RACHMANINOV Piano Concerto No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Musical Society Oslo Philharmonic

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OSLO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA MARISS JANSONS Music Director and Conductor FRANK PETER ZIMMERMANN, Violinist Sunday Evening, November 17, 1991, at 8:00 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan PROGRAM Concerto in E minor for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 64 . Mendelssohn Allegro molto appassionata Andante Allegretto non troppo, allegro molto vivace Frank Peter Zimmermann, Violinist INTERMISSION Symphony No. 7 in C major, Op. 60 ("Leningrad") ..... Shostakovich Allegretto Moderate Adagio, moderate risoluto Allegro non troppo CCC Norsk Hydro is proud to be the exclusive worldwide sponsor IfiBUt of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra for the period 1990-93. The Oslo Philharmonic and Frank Peter Zimmermann are represented by Columbia Artists Management Inc., New York City. The Philharmonic records for EMl/Angel, Chandos, and Polygram. The box office in the outer lobby is open during intermission for tickets to upcoming Musical Society concerts. Twelfth Concert of the 113th Season 113th Annual Choral Union Series Program Notes Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 root tone G on its lowest note, the flute and FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809-1847) clarinets in pairs are entrusted with the gentle melody. On the opening G string, the solo uring his short life of 38 years, violin becomes the fundament of this delicate Mendelssohn dominated the passage. The two themes are worked out until musical world of Germany and their development reaches the cadenza, exercised the same influence in which Mendelssohn wrote out in full. The England for more than a gener cadenza, in turn, serves as a transition to the ationD after his death. The reason for this may reprise. -

Yoon-Hee Kim Plays

CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer RPO YELLOW Catalogue No. SP-046 BLACK Job Title Yoon-Hee Kim Page Nos. ‘The profundity of her emotions impresses much more than her technical perfection. Her performance connects virtuosity, energy and passion’ – Rheinische Post, Germany ‘She demonstrates an extraordinary musicality, a strong expression and an absolutely perfect technique’ – Kölner Klassik YOON-HEE KIM PLAYS ‘A sensation … No-one can compete with her extraordinary musicality’ – Adresseavisen , Norway ‘Amazing performance’ – Austria Today KHACHATURIAN & TCHAIKOVSKY VIOLIN CONCERTOS YOON-HEE KIM VIOLIN . BARRY WORDSWORTH CONDUCTOR CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer RPO YELLOW Catalogue No. SP-046 BLACK Job Title Yoon-Hee Kim Page Nos. By the early 1940s Khachaturian was riding on the crest of a wave of popular success. ARAM KHACHATURIAN (1903 –1978) His Piano Concerto (1936) and Violin Concerto (1940) established him, alongside Violin Concerto in D minor (1940) Prokofiev and Shostakovich, as one of Russia’s most celebrated composers. His I. Allegro con fermezza stunning incidental music to Lermontov’s Masquerade appeared in 1941 and the II. Andante sostenuto following year his epic ballet score Gayeneh was written, which included the ever- III. Allegro vivace popular whirlwind ‘Sabre Dance’. ‘I wrote the music as though on a wave of happiness; my whole being was in a state of joy, for I was awaiting the birth of my son. And this feeling, this love of life, was PYOTR TCHAIKOVSKY (1840 –1893) transmitted to the music.’ So saying, Khachaturian set the seal on his gloriously inspired Violin Concerto in D Op.35 (1878) Violin Concerto, composed over two months during the idyllic summer of 1940. -

Shostakovich (1906-1975)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Born in St. Petersburg. He entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13 and studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. His graduation piece, the Symphony No. 1, gave him immediate fame and from there he went on to become the greatest composer during the Soviet Era of Russian history despite serious problems with the political and cultural authorities. He also concertized as a pianist and taught at the Moscow Conservatory. He was a prolific composer whose compositions covered almost all genres from operas, ballets and film scores to works for solo instruments and voice. Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10 (1923-5) Yuri Ahronovich/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Overture on Russian and Kirghiz Folk Themes) MELODIYA SM 02581-2/MELODIYA ANGEL SR-40192 (1972) (LP) Karel Ancerl/Czech Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 5) SUPRAPHON ANCERL EDITION SU 36992 (2005) (original LP release: SUPRAPHON SUAST 50576) (1964) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, Festive Overture, October, The Song of the Forest, 5 Fragments, Funeral-Triumphal Prelude, Novorossiisk Chimes: Excerpts and Chamber Symphony, Op. 110a) DECCA 4758748-2 (12 CDs) (2007) (original CD release: DECCA 425609-2) (1990) Rudolf Barshai/Cologne West German Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1994) ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 6324 (11 CDs) (2003) Rudolf Barshai/Vancouver Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. -

Culture and the Arts Bring Meaning to Our Lives

Culture and the Arts bring meaning to our lives. Culture and the Arts make us the human beings we are and give structure and sense to the society we create; they provide us with real values and fulfil our mental and emotional existence. In the most difficult days of the history of humanity, alongside the most dramatic events, the most devastating wars and epidemics, the Arts, and perhaps especially music, enhanced the spirit. Music became a symbol of resilience, heroism and ultimately our belief in ourselves, from Josef Haydn’s ‘Mass in Time of War’ to Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony. We are at war now and we musicians are desperate to join in in the battle to help society, help people to improve their mental health, fire their spirit and give comfort during this most isolated, most lonely time in our modern history. But we can’t. We are prevented from performing in live spaces, prevented from reaching the eyes and ears and hearts of our public, prevented from sharing with them our love, our passion, our belief. It is becoming more and more apparent that orchestras, opera companies and other musical institutions in the UK, a truly world-leading country in all forms of culture, are in grave danger of being lost forever, if urgent action is not taken. Many of us have had great support through the Job Retention Scheme, and we are really grateful to the Government for that. But we need also to look to the coming months, and even years, and discuss what the impact of this closure, and of contained social distancing remaining, means for the performing arts. -

Vasily PETRENKO Conductor

Vasily PETRENKO Conductor Vasily Petrenko was born in 1976 and started his music education at the St Petersburg Capella Boys Music School – the oldest music school in Russia. He then studied at the St Petersburg Conservatoire and has also participated in masterclasses with such major figures as Ilya Musin, Mariss Jansons, and Yuri Temirkanov. Following considerable success in a number of international conducting competitions including the Fourth Prokofiev Conducting Competition in St Petersburg (2003), First Prize in the Shostakovich Choral Conducting Competition in St Petersburg (1997) and First Prize in the Sixth Cadaques International Conducting Competition in Spain, he was appointed Chief Conductor of the St Petersburg State Academic Symphony Orchestra from 2004 to 2007. Petrenko is Chief Conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra (appointed in 2013/14), Chief Conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (a position he adopted in 2009 as a continuation of his period as Principal Conductor which commenced in 2006), Chief Conductor of the European Union Youth Orchestra (since 2015) and Principal Guest Conductor of the State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia (since 2016). Petrenko has also served as Principal Conductor of the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain from 2009-2013, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Mikhailovsky Theatre (formerly the Mussorgsky Memorial Theatre of the St Petersburg State Opera and Ballet) where he began his career as Resident Conductor from 1994 to 1997. Petrenko has worked with many of the world’s most prestigious orchestras including the London Symphony Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Philharmonia, Russian National Orchestra, Orchestre National de France, Czech Philharmonic, Finnish Radio Symphony, NHK Symphony Tokyo and Sydney Symphony. -

Download Booklet

557757 bk Bloch US 20/8/07 8:50 pm Page 5 Royal Scottish National Orchestra the Sydney Opera, has been shown over fifty times on U.S. television, and has been released on DVD. Serebrier regularly champions contemporary music, having commissioned the String Quartet No. 4 by Elliot Carter (for his Formed in 1891 as the Scottish Orchestra, and subsequently known as the Scottish National Orchestra before being Festival Miami), and conducted world première performances of music by Rorem, Schuman, Ives, Knudsen, Biser, granted the title Royal at its centenary celebrations in 1991, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra is one of Europe’s and many others. As a composer, Serebrier has won most important awards in the United States, including two leading ensembles. Distinguished conductors who have contributed to the success of the orchestra include Sir John Guggenheims (as the youngest in that Foundation’s history, at the age of nineteen), Rockefeller Foundation grants, Barbirolli, Karl Rankl, Hans Swarowsky, Walter Susskind, Sir Alexander Gibson, Bryden Thomson, Neeme Järvi, commissions from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Harvard Musical Association, the B.M.I. Award, now Conductor Laureate, and Walter Weller who is now Conductor Emeritus. Alexander Lazarev, who served as Koussevitzky Foundation Award, among others. Born in Uruguay of Russian and Polish parents, Serebrier has Ernest Principal Conductor from 1997 to 2005, was recently appointed Conductor Emeritus. Stéphane Denève was composed more than a hundred works. His First Symphony had its première under Leopold Stokowski (who gave appointed Music Director in 2005 and his first recording with the RSNO of Albert Roussel’s Symphony No. -

February 2017 Events

Events February 2017 Sightseeing Tours Highlights in February Historical city centre and Ljubljana castle Take a walk around the historical city centre, explore major Natour Alpe-Adria attractions and Ljubljana Castle. Daily at 11:00 Index From: in front the Town Hall (duration 2 hours) Language: Slovene, English Price: adults € 13, children € 6,5, with Ljubljana Tourist card free of charge. Walking tour of Plečnik’s Ljubljana Festivals 4 An exploration of the life and work of the greatest Slovene architect. Exhibitions 5 Wednesdays and Saturdays at 12:00 From: Tourist Information Centre – TIC (duration 3 hours) Language: Slovene, English Price: € 20 Music 8 Taste Ljubljana culinary tour Opera, theatre, dance 14 Taste of 5 different dishes and 5 selected drinks included. Wednesdays and Saturdays at 12:00 Miscellaneous 15 From: Tourist Information Centre - TIC (duration 3 hours) Language: Slovene, English Price: € 38 Sports 15 Ljubljana beer lover’s experience Taste of 8 different beers and 3 snacks included, visit to Brewery Museum. Mondays and Fridays at 18:00 From: Slovenian Tourist Information Centre – STIC (duration 3 hours) Cover photo: D. Wedam Language: Slovene, English Edited and published by: Ljubljana Price: € 35 Tourism, Krekov trg 10, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Town Hall tour T: +386 1 306 45 83, E: [email protected], Saturdays at 13:00 From: in front of the Town Hall (duration 1 hour) W: www.visitljubljana.com Language: Slovene, English Photography: Archives of Ljubljana Price: € 5 Tourism and individual event organisers Prepress: Prajs d.o.o. Printed by: Partner Graf d.o.o., Ljubljana, February 2017 1 - 4 Feb 9 Feb 25 Feb Ljubljana Tourism is not liable for any inaccurate information appearing in the Natour Alpe-Adria Royal Philharmonic Dragon Carnival Visit the Natour Alpe-Adria Dragon Carnival consists of calendar. -

Musicweb International August 2020 RETROSPECTIVE SUMMER 2020

RETROSPECTIVE SUMMER 2020 By Brian Wilson The decision to axe the ‘Second Thoughts and Short Reviews’ feature left me with a vast array of part- written reviews, left unfinished after a colleague had got their thoughts online first, with not enough hours in the day to recast a full review in each case. This is an attempt to catch up. Even if in almost every case I find myself largely in agreement with the original review, a brief reminder of something you may have missed, with a slightly different slant, may be useful – and, occasionally, I may be raising a dissenting voice. Index [with page numbers] Malcolm ARNOLD Concerto for Organ and Orchestra – see Arthur BUTTERWORTH Johann Sebastian BACH Concertos for Harpsichord and Strings – Volume 1_BIS [2] Johann Sebastian BACH, Georg Philipp TELEMANN, Carl Philipp Emanuel BACH The Father, the Son and the Godfather_BIS [2] Sir Arnold BAX Morning Song ‘Maytime in Sussex’ – see RUBBRA Amy BEACH Piano Quintet (with ELGAR Piano Quintet)_Hyperion [9] Sir Arthur BLISS Piano Concerto in B-flat – see RUBBRA Benjamin BRITTEN Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, etc._Alto_Regis [15, 16] Arthur BUTTERWORTH Symphony No.1 (with Ruth GIPPS Symphony No.2, Malcolm ARNOLD Concerto for Organ and Orchestra)_Musical Concepts [16] Paul CORFIELD GODFREY Beren and Lúthien: Epic Scenes from the Silmarillion - Part Two_Prima Facie [17] Sir Edward ELGAR Symphony No.2_Decca [7] - Sea Pictures; Falstaff_Decca [6] - Falstaff; Cockaigne_Sony [7] - Sea Pictures; Alassio_Sony [7] - Violin Sonata (with Ralph VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Violin Sonata; The Lark Ascending)_Chandos [9] - Piano Quintet – see Amy BEACH Gerald FINZI Concerto for Clarinet and Strings – see VAUGHAN WILLIAMS [10] Ruth GIPPS Symphony No.2 – see Arthur BUTTERWORTH Alan GRAY Magnificat and Nunc dimittis in f minor – see STANFORD Modest MUSSORGSKY Pictures from an Exhibition (orch. -

CHAN 10425X Booklet.Indd

Gerald Finzi Classics Violin and Cello Concertos Tasmin Little violin Raphael Wallfi sch cello City of London Sinfonia Richard Hickox Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra Vernon Handley CHAN 10425 X Gerald Finzi (1901–1956) Cello Concerto, Op. 40 39:10 in A minor • in a-Moll • en la mineur Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library 1 I Allegro moderato 15:53 2 II Andante quieto 13:34 3 III Rondo: Adagio – Allegro giocoso 9:44 Raphael Wallfi sch cello Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra Malcolm Stewart leader Vernon Handley Gerald Finzi 3 Finzi: Cello Concerto and Violin Concerto Finzi completed his Cello Concerto for the reaches out to a major sixth, so swinging the 4 Prelude, Op. 25 5:00 Cheltenham Festival of 1955. He had long harmony round in its second bar to a major for string orchestra had a cello concerto in mind, and some of it chord; with this reaching out, and the fi erce Adagio espressivo – Poco più mosso – Tempo primo already composed, when Sir John Barbirolli trills, scotch-snap rhythms, and up-thrusting asked him for a major work; so the fi rst shape, the theme sets up a restless energy. performance was given by Christopher The second subject is a gentler cantabile, but 5 Romance, Op. 11 7:52 Bunting and The Hallé Orchestra under the movement ends stormily, gathered into a for string orchestra Barbirolli on 19 July 1955. cadenza and then despatched with four great Andante espressivo – Più mosso – Tempo primo Those who know Finzi only from his more hammer-blows. lyrical songs, perhaps even from his Clarinet The slow movement opens in a mood of † Concerto as well, may be surprised at the shy rapture, the song-melody beautifully Concerto for Small Orchestra and Solo Violin 20:05 breadth and power of this work. -

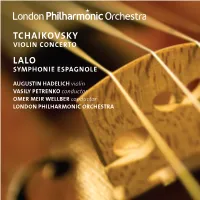

Tchaikovsky Lalo

TCHAIKOVSKY VIOLIN CONCERTO LALO SYMPHONIE ESPAGNOLE AUGUSTIN HADELICH violin VASILY PETRENKO conductor OMER MEIR WELLBER conductor LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA TCHAIKOVSKY VIOLIN coNCErto IN D major If there is a sense of awakening at the start Of the pieces Tchaikovsky and Kotek played of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, it is only through, one that particularly impressed the appropriate. Days before he started composing composer with its ‘freshness’ and ‘musical it in March 1878 he had been picking at a new beauty’ was Édouard Lalo’s new Symphonie piano sonata, with scant success: ‘Am I played espagnole for violin and orchestra. The out?’, he wrote in a letter. ‘I have to squeeze unassuming formal simplicity of Lalo’s out of myself weak and worthless ideas and approach also found its way into Tchaikovsky’s ponder every bar.’ He was writing from the Concerto, though this is not to say that it is house at Clarens near Lake Geneva, where he without craft. The first movement is a sonata was staying as part of his six-month escape form with an elegant introduction and two from Russia following the personal disaster clearly discernible big melodies amid some and mental breakdown provoked by his ill- more fleeting themes, all bound together by considered marriage the previous year. In that subtly glinting thematic connections. ‘Musical period of wandering he had completed both beauty’ is also present; like Mendelssohn in the Fourth Symphony and the opera Eugene his Violin Concerto, Tchaikovsky manages Onegin, but begun very little that was new in effortlessly to make natural partners of lyrical itself. -

Piano with Yonty Solomon

Dundee Symphony Orchestra is the performing name of Dundee Orchestral Society. The Society was founded in 1893 by a group of enthusiastic amateur performers, and has gone from strength to strength ever since. The only period in the Orchestra's history when it did not perform or rehearse was during the Second World War. The Orchestra is funded through private and charitable donations, subscriptions from members, and by grants from Making Music and the Scottish Arts Council. We would like to thank all those who provide financial assistance for the orchestra for their continuing support over the years. If you enjoy our concerts, we hope you will consider becoming a Friend of the Orchestra. This may be done by completing the form in the programme and returning it to the Friends Co-ordinator. To keep up to date with events visit the Orchestra website on www.dundeesymphonyorchestra.org The Society is affiliated to The National Federation of Music Societies 7-15 Rosebery Avenue, London EC1R 4SP Tel: 0870 872 3300 Fax: 0870 872 3400 Web site: www.makingmusic.org.uk 1 Robert Dick (Conductor) Robert Dick was born in Edinburgh in 1975. On leaving school, Robert entered the Royal College of Music in London studying violin with Grigori Zhislin and Madeleine Mitchell and piano with Yonty Solomon. He graduated with Honours in 1997 and also gained the Associateship Diploma of the Royal College of Music in Violin Performance. Robert has been conducting since he was 11. In 1993 he conducted the Royal Scottish National Orchestra at the invitation of its then Musical Director, Walter Weller, appearing with them again three years later and in 1995 Robert co-founded the reconstituted Orchestra of Old St Paul's in Edinburgh. -

Music Catalogue 2021

SUMMARY ELECTRONIC MUSIC p.04 CONTEMPORARY DANCE p.06 JAZZ p.12 OPERA p.14 CLASSICAL p.25 MUSIC DOCUMENTARY p.37 WORLD MUSIC p.40 4K CONCERTS p.42 3 4 The Sonar Festival ZSAMM ISAAC DELUSION LENGTH: LENGTH: 50’ 53’ DIRECTOR: DIRECTOR: SÉBASTIEN BERGÉ ERIC MICHAUD PRODUCER: PRODUCER: Les Films Jack Fébus Les Films Jack Fébus COPRODUCER: COPRODUCER: ARTE France M_Media COPYRIGHT: COPYRIGHT: 2018 2018 Live concert Live concert ARTIST NATIONALITY: ARTIST NATIONALITY: Slovenia, Austria France 27.10.22 07.09.22 Watch the video Watch the video 5 6 Contemporary dance MONUMENTS IN MOTION MONUMENTS IN MOTION SCREWS AND STONES I REMEMBER SAYING GOODBYE LENGTH: LENGTH: 11’ 11’ DIRECTOR: DIRECTOR: GAËTAN CHATAIGNER TOMMY PASCAL PRODUCER: PRODUCER: Les Films Jack Fébus Les Films Jack Fébus COPRODUCERS: COPRODUCERS: Centre des mouve- Centre des mouve- ments nationaux ments nationaux COPYRIGHT: COPYRIGHT: 2020 2019 LANGUAGE AVAILABLE: LANGUAGE AVAILABLE: Live concert Live concert 18.02.29 11.06.24 Watch the video Watch the video Choreography by Alexander Vantournhout Choreography by Christian and François Ben Aïm From the SCREWS performance At the Sainte Chapelle at La Conciergerie de Paris. Performers: Music : Nils Frahm Christien Ben Aïm Dancers : Josse De Broeck, Petra Steindl, Emmi François Ben Aïm Väisänen, Hendrik Van Maele, Alexander Vantournhout, Louis Gillard Felix Zech Piers Faccini (musician) 7 Contemporary dance MONUMENTS IN MOTION 3X10’ SCENA MADRE* LENGTH: LENGTH: 3x10’ 63’ DIRECTOR: DIRECTOR: YOANN GAREL, JULIA GAT, GAËTAN CHATAIGNER THOMAS