Quantifying the Mulligan River Pituri, Duboisia Hopwoodii ((F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

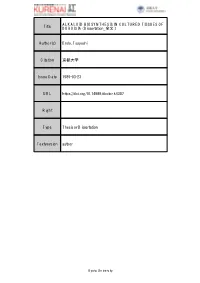

Title ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS in CULTURED TISSUES OF

ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN CULTURED TISSUES OF Title DUBOISIA( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Endo, Tsuyoshi Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 1989-03-23 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k4307 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion author Kyoto University ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN C;ULTURED TISSUES OF DUBOISIA . , . ; . , " 1. :'. '. o , " ::,,~./ ~ ~';-~::::> ,/ . , , .~ - '.'~ . / -.-.........."~l . ~·_l:""· .... : .. { ." , :: I i i , (, ' ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN CULTURED TISSUES OF DUBOISIA TSUYOSHIENDO 1989 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ----------1 CHAPTER I ALKALOID PRODUCTION IN CULTURED DUBOISIA TISSUES. INTRODUCTION ----------6 SECTION 1 Alkaloid Production and Plant Regeneration from ~ leichhardtii Calluses. ----------8 SECTION 2 Alkaloid Production in Cultured Roots of Three Species of Duboisia. ---------16 SECTION 3 Non-enzymatic Synthesis of Hygrine from Acetoacetic Acid and from Acetonedicar- boxylic Acid. ---------25 CHAPTER II SOMATIC HYBRIDIZATION OF DUBOISIA AND NICOTIANA. INTRODUCTION ---------35 SECTION 1 Establishment of an Intergeneric Hybrid Cell Line of ~ hopwoodii and ~ tabacum. ---------38 SECTION 2 Genetic Diversity Originating from a Single Somatic Hybrid Cell. ---------47 SECTION 3 Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Somatic Hybrids, D. leichhardtii + ~ tabacum ---------59 CONCLUSIONS ---------76 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ---------79 REFERENCES ---------80 PUBLICATIONS ---------90 ABBREVIATIONS BA 6-benzyladenine OAPI 4',6-diamino-2-phenylindoledihydrochloride EDTA ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid GC-MS gas chromatography - mass spectrometry -

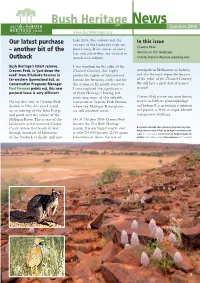

Autumn 2016 Bushheritage.Org.Au from the CEO Bush Heritage Australia Who We Are Twenty-Five Years Ago, a Small Group There Is So Much More to Do

BUSH TRACKS Bush Heritage Australia’s quarterly magazine for active conservation Maggie nose best Tracking feral cats Since naturalist John Young’s rediscovery Evidence suggests that feral cat density on of the population in 2013, a recovery the property is low, but there are at least two in Queensland team led by Bush Heritage Australia, and individuals prowling close to where Night Meet Maggie, a four-legged friend working ornithologists Dr Steve Murphy and Allan Parrots roost during the day. Just one feral hard to protect the world’s only known Burbidge, have been working tirelessly to cat that develops a taste for Night Parrots population of Night Parrots on our newest bring the species back from the brink of would be enough to drive this population, reserve, secured recently with the help of extinction. The first step – to purchase the and possibly the species, into extinction. Bush Heritage supporters. land where this elusive population live – Continued on page 3 has been taken, thanks to Bush Heritage It’s 3am. The sun won’t appear for hours, donors, and the reserve is now under In this issue but for Mark and Glenys Woods and their intensive and careful management. 4 Happy 10th birthday Cravens Peak ever-loyal companion Maggie, work is 8 Discovering the Dugong about to begin. The priority since the purchase has been 9 By the light of the moon managing threats to the Night Parrot After a quick breakfast they jump in the ute 10 Apples and androids: The future population, chiefly feral cats. of wildlife monitoring? and drive 45 minutes to the secret location 11 Bob Brown’s photographic journey in western Queensland where the world’s Mark Woods and trusty companion Maggie are of our reserves only known population of Night Parrots helping in the fight to protect the Night Parrot 12 Yourka family camp has survived. -

Cravens Peak Scientific Study Report

Geography Monograph Series No. 13 Cravens Peak Scientific Study Report The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. Brisbane, 2009 The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. is a non-profit organization that promotes the study of Geography within educational, scientific, professional, commercial and broader general communities. Since its establishment in 1885, the Society has taken the lead in geo- graphical education, exploration and research in Queensland. Published by: The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. 237 Milton Road, Milton QLD 4064, Australia Phone: (07) 3368 2066; Fax: (07) 33671011 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rgsq.org.au ISBN 978 0 949286 16 8 ISSN 1037 7158 © 2009 Desktop Publishing: Kevin Long, Page People Pty Ltd (www.pagepeople.com.au) Printing: Snap Printing Milton (www.milton.snapprinting.com.au) Cover: Pemberton Design (www.pembertondesign.com.au) Cover photo: Cravens Peak. Photographer: Nick Rains 2007 State map and Topographic Map provided by: Richard MacNeill, Spatial Information Coordinator, Bush Heritage Australia (www.bushheritage.org.au) Other Titles in the Geography Monograph Series: No 1. Technology Education and Geography in Australia Higher Education No 2. Geography in Society: a Case for Geography in Australian Society No 3. Cape York Peninsula Scientific Study Report No 4. Musselbrook Reserve Scientific Study Report No 5. A Continent for a Nation; and, Dividing Societies No 6. Herald Cays Scientific Study Report No 7. Braving the Bull of Heaven; and, Societal Benefits from Seasonal Climate Forecasting No 8. Antarctica: a Conducted Tour from Ancient to Modern; and, Undara: the Longest Known Young Lava Flow No 9. White Mountains Scientific Study Report No 10. -

Duboisia Myoporoides R.Br. Family: Solanaceae Brown, R

Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants - Online edition Duboisia myoporoides R.Br. Family: Solanaceae Brown, R. (1810) Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae : 448. Type: New South Wales, Port Jackson, R. Brown, syn: BM, K, MEL, NSW, P. (Fide Purdie et al. 1982.). Common name: Soft Corkwood; Mgmeo; Poison Corkwood; Poisonous Corkwood; Corkwood Tree; Eye-opening Tree; Eye-plant; Duboisia; Yellow Basswood; Elm; Corkwood Stem Seldom exceeds 30 cm dbh. Bark pale brown, thick and corky, blaze usually darkening to greenish- brown on exposure. Leaves Leaf blades about 4-12 x 0.8-2.5 cm, soft and fleshy, indistinctly veined. Midrib raised on the upper surface. Flowers. © G. Sankowsky Flowers Small bell-shaped flowers present during most months of the year. Calyx about 1 mm long, lobes short, less than 0.5 mm long. Corolla induplicate-valvate in the bud. Induplicate sections of the corolla and inner surfaces of the corolla lobes clothed in somewhat matted, stellate hairs. Corolla tube about 4 mm long, lobes about 2 mm long. Fruit Fruits globular, about 6-8 mm diam. Seed and embryo curved like a banana or sausage. Seed +/- reniform, about 3-3.5 x 1 mm. Testa reticulate. Habit, leaves and flowers. © Seedlings CSIRO Cotyledons narrowly elliptic to almost linear, about 5-8 mm long. First pair of true leaves obovate, margins entire. At the tenth leaf stage: leaf blade +/- spathulate, apex rounded, base attenuate; midrib raised in a channel on the upper surface; petiole with a ridge down the middle. Seed germination time 31 to 264 days. Distribution and Ecology Occurs in CYP, NEQ, CEQ and southwards as far as south-eastern New South Wales. -

Report to Office of Water Science, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane

Lake Eyre Basin Springs Assessment Project Hydrogeology, cultural history and biological values of springs in the Barcaldine, Springvale and Flinders River supergroups, Galilee Basin and Tertiary springs of western Queensland 2016 Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation Prepared by R.J. Fensham, J.L. Silcock, B. Laffineur, H.J. MacDermott Queensland Herbarium Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 © The Commonwealth of Australia 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI or the Commonwealth, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5725 Citation Fensham, R.J., Silcock, J.L., Laffineur, B., MacDermott, H.J. -

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species The first half of the color plates (Plates 1–8) shows a selection of phytochemically prominent solanaceous species, the second half (Plates 9–16) a selection of convol- vulaceous counterparts. The scientific name of the species in bold (for authorities see text and tables) may be followed (in brackets) by a frequently used though invalid synonym and/or a common name if existent. The next information refers to the habitus, origin/natural distribution, and – if applicable – cultivation. If more than one photograph is shown for a certain species there will be explanations for each of them. Finally, section numbers of the phytochemical Chapters 3–8 are given, where the respective species are discussed. The individually combined occurrence of sec- ondary metabolites from different structural classes characterizes every species. However, it has to be remembered that a small number of citations does not neces- sarily indicate a poorer secondary metabolism in a respective species compared with others; this may just be due to less studies being carried out. Solanaceae Plate 1a Anthocercis littorea (yellow tailflower): erect or rarely sprawling shrub (to 3 m); W- and SW-Australia; Sects. 3.1 / 3.4 Plate 1b, c Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade): erect herbaceous perennial plant (to 1.5 m); Europe to central Asia (naturalized: N-USA; cultivated as a medicinal plant); b fruiting twig; c flowers, unripe (green) and ripe (black) berries; Sects. 3.1 / 3.3.2 / 3.4 / 3.5 / 6.5.2 / 7.5.1 / 7.7.2 / 7.7.4.3 Plate 1d Brugmansia versicolor (angel’s trumpet): shrub or small tree (to 5 m); tropical parts of Ecuador west of the Andes (cultivated as an ornamental in tropical and subtropical regions); Sect. -

Bushtracks Bush Heritage Magazine | Summer 2019

bushtracks Bush Heritage Magazine | Summer 2019 Outback extremes Darwin’s legacy Platypus patrol Understanding how climate How a conversation beneath Volunteers brave sub-zero change will impact our western gimlet gums led to the creation temperatures to help shed light Queensland reserves. of Charles Darwin Reserve. on the Platypus of the upper Murrumbidgee River. Bush Heritage acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the places in which we live, work and play. We recognise and respect the enduring relationship they have with their lands and waters, and we pay our respects to elders, past and present. CONTRIBUTORS 1 Ethabuka Reserve, Qld, after rains. Photo by Wayne Lawler/EcoPix Chris Grubb Clare Watson Dr Viki Cramer Bron Willis Amelia Caddy 2 DESIGN Outback extremes Viola Design COVER IMAGE Ethabuka Reserve in far western Queensland. Photo by Lachie Millard / 8 The Courier Mail Platypus control This publication uses 100% post- 10 consumer waste recycled fibre, made Darwin’s legacy with a carbon neutral manufacturing process, using vegetable-based inks. BUSH HERITAGE AUSTRALIA T 1300 628 873 E [email protected] 13 W www.bushheritage.org.au Parting shot Follow Bush Heritage on: few years ago, I embarked on a scientific they describe this work reminds me that we are all expedition through Bush Heritage’s Ethabuka connected by our shared passion for the bush and our Aa Reserve, which is located on the edge of the dedication to seeing healthy country, protected forever. Simpson Desert, in far western Queensland. We were prepared for dry conditions and had packed ten Over the past 27 years, this same passion and days’ worth of water, but as it happened, our visit to dedication has seen Bush Heritage grow from strength- Ethabuka coincided with a rare downpour – the kind to-strength through two evolving eras of leadership of rain that transforms desert landscapes. -

Management Plan for the South Australian Lake Eyre Basin Fisheries

MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN LAKE EYRE BASIN FISHERIES Part 1 – Commercial and recreational fisheries Part 2 – Yandruwandha Yawarrawarrka Aboriginal traditional fishery Approved by the Minister for Agriculture, Food and Fisheries pursuant to section 44 of the Fisheries Management Act 2007. Hon Gail Gago MLC Minister for Agriculture, Food and Fisheries 1 March 2013 Page 1 of 118 PIRSA Fisheries & Aquaculture (A Division of Primary Industries and Regions South Australia) GPO Box 1625 ADELAIDE SA 5001 www.pir.sa.gov.au/fisheries Tel: (08) 8226 0900 Fax: (08) 8226 0434 © Primary Industries and Regions South Australia 2013 Disclaimer: This management plan has been prepared pursuant to the Fisheries Management Act 2007 (South Australia) for the purpose of the administration of that Act. The Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA (and the Government of South Australia) make no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this management plan or as to the suitability of that information for any particular purpose. Use of or reliance upon information contained in this management plan is at the sole risk of the user in all things and the Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA (and the Government of South Australia) disclaim any responsibility for that use or reliance and any liability to the user. Copyright Notice: This work is copyright. Copyright in this work is owned by the Government of South Australia. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth), no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission of the Government of South Australia. -

Abhf Summer Nl 05

Bush Heritage News Summer 2005 ABN 78 053 639 115 www.bushheritage.org Lake Eyre.The colours and the In this issue Our latest purchase vastness of the landscape took my Cravens Peak – another bit of the breath away. Rich ochres of every hue and cobalt-blue sky seemed to Anchors in the landscape Outback stretch into infinity. Charles Darwin Reserve weeding bee Bush Heritage’s latest reserve, I was standing on the edge of the Cravens Peak, is ‘just down the Channel Country, that highly metropolitan Melbourne or Sydney) road’ from Ethabuka Reserve in productive region of Queensland and also the most expensive because far-western Queensland but, as famous for fattening cattle, and for of the ‘value’ of the Channel Country. Conservation Programs Manager this reason so far poorly reserved. We still have a great deal of money Paul Foreman points out, this new I contemplated the significance to raise! pastoral lease is very different of Bush Heritage’s buying and protecting some of this valuable Cravens Peak is now our most diverse On my first visit to Cravens Peak ecosystem at Cravens Peak Station, reserve, in both its geomorphology Station in May this year I stood where the Mulligan River plains and biology. It is an exciting acquisition on an outcrop of the Toko Range are still relatively intact. and presents us with an unprecedented and gazed over the source of the management challenge. Mulligan River.This is one of the On 31 October 2005 Cravens Peak headwaters of the immense Cooper became the 21st Bush Heritage Creek system that braids its way reserve. -

Redalyc.Growth and Nutrient Uptake Patterns in Plants of Duboisia Sp

Semina: Ciências Agrárias ISSN: 1676-546X [email protected] Universidade Estadual de Londrina Brasil Cagliari Fioretto, Conrado; Tironi, Paulo; Pinto de Souza, José Roberto Growth and nutrient uptake patterns in plants of Duboisia sp Semina: Ciências Agrárias, vol. 37, núm. 4, julio-agosto, 2016, pp. 1883-1895 Universidade Estadual de Londrina Londrina, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=445749546016 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative DOI: 10.5433/1679-0359.2016v37n4p1883 Growth and nutrient uptake patterns in plants of Duboisia sp Crescimento e marcha de absorção de nutrientes em plantas de Duboisia sp Conrado Cagliari Fioretto1*; Paulo Tironi2; José Roberto Pinto de Souza3 Abstract Characterizing growth and nutrient uptake is important for the establishment of plant cultivation techniques that aim at high levels of production. The culturing of Duboisia sp., although very important for world medicine, has been poorly studied in the field, since the cultivation of this plant is restricted to a few regions. The objective of this paper is to characterize growth and nutrient absorption during development in Duboisia sp. under a commercial cultivation system, and in particular to assess the distribution of dry matter and nutrients in the leaves and branches. Our work was performed on a commercial production farm located in Arapongas, Paraná, Brazil, from March 2009 to February 2010. A total of 10 evaluations took place at approximately 10-day intervals, starting 48 days after planting and ending at harvesting, 324 days after planting. -

The Politics of Expediency Queensland

THE POLITICS OF EXPEDIENCY QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT IN THE EIGHTEEN-NINETIES by Jacqueline Mc0ormack University of Queensland, 197^1. Presented In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts to the Department of History, University of Queensland. TABLE OP, CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION SECTION ONE; THE SUBSTANCE OP POLITICS CHAPTER 1. The Men of Politics 1 CHAPTER 2. Politics in the Eighties 21 CHAPTER 3. The Depression 62 CHAPTER 4. Railways 86 CHAPTER 5. Land, Labour & Immigration 102 CHAPTER 6 Separation and Federation 132 CHAPTER 7 The Queensland.National Bank 163 SECTION TWO: THE POLITICS OP REALIGNMENT CHAPTER 8. The General Election of 1888 182 CHAPTER 9. The Coalition of 1890 204 CHAPTER 10. Party Organization 224 CHAPTER 11. The Retreat of Liberalism 239 CHAPTER 12. The 1893 Election 263 SECTION THREE: THE POLITICS.OF EXPEDIENCY CHAPTER 13. The First Nelson Government 283 CHAPTER Ik. The General Election of I896 310 CHAPTER 15. For Want of an Opposition 350 CHAPTER 16. The 1899 Election 350 CHAPTER 17. The Morgan-Browne Coalition 362 CONCLUSION 389 APPENDICES 394 BIBLIOGRAPHY 422 PREFACE The "Nifi^ties" Ms always" exercised a fascination for Australian historians. The decade saw a flowering of Australian literature. It saw tremendous social and economic changes. Partly as a result of these changes, these years saw the rise of a new force in Australian politics - the labour movement. In some colonies, this development was overshadowed by the consolidation of a colonial liberal tradition reaching its culmination in the Deakinite liberalism of the early years of the tlommdhwealth. Developments in Queensland differed from those in the southern colonies. -

100 the SOUTH-WEST CORNER of QUEENSLAND. (By S

100 THE SOUTH-WEST CORNER OF QUEENSLAND. (By S. E. PEARSON). (Read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, August 27, 1937). On a clear day, looking westward across the channels of the Mulligan River from the gravelly tableland behind Annandale Homestead, in south western Queensland, one may discern a long low line of drift-top sandhills. Round more than half the skyline the rim of earth may be likened to the ocean. There is no break in any part of the horizon; not a landmark, not a tree. Should anyone chance to stand on those gravelly rises when the sun was peeping above the eastem skyline they would witness a scene that would carry the mind at once to the far-flung horizons of the Sahara. In the sunrise that western region is overhung by rose-tinted haze, and in the valleys lie the purple shadows that are peculiar to the waste places of the earth. Those naked, drift- top sanddunes beyond the Mulligan mark the limit of human occupation. Washed crimson by the rising sun they are set Kke gleaming fangs in the desert's jaws. The Explorers. The first white men to penetrate that line of sand- dunes, in south-western Queensland, were Captain Charles Sturt and his party, in September, 1845. They had crossed the stony country that lies between the Cooper and the Diamantina—afterwards known as Sturt's Stony Desert; and afterwards, by the way, occupied in 1880, as fair cattle-grazing country, by the Broad brothers of Sydney (Andrew and James) under the run name of Goyder's Lagoon—and the ex plorers actually crossed the latter watercourse with out knowing it to be a river, for in that vicinity Sturt describes it as "a great earthy plain." For forty miles one meets with black, sundried soil and dismal wilted polygonum bushes in a dry season, and forty miles of hock-deep mud, water, and flowering swamp-plants in a wet one.