Shattered Humanity: the Brutality of Lynch Mob Formation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brent Ms Campney

BRENT M. S. CAMPNEY Professor | [email protected] EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy in American Studies, Emory University, 2007 Master of Arts in American Studies, University of Kansas, 2001 Bachelor of Arts in American Culture, University of Michigan, 1998 ACADEMIC POSITIONS Professor, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Department of History, 2019-Present Associate Professor, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Department of History, 2015-2019 Associate Professor, University of Texas-Pan American, Department of History and Philosophy, 2014- 2015 Assistant Professor, University of Texas-Pan American, Department of History and Philosophy, 2008- 2014 Instructor and Teaching Assistant, Emory University, Graduate Institute of Liberal Arts, 2003-2004 Instructor and Teaching Assistant, University of Kansas, Department of American Studies, 1999-2001 RESEARCH Monographs Hostile Heartland: Racism, Repression, and Resistance in the Midwest (University of Illinois Press, 2019) This is Not Dixie: Racist Violence in Kansas, 1861-1927 (University of Illinois Press, 2015; paperback 2018) Peer-Reviewed Articles & Book Chapters “‘Leave Him Now to the Great Judge’: The Short and Tragic Life of Allen Pinks; Free Black, Fugitive Slave, and Slave-Catcher,” Kansas History (Winter 2020): 210-223 “Anti-Japanese Sentiment, International Diplomacy, and the Texas Alien Land Law of 1921,” Journal of Southern History (November 2019): 841-878 “‘The Infamous Business of Kidnapping’: Slave-Catching in Kansas, 1858-1863,” Kansas History 42 (Summer 2019): 154-171 -

Publicity and the De-Legitimation of Lynching∗

\Judge Lynch" in the Court of Public Opinion: Publicity and the De-legitimation of Lynching∗ Michael Weaver Postdoctoral Fellow Department of Political Science University of British Columbiay [email protected] November 8, 2018 Abstract How does violence become publicly unacceptable? I address this question in the context of lynching in United States. Between 1880 and the 1930s, public discourse about lynching moved from open or tacit endorsement to widespread condemnation. I argue this occurred because of increasing publicity for lynchings. While locals justified nearby lynchings, publicity exposed lynching to distant, un-supportive audiences and allowed African Americans to safely articulate counter-narratives and condemnations. I test this argument using data on lynchings, rail networks, and newspaper coverage of lynchings in millions of issues across thousands of newspapers. I find that lynchings in counties with greater access to publicity (via rail networks) saw more and geographically dispersed coverage, that distant coverage was more critical, and that increased risk of media exposure may have reduced the incidence of lynching. I discuss how publicity could be a mechanism for strengthening or weakening justifications of violence in other contexts. ∗I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, Gareth Nellis, Elisabeth Wood, Vesla Weaver, Steven Wilkinson, Nikhar Gaikwad, as well as participants in the Yale Comparative Politics Workshop, the 2015 Politics and History conference, the 2015 American Political Science Association conference, and the 2015 Berkeley Electoral Violence conference for helpful comments and advice. I would also like to thank my research assistants|Nina Shirole, Bahja Alammari, Emily Beatty, Andi Jordan, Emil Lauritsen, Emma Lodge, and Arian Zand|for their invaluable work on this project. -

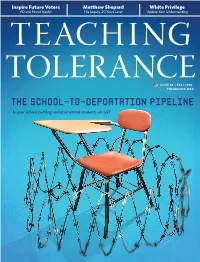

The School-To-Deportation Pipeline Is Your School Putting Undocumented Students at Risk?

Inspire Future Voters Matthew Shepard White Privilege PD and Poster Inside! His Legacy, Years Later Update Your Understanding TEACHING ISSUE | FALL TOLERANCETOLERANCE.ORG The School-to-Deportation Pipeline Is your school putting undocumented students at risk? TT60 Cover.indd 1 8/22/18 1:25 PM FREE WHAT CAN TOLERANCE. ORG DO FOR YOU? LEARNING PLANS GRADES K-12 EDUCATING FOR A DIVERSE DEMOCRACY Discover and develop world-class materials with a community of educators committed to diversity, equity and justice. You can now build and customize a FREE learning plan based on any Teaching Tolerance article! TEACH THIS Choose an article. Choose an essential question, tasks and strategies. Name, save and print your plan. Teach original TT content! TT60 TOC Editorial.indd 2 8/21/18 2:27 PM BRING SOCIAL JUSTICE WHAT CAN TOLERANCE. ORG DO FOR YOU? TO YOUR CLASSROOM. TRY OUR FILM KITS SELMA: THE BRIDGE TO THE BALLOT The true story of the students and teachers who fought to secure voting rights for African Americans in the South. Grades 6-12 Gerda Weissmann was 15 when the Nazis came for her. ONE SURVIVOR ey took all but her life. REMEMBERS Gerda Weissmann Klein’s account of surviving the ACADEMY AWARD® Holocaust encourages WINNER BEST DOCUMENTARY SHORT SUBJECT thoughtful classroom discussion about a A film by Kary Antholis l CO-PRODUCED BY THE UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM AND HOME BOX OFFICE di cult-to-teach topic. Grades 6-12 THE STORY of CÉSAR CHÁVEZ and a GREAT MOVEMENT for SOCIAL JUSTICE VIVA LA CAUSA MEETS CONTENT STANDARDS FOR SOCIAL STUDIES AND LANGUAGE VIVA LA CAUSA ARTS, GRADES 7-12. -

The Lynching of Cleo Wright

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1998 The Lynching of Cleo Wright Dominic J. Capeci Jr. Missouri State University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Capeci, Dominic J. Jr., "The Lynching of Cleo Wright" (1998). United States History. 95. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/95 The Lynching of Cleo Wright The Lynching of Cleo Wright DOMINIC J. CAPECI JR. THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1998 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 02 01 00 99 98 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Capeci, Dominic J. The lynching of Cleo Wright / Dominic J. Capeci, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Lynched for Drinking from a White Man's Well

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse this site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.× (More Information) Back to article page Back to article page Lynched for Drinking from a White Man’s Well Thomas Laqueur This April, the Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit law firm in Montgomery, Alabama, opened a new museum and a memorial in the city, with the intention, as the Montgomery Advertiser put it, of encouraging people to remember ‘the sordid history of slavery and lynching and try to reconcile the horrors of our past’. The Legacy Museum documents the history of slavery, while the National Memorial for Peace and Justice commemorates the black victims of lynching in the American South between 1877 and 1950. For almost two decades the EJI and its executive director, Bryan Stevenson, have been fighting against the racial inequities of the American criminal justice system, and their legal trench warfare has met with considerable success in the Supreme Court. This legal work continues. But in 2012 the organisation decided to devote resources to a new strategy, hoping to change the cultural narratives that sustain the injustices it had been fighting. In 2013 it published a report called Slavery in America: The Montgomery Slave Trade, followed two years later by the first of three reports under the title Lynching in America, which between them detailed eight hundred cases that had never been documented before. The United States sometimes seems to be committed to amnesia, to forgetting its great national sin of chattel slavery and the violence, repression, endless injustices and humiliations that have sustained racial hierarchies since emancipation. -

The Evolution of Racism Through the Lens of Lynching Rhetoric and Memory

THE EVOLUTION OF RACISM THROUGH THE LENS OF LYNCHING RHETORIC AND MEMORY by TAMMY BLUE ANDREW BAER, COMMITTEE CHAIR HARRIET AMOS DOSS PAMELA STERNE KING A THESIS Submitted to the graduate faculty of The University of Alabama at Birmingham, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of History BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 2020 ProQuest Number:27833348 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 27833348 Published by ProQuest LLC (2020). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All Rights Reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 THE EVOLUTION OF RACISM THROUGH THE LENS OF LYNCHING RHETORIC AND MEMORY TAMMY BLUE HISTORY ABSTRACT The Evolution of Racism Through the Lens of Lynching Rhetoric and Memory, examines the use of ‘lynching’ in its definition, legislation and politics. Rhetoric has the power to influence and persuade, therefore when public figures manipulate lynching rhetoric, the meaning of lynching becomes distorted. In part, this thesis explores the difficulty of defining lynching. Among others, key players in this process included Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Monroe Work of the Tuskegee Institute, and Jessie Daniel Ames of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching (ASWPL). -

Web Du Bois E a Revista the Crisis, 1910-1920

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA SOCIAL CARLOS ALEXANDRE DA SILVA NASCIMENTO REPRESENTANDO O “NOVO” NEGRO NORTE-AMERICANO: W. E. B. DU BOIS E A REVISTA THE CRISIS, 1910-1920 São Paulo 2015 CARLOS ALEXANDRE DA SILVA NASCIMENTO REPRESENTANDO O “NOVO” NEGRO NORTE-AMERICANO: W. E. B. DU BOIS E A REVISTA THE CRISIS, 1910-1920 Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Robert Sean Purdy São Paulo 2015 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo Nascimento, Carlos Alexandre da Silva Nascimento N244r Representando o "novo" negro norte-americano: W. E. B. Du Bois e a revista The Crisis, 1910-1920 / Carlos Alexandre da Silva Nascimento Nascimento ; orientador Robert Sean Purdy Purdy. - São Paulo, 2015. 233 f. Dissertação (Mestrado)- Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de História. Área de concentração: História Social. 1. História dos Estados Unidos . 2. Direitos Civis. 3. Afro-americano. 4. Representação. 5. W. E. B. Du Bois. I. Purdy, Robert Sean Purdy, orient. II. Título. NASCIMENTO, Carlos Alexandre da Silva. Representando o “novo” negro norte-americano Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História. -

Racial Violence, American Imperialism, and Hybrid Futurism: an Examination of the Writings of W.E.B

Racial Violence, American Imperialism, and Hybrid Futurism: An examination of the Writings of W.E.B. DuBois and Jose Martí By Webster William Heath Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in English December 15 , 2018 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Ben Tran, Ph.D. Vera M. Kutzinski, Ph.D. When engaging with theory and insight on the intellectual and social initiative towards an age of globalization, one must unavoidably address the complex conception of race and race relations around the world. During the late 19th and early 20th century North American and Latin American scholars alike, worked to understand the junction of race, class and racism as modes of domination in their environment. Most notably, W.E.B. Du Bois addressed the issue of racial exploitation, stating that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line” (The Souls of Black Folk). DuBois believed the most useful mode of social progress was an understanding of the tools used to inhibit the modern age. This sentiment was shared not only by DuBois’ English-speaking readers but by scholars all around the hemisphere. They are especially found in the writings of Cuban theorist and activist, Jose Martí. While Martí’s work was mainly towards the Cuban War for Independence from 1895-1898, he also believed that, “Men have no special rights simply because they belong to one race or another” (“Mi Raza” 172). Decolonization captures the hemispheric significance of the “color line.” When regarding the colonial experience, this paper examines the overlapping relevance of race within Martí’s Cuba as well as the United States. -

©2013 Casey Shevlin All Rights Reserved

©2013 CASEY SHEVLIN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A SYSTEM WITH PARTS AND PLAYERS: THE AMERICAN LYNCH MOB IN JOHN STEINBECK’S LABOR TRILOGY A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Casey Shevlin May, 2013 A SYSTEM WITH PARTS AND PLAYERS: THE AMERICAN LYNCH MOB IN JOHN STEINBECK’S LABOR TRILOGY Casey Shevlin Thesis Approved: Accepted: ______________________________ ______________________________ Advisor Dean of College Dr. Patrick Chura Dr. Chand Midha ______________________________ ______________________________ Committee Member Dean of Graduate School Dr. Hillary Nunn Dr. George R. Newkome ______________________________ ______________________________ Committee Member Date Dr. Julie Drew ______________________________ Department Chair Dr. William Thelin ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………1 II. “THEY’RE THE SAME ONES THAT LYNCH NEGROES”: VIGILANTES AND LYNCH MOBS IN STEINBECK’S IN DUBIOUS BATTLE……...…………………....7 III. STEINBECK’S OF MICE AND MEN: A LYNCHING NOVEL……………….….27 IV. STEINBECK’S THE GRAPES OF WRATH: LYNCHING AND RACIAL INSTABILITY IN THE 1930s WEST…………………………………………………..47 V. CONCLUDING THOUGHTS…………………………………..................................67 LITERATURE CITED.………………………………………………………………….71 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 3.1 Life Magazine Photo………………………..........……………………..………..29 iv CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION This thesis will explore the subject of lynching in John Steinbeck’s work, specifically his 1930s labor trilogy: In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), and The Grapes of Wrath (1939). My interest in John Steinbeck’s work and its connection to lynching was sparked by a particular reading of his 1937 novel, Of Mice and Men. I say particular because I have encountered the novel many times. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Race of Machines: A Prehistory of the Posthuman Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90d94068 Author Evans, Taylor Scott Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Race of Machines: A Prehistory of the Posthuman A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Taylor Scott Evans December 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Mark Minch-de Leon Mr. John Jennings, MFA Copyright by Taylor Scott Evans 2018 The Dissertation of Taylor Scott Evans is approved: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Whenever I was struck with a particularly bad case of “You Should Be Writing,” I would imagine the acknowledgements section as a kind of sweet reward, a place where I can finally thank all the people who made every part of this project possible. Then I tried to write it. Turns out this isn’t a reward so much as my own personal Good Place torture, full of desire to acknowledge and yet bereft of the words to do justice to the task. Pride of place must go to Sherryl Vint, the committee member who lived, as it were. She has stuck through this project from the very beginning as other members came and went, providing invaluable feedback, advice, and provocation in ways it is impossible to cite or fully understand. -

The Devil Is Watching You: Lynching and Southern Memory, 1940–1970

THE DEVIL IS WATCHING YOU: LYNCHING AND SOUTHERN MEMORY, 1940–1970 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by MARI N. CRABTREE August 2014 ©2014 Mari N. Crabtree ii THE DEVIL IS WATCHING YOU: LYNCHING AND SOUTHERN MEMORY, 1940–1970 Mari N. Crabtree, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2014 This dissertation is a cultural history of lynching in African American and white southern memory. Mob violence had become relatively infrequent by 1940, yet it cast a long shadow over the region in the three decades that followed. By mining cultural sources, from folklore and photographs to my own interviews with the relatives of lynching victims, I uncover the ways in which memories of lynching seeped into contemporary conflicts over race and place during the long Civil Rights Era. The protest and counter-protest movements of the 1950s and 1960s garner most of the attention in discussions of racial violence during this period, but I argue that scholars must also be attentive to the memories of lynching that register on what Ralph Ellison called “the lower frequencies” to fully understand these legacies. For instance, African Americans often shielded their children from the most painful memories of local lynchings but would pass on stories about the vengeful ghosts of lynching victims to express their disgust with these unpunished crimes. By interpreting these memories through the lenses of silence, haunting, violence, and protest, I capture a broad range of legacies, from the subtle to the overt, that illustrate how and why lynching maintained its stranglehold on southern culture. -

Springfield Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey Springfield, Illinois | August 2019 Front Cover: a Burned Riot District, August 14, 1908

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Springfield Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey Springfield, Illinois | August 2019 Front cover: A burned riot district, August 14, 1908. Photo: Unidentified photographer. Back cover: East Madison Street, August 14, 1908. Photo: Unidentified photographer. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This reconnaissance survey is a preliminary resource assessment of a site near Madison Street and the 10th Street Rail Corridor in Springfield, Illinois, associated with the 1908 Springfield Race Riot. This survey examines the likelihood that the study area would meet the four established criteria for inclusion in the national park system: national significance, suitability, feasibility, and need for direct National Park Service (NPS) management. Conclusions provided in reconnaissance surveys do not determine whether a study area is eligible for inclusion in the national park system. If a reconnaissance survey finds that a study area is likely to meet the NPS criteria for inclusion, then a special resource study may be recommended. Special resource studies are more detailed reports that provide Congress with critical information used in the process of designating new units of the national park system. The study area examined in this reconnaissance survey contains the structural remains of five homes that were burned during the 1908 Springfield Race Riot. The resources were identified in 2014 by archeologists during phase II investigations for a Federal Railroad Administration project called the Carpenter Street Underpass Project. Following those investigations, the Federal Railroad Administration, along with the Illinois State Historic Preservation Office determined that the archeological site is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places under both criterion A (associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history) and criterion D (yielded or may be likely to yield, information important in history or prehistory).