Delhi Dialogue Vii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Explosion

ARUNACHAL A monthly english journal SEPTEMBER 2019 1 REVIEW Population Explosion: A stark reality in India - Denhang Bosai s the nation was blissfully this rate then we are in for a If the people continue to Aand deeply engrossed in very serious problems ahead. be defiant and are not both- euphoric celebration of scrap- The problem will truly ered by the huge problems the ping of Article 370 and 35 (A) be catasthropic country is facing today due to from Jammu and Kashmir, having far- uncontrolled population growth many fail to listen to the very reaching dev- then GOI may explore possibil- relevant and important issue of astating con- ities to enact a uniform law in 'population explosion' raised by sequences. It consultation with all the people PM Modi in his Independence will be too late to check population Day speech this year. for us even to explo- sion. The The Prime repent. G O I Minister very rightly must en- opined that main- sure that taining a small the law will family can also be applicable be patriotism. He to all Indians said that patriotic irrespective of Indians should vol- religions or regions. unteer to have small Today, India produces families by having less huge quantities of food grains, children even though there build many roads, railways, was no law for it. How true schools, colleges, hospitals indeed, because this is in A l l and other facilities but they the interest of the nation. Indians ir- are never enough for the bil- Population explosion respective of lions of Indians. -

Climate Change and Organic Agriculture

1 INSIDE Editorial - Climate Change In The Eastern Himalayan Region Climate Change and Organic Agriculture My Experience with Inhana Rational Farming Technology The Impact of Climate Change on Quality of Tea and Livelihoods in the North East of India Climate Change: A Major Challenge for Sustaining Crop Production in North Eastern India Combating Climate Change the Subaltern Way : In Conversation with Dunu Roy Organic News Source:Source: Foodwhatsyourimpact.org and Agricultural Organization, United Nations. CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE EASTERN HIMALAYAN REGION The Eastern Himalayan region is spread (about 144) are found particularly in the a 1 degree Celsius increase in temperature in over five countries, namely, Bhutan, China, North Eastern states of India. the Himalayas, will have extensive impact not India, Myanmar and Nepal. The region, with only on the mountainous regions but also on It has been widely noted that mountains make its varied geopolitical and socioeconomic for fragile environments and any alterations in the northern river-plains that depend largely systems has been home to diverse cultures climatic conditions would have far-reaching on them. and ethnic groups alongside encompassing impact on the ecosystems that are sustained immense natural resources, rich forest cover, Additionally, political alliances between by them. As a repository of biodiversity and assorted biodiversity and numerous species countries of the subcontinent are dependent ecosystems, the Eastern Himalayan region is of medicinal herbs and plants. The region’s in a significant way on these trans-border also a sanctuary for many endangered and complex topographical layout has given rise rivers. As a result, the impact of climate endemic species. -

The FIC-NCR Newsletter

The FIC-NCR Newsletter First Issue FIC-NCR 1 Message from the President Art Retos I would like to welcome all of you to the maiden issue of the first-ever FIC-NCR newsletter. As your chosen leader, I am delighted to start this initiative, which is one of the legacies I want to leave behind if only because I believe it can help bring us closer together as a community. For this same reason, I hope that the next FIC-NCR president will continue this initiative and make it better. When you elected me as FIC-NCR President, it took awhile before that title sink in. Leading our very diverse group was a thought that didn’t occur to me nor did I plan for it. Then oath-taking day came and officially I have become your President. That’s when I started to dig deep in my thoughts on how best I could lead us towards achieving one goal: building a closer and more united Filipino community in the national capital region of India. I went back in time when there’s no formal Filipino association, no presidents nor officers, just good old times at which Filipinos from Gurgaon came to Delhi or vice versa for our weekly potluck lunches. The theme “Balik Saya” jelled in my mind. I wanted to keep bringing the fun back to our community, even turn it up a notch, through activities with which Filipi- nos from different parts of the NCR would come together – sharing food and company, jokes and entertainment -- all geared towards our common goal. -

Report on Two Day International Webinar on Impact of Covid-19

Report on ‘Two Day International Webinar on ‘Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Global Economy’ 22-23 June, 2020 Organised by Centre for Development Studies Department of Economics Rajiv Gandhi University, Arunachal Pradesh Part – I Organising Committee Chief Patron Prof. Saket Kushwaha, Vice-Chancellor, Rajiv Gandhi University Patrons Prof. Amitava Mitra, Pro Vice-Chancellor, Rajiv Gandhi University Prof. Tomo Riba, Registrar, Rajiv Gandhi University Advisors Prof. Tana Showren, Dean, Faculty of Social Sciences Prof. N.C. Roy, Professor, Department of Economics Prof. S.K. Nayak, Professor, Department of Economics Organising Chairperson/Convener Prof. Vandana Upadhyay, Head, Professor, Department of Economics Coordinator Dr. Maila Lama, Sr. Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Deputy Coordinator Dr. Dil. B. Gurung Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Assistant Coordinators Dr. Lijum Nochi, Sr. Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Dr. Anup Kr. Das, Sr. Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Dr. Prasenjit B. Baruah, Sr. Assistant Professor, Department of Economics 1 Part – II Seminar/ Workshop / Webinar / FDP /STPs etc. 2.1: Background / Concept Notes and Objectives The world has been affected by the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic since November 2019. The virus causes respiratory diseases in human beings from common cold to more rare and serious diseases such as the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), both of which have high mortality rates (WHO 2020). The UN Secretary General described it as the worst crisis being faced by mankind since World War-II. It may lead to enhanced instability, unrest and enhanced conflict (The Economic Times, April 1, 2020). There is a high risk associated with this disease as it is highly fatal and contagious. -

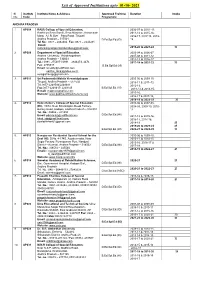

List of Approved Institutions Upto 11-08

List of Approved Institutions upto 01-10- 2021 Sl. Institute Institute Name & Address Approved Training Duration Intake No. Code Programme ANDHRA PRADESH 1. AP004 RASS College of Special Education, 2006-07 to 2010 -11, Rashtriya Seva Samiti, Seva Nilayram, Annamaiah 2011-12 to 2015-16, Marg, A.I.R. Bye – Pass Road, Tirupati, 2016-17, 2017-18, 2018- Andhra Pradesh – 517501 D.Ed.Spl.Ed.(ID) 19, Tel No.: 0877 – 2242404 Fax: 0877 – 2244281 Email: [email protected]; 2019-20 to 2023-24 30 2. AP008 Department of Special Education, 2003-04 to 2006-07 Andhra University, Vishakhapatnam 2007-08 to 2011-12 Andhra Pradesh – 530003 2012-13 to 2016-17 Tel.: 0891- 2754871 0891 – 2844473, 4474 2017-18 to 2021-22 30 Fax: 2755547 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(VI) Email: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] 3. AP011 Sri Padmavathi Mahila Visvavidyalayam , 2005-06 to 2009-10 Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh – 517 502 2010-11 & 2011–12 Tel:0877-2249594/2248481 2012-13, Fax:0877-2248417/ 2249145 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) 2013-14 & 2014-15, E-mail: [email protected] 2015-16, Website: www.padmavathiwomenuniv.org 2016-17 & 2017-18, 2018-19 to 2022-23 30 4. AP012 Helen Keller’s College of Special Education 2005-06 to 2007-08, (HI), 10/72, Near Shivalingam Beedi Factory, 2008-09, 2009-10, 2010- Bellary Road, Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh – 516 001 11 Tel. No.: 08562 – 241593 D.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) Email: [email protected] 2011-12 to 2015-16, [email protected]; 2016-17, 2017-18, [email protected] 2018-19 25 2019-20 to 2023-24 25 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) 2020-21 to 2024-25 30 5. -

Sustainable Local Firms Get Avenue for Tie-Ups

THURSDAY, MAY 13, 2021 Intelligent . In-depth . Independent Issue Number 3662 / 4000 RIEL FORMER TV HOST EXPORT OF CASSAVA, LATE INCENTIVES IN ACCUSES TYCOON CASHEW, MANGO TO INDONESIA TORMENT OF RAPE ATTEMPT VIETNAM RISES 149% FRONT-LINE WORKERS NATIONAL – page 5 BUSINESS – page 6 WORLD – page 10 Sustainable local firms get avenue for tie-ups May Kunmakara Delivering the event’s open- ing remarks, CDC secretary- AMBODIA, with sup- general Sok Chenda Sophea port from the World said SD2 will better equip in- Economic Forum ternational investors to seize (WEF), on May 12 investment opportunities and launchedC the Supplier Data- strike partnerships with suit- base with Sustainability able domestic companies. Dimensions (SD2) database, “We hope that investors and the first of its kind, to provide foreign firms will see that Cam- information on the sustaina- bodia is creating a welcoming bility operations of domestic investment climate, while be- companies. SD2 will serve as a ing committed to responsible key platform linking interna- and sustainable business. tional and domestic firms that “As a relatively small coun- invest in the Kingdom or are try, Cambodia can set itself seeking new partnerships. apart by being a pioneer in fa- An in-person and virtual cilitating sustainable invest- ceremony was hosted by the ment,” he said. “We invite all Council for the Development investors to use SD2 and find of Cambodia (CDC) and WEF qualified domestic partners.” Power boost to commemorate the launch, Matthew Stephenson, a Electricite du Cambodge (EdC) engineers on a boom lift perform service checks on a utility pole in a red zone of Meanchey STORY > 4 district’s Stung Meanchey commune on Tuesday. -

Standing Committee on Urban and Rural Development (1999-2000) 14

STANDING COMMITTEE ON URBAN AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (1999-2000) 14 THIRTEENTH LOK SABHA THE CONSTITUTION (EIGHTY-SIXTH AMENDMENT) BILL, 1999 FOURTEENTH REPORT Presented to Lok Sabha on 26-7-2000 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 2-7-2000 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CONTENTS COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE INTRODUCTION PART I Background of the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Bill, 1999 PART II Analysis of the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Bill, 1999 APPENDICES I. The Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Bill, 1999, as introduced in Rajya Sabha II. The copy of the opinion dated 24th October, 1997 of the Department of Legal Affairs on Arunachal Pradesh Panchayat Raj Bill, 1997 III. The copy of the opinion dated 31st March, 2000 of the Department of Legal Affairs regarding applicability of article 243 D IV. Minutes of the Sixth sitting of the Committee held on 8th March, 2000 V. Minutes of the Seventeenth sitting of the Committee held on 10th May, 2000 VI. Minutes of the Nineteenth sitting of the Committee held on 8th June, 2000 VII. Minutes of the Twentieth sitting of the Committee held on 21st July, 2000 VIII. Statement of Recommendations/Observations COMPOSITION OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON URBAN AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (1999-2000) Shri Anant Gangaram Geete - Chairman MEMBERS Lok Sabha 2. Shri Mani Shankar Aiyar 3. Shri Padmanava Behera 4. Shri Jaswant Singh Bishnoi 5. Shri A. Brahmanaiah 6. Shri Swadesh Chakrabortty 7. Shri Haribhai Chaudhary 8. Shri Bal Krishna Chauhan 9. Shri Chinmayanand Swami 10. Prof. Kailasho Devi 11. Shrimati Hema Gamang 12. Shri Holkhomang Haokip 13. Shri R.L. -

Provisional List of Participants

8 December 2009 ENGLISH/FRENCH/SPANISH ONLY UNITED NATIONS FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Fifteenth session Copenhagen, 7–18 December 2009 Provisional list of participants Part One Parties 1. The attached provisional list of participants attending the fifteenth session of the Conference of the Parties, and the fifth session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol, as well as the thirty-first sessions of the subsidiary bodies, has been prepared on the basis of information received by the secretariat as at Friday, 4 December 2009. 2. A final list of participants will be issued on Friday, 18 December 2009, taking into account additional information received by the secretariat prior to that date and including any corrections submitted. Corrections should be given to Ms. Heidi Sandoval (Registration counter) by 12 noon, at the latest, on Wednesday, 16 December 2009. 3. Because of the large number of participants at this session, the provisional list of participants is presented in three parts. FCCC/CP/2009/MISC.1 (Part 1) GE.09-70998 - 2 - Participation statistics States/Organizations Registered participants Parties 191 8041 Observer States 3 12 Total Parties + observer States 194 8053 Entities having received a standing invitation to 1 11 participate as observers in the sessions and the work of the General Assembly and maintaining permanent observer missions at Headquarters United Nations Secretariat units and bodies 33 451 Specialized agencies and related organizations 18 298 Intergovernmental organizations 53 699 Non-governmental organizations 832 20611 Total observer organizationsa 937 22070 Total participation 30123 Registered media 1069 2941 a Observer organizations marked with an asterisk (*) in this document have been provisionally admitted by the Bureau of the Conference of the Parties. -

Organic 6.Indd

1 IINSIDENSIDE EEditorialditorial - TThehe GGoodood EEartharth IInternationalnternational YYearear ooff SSoils:oils: LLetsets TToiloil FForor OOurur SSoils!oils! SSoil:oil: NNature’sature’s MMostost PPreciousrecious GGiftift AAfterfter WWaterater IInhananhana RRationalational FFarmingarming TTechnology:echnology: A NNewew IInitiativenitiative TTowardsowards HHathikuliathikuli SSustainabilityustainability NNorth-Eastorth-East ooff IIndiandia - CCradleradle ooff NNaturenomicsaturenomicsTTMM* BBackack ttoo tthehe FFuture:uture: A CConversationonversation wwithith AAparajitaparajita SSenguptaengupta OOrganicrganic NNewsews UUnlocknlock tthehe SSecretsecrets oonn tthehe SSoiloil TThingshings YYouou CCanan DDoo ttoo IImprovemprove SSoiloil HHealthealth SSource:ource: FFoodood aandnd AAgriculturalgricultural OOrganization,rganization, UUnitednited NNations.ations. 2 THE GOOD EARTH Healthy soil is the foundation of the food even in small amounts, organic matter is very occurred in sustained food production system. It produces healthy crops that in important. such as increased plant productivity, increased turn nourish people. Maintaining a healthy fertilizer efficiency, reduced waterlogging, Soil is a living, dynamic ecosystem. I soil demands care and effort from farmers increased yields, reduced herbicide and firmly believe that by adding organic matter because farming is not benign. By definition, pesticide use, increased biodiversity and to the soil and improving the structure, farming disturbs the natural soil processes improving soil properties -

ICICI Interm Dividend.Xlsx

Baid Leasing and Finance Co. Ltd. Regd. Office: “Baid House”, IInd Floor, 1-Tara Nagar, Ajmer Road, Jaipur-06 Ph:9214018855 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.balfc.comCIN: L65910RJ1991PLC006391 STATEMENT OF UNPAID AND UNCLAIMED INTERIM DIVIDEND AS ON 31.12.2018 (OCTOBER 2016) CURRENT S. NO PAYEE Name ADDRESS AMOUNT STATUS 1 A DULICHAND CHHAJER 5 Valkunda Vathiyar Street Sowcarpet Chennai 600079 50.00 UNPAID 2 A K VISWANATHAN H/2 Periyar Nagar Erode Tamilnadu 638009 150.00 UNPAID Thavakkal House Azad Nagar Managad Lane Karamana 3 A S NOORUDEEN 50.00 UNPAID Thiruvananthapuram 695003 4 A. MAJID YUSUF MALEK Kohinoor Apartment 2Nd Floor Juna Darbar Nanpura Surat 395001 150.00 UNPAID 5 AAKASH MEHTA 1488-5 Old Madhupura Ahmedabad Gujrat 380004 100.00 UNPAID 6 ABDUL JIVA THASARIA Kadiakumbhar Street Mahendrapara Morbi 363641 Gujrat 0 50.00 UNPAID 7 ABDUL MALIK C-107 Shivaji Marg Tilak Nagar Jaipur 302004 Rajasthan 0 50.00 UNPAID 8 ABEDA BANU KUKDA C/O Molani Saree Palace Sujangarh Rajasthan 331507 150.00 UNPAID 9 ABHA VARSHNEY 12 Transet Hostel Colony I J K Cement Raj Nimbahera 312617 50.00 UNPAID 10 ABHILASHA KANODIA C/O I K Kanodia 7-A-24 R C Vyas Colony Bhilwara 311001 Rajasthan 0 150.00 UNPAID 11 ABHISHEK JAIN 1110 Near Mahavir Park Kishan Pole Bazzar Jaipur 302003 Rajasthan 0 50.00 UNPAID 12 ADALE PATEL H 24 Cusrow Baug Colaba Bombay Maharastra 400039 100.00 UNPAID 13 ADARSH BOELA 3047/D-1 Street No 21 Ranjit Nagar Patel Nagar New Delhi New Delhi 0 50.00 UNPAID 14 ADITI SAHU C/O Sidhartha Sahu Karanjia Mayurbhanj Orissa 757037 -

Philippine Navy Anniversary

RoughTHE OFFICIALDeck GAZETTE OF THE PHILIPPINE NAVYLog • VOLUME NO. 89 • MAY 2020 Strong & Credible: nd Philippine Navy in 2020 p. 8 Jose Rizal, aboard 122 p. 10 Charting the Future through PHILIPPINE NAVY PN Information Warfare Systems Strategy ANNIVERSARY p. 22 Combating COVID-19 Philippine Marine Corps’ Response to Pandemic p. 30 PN ROUGHDECKLOG 1 14 Feature Articles RoughDeckLog 8 Strong & Credible: Philippine Navy in 2020 10 Jose Rizal, aboard 12 Sailing with Perseverance & Determination 14 The PN Seabees: Sailing along with the Navy in these Editorial Board 122nd Philippine Navy Anniversary Theme: Turbulent Times VADM GIOVANNI CARLO J BACORDO AFP 16 Team NAVFORSOL: The Philippines Navy’s Vanguard against COVID-19 in Southern Luzon Flag Officer In Command, Philippine Navy Sailing these turbulent times 18 Naval Forces Central: Sailing amid turbulent times RADM REY T DELA CRUZ AFP The Navy’s Role During the Pandemic Vice Commander, Philippine Navy towards our Maritime Nation’s 20 A Lighthouse in the Midst: OTCSN's Role in Health RADM ADELUIS S BORDADO AFP Management in the PN Chief of Naval Staff Defense and Development 22 Charting the Future through PN Information Warfare COL EDWIN JOSEPH H OLAER PN(M)(MNSA) Systems Strategy Assistant Chief of Naval Staff for Civil Military 42 23 Naval ICT Center: Committed to Innovation & Service Operations, N7 Contributors Excellence CAPT MARCOS Y IMPERIO PN(GSC) 26 Philippine Navy CMO sailing towards our Maritime Nation’s Development Editorial Staff LTCOL TINO P MASLAN PN(M)(GSC) Editor-In-Chief MAJ EMERY L TORRE PN(M) 27 Back to the People: Transitioning the Community Support Program on Paly Island, Palawan LCDR MARIA CHRISTINA A ROXAS PN LT JOSE L ANGELES III PN LT MAIVI B NERI PN 23 29 We build as one, We heal as one! Editorial Assistants CPT JOEMAR T JESURA PN(M) LCDR ENRICO T PAYONGAYONG PN 30 Combating COVID-19 1LT REGIN P REGALADO PN(M) Philippine Marine Corps’ Response to Pandemic LCDR RYAN H LUNA PN ENS ROVI MAIREL D MARTINEZ PN LCDR RANDY P GARBO PN Engr. -

STATISTICAL REPORT GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1998 the 12Th LOK

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1998 TO THE 12th LOK SABHA VOLUME II (CONSTITUENCY DATA - SUMMARY) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 1998 (12th LOK SABHA) STATISCAL REPORT – VOLUME II (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 5 2. Number and Types of Constituencies 6 - 548 Election Commission of India-General Elections, 1998 (12th LOK SABHA) LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY 2 . BSP BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY 3 . CPI COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA 4 . CPM COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST) 5 . INC INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 6 . JD JANATA DAL 7 . SAP SAMATA PARTY STATE PARTIES 8 . AC ARUNACHAL CONGRESS 9 . ADMK ALL INDIA ANNA DRAVIDA MUNNETRA KAZHAGAM 10 . AGP ASOM GANA PARISHAD 11 . AIIC(S) ALL INDIA INDIRA CONGRESS (SECULAR) 12 . ASDC AUTONOMOUS STATE DEMAND COMMITTEE 13 . DMK DRAVIDA MUNNETRA KAZHAGAM 14 . FBL ALL INDIA FORWARD BLOC 15 . HPDP HILL STATE PEOPLE'S DEMOCRATIC PARTY 16 . HVP HARYANA VIKAS PARTY 17 . JKN JAMMU & KASHMIR NATIONAL CONFERENCE 18 . JMM JHARKHAND MUKTI MORCHA 19 . JP JANATA PARTY 20 . KEC KERALA CONGRESS 21 . KEC(M) KERALA CONGRESS (M) 22 . MAG MAHARASHTRAWADI GOMANTAK 23 . MNF MIZO NATIONAL FRONT 24 . MPP MANIPUR PEOPLE'S PARTY 25 . MUL MUSLIM LEAGUE KERALA STATE COMMITTEE 26 . NTRTDP(LP) NTR TELUGU DESAM PARTY (LAKSHMI PARVATHI) 27 . PMK PATTALI MAKKAL KATCHI 28 . RPI REPUBLICAN PARTY OF INDIA 29 . RSP REVOLUTIONARY SOCIALIST PARTY 30 . SAD SHIROMANI AKALI DAL 31 . SDF SIKKIM DEMOCRATIC FRONT 32 .