WELCOME to YINDEE Memories of Making Wake in Fright Somebody

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wake in Fright

Ryde Library Service Community Book Club Collection Wake in Fright By Kenneth Cook First published in 1961 Genre & subject Horror Australian fiction Synopsis Wake in Fright tells the tale of John Grant's journey into an alcoholic, sexual and spiritual nightmare. It is the original and greatest outback horror story. Bundanyabba and its citizens will haunt you forever. Author biography Kenneth Cook was born in Sydney. Wake in Fright, which drew on his time as a journalist in Broken Hill, was first published in 1961 when Cook was thirty-two. It was published in England and America, translated into several languages, and a prescribed text in schools. Cook wrote twenty-one books in a variety of genres, and was well known in film circles as a scriptwriter and independent film-maker. He died in 1987 at the age of fifty-seven. Discussion starters • How did you experience the book? Were you engaged immediately, or did it take you a while to "get into it"? How did you feel reading it? • What did you think of John Grant?—personality traits, motivations, inner qualities. • Are his actions justified? • How has the past shaped him? • How does Grant change by the end of the book? Does he learn something about himself and how the world works? • What main ideas—themes—does the Cook explore? Does he use symbols to reinforce the main ideas? • What passages strike you as insightful, even profound? Perhaps a bit of dialog that's funny or poignant or that encapsulates a character? Maybe there's a particular comment that states the book's thematic concerns? • Is the ending satisfying? If so, why? If not, why not...and how would you change it? Page 1 of 2 Ryde Library Service Community Book Club Collection If you liked this book, you may also like… The watch tower by Elizabeth Harrower Theft by Peter Carey If you are looking for something new to read try NoveList! It is a free database to help you find that perfect book. -

Amongst Friends: the Australian Cult Film Experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2013 Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Middlemost, Renee Michelle, Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication, University of Wollongong, 2013. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4063 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Amongst Friends: The Australian Cult Film Experience A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY From UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG By Renee Michelle MIDDLEMOST (B Arts (Honours) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications Faculty of Law, Humanities and The Arts 2013 1 Certification I, Renee Michelle Middlemost, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Renee Middlemost December 2013 2 Table of Contents Title 1 Certification 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Special Names or Abbreviations 6 Abstract 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction -

Volume 8, Number 1

POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State -

Straya Mate: Probing an Australian Masculinity Through Landscape Narrative, Visual Art and Dystopian Cinema

‘STRAYA MATE: PROBING AN AUSTRALIAN MASCULINITY THROUGH LANDSCAPE NARRATIVE, VISUAL ART AND DYSTOPIAN CINEMA ASHLEY DAVID KERR This paper explores the prevalence of landscape narratives in art and cinema containing post-apocalyptic futures, bushranger mythology and vigilantism, with a focus on the type of masculinity reflected within these contexts. I will introduce the kind of masculinity that is attributed to Australian men as part of a national myth of character, and will examine various dystopic film narratives, such asMad Max 2 (1981) and its recent counterpart The Rover(2014). In other words, I am drawn to narratives that feature a decline of civilisation, are set in an expansive Australian landscape, and often contain troubled male protagonists. I wish to demonstrate that this landscape, and its history of violence, hostility and suffering, feeds into post-colonial representations of reworked historical narratives and characters. Here, I link the American frontier to Australian representations of the fringe of white settlement via film theorist David Melbye’s theory on landscape allegory. I also present creative works of my own that were produced in relation to these ideas, and use them to explore male characters not only as a facet of Australian cultural identity, but also in relation to wider concerns of masculinity and nature. I conclude with a discussion about Australian artists of my generation who are also tackling the issue of ‘Aussie’ masculinity. AUSSIE BLOKES Masculinity in ‘White Australia’ has been shaped by the pioneering spirit of the colony, and its dominant formation remains a complex construction of Anglo-Saxon settler experience. It can be read as a vestige, if you will, of the hardships of the colony, such as the brutality of conditions faced by convicts, the competition of the Gold Rush and land prospecting, and the physical struggle of convicts and free settlers alike with the harsh Australian environment. -

WAY out WEST by Ian Muldoon* ______

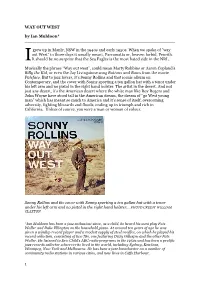

WAY OUT WEST by Ian Muldoon* __________________________________________________________ grew up in Manly, NSW in the 1940s and early 1950s. When we spoke of "way out West” in those days it usually meant, Parramatta or, heaven forbid, Penrith. I It should be no surprise that the Sea Eagles is the most hated side in the NRL. Musically the phrase “Way out west”, could mean Marty Robbins or Aaron Copland’s Billy the Kid, or even the Jay Livingstone song Buttons and Bows from the movie Paleface. But to jazz lovers, it’s Sonny Rollins and that iconic album on Contemporary, and the cover with Sonny sporting a ten gallon hat with a tenor under his left arm and no pistol in the right hand holster. The artist in the desert. And not just any desert, it’s the American desert where the white man like Roy Rogers and John Wayne have stood tall in the American dream, the dream of “go West young man” which has meant so much to America and it’s sense of itself, overcoming adversity, fighting blizzards and floods, ending up in triumph and rich in California. Unless of course, you were a man or woman of colour. Sonny Rollins and the cover with Sonny sporting a ten gallon hat with a tenor under his left arm and no pistol in the right hand holster... PHOTO CREDIT WILLIAM CLAXTON _________________________________________________________ *Ian Muldoon has been a jazz enthusiast since, as a child, he heard his aunt play Fats Waller and Duke Ellington on the household piano. At around ten years of age he was given a windup record player and a modest supply of steel needles, on which he played his record collection, consisting of two 78s, one featuring Dizzy Gillespie and the other Fats Waller. -

The Branagh Film

SYDNEY STUDIES IN ENGLISH DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY Volume 36, 2010 PENNY GAY: ‗A Romantic Musical Comedy‘ for the Fin-de-Siecle: Branagh‘s Love’s Labour’s Lost 1 BEN JUERS: Slapstick and Self-Reflexivity in George Herriman‘s Krazy Kat 22 JULIAN MURPHET: Realism in The Wire 52 LUKE HARLEY: An Apollonian Scream: Nathaniel Mackey‘s Rewriting of the Coltrane Poem in ‗Ohnedaruth‘s Day Begun‘ 77 REBECCA JOHINKE: Uncanny Carnage in Peter Weir‘s The Cars That Ate Paris 108 77 PETER KIRKPATRICK: Life and Love and ‗Lasca‘ 127 MARK BYRON: Digital Scholarly Editions of Modernist Texts: Navigating the Text in Samuel Beckett‘s Watt Manuscripts 150 DAVID KELLY: Narrative and Narration in John Ford‘s The Searchers 170 Editor: David Kelly Sydney Studies in English is published annually, concentrating on criticism and scholarship in English literature, drama and cinema. It aims to provide a forum for critical, scholarly and applied theoretical analysis of text, and seeks to balance the complexities of the discipline with the need to remain accessible to the wide audience of teachers and students of English both inside and outside the university. Submissions of articles should be made online at http://escholarship.library.usyd.edu.au/journals/index.php/SSE/about/sub missions#onlineSubmissions Each article will be read by at least two referees. Sydney Studies in English is published in association with the Department of English, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. Visit the Department‘s homepage at: http://sydney.edu.au/arts/english/ ISSN: 0156-5419 (print) ISSN: 1835-8071 (online) Sydney Studies in English 36 Special Edition: The Texts of Contemporary English Studies This volume of Sydney Studies in English is concerned with the changing nature of the text for the study of English. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Guide to Film Movements

This was originally published by Empire ( here is their Best of 2020 list) but no longer available. A Guide to Film Movements . FRENCH IMPRESSIONISM (1918-1930) Key filmmakers: Abel Gance, Louis Delluc, Germaine Dulac, Marcel L'Herbier, Jean Epstein What is it? The French Impressionist filmmakers took their name from their painterly compatriots and applied it to a 1920s boom in silent film that jolted cinema in thrilling new directions. The devastation of World War I parlayed into films that delved into the darker corners of the human psyche and had a good rummage about while they were there. New techniques in non-linear editing, point-of-view storytelling and camera work abounded. Abel Gance’s Napoleon introduced the widescreen camera and even stuck a camera operator on rollerskates to get a shot, while Marcel L'Herbier experimented with stark new lighting styles. Directors like Gance, Germaine Dulac and Jean Epstein found valuable support from Pathé Fréres and Leon Gaumont, France’s main production houses, in a reaction to the stifling influx of American films. As Empire writer and cineguru David Parkinson points out in 100 Ideas That Changed Film, the group’s figurehead, Louis Delluc, was instrumental in the still-new art form being embraced as something apart, artistically and geographically. “French cinema must be cinema,” he stressed. “French cinema must be French.” And being French, it wasn’t afraid to get a little sexy if the circumstances demanded. Germaine Dulac’s The Seashell And The Clergyman, an early step towards surrealism, gets into the head of a lascivious priest gingering after a general’s wife in a way usually frowned on in religious circles. -

Country Towns in Australian Films: Trap and Comfort Zone

Country Towns in Australian Films: Trap or Comfort Zone? It was watching Strange Bedfellows (Dean Murphy, 2004) last year, with its patronizing view of country-town life, that set me to wonder about how Australian cinema has viewed these buffers between the metropolis and the bush, about what kinds of narratives it has spun around and inside them. BY BRIAN McFARLANE everal films of the last couple of years foregrounded, for me at least, the perception that the country town is neither one thing nor the other, and that it has rarely been subject to the scrutiny afforded the demographic extremes. What follows is more in the nature of reflection and speculation than orderly survey. To turn to Hollywood, glitzy capital of the filmmaking world, one finds paradox- ically that small-town Americana was practically a narrative staple, that there was almost a genre of films which took seriously what such towns had to offer. 46 • Metro Magazine 146/147 Metro Magazine 146 • 47 Genre, though, is perhaps not the best elty; and Cy Endfield’sImpulse (1954) re- word, as it suggests more similarity than moves its hero from the quotidian predict- these films are apt to exhibit. Think of ability of his solicitor’s office to the temp- Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1947) tations of the city and a dangerous wom- which so resonantly explores George Bai- an; while films such as Jack Clayton’s ley’s feeling of entrapment in Bedford Falls Room at the Top (1959) and Ken Loach’s and, then, his gratitude for the support it Kes (1969) relocate class, family and oth- offers him at the lowest point of his life. -

AFI PREVIEW Is Published by the Hip Hop Soundtrack

AFI_Preview_Issue58 (FNL1)at.indd 1 8/31/12 11:59 AM Contents Latin american FiLm FestivaL September 20–October 10 2012 AFI Latin American Film Festival ........2 DC Labor FilmFest .....................................9 Now in its 23rd year, the AFI Latin American Film Festival OPENING NIGHT showcases the best filmmaking from Latin America and, with Noir City DC: The 2012 the inclusion of films from Spain and Portugal, celebrates Film Noir Festival ...................................10 Ibero-American cultural connections. This year’s selection Halloween on Screen ............................. of over 50 films makes it the biggest festival yet, featuring 12 international festival favorites, award-winners, local box- Spooky Movie International office hits and debut works by promising new talents. Media Indomina of Courtesy Horror Film Festival ................................13 Look for featured strands in this year’s lineup including: ALIEN: Retrospective ...............................13 Music Movies Family Fun Late-Night Latin Special Engagements .............................14 Calendar ...............................................15 All films are in Spanish with English subtitles Silent Classics with Alloy Orchestra, unless otherwise noted. Opera & Ballet in Cinema and Festival A NOTE TO AUDIENCES: of New Spanish Cinema .........................16 Because films in the AFI Latin American Film Festival have not been evaluated by the MPAA rating system in the US, AFI has made its LOOK FOR THE best effort to inform audiences about any content that could lead To become a Member of AFI visit to a restricted rating if released here. The following is a guide: AFI.com/Silver/JoinNow FiLLY BrOWn sexuality violence drug use language TICKETS In person: filmmakers Youssef Delara and Michael D. Olmos • $11.50 General Admission All showtimes are correct at press time. -

The Imagined Desert 1

Coolabah, No.11, 2013, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians, Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona The Imagined Desert 1 Tom Drahos Copyright©2013 Tom Drahos. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged. Abstract: The following analysis of the Australian Outback as an imagined space is informed by theories describing a separation from the objective physical world and the mapping of its representative double through language, and draws upon a reading of the function of landscape in three fictions; Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1899), Greg Mclean’s 2005 horror film Wolf Creek and Ted Kotcheff’s 1971 cinematic adaptation of Kenneth Cook’s novel Wake in Fright2. I would like to consider the Outback as a culturally produced text, and compare the function of this landscape as a cultural ‘reality’ to the function of landscape in literary and cinematic fiction. The Outback is hardly a place, but a narrative. An imagined realm, it exists against a backdrop of cultural memories and horror stories; ironically it is itself the backdrop to these accounts. In this sense, the Outback is at once a textual space and a text, a site of myth making and the product of myth. Ross Gibson defines landscape as a place where nature and culture combine in history: ‘As soon as you experience thoughts, emotions or actions in a tract of land, you find you’re in a landscape’3. Edward W. -

The Killing of Angel Street

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Goldsmith, Ben (2012) The Killing of Angel Street. Metro Magazine, 174, pp. 70-81. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/55476/ c Copyright 2012 Australian Teachers of Media This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.metromagazine.com.au/ magazine/ index.html The Killing of Angel Street Ben Goldsmith The Killing of Angel Street (Donald Crombie, 1981) opens with a classic black-and-white shot of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. This, as we will soon discover, is the view from the fictional street of the title.