The Imagined Desert 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Production Notes Greg Haddrick, Greg Mclean Nick Forward, Rob Gibson, Jo Rooney, Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS

A Stan Original Series presents A Screentime, a Banijay Group company, production, in association with Emu Creek Pictures financed with the assistance of Screen Australia and the South Australian Film Corporation Based on the feature films WOLF CREEK written, directed and produced by Greg McLean Adapted for television by Peter Gawler, Greg McLean & Felicity Packard Production Notes Greg Haddrick, Greg McLean Nick Forward, Rob Gibson, Jo Rooney, Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Elisa Argenzio PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Felicity Packard SERIES WRITERS Tony Tilse & Greg McLean SERIES DIRECTORS As at 2.3.16 As at 2.3.16 TABLE OF CONTENTS Key Cast Page 3 Production Information Page 4 About Stan. and About Screentime Page 5 Series Synopsis Page 6 Episode Synopses Pages 7 to 12 Select Cast Biographies & Character Descriptors Pages 15 to 33 Key Crew Biographies Pages 36 to 44 Select Production Interviews Pages 46 to 62 2 KEY CAST JOHN JARRATT Mick Taylor LUCY FRY Eve Thorogood DUSTIN CLARE Detective Sergeant Sullivan Hill and in Alphabetical Order EDDIE BAROO Ginger Jurkewitz CAMERON CAULFIELD Ross Thorogood RICHARD CAWTHORNE Kane Jurkewitz JACK CHARLES Uncle Paddy LIANA CORNELL Ann-Marie RHONDDA FINDELTON Deborah ALICIA GARDINER Senior Constable Janine Howard RACHEL HOUSE Ruth FLETCHER HUMPHRYS Jesus (Ben Mitchell) MATT LEVETT Kevin DEBORAH MAILMAN Bernadette JAKE RYAN Johnny the Convict MAYA STANGE Ingrid Thorogood GARY SWEET Jason MIRANDA TAPSELL Constable Fatima Johnson ROBERT TAYLOR Roland Thorogood JESSICA TOVEY Kirsty Hill 3 PRODUCTION INFORMATION Title: WOLF CREEK Format: 6 X 1 Hour Drama Series Logline: Mick Taylor returns to wreak havoc in WOLF CREEK. -

The 66Th Sydney Film Festival Begins 05/06/2019

MEDIA RELEASE: 9:00pm WEDNESDAY 5 JUNE 2019 THE 66TH SYDNEY FILM FESTIVAL BEGINS The 66th Sydney Film Festival (5 – 16 June) opened tonight at the State Theatre with the World Premiere of Australian drama/comedy Palm Beach. Festival Director Nashen Moodley was pleased to open his eighth Festival to a packed auditorium including Palm Beach director Rachel Ward and producers Bryan Brown and Deborah Balderstone, alongside cast members Aaron Jefferies, Jacqueline McKenzie, Heather Mitchell, Sam Neill, Greta Scacchi, Claire van der Boom, and Frances Berry. Following an announcement of increased NSW Government funding by the Premier Gladys Berejiklian, Minister for the Arts Don Harwin commented, “Launching with Palm Beach is the perfect salute to great Australian filmmaking in a year that will showcase a bumper list of contemporary Australian stories, including 24 World Premieres.” “As one of the world’s longest-running film festivals, I’m delighted to build on our support for the Festival and Travelling Film Festival over the next four years with increased funding of over $5 million, and look forward to the exciting plans in store,” he said. Sydney Film Festival Board Chair, Deanne Weir said, “The Sydney Film Festival Board are thrilled and grateful to the New South Wales Government for this renewed and increased support. The government's commitment recognizes the ongoing success of the Festival as one of the great film festivals of the world; and the leading role New South Wales plays in the Australian film industry.” Lord Mayor of Sydney, Clover Moore also spoke, declaring the Festival open. “The Sydney Film Festival’s growth and evolution has reflected that of Sydney itself – giving us a window to other worlds, to enjoy new and different ways of thinking and being, and to reach a greater understanding of ourselves and our own place in the world.” “The City of Sydney is proud to continue our support for the Sydney Film Festival. -

Wake in Fright

Ryde Library Service Community Book Club Collection Wake in Fright By Kenneth Cook First published in 1961 Genre & subject Horror Australian fiction Synopsis Wake in Fright tells the tale of John Grant's journey into an alcoholic, sexual and spiritual nightmare. It is the original and greatest outback horror story. Bundanyabba and its citizens will haunt you forever. Author biography Kenneth Cook was born in Sydney. Wake in Fright, which drew on his time as a journalist in Broken Hill, was first published in 1961 when Cook was thirty-two. It was published in England and America, translated into several languages, and a prescribed text in schools. Cook wrote twenty-one books in a variety of genres, and was well known in film circles as a scriptwriter and independent film-maker. He died in 1987 at the age of fifty-seven. Discussion starters • How did you experience the book? Were you engaged immediately, or did it take you a while to "get into it"? How did you feel reading it? • What did you think of John Grant?—personality traits, motivations, inner qualities. • Are his actions justified? • How has the past shaped him? • How does Grant change by the end of the book? Does he learn something about himself and how the world works? • What main ideas—themes—does the Cook explore? Does he use symbols to reinforce the main ideas? • What passages strike you as insightful, even profound? Perhaps a bit of dialog that's funny or poignant or that encapsulates a character? Maybe there's a particular comment that states the book's thematic concerns? • Is the ending satisfying? If so, why? If not, why not...and how would you change it? Page 1 of 2 Ryde Library Service Community Book Club Collection If you liked this book, you may also like… The watch tower by Elizabeth Harrower Theft by Peter Carey If you are looking for something new to read try NoveList! It is a free database to help you find that perfect book. -

Amongst Friends: the Australian Cult Film Experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2013 Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Middlemost, Renee Michelle, Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication, University of Wollongong, 2013. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4063 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Amongst Friends: The Australian Cult Film Experience A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY From UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG By Renee Michelle MIDDLEMOST (B Arts (Honours) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications Faculty of Law, Humanities and The Arts 2013 1 Certification I, Renee Michelle Middlemost, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Renee Middlemost December 2013 2 Table of Contents Title 1 Certification 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Special Names or Abbreviations 6 Abstract 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction -

Volume 8, Number 1

POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State -

John Forbes's Poetry of Metaphysical Etiquette

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Instruction for an Ideal Australian: John Forbes’s Poetry of Metaphysical Etiquette DUNCAN HOSE University of Melbourne I want to approach the work of John Forbes as being exemplary of a process which combines mythography and mythopoesis, or the constant re-reading and re-writing of the myths one lives by. The articles of concern here are both the personal mythemes that are aggregated by the individual subject in the business of identity construction, and the mass of national mythic capital that continually circulates, wanting to displace difference and coax the subject into a kind of sentimental symbolic citizenship. Forbes took very seriously the poststructuralist revolutions in epistemology and ontology, and his poetry is characterized by an intense scepticism about the capacity of language to represent the world properly, and an allied cynicism toward the products of self- mythologising, preferring the hedonism, and in a strange way the anxiety, of the de- centred subject licensed by postmodernism. I want to read here a few of Forbes’s poems as a possible charter for a new metaphysics, and perhaps a new kind of old-fashioned etiquette. As the title of this paper suggests, there is often some haranguing quality in this poet’s work: one is always being upbraided, or at least addressed; it is immediately a social poetry that does not function as a model of Romantic self-calibration, or subscribe to the self as an economic or philosophical unit, except sarcastically. -

Il DOMANI CHE VERRÀ

Presenta con CAITLIN STASEY, RACHEL HURD-WOOD, LINCOLN LEWIS, DENIZ AKDENIZ, PHOEBE TONKIN, CHRISTOPHER PANG, ASHLEIGH CUMMINGS, ANDREW RYAN E COLIN FRIELS Sceneggiatura e Regia STUART BEATTIE Tratto dal bestseller di JOHN MARSDEN Edito in Italia da FAZI EDITORE Durata 100’ DAL 4 NOVEMBRE AL CINEMA I materiali sono scaricabili dall’ area stampa di www.eaglepictures.com Ufficio Stampa Eagle Pictures Marianna Giorgi [email protected] THE TOMORROW SERIES: Il DOMANI CHE VERRÀ IL CAST Ellie Linton CAITLIN STASEY Corrie McKenzie RACHEL HURD-WOOD Kevin Holmes LINCOLN LEWIS Homer Yannos DENIZ AKDENIZ Fiona Maxwell PHOEBE TONKIN Lee Takkam CHRISTOPHER PANG Robyn Mathers ASHLEIGH CUMMINGS Chris Lang ANDREW RYAN Dottor Clement COLIN FRIELS I REALIZZATORI Scritto e diretto da STUART BEATTIE Tratto dal romanzo di JOHN MARSDEN Prodotto da ANDREW MASON MICHAEL BOUGHEN Produttori Esecutivi: CHRISTOPHER MAPP MATTHEW STREET DAVID WHEALY PETER GRAVES Line Producer: ANNE BRUNING Direttore della Fotografia: BEN NOTT ACS Montatore: MARCUS D’ARCY Musiche Originali di JOHNNY KLIMEK e REINHOLD HEIL Scenografo: ROBERT WEBB Supervisore alla scenografia: MICHELLE McGAHEY Supervisore agli Effetti Visivi: CHRIS GODFREY Costumi: TERRY RYAN Casting: ANOUSHA ZARKESH THE TOMORROW SERIES: Il DOMANI CHE VERRÀ SINOSSI The Tomorrow Series: Il domani che Verrà è la storia di otto amici della scuola superiore di un paese rurale sulla costa, le cui vite sono improvvisamente e violentemente stravolte da una invasione che nessuno aveva previsto. Separati dalle loro famiglie e dagli amici, questi straordinari ragazzi devono imparare a sfuggire ad ostili forze militari, a combattere e a sopravvivere. SINOSSI LUNGA The Tomorrow Series: Il domani che Verrà è la storia di otto amici della scuola superiore di un paese rurale sulla costa, le cui vite sono improvvisamente e violentemente travolte da una invasione che nessuno aveva visto arrivare. -

Australian Dream Music

Musical Director Colin Timms The Band David Baker Stefan Greder Neil Healey Songs Produced and arranged by Colin Timms Lyrics by Chris McKimmie Music by David Baker & Stefan Greder Performed by Chris McKimmie Stefan Greder David Baker Neil Harvey "Twenty-Two Questions" "Australian Dream" sung by Noni Hazlehurst & Graeme Blundell "Lying Together" sung by Noni Hazlehurst "I Wanna Be A Typewriter" sung by Noni Hazlehurst & John Jarratt "Blind Date" "Too Much Fun" "I Don't Wear Underpants" sung by John Jarratt All other songs and incidental music composed by Colin Timms Music recorded at Suite 16, Brisbane "Caroline" written and sung by Lee & Thelma Morris Lyrics for the head and tail songs that run over credits: Head credits song: (with sounds of typewriter and rhythmic musical beat, lyrics are spoken): Graeme Blundell: A house, a boat, a TV. Noni Hazlehurst: One for the kids, one for me. Graeme Blundell: Don't read books, don't think, I'm healthy Together: Australian dream, Australian dream, Australian dream, Australian dream … (Voice singing scat of the "doodah" style) Noni Hazlehurst: Got a dish washer, huge debts, and two cars Graeme Blundell: One for the wife and one for me … A huge house, a wife, a double garage ... (Over shots of missionaries cycling down a suburban street) Together: Australian dream, Australian dream, Australian dream, Australian dream … (Voice singing scat of the "doodah" style) Noni Hazlehurst: Is that it? (after the camera tracks past John Jarratt smoking, while sitting in a car, music fades out over a hen's party -

Straya Mate: Probing an Australian Masculinity Through Landscape Narrative, Visual Art and Dystopian Cinema

‘STRAYA MATE: PROBING AN AUSTRALIAN MASCULINITY THROUGH LANDSCAPE NARRATIVE, VISUAL ART AND DYSTOPIAN CINEMA ASHLEY DAVID KERR This paper explores the prevalence of landscape narratives in art and cinema containing post-apocalyptic futures, bushranger mythology and vigilantism, with a focus on the type of masculinity reflected within these contexts. I will introduce the kind of masculinity that is attributed to Australian men as part of a national myth of character, and will examine various dystopic film narratives, such asMad Max 2 (1981) and its recent counterpart The Rover(2014). In other words, I am drawn to narratives that feature a decline of civilisation, are set in an expansive Australian landscape, and often contain troubled male protagonists. I wish to demonstrate that this landscape, and its history of violence, hostility and suffering, feeds into post-colonial representations of reworked historical narratives and characters. Here, I link the American frontier to Australian representations of the fringe of white settlement via film theorist David Melbye’s theory on landscape allegory. I also present creative works of my own that were produced in relation to these ideas, and use them to explore male characters not only as a facet of Australian cultural identity, but also in relation to wider concerns of masculinity and nature. I conclude with a discussion about Australian artists of my generation who are also tackling the issue of ‘Aussie’ masculinity. AUSSIE BLOKES Masculinity in ‘White Australia’ has been shaped by the pioneering spirit of the colony, and its dominant formation remains a complex construction of Anglo-Saxon settler experience. It can be read as a vestige, if you will, of the hardships of the colony, such as the brutality of conditions faced by convicts, the competition of the Gold Rush and land prospecting, and the physical struggle of convicts and free settlers alike with the harsh Australian environment. -

Theatre Australia Historical & Cultural Collections

University of Wollongong Research Online Theatre Australia Historical & Cultural Collections 11-1977 Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977 Robert Page Editor Lucy Wagner Editor Bruce Knappett Associate Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theatreaustralia Recommended Citation Page, Robert; Wagner, Lucy; and Knappett, Bruce, (1977), Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977, Theatre Publications Ltd., New Lambton Heights, 66p. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theatreaustralia/14 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977 Description Contents: Departments 2 Comments 4 Quotes and Queries 5 Letters 6 Whispers, Rumours and Facts 62 Guide, Theatre, Opera, Dance 3 Spotlight Peter Hemmings Features 7 Tracks and Ways - Robin Ramsay talks to Theatre Australia 16 The Edgleys: A Theatre Family Raymond Stanley 22 Sydney’s Theatre - the Theatre Royal Ross Thorne 14 The Role of the Critic - Frances Kelly and Robert Page Playscript 41 Jack by Jim O’Neill Studyguide 10 Louis Esson Jess Wilkins Regional Theatre 12 The Armidale Experience Ray Omodei and Diana Sharpe Opera 53 Sydney Comes Second best David Gyger 18 The Two Macbeths David Gyger Ballet 58 Two Conservative Managements William Shoubridge Theatre Reviews 25 Western Australia King Edward the Second Long Day’s Journey into Night Of Mice and Men 28 South Australia Annie Get Your Gun HMS Pinafore City Sugar 31 A.C.T. -

EDITORIAL by the Time You Read This Our Conference Will Be Over, and the Autumn Session of Meetings Will Be Well Under Way

EDITORIAL By the time you read this our Conference will be over, and the Autumn session of meetings will be well under way. The Society continues to grow, and the various local groups are all flourishing. Various projects such as Census Indexing and M.I. Recording are proceeding, but more volunteers to assist in the work are always welcome. As mentioned in the last issue of the Journal, our Treasurer John Scott is retiring from the job after a stint of eight years, and in recognition of his long and devoted service he is to be made an Honorary Life Member of the Society. We were worried about finding a successor to take over from John, but fortunately a volunteer, Miss Cindy Winters, has come forward, and we wish her well in her new position. Liz Lyall, the prime mover in the organisation of our Annual Conferences, is also retiring, and we take this opportunity of thanking her for all the work she has put in to make our Conferences so successful. I trust that members will continue to submit articles and other items of interest for publication in the Journal. It is time we had a Durham parish in the `Know Your Parish' series: there have only been six (Medomsley, Heworth, Chester-le-Street, Washington, Tanfield and Hetton-le-Hole) since the series started more than eight years ago! So how about it, you Durham folk? NEWS IN BRIEF We Should've Listened to Grandma Dr Noeline Kyle, of the Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong, P.O. Box 1144, WOLLONGONG 2500, AUSTRALIA, is writing a book to be entitled We Should've Listened to Grandma: Tracing Women Ancestors. -

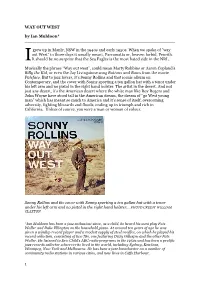

WAY out WEST by Ian Muldoon* ______

WAY OUT WEST by Ian Muldoon* __________________________________________________________ grew up in Manly, NSW in the 1940s and early 1950s. When we spoke of "way out West” in those days it usually meant, Parramatta or, heaven forbid, Penrith. I It should be no surprise that the Sea Eagles is the most hated side in the NRL. Musically the phrase “Way out west”, could mean Marty Robbins or Aaron Copland’s Billy the Kid, or even the Jay Livingstone song Buttons and Bows from the movie Paleface. But to jazz lovers, it’s Sonny Rollins and that iconic album on Contemporary, and the cover with Sonny sporting a ten gallon hat with a tenor under his left arm and no pistol in the right hand holster. The artist in the desert. And not just any desert, it’s the American desert where the white man like Roy Rogers and John Wayne have stood tall in the American dream, the dream of “go West young man” which has meant so much to America and it’s sense of itself, overcoming adversity, fighting blizzards and floods, ending up in triumph and rich in California. Unless of course, you were a man or woman of colour. Sonny Rollins and the cover with Sonny sporting a ten gallon hat with a tenor under his left arm and no pistol in the right hand holster... PHOTO CREDIT WILLIAM CLAXTON _________________________________________________________ *Ian Muldoon has been a jazz enthusiast since, as a child, he heard his aunt play Fats Waller and Duke Ellington on the household piano. At around ten years of age he was given a windup record player and a modest supply of steel needles, on which he played his record collection, consisting of two 78s, one featuring Dizzy Gillespie and the other Fats Waller.