Audit of Use of Stiripentol in Adults with Dravet Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stiripentol with an Average Age of 9.1 Years

VOLUME 43 : NUMBER 3 : JUNE 2020 NEW DRUGS The other trial was in Italy and involved 23 children Stiripentol with an average age of 9.1 years. After two months, eight children responded to stiripentol (66.7%). Aust Prescr 2020;43:102 Approved indication: Dravet syndrome Only one (9.1%) in the placebo group responded. https://doi.org/10.18773/ Diacomit (Emerge Health) Three of the children taking stiripentol became free austprescr.2020.029 250 mg and 500 mg capsules of seizures.2 First published 250 mg and 500 mg powder for oral suspension During the trials there were more adverse events in 24 April 2020 Dravet syndrome is a severe myoclonic epilepsy in the children taking stiripentol, compared to placebo. infancy. It usually emerges in the first year of life. More frequent effects included drowsiness, agitation, The seizures are difficult to control and the infants irritability, hypotonia, nausea and vomiting. There develop intellectual disability. Stiripentol has been was also loss of appetite and weight loss. Elevation approved as an adjunctive treatment for infants with of gamma-glutamyltransferase has been reported so generalised tonic-clonic and clonic seizures which are liver function should be checked every six months, not controlled by valproate and a benzodiazepine. as should a full blood count because of the risk of neutropenia. Stiripentol is an aromatic alcohol which is unrelated to the structure of other antiepileptic drugs. It While it is difficult to know if the effect is due to its increases activity in the GABAergic system, but it also interaction with clobazam and valproate, stiripentol interacts with anticonvulsant drugs. -

10|18 Stiripentol Use in Children with Refractory Seizures

PEDIATRIC PHARMACOTHERAPY Volume 24 Number 10 October 2018 Stiripentol Use in Children with Refractory Seizures Marcia L. Buck, PharmD, FCCP, FPPAG, BCPPS tiripentol was approved by the Food and concentrations of 2, 6.5, and 14.1 mg/L between S Drug Administration (FDA) on August 20, 2 and 4 hours post-dose.6 The drug is highly 2018 as adjunctive therapy with clobazam for the protein bound (99%), with an estimated treatment of seizures associated with Dravet elimination half-life of 5 to 13 hours. Although syndrome in patients 2 years of age and older.1,2 It the metabolism of stiripentol has not been fully is not currently approved as monotherapy. Dravet delineated, it is known to be a substrate for syndrome, also referred to as severe myoclonic CYP1A2, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4. As a result of epilepsy of infancy, is a rare disorder its reliance on both hepatic and renal clearance, characterized by seizures unresponsive to most use of stiripentol in patients with moderate to antiepileptics, motor impairment, and severe hepatic or renal impairment is not developmental disabilities. Nearly a quarter of recommended.2 patients die during childhood. Approximately 70% of patients have a mutation in the sodium The first published study to evaluate stiripentol channel alpha-1 subunit gene (SCN1A) leading to plasma concentrations enrolled 10 children and malfunction or loss of function in GABAergic adolescents from 6 to 16 years of age with neurons.3 As a treatment for a rare disorder, refractory atypical absence seizures.7 The patients stiripentol has been designated as an orphan drug received a mean maintenance dose of 57 by both the European Medicines Agency and the mg/kg/day (range 34-78 mg/kg/day) during the 4- FDA. -

Preferred Drug List 4-Tier

Preferred Drug List 4-Tier 21NVHPN13628 Four-Tier Base Drug Benefit Guide Introduction As a member of a health plan that includes outpatient prescription drug coverage, you have access to a wide range of effective and affordable medications. The health plan utilizes a Preferred Drug List (PDL) (also known as a drug formulary) as a tool to guide providers to prescribe clinically sound yet cost-effective drugs. This list was established to give you access to the prescription drugs you need at a reasonable cost. Your out- of-pocket prescription cost is lower when you use preferred medications. Please refer to your Prescription Drug Benefit Rider or Evidence of Coverage for specific pharmacy benefit information. The PDL is a list of FDA-approved generic and brand name medications recommended for use by your health plan. The list is developed and maintained by a Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee comprised of actively practicing primary care and specialty physicians, pharmacists and other healthcare professionals. Patient needs, scientific data, drug effectiveness, availability of drug alternatives currently on the PDL and cost are all considerations in selecting "preferred" medications. Due to the number of drugs on the market and the continuous introduction of new drugs, the PDL is a dynamic and routinely updated document screened regularly to ensure that it remains a clinically sound tool for our providers. Reading the Drug Benefit Guide Benefits for Covered Drugs obtained at a Designated Plan Pharmacy are payable according to the applicable benefit tiers described below, subject to your obtaining any required Prior Authorization or meeting any applicable Step Therapy requirement. -

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants INTRODUCTION • Epilepsy is a disease of the brain defined by any of the following (Fisher et al 2014): At least 2 unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring > 24 hours apart; 1 unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least ○ 60%) after 2 unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years; ○ Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome. • Types of seizures include generalized seizures, focal (partial) seizures, and status epilepticus (Centers for Disease Control○ and Prevention [CDC] 2018, Epilepsy Foundation Greater Chicago 2020). Generalized seizures affect both sides of the brain and include: . Tonic-clonic (grand mal): begin with stiffening of the limbs, followed by jerking of the limbs and face ○ . Myoclonic: characterized by rapid, brief contractions of body muscles, usually on both sides of the body at the same time . Atonic: characterized by abrupt loss of muscle tone; they are also called drop attacks or akinetic seizures and can result in injury due to falls . Absence (petit mal): characterized by brief lapses of awareness, sometimes with staring, that begin and end abruptly; they are more common in children than adults and may be accompanied by brief myoclonic jerking of the eyelids or facial muscles, a loss of muscle tone, or automatisms. Focal seizures are located in just 1 area of the brain and include: . Simple: affect a small part of the brain; can affect movement, sensations, and emotion, without a loss of ○ consciousness . Complex: affect a larger area of the brain than simple focal seizures and the patient loses awareness; episodes typically begin with a blank stare, followed by chewing movements, picking at or fumbling with clothing, mumbling, and performing repeated unorganized movements or wandering; they may also be called “temporal lobe epilepsy” or “psychomotor epilepsy” . -

Primidone SERB 50Mg and 250Mg Tablets Primidone

B. PACKAGE LEAFLET Package leaflet: Information for the user Primidone SERB 50mg and 250mg Tablets Primidone Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this medicine because it contains important information for you. - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. - If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. - This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor, or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet: 1. What Primidone is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you take Primidone SERB 3. How to take Primidone SERB 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Primidone SERB 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Primidone SERB is and what it is used for Primidone contains primidone as the active ingredient; this belongs to a group of medicines used to treat seizures. Primidone is used for the treatment of certain types of epilepsy, seizures (fits) or shaking attacks (essential tremor). 2. What you need to know before you take Primidone SERB Do not take Primidone: If you are allergic to primidone, phenobarbital, or to any of the other ingredients of this medicine (these are listed in Section 6: Further information). If you have porphyria (a rare inherited disorder of metabolism) or anyone in your family has it. -

Utah Medicaid Dur Report March 2019

UTAH MEDICAID DUR REPORT MARCH 2019 CANNABIDIOL AND STIRIPENTOL FOR THE TREATMENT OF SEIZURES ASSOCIATED WITH LENNOX-GASTAUT AND DRAVET SYNDROMES Cannabidiol Oral Solution (Epidiolex) Stiripentol Oral Capsule and Powder for Oral Suspension (Diacomit) Report finalized: February 2019 Drug Regimen Review Center Elena Martinez Alonso, B.Pharm., MSc MTSI, Medical Writer Valerie Gonzales, Pharm.D., Clinical Pharmacist Lauren Heath, Pharm.D., MS, BCACP, Assistant Professor (Clinical) Vicki Frydrych, B.Pharm., Pharm.D., Clinical Pharmacist Jacob Crook, MStat, Data and Statistical Analyst Joanne LaFleur, PharmD, MSPH, Associate Professor University of Utah College of Pharmacy, Drug Regimen Review Center Copyright © 2019 by University of Utah College of Pharmacy Salt Lake City, Utah. All rights reserved Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Methods .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Disease Overview ............................................................................................................................ 2 Table 1. ILAE Multilevel Classification of Epilepsies ............................................................... 3 Table 2. Diagnosis of Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome ................................................................... 6 Table 3. Diagnosis of Dravet Syndrome ................................................................................. -

Stiripentol for Continuation in Adults with Dravet Syndrome (PDF)

North Central London Joint Formulary Committee Shared Care Guideline for continuation of stiripentol in adults with Dravet syndrome Dear GP The information in the shared care guideline has been developed in consultation with Primary Care and it has been agreed that it is suitable for shared care. Sharing of care assumes communication between the specialist, GP and patient. The intention to share care should be explained to the patient by the Consultant when treatment is initiated. It is important that patients are consulted about treatment and are in agreement with it. Contents 1. Introduction Target audience ............................................................................................................... 2 2. Shared Care criteria .............................................................................................................................. 2 3. Shared care responsibilities .................................................................................................................. 3 3.1. Consultant and /or Specialist Nurse ............................................................................................. 3 3.2. General Practitioner ..................................................................................................................... 3 3.3. Patient responsibility .................................................................................................................... 4 3.4. Clinical Commissioning Group ..................................................................................................... -

New Antiepileptic Drugs

Chapter 29 New antiepileptic drugs J.W. SANDER UCL Institute of Neurology, University College London, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London, and Epilepsy Society, Chalfont St Peter, Buckinghamshire New antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are necessary for people with chronic epilepsy and for improving upon established AEDs as first-line therapy. Since 2000, ten new AEDs have been released in the UK. In chronological order these are: oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam, pregabalin, zonisamide, stiripentol, rufinamide, lacosamide, eslicarbazepine acetate, retigabine and perampanel. Two of these drugs, stiripentol and rufinamide, are licensed as orphan drugs for specific epileptic syndromes. Another drug, felbamate, is available in some EU countries. Their pharmacokinetic properties are listed in Table 1 and indications and a guide to dosing in adults and adolescents are given in Table 2. Known side effects are given in Table 3. Complete freedom from seizures with the absence of side effects should be the ultimate aim of AED treatment and the new AEDs have not entirely lived up to expectations. Only a small number of people with chronic epilepsy have been rendered seizure free by the addition of new AEDs. Despite claims to the contrary, the safety profile of the new drugs is only slightly more favourable than that of the established drugs. The chronic side effect profile for the new drugs has also not yet been fully established. New AEDs marketed in the UK Eslicarbazepine acetate Eslicarbazepine acetate is licensed as an add-on for focal epilepsy. It has similarities to carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. As such it interacts with voltage-gated sodium channels and this is likely to be its main mode of action. -

Diacomit, INN-Stiripentol

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Diacomit 250 mg hard capsules 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each capsule contains 250 mg of stiripentol. Excipients: 0.16 mg sodium per capsule. For a full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Hard capsules Size 2 pink capsule 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Diacomit is indicated for use in conjunction with clobazam and valproate as adjunctive therapy of refractory generalized tonic-clonic seizures in patients with severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (SMEI, Dravet’s syndrome) whose seizures are not adequately controlled with clobazam and valproate. 4.2 Posology and method of administration Diacomit should only be administered under the supervision of a paediatrician / paediatric neurologist experienced in the diagnosis and management of epilepsy in infants and children. The capsule should be swallowed whole with a glass of water during a meal. The dose of Diacomit is calculated on a mg/kg body weight basis. The daily dosage may be administered in 2 or 3 divided doses. The initiation of adjunctive therapy with Diacomit should be undertaken over 3 days using upwards dose escalation to reach the recommended dose of 50 mg/kg/day administered in conjunction with clobazam and valproate. This recommended dose is based on the available clinical study findings and was the only dose of Diacomit evaluated in the pivotal studies (see section 5.1). There are no clinical study data to support the clinical safety of Diacomit administered at daily doses greater than 50 mg/kg/day. -

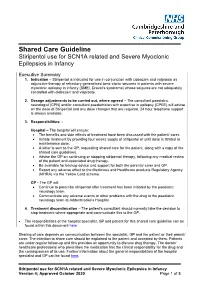

Shared Care Guideline Stiripentol Use for SCN1A Related and Severe Myoclonic Epilepsies in Infancy

Shared Care Guideline Stiripentol use for SCN1A related and Severe Myoclonic Epilepsies in Infancy Executive Summary 1. Indication – Stiripentol is indicated for use in conjunction with clobazam and valproate as adjunctive therapy of refractory generalized tonic-clonic seizures in patients with severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (SMEI, Dravet’s syndrome) whose seizures are not adequately controlled with clobazam and valproate. 2. Dosage adjustments to be carried out, where agreed – The consultant paediatric neurologist (CPN) and/or consultant paediatrician with expertise in epilepsy (CPEE) will advise on the dose of Stiripentol and any dose changes that are required. 24 hour telephone support is always available. 3. Responsibilities: - Hospital – The hospital will ensure: • The benefits and side effects of treatment have been discussed with the patient/ carer. • Initiate treatment by providing four weeks supply of stiripentol or until dose is titrated to maintenance dose. • A letter is sent to the GP, requesting shared care for the patient, along with a copy of the shared care guidelines. • Advise the GP on continuing or stopping stiripentol therapy, following any medical review of the patient and associated drug therapy. • Be available for backup advice and support for both the parents/ carer and GP. • Report any adverse effect to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) via the Yellow Card scheme. GP - The GP will: • Continue to prescribe stiripentol after treatment has been initiated by the paediatric neurology team. • Communicate any adverse events or other problems with the drug to the paediatric neurology team at Addenbrooke’s Hospital. 4. Treatment discontinuation – The patient’s consultant should normally take the decision to stop treatment where appropriate and communicate this to the GP. -

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information No

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information No. 298 January 2013 Table of Contents 1. Partial Amendment of the “Guidance for Bar Code Labeling on Prescription Drugs” for the Prevention of Medical Accidents .......... 5 2. Important Safety Information ..................................................................... 11 (1) Temozolomide .............................................................................................. 11 (2) Telaprevir ...................................................................................................... 13 (3) Pramipexole Hydrochloride Hydrate............................................................. 20 (4) Mogamulizumab ........................................................................................... 23 3. Revision of Precautions (No. 242) .......................................................... 28 Digoxin, Deslanoside, and Methyldigoxin (and 5 others) ................................ 28 4. List of Products Subject to Early Post-marketing Phase Vigilance .................................................. 30 This Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information (PMDSI) is issued based on safety information collected by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). It is intended to facilitate safer use of pharmaceuticals and medical devices by healthcare providers. The PMDSI is available on the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) website (http://www.pmda.go.jp/english/index.html) and on the MHLW website (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/, only available -

PDL)/Non-Preferred Drug List (NPDL

Louisiana Medicaid Preferred Drug List (PDL)/Non-Preferred Drug List (NPDL) • The PDL is a list of over 100 therapeutic classes reviewed by the Pharmaceutical & Therapeutics (P&T) committee. In addition, there are medications and/or classes of medications that are not reviewed by the committee. Unless there is a clinical pre-authorization requirement for the entire class (as noted on the last page of the PDL) these medications will continue to be covered without prior authorization. Examples: spironolactone, hydrochlorothiazide, amoxicillin suspension • To locate any medication on this list, you may use the keyboard shortcut CTRL + F to search. • There is a mandatory generic substitution unless the brand is preferred, and the generic is non-preferred. When the brand is preferred and the generic is non-preferred, no special notations are required by the prescriber and the pharmacist enters “9” in the DAW field 408-D8. • When the brand is non-preferred and the prescriber has determined it to be medically necessary, “Brand medically necessary” or “Brand necessary” must be written on the prescription in the prescriber’s handwriting or via an electronic prescription and the pharmacist enters “1” in the DAW field 408-D8. For more information, please CLICK THIS LINK to the provider manual. • New medications that enter the marketplace in classes reviewed by P&T committee will be considered non-preferred requiring prior authorization until the next P&T committee meeting. Please refer to the following criteria: New Drugs Introduced into the Market / Non-Preferred • Medications listed as non-preferred are available through the prior authorization process.