeys happen within 08 make a comeback with 22 opens up on her Obituary: Johnny Sanki, Tiger Shroff to journey 54 Bakshi play a boxer in Ganpat, Obituary: Ashalata Salman Khan’s Tiger 3 Exclusives 55 Wabgaonkar to be shot in seven Exclusive cover story: Remembering SP countries and more grist 27 We take a look at the 56 Balasubrahmanyam from the rumour mill. women of style and Looking back with Preview substance who’re 60 affection at Jagjit Singh currently ruling the Your say Singer Leena Bose is industry 16 waiting for more hits Sonu Sood is the Readers send in Ritwik Bhowmik is happy 42 messiah of the masses 66 their rants 18 with the success of Alaya F is finding her Shatrughan Sinha’s 12 Bandish Bandits 46 own space 68 wacky witticisms olivesatyourtable.in Olives at your table INDIA @olivesatyourtable.in Olives at your table INDIA The content of this promotion campaign publication represents the views of the author only and is his/her sole responsibility. -

BOARD of ZONING APPEAL for the CITY of CAMBRIDGE GENERAL HEARING THURSDAY, JULY 30, 2015 7:00 P.M. in Senior Center 806 Massach

1 BOARD OF ZONING APPEAL FOR THE CITY OF CAMBRIDGE GENERAL HEARING THURSDAY, JULY 30, 2015 7:00 p.m. in Senior Center 806 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Constantine Alexander, Chair Timothy Hughes, Vice Chair Brendan Sullivan, Member Douglas Myers, Associate Member George S. Best, Associate Member Jim Monteverde, Associate Member Sean O'Grady, Zoning Specialist ____________________________ REPORTERS, INC. CAPTURING THE OFFICIAL RECORD 617.786.7783/617.639.0396 (Fax) www.reportersinc.com 2 I N D E X CASE PAGE BZA-006869-2015 -- 1350 Mass Avenue 7 BZA-006133-2015 -- 209 Broadway 203 BZA-006922-2015 -- 236 Walden Street 3 BZA-007147-2015 -- 40 Pemberton Street 264 BZA-007159-2015 -- 10 Fayerweather Street 274 BZA-007156-2015 -- 32 Hawthorn Street 290 BZA-007188-2015 -- 55 Magee Street 322 BZA-007185-2015 -- 81-93 Mt. Auburn Street 342 BZA-007226-2015 -- 114 Clifton Street 361 BZA-007211-2015 -- 35 Clay Street 368 BZA-007219-2015 -- 243 Hampshire Street 385 Case No. 10469 -- 9 Oakland Street 398 KeyWord Index 3 P R O C E E D I N G S * * * * * (7:00 p.m.) (Sitting Members Case BZA-006922-2015: Constantine Alexander, Timothy Hughes, Brendan Sullivan, Douglas Myers, George S. Best.) CONSTANTINE ALEXANDER: The Chair will call this meeting of the Zoning Board of Appeals to order. And as is our custom, we are going to start with continued cases. These are cases that are started at an earlier hearing and for one reason or another have been continued to this evening. The first case I'm going to call is No. -

The Business of Grime

RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR CULTURAL AND MEDIA ECONOMIES CAMEo CUTS #6 The Business of Grime Joy White CAMEo Cuts CAMEo Cuts is an occasional series that showcases reflections on cultural and media economies, written by CAMEo researchers, collaborators and affiliates. Contributions aim to be short, accessible and engage a wide audience. If you would like to propose an article for inclusion in CAMEo Cuts please email [email protected] Previous CAMEo Cuts editions, available via www.le.ac.uk/cameo Cuts #1, Mark Banks, What is Creative Justice?, June 2017 Cuts #2, Claire Squires, Publishing’s Diversity Deficit, June 2017 Cuts #3, Melissa Gregg, From Careers to Atmospheres, August 2017 Cuts #4, Julia Bennett, Crafting the Craft Economy, August 2017 Cuts #5, Richard E. Ocejo, Minding the Cool Gap: New Elites in Blue-Collar Service Work, November 2017 © CAMEo Research Institute for Cultural and Media Economies, University of Leicester, January 2018 The Business of Grime Joy White This sixth edition of CAMEo Cuts focusses on the emerging economy of Grime music. The music industry is a significant economic sector that ought to provide earning opportunities for a wide variety of young people who have the necessary skills, interests and talents. And yet, this sector has some of the lowest diversity rates in terms of ethnicity and class. By contrast, Grime, and the wider urban music economy, can offer a multiplicity of routes into the creative and cultural industries for diverse and disadvantaged groups. From its London origins, Grime has expanded regionally through the Eskimo Dance and Sidewinder events, and from Lord of the Mics MC clashes to the nascent Grime Originals events, the Grime economy has a national (UK) and international reach. -

Life Story Interviews Martin Redfern

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ‘Science and Religion: Exploring the Spectrum’ Life Story Interviews Martin Redfern Interviewed by Paul Merchant C1672/29 This transcript is copyright of the British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] IMPORTANT Access to this interview and transcript is for private research only. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators ([email protected]) The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C1672/29 Collection title: ‘Science and Religion: Exploring the Spectrum’ Life Story Interviews Interviewee’s surname: Redfern Title: Mr Interviewee’s forename: Martin Sex: Male Occupation: Science writer and BBC Date and place of birth: 18th July 1954, Rochester, radio science producer Kent, UK Mother’s occupation: teacher Father’s occupation: oil industry chemist Dates of recording, Compact flash cards used, tracks (from – to): 30/8/16 (track 1-2), 27/9/16 (track 3-7), 11/10/16 (track 8-11) Location of interview: Interviewee’s home in Shorne, Kent Name of interviewer: Paul Merchant Type of recorder: Marantz PMD661on compact flash Recording format : audio file 12 WAV 24 bit 48 kHz 2-channel Total no. -

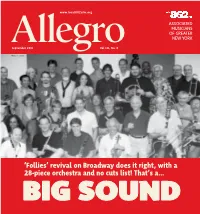

Revival on Broadway Does It Right, with a 28-Piece Orchestra and No Cuts List! That’S A… Big Sound N Your Union Staff

www.local802afm.org ASSOCIATED MUSICIANS OF GREATER NEW YORK AllegroSeptember 2011 Vol 111, No. 8 PHOTO: C. CROFT PHOTO: WALTER KARLING WALTER PHOTO: ‘Follies’ revival on Broadway does it right, with a 28-piece orchestra and no cuts list! That’s a… BIG SOUND n YOUR UNION STAFF NOVEM- UNION CALENDAR LOCAL 802 berSEPT. 2010 2011 Send information to Mikael Elsila at OFFICERS UNION REPS AND ORGANIZERS [email protected] Tino Gagliardi, President Claudia Copeland (Theatre) John O’Connor, Recording Vice President Bob Cranshaw (Jazz consultant) Thomas Olcott, Financial Vice President Karen Fisher (Concert) Marisa Friedman (Theatre, Teaching artists) EXECUTIVE BOARD JAZZ JAM lead to meaningful paid work. This event is free Shane Gasteyer (Organizing) Bud Burridge, Bettina Covo, Patricia There is a jazz jam on most Mondays at Local 802, and is sponsored by the Actors Work Program. Dougherty, Martha Hyde, Gail Kruvand, Bob Pawlo (Electronic media) from 7 to 9:30 p.m. Upcoming dates include Sept. Thursday, Sept. 22 at 5:30 p.m. in the Local 802 Maxine Roach, Andy Schwartz, Clint Richard Schilio (Club dates, Hotels) 12, Sept. 19 and Sept. 26. For more information, Sharman David Sheldon (Electronic media) club room. call Joe Petrucelli at the Jazz Foundation of Peter Voccola (Long Island) TRIAL BOARD America at (212) 245-3999, ext. 10, or e-mail Joe@ THEATRE COMMITTEE Todd Weeks (Jazz) Roger Blanc, Sara Cutler, Tony Gorruso, JazzFoundation.org. The Theatre Committee meets on Sept. 7 and Eugene Moye, Marilyn Reynolds, SICK PaY & HOSPITALIZATION FUND/ Sept. 21 at 5 p.m. in the Executive Board Room. -

Black Matters Science in Four Afrofuturist Literary Works

Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004 Tesi di Laurea Black Matters Science in Four Afrofuturist Literary Works Relatore Prof. Shaul Bassi Correlatore Prof. Marco Fazzini Laureando Elisabetta Artusi Matricola 844329 Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 Contents Introduction 1 1. What is Afrofuturism? 7 1.1 From Scientific Racism to Identity 14 1.2 Science and Racial Difference in Science Fiction 20 2. The Science of Afrofuturist Music 23 3. Nova 33 3.1 Race, Identity and Science Fiction: an Inside Perspective 33 3.2 Flying Inside a Nova 36 3.3 Digging Inside Nova 41 4. Lagoon 51 4.1 Science Fiction in Africa 51 4.2 New Neighbours 52 4.3 The Scientist Witch 57 4.4 Lagos Rhymes with Chaos 63 4.5 Speaking Lagosian 68 5. Recurrence Plot (and Other Time Travel Tales) 72 5.1 Experimenting with Science and Fiction 72 5.2 Between Fiction and Reality 74 5.3 A Quantum World 79 5.4 Boxes and Mirrors 85 6. A Killing in the Sun 90 6.1 Afrofuturism Reaches Africa 90 6.2 Africa Takes Back Control 92 6.3 Western Science vs African Magic 99 6.4 Taking Africa to Space 101 Conclusion 105 Bibliography 109 Introduction The definition of science fiction as a literary genre is a controversial subject among critics. When trying to trace the specific characteristics of the genre, they tend to disagree and contradict one another sometimes even resorting to tautologies that are not very useful in the analysis of the genre.