Mass of Creation Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saints Catholic Church

Gathering From Ashes to the Living Font Kyrie First Reading Gn 9:8-15 God said to Noah and to his sons with him: “See, I am now establishing my covenant with you and your descendants after you and with every living creature that was with you: all the birds, and the various tame and wild animals that were with you and came out of the ark. I will establish my covenant with you, that never again shall all bodily creatures be destroyed by the waters of a flood; there shall not be another flood to devastate the earth.” God added: “This is the sign that I am giving for all ages to come, of the covenant between me and you and every living creature with you: I set my bow in the clouds to serve as a sign of the covenant between me and the earth. When I bring clouds over the earth, and the bow appears in the clouds, I will recall the covenant I have made between me and you and all living beings, so that the waters shall never again become a flood to destroy all mortal beings.” Responsorial Psalm Psalm 25 To you, O Lord Second Reading 1 Pt 3:18-22 Beloved: Christ suffered for sins once, the righteous for the sake of the unrighteous, that he might lead you to God. Put to death in the flesh, 2 he was brought to life in the Spirit. In it he also went to preach to the spirits in prison, who had once been disobedient while God patiently waited in the days of Noah during the building of the ark, in which a few persons, eight in all, were saved through water. -

Saints Catholic Church

Gathering How Good Lord to Be Here Kyrie First Reading Gn 22:1-2, 9a, 10-13, 15-18 God put Abraham to the test. He called to withhold from me your own beloved son.” him, “Abraham!” “Here I am!” he replied. As Abraham looked about, he spied a ram Then God said: “Take your son Isaac, your caught by its horns in the thicket. So he only one, whom you love, and go to the went and took the ram and offered it up as land of Moriah. There you shall offer him a holocaust in place of his son. up as a holocaust on a height that I will point out to you.” Again the LORD’s messenger called to Abraham from heaven and said: “I swear When they came to the place of which God by myself, declares the LORD, that because had told him, Abraham built an altar there you acted as you did in not withholding and arranged the wood on it. Then he from me your beloved son, I will bless you reached out and took the knife to slaughter abundantly and make your descendants as his son. countless as the stars of the sky and the But the LORD’s messenger called to him sands of the seashore; your descendants from heaven, “Abraham, Abraham!” “Here shall take possession of the gates of their I am!” he answered. “Do not lay your hand enemies, and in your descendants all the on the boy,” said the messenger. “Do not nations of the earth shall find blessing— do the least thing to him. -

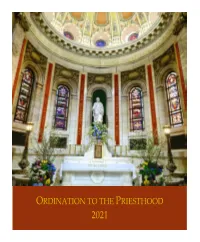

ORDINATION 2021.Pdf

WELCOME TO THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL Restrooms are located near the Chapel of Saint Joseph, and on the Lower Level, which is acces- sible via the stairs and elevator at either end of the Narthex. The Mother Church for the 800,000 Roman Catholics of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, the Cathedral of Saint Paul is an active parish family of nearly 1,000 households and was designated as a National Shrine in 2009. For more information about the Cathedral, visit the website at www.cathedralsaintpaul.org ARCHDIOCESE OF SAINT PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA Cover photo by Greg Povolny: Chapel of Saint Joseph, Cathedral of Saint Paul 2 Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis Ordination to the Priesthood of Our Lord Jesus Christ E Joseph Timothy Barron, PES James Andrew Bernard William Duane Duffert Brian Kenneth Fischer David Leo Hottinger, PES Michael Fredrik Reinhardt Josh Jacob Salonek S May 29, 2021 ten o’clock We invite your prayerful silence in preparation for Mass. ORGAN PRELUDE Dr. Christopher Ganza, organ Vêpres du commun des fêtes de la Sainte Vierge, op. 18 Marcel Dupré Ave Maris Stella I. Sumens illud Ave Gabrielis ore op. 18, No. 6 II. Monstra te esse matrem: sumat per te preces op. 18, No. 7 III. Vitam praesta puram, iter para tutum: op. 18, No. 8 IV. Amen op. 18, No. 9 3 HOLY MASS Most Rev. Bernard A. Hebda, Celebrant THE INTRODUCTORY RITES INTROITS Sung as needed ALL PLEASE STAND Priests of God, Bless the Lord Peter Latona Winner, Rite of Ordination Propers Composition Competition, sponsored by the Conference of Roman Catholic Cathedral Musicians (2016) ANTIPHON Cantor, then Assembly; thereafter, Assembly Verses Daniel 3:57-74, 87 1. -

When We Listen to a Piece of Music Performed by an Orchestra We

hen we listen to a piece of music performed by an orchestra we hear the melody, accompaniment, countermelodies and a whole W range of sounds that add richness and depth to the piece. But to understand the essence of a musical composition, we would start with the SING TO THE melody. The melody is the starting point for understanding the entire com- position. LORD: This article is like the melody line of a musical piece. In this case the full musical composition is the document, Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine MUSIC IN Worship. This document, which is a revision of the 1972 document, Music in Catholic Worship, was approved by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops on November 14, 2007. It provides current guidelines for DMNE those who prepare the liturgy. Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship should be read in its entirety to WORSHIP be fully appreciated. Yet how many liturgical documents, books, magazines, and other publications sit on desks and coffee tables waiting to be read by A SUMMARY OF THE USCCB people with good intentions but with little time? DOCUMENT ON MUSIC This article is a summary of what is contained in Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship. It is hoped that "hearing" the melody will give the reader the basic information found in the full composition. The numbers refer- Rev. ThomasB. lwanowski enced and the headings in this article correspond to the actual document. Capitalizations follow the style used in the document. Pastor I. WHY WE SING Our Lady of Czestochowa Liturgy uses words, gestures, signs, and symbols to proclaim the action of Jersey City, New Jersey God in our life and to give worship and praise to God. -

Mysterium Fidei! the Memorial Acclamation and Its Reception in French, English and Polish Missals

Liturgia Sacra 25 (2019), nr 1, s. 69–98 DOI: 10.25167/ls.1000 FERGUS RYAN OP Pontificio Istituto Liturgico, Roma ORCID 0000-0003-1595-7991 Mysterium fidei! The Memorial Acclamation and its reception in French, English and Polish Missals The acclamation after the consecration, commonly termed in English the “Me- morial Acclamation”, was introduced into the Roman Rite of Mass in 1968. Its introduction followed the encouragement of the Council Fathers less than five years earlier for the faithful to participate actively in the liturgy with acclamations1. The implementation of the memorial acclamation either in Latin or in spoken languages was not so straightforward, nor may it be considered complete today. A review of the introduction and implementation of a new people’s acclamation reveals how a change in the liturgy from the Holy See was received and how reception in some regions and languages seems to have influenced the reception elsewhere. Such a re- view may assist future development of the acclamation. 1. Singing after the consecration – a brief history The practice of singing the Benedictus phrase from the Sanctus after the consecra- tion of the bread and wine in the Roman Canon stretches back some centuries before the Second Vatican Council. The first edition of the Ceremonial of Bishops directed the Benedictus to be sung after the consecration at solemn pontifical Masses, not before the consecration: «Chorus prosequitur cantum usq. ad [Benedictus] exclusive […]. Elevato Sacramento, chorus prosequitur cantum [Benedictus, qui venit, &c]»2. The 1 Cf. SACROSANCTUM CONCILIUM OECUMENICUM VATICANUM II, Constitutio de sacra liturgia «Sacro- sanctum Concilium» (4 Decembris 1963), AAS 56 (1964), 108. -

The Memorial Acclamations Kristopher W

The Memorial Acclamations Kristopher W. Seaman The Memorial Acclamations In the face of death, God raised are part of the Eucharistic Christ Jesus from the dead to Prayer that the priest celebrant new life. The three acclamations and the liturgical assembly pray above go one step further than together. This is important, simply stating the mystery of because those in the liturgi- faith or the Paschal Mystery, cal assembly acclaim what the they acknowledge that we too priest celebrant proclaimed in are called to life made new. In the Eucharistic Prayer. Liturgy death, in sin, in pain and suf- is dialogical, that is, it is a dia- fering, God will bring about logue. A proclamation is usu- life. For example, the third ally followed by an acclamation. acclamation ends with “you This models our life as disci- have set us free.” As disciples, ples. God moves in liturgy, God we are given the nourishment dwells in our lives and calls us, of Christ’s own Body and Blood imperfect as we are, to grow in that brings new life and trans- holiness that only God can give. formation. This transformation is God’s liberating self given The Memorial Acclamation follows the Institution nar- to us through and in Eucharist. rative — the words Jesus used at the Last Supper over bread Perhaps the most known Memorial Acclamation is not and wine. This acclamation therefore, is our response to God’s listed above. “Christ has died, / Christ is risen, / Christ will coming to dwell among us, particularly in the transformation come again.” This particular acclamation was added some of bread and wine into Christ’s Body and Blood. -

Third Edition of the Roman Missal 5 Minute Catechesis Segment 1 Introduction to the Roman Missal

THIRD EDITION OF THE ROMAN MISSAL 5 MINUTE CATECHESIS SEGMENT 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE ROMAN MISSAL This is the rst segment of brief catechetical presentations on the Third Edition of the Roman Missal. When presenting Segment 1 it will be helpful to have the Lectionary, the Book of the Gospels and the Sacramentary for display. Recommendations for use of these segments: • Presented by the pastor or other liturgical minister before the opening song of Mass • Incorporated into the homily • Put in the bulletin • Distributed as a handout at Mass • Used as material for small group study on the liturgy • Presented at meetings, music rehearsals, parish gatherings Outline of Segment One What is the Roman Missal? • Three main books: Lectionary, Book of the Gospels; Book of Prayers Why do we need a new missal? • New rites/rituals/prayers • New prayer texts for newly canonized saints • Needed clari cations or corrections in the text Translations • Missal begins with a Latin original • Translated into language of the people to enable participation • New guidelines stress a more direct, word for word translation • Hope to recapture what was lost in translation THIRD EDITION OF THE ROMAN MISSAL 5 MINUTE CATECHESIS SEGMENT 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE ROMAN MISSAL What is the Roman Missal and why are we are composed for use at the liturgy in which we going to have a new one? honor them. Secondly, as new rituals are developed or revised, such as the Rite of Christian Initiation of When Roman Catholics Adults, there is a need for these new prayers to be celebrate Mass, all included in the body of the missal, and lastly, when the prayer texts, the particular prayers or directives are used over time, readings from Scripture, it can become apparent that there is a need for and the directives that adjustment to the wording for clari cation or for tell us how Mass is to be accuracy. -

The Mystery of the Mass: from “Greeting to Dismissal”

The Mystery of the Mass: from “Greeting to Dismissal” Deacon Modesto R. Cordero Director Office of Worship [email protected] “Many Catholics have yet to understand what they are doing when they gather for Sunday worship or why liturgical participation demands social responsibility.” Father Keith Pecklers., S.J. Professor of liturgical history at the Pontifical Liturgical Institute of Saint’ Anselmo in Rome PURPOSE Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (SC) ◦ Second Vatican Council – December 4, 1963 ◦ Eucharist is the center of the life of the Church ◦ Called for the reformation of the liturgical rites ◦ Instruction of the faithful Full conscious and active participation Their right and duty by baptism (SC14) ◦ Revised for the 3rd time (English translation) Advent 2011 – Roman Missal The definition … “Mass” is … The Eucharist or principal sacramental celebration of the Church. Established by Jesus Christ at the Last Supper, in which the mystery of our salvation through participation in the sacrificial death and glorious resurrection of Christ is renewed and accomplished. The Mass renews the paschal sacrifice of Christ as the sacrifice offered by the Church. Name … “Holy Mass” from the Latin ‘missa’ - concludes with the sending forth ‘missio’ [or “mission”] of the faithful The Lord’s Supper The Celebration of the Memorial of the Lord The Eucharistic Sacrifice - Jesus is implanted in our hearts Mystical Body of Christ “Where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in their midst” (Mt 18:20) -

First Sunday of Advent November 29, 2020 Introductory Rites Gathering Awake to the Day

1 First Sunday of Advent November 29, 2020 Introductory Rites Gathering Awake to the Day 2 Penitential Act Gloria 3 Liturgy of the Word First Reading Isaiah 63:16b-17, 19b; 64:2-7 / 2 You, Lord, are our father, our redeemer you are named forever. Why do you let us wander, O Lord, from your ways, and harden our hearts so that we fear you not? Return for the sake of your servants, the tribes of your heritage. Oh, that you would rend the heavens and come down, with the mountains quaking before you, while you wrought awesome deeds we could not hope for, such as they had not heard of from of old. No ear has ever heard, no eye ever seen, any God but you doing such deeds for those who wait for him. Would that you might meet us doing right, that we were mindful of you in our ways! Behold, you are angry, and we are sinful; all of us have become like unclean people, all our good deeds are like polluted rags; we have all withered like leaves, and our guilt carries us away like the wind. There is none who calls upon your name, who rouses himself to cling to you; for you have hidden your face from us and have delivered us up to our guilt. Yet, O Lord, you are our father; we are the clay and you the potter; we are all the work of your hands. 4 Responsorial Psalm Second Reading 1 Corinthians 1:3-9 Brothers and sisters: Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. -

The Thirtieth Sunday in Ordinary Time Sts

The Thirtieth Sunday in Ordinary Time Sts. Martha, Mary, and Lazarus Catholic Church October 25th, 2020 Introductory Rites Entrance Antiphon: Psalm 104:3-4 Let the hearts that seek the Lord rejoice; turn to the Lord and his strength; constantly seek his face. Entrance Hymn: O God, Our Help in Ages Past Greeting Penitential Rite Gloria Liturgy of the Word 1st Reading Exodus 22:20-26 Thus says the LORD: "You shall not molest or oppress an alien, for you were once aliens yourselves in the land of Egypt. You shall not wrong any widow or orphan. If ever you wrong them and they cry out to me, I will surely hear their cry. My wrath will flare up, and I will kill you with the sword; then your own wives will be widows, and your children orphans. "If you lend money to one of your poor neighbors among my people, you shall not act like an extortioner toward him by demanding interest from him. If you take your neighbor's cloak as a pledge, you shall return it to him before sunset; for this cloak of his is the only covering he has for his body. What else has he to sleep in? If he cries out to me, I will hear him; for I am compassionate." Responsorial Psalm Psalm 18:2-3, 3-4, 47, 51 V. I love you, O LORD, my strength, O LORD, my rock, my fortress, my deliverer. V. My God, my rock of refuge, my shield, the horn of my salvation, my stronghold! Praised be the LORD, I exclaim, and I am safe from my enemies. -

NUPTIAL MASS MUSIC PLANNING WORKSHEET Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish

NUPTIAL MASS MUSIC PLANNING WORKSHEET Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish Overall principles to remember in considering your wedding music: 1. In the Roman Catholic Nuptial Liturgy, every effort should be made to involve the Assembly in “full, conscious, and active participation” in the Liturgy, including elements of the music. 2. The text of the music chosen should ideally speak of the love between husband and wife as a reflection of God’s love for us, his Church. Secular love songs may not be used in the liturgy. 3. A wedding liturgy is not a “wedding with concert attached.” The music selection and the musicians must be servants of the liturgy, not the other way around. 4. In Roman Catholic Liturgy, we worship together, here and now. Therefore, the Church does not allow recorded music or accompaniment/karaoke tracks in the Liturgy. OUTLINE OF THE NUPTIAL MASS: *Denotes a point in the liturgy where music may be used +Denotes musical setting of the Ordinary parts of the Mass. Should all be chosen from the same setting. *Prelude: About 20 minutes of music; can be instrumental and/or vocal. *Seating of the Mother(s): Music to accompany the mothers as they are seated. May be either an instrumental or vocal selection. INTRODUCTORY RITES *Procession(s): Plural if music changes for the bride. Greeting *Gloria Should be a song of the entire Assembly if possible. At OLMC, possibilities include: Simple Latin chant (Journeysongs #169) click here to listen Roman Missal chant in English (Journeysongs #146) click here to listen (videos 5, 11, 12, 14, & 16) Mass of Wisdom (Janco) click here to listen Mass of Renewal (Stephan): (Journeysongs #176) click here to listen Opening Prayer LITURGY OF THE WORD 1st Reading May be read by a Catholic lay reader. -

“The Great Thanksgiving,” Which Remind Us of What God Did for Us in Jesus

The words we say in preparation are often called “The Great Thanksgiving,” which remind us of what God did for us in Jesus. It begins with a call and response called the “Sursum Corda” from the Latin words for “Lift up your hearts.” It is an ancient part of the liturgy since the very early centuries of the Church, and a remnant of an early Jewish call to worship. These words remind us that when we observe communion, we are to be thankful and joyful. The Lord be with you. And also with you. Lift up your hearts. We lift them up to the Lord. Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. It is right to give our thanks and praise. The next section is spoken by the clergy and is called “The Proper Preface.” It has optional words that connect to the particular day or season of the church year. We will notice that by the time this communion liturgy is over, it will have covered all three parts of the Trinity. This first section focuses on God the Father: It is right, and a good and joyful thing, always and everywhere to give thanks to you, Father Almighty, creator of heaven and earth. The congregation then recites “The Sanctus,” from the Latin word for “Holy.” It comes from two Scripture texts: 1) Isaiah’s vision of heaven in Isaiah 6:3: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory,” and 2) Matthew 21:9, in which Jesus enters Jerusalem and the people shout, “Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest heaven!” These words remind us that through communion, we enter a holy experience with Jesus.