38-Investigation Report (English)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Report of the OAS Electoral Observation Mission in Honduras

Preliminary Report of the OAS Electoral Observation Mission in Honduras The Electoral Observation Mission of the Organization of American States (EOM/OAS) in Honduras, headed by former President of Bolivia Jorge “Tuto” Quiroga, deployed a team of 82 experts and observers from 25 countries to cover the general elections held on November 26. The Mission began by dispatching an advance technical team to the country on October 30 to observe the preparation of the electoral cases (maletas electorales, containing election materials), the training being given to members of the polling stations, and the delivery of their credentials, along with other aspects relating to the transmission and dissemination of results, including demonstrations and the test run drill on November 12. On November 6 that team was joined by the mobile group observers, who traveled to the different departments in the country to observe in situ the progress being made with preparations for the elections and to meet the actors involved in the electoral process. The Mission completed its deployment with the arrival of the experts, regional coordinators, and international observers, together with the Head of Mission and the Special Advisor to the EOM, former President of Guatemala Álvaro Colom. During its stay in Honduras, the Mission met with government and electoral authorities, political parties and coalitions, the Supreme Court of Justice, representatives of civil society, the electricity company (Empresa de Energía de Honduras), and the diplomatic community, as well as other actors. The experts conducted a substantive analysis of the electoral process in terms of its organization, the technology used, campaign financing, gender perspective, electoral justice, and facilities for voting abroad. -

Letter from the Government of Honduras on Actions Taken

Appendix 13 – Letter from the Government of Honduras on actions taken OFFICIAL LETTER No.1077-DGPE/DSM-10 Tegucigalpa, June 4, 2010 Excellency, It is my honor to present my compliments and to say that the purpose of this letter in follow- up to the two notes sent to the international community in April 2010 is to express our desire for genuine understanding of the situation in our country and that the international community be suitably and correctly informed of the efforts of the Government of Honduras to implement a real process of national unity and reconciliation. I should begin by drawing attention to the fact that our president, Mr. Porfirio Lobo Sosa, has set about the task of leading the country with the strength afforded him by the legitimacy of a transparent election extensively observed by the international community, in which the majority of the people of Honduras clearly, lawfully, and unmistakably expressed their will in the search for peace, stability, and restored unity. This electoral process, called by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal under the administration of former President Zelaya Rosales, was preceded by the primary elections in which all legally registered political parties chose their candidates to the National Congress, Municipalities, and the Presidency of the Republic, a process monitored by international observers—including those from the Organization of American States (OAS)—who noted the transparency and success thereof. I am at pains to draw your attention to the fact that Article 51 of the Constitution of Honduras defines the Supreme Electoral Tribunal as an autonomous and independent entity responsible for the convocation, organization, direction, and supervision of electoral processes. -

LIFE and WORK in the BANANA FINCAS of the NORTH COAST of HONDURAS, 1944-1957 a Dissertation

CAMPEÑAS, CAMPEÑOS Y COMPAÑEROS: LIFE AND WORK IN THE BANANA FINCAS OF THE NORTH COAST OF HONDURAS, 1944-1957 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda January 2011 © 2011 Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda CAMPEÑAS Y CAMPEÑOS: LIFE AND WORK IN THE BANANA FINCAS OF THE NORTH COAST OF HONDURAS, 1944-1957 Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda, Ph.D. Cornell University 2011 On May 1st, 1954 banana workers on the North Coast of Honduras brought the regional economy to a standstill in the biggest labor strike ever to influence Honduras, which invigorated the labor movement and reverberated throughout the country. This dissertation examines the experiences of campeños and campeñas, men and women who lived and worked in the banana fincas (plantations) of the Tela Railroad Company, a subsidiary of the United Fruit Company, and the Standard Fruit Company in the period leading up to the strike of 1954. It describes the lives, work, and relationships of agricultural workers in the North Coast during the period, traces the development of the labor movement, and explores the formation of a banana worker identity and culture that influenced labor and politics at the national level. This study focuses on the years 1944-1957, a period of political reform, growing dissent against the Tiburcio Carías Andino dictatorship, and worker agency and resistance against companies' control over workers and the North Coast banana regions dominated by U.S. companies. Actions and organizing among many unheralded banana finca workers consolidated the powerful general strike and brought about national outcomes in its aftermath, including the state's institution of the labor code and Ministry of Labor. -

Leadership and Ethical Development: Balancing Light and Shadow

LEADERSHIP AND ETHICAL DEVELOPMENT: BALANCING LIGHT AND SHADOW Benyamin M. Lichtenstein, Beverly A. Smith, and William R. Torbert A&stract: What makes a leader ethical? This paper critically examines the answer given by developmental theory, which argues that individuals can develop throu^ cumulative stages of ethical orientation and behavior (e.g. Hobbesian, Kantian, Rawlsian), such that leaders at later develop- mental stages (of whom there are empirically very few today) are more ethical. By contrast to a simple progressive model of ethical develop- ment, this paper shows that each developmental stage has both positive (light) and negative (shadow) aspects, which affect the ethical behaviors of leaders at that stage It also explores an unexpected result: later stage leaders can have more significantly negative effects than earlier stage leadership. Introduction hat makes a leader ethical? One answer to this question can be found in Wconstructive-developmental theory, which argues that individuals de- velop through cumulative stages that can be distinguished in terms of their epistemological assumptions, in terms of the behavior associated with each "worldview," and in terms of the ethical orientation of a person at that stage (Alexander et.al., 1990; Kegan, 1982; Kohlberg, 1981; Souvaine, Lahey & Kegan, 1990). Developmental theory has been successfully applied to organiza- tional settings and has illuminated the evolution of managers (Fisher, Merron & Torbert, 1987), leaders (Torbert 1989, 1994b; Fisher & Torbert, 1992), and or- ganizations (Greiner, 1972; Quinn & Cameron, 1983; Torbert, 1987a). Further, Torbert (1991) has shown that successive stages of personal development have an ethical logic that closely parallels the socio-historical development of ethical philosophies during the modern era; that is, each sequential ethical theory from Hobbes to Rousseau to Kant to Rawls explicitly outlines a coherent worldview held implicitly by persons at successively later developmental stages. -

Multilingualism in Cyberspace: Indigenous Languages for Empowerment

REGIONAL CONFERENCE FOR CENTRAL AMERICA CONFERENCE REPORT MULTILINGUALISM IN CYBERSPACE: INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES FOR EMPOWERMENT 27 and 28 November 2015 San José, 2015 – 2 – Published in 2015 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and UNESCO Field Office in San José, Costa Rica © UNESCO 2015 Editor: José Manuel Valverde Rojas Coordinator: Günther Cyranek UNESCO team: Pilar Alvarez-Liso, Director and Representative, UNESCO Cluster Office Central America in San José, Costa Rica Boyan Radoykov, Chief, Section for Universal Access and Preservation, Knowledge Societies Division, Communication and Information Sector, UNESCO Irmgarda Kasinskaite-Buddeberg, Programme specialist, Section for Universal Access and Preservation, Knowledge Societies Division, Communication and Information Sector, UNESCO – 3 – CONTENTS Page PREFACE .............................................................................................................................. 6 SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. 8 1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT OF THE REGIONAL EXPERT CONFERENCE. ......... 10 1.1 OVERVIEW OF THE PARTNERS AND ORGANIZATION OF THE EVENT .......... 12 2. CONCEPT NOTE. .......................................................................................................... 15 2.1 Multilingual information and knowledge are key determinants of wealth creation, social transformation and human -

To Clarify These Terms, Our Discussion Begins with Hydraulic Conductivity Of

Caribbean Area PO BOX 364868 San Juan, PR 00936-4868 787-766-5206 Technology Transfer Technical Note No. 2 Tropical Crops & Forages Nutrient Uptake Purpose The purpose of this technical note is to provide guidance in nutrient uptake values by tropical crops in order to make fertilization recommendations and nutrient management. Discussion Most growing plants absorb nutrients from the soil. Nutrients are eventually distributed through the plant tissues. Nutrients extracted by plants refer to the total amount of a specific nutrient uptake and is the total amount of a particular nutrient needed by a crop to complete its life cycle. It is important to clarify that the nutrient extraction value may include the amount exported out of the field in commercial products such as; fruits, leaves or tubers or any other part of the plant. Nutrient extraction varies with the growth stage, and nutrient concentration potential may vary within the plant parts at different stages. It has been shown that the chemical composition of crops, and within individual components, changes with the nutrient supplies, thus, in a nutrient deficient soil, nutrient concentration in the plant can vary, creating a deficiency or luxury consumption as is the case of Potassium. The nutrient uptake data gathered in this note is a result of an exhaustive literature review, and is intended to inform the user as to what has been documented. It describes nutrient uptake from major crops grown in the Caribbean Area, Hawaii and the Pacific Basin. Because nutrient uptake is crop, cultivar, site and nutrient content specific, unique values cannot be arbitrarily selected for specific crops. -

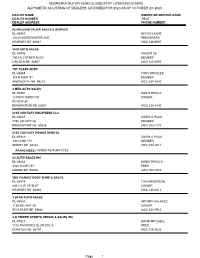

Alphabetical Listing of Dealers Licensed for 2020 As of October 23, 2020

NEBRASKA MOTOR VEHICLE INDUSTRY LICENSING BOARD ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF DEALERS LICENSED FOR 2020 AS OF OCTOBER 23, 2020 DEALER NAME OWNER OR OFFICER NAME DEALER NUMBER TITLE DEALER ADDRESS PHONE NUMBER #2 HAULING TRUCK SALES & SERVICE DL-06965 DEVON LEWIS 10125 SWEETWATER AVE PRES/TREAS KEARNEY NE 68847 (308) 338-9097 14 M AUTO SALES DL-06996 HAIDER ALI 7003 N COTNER BLVD MEMBER LINCOLN NE 68507 (402) 325-8450 1ST CLASS AUTO DL-06388 TONY BUCKLES 358 N MAIN ST MEMBER AINSWORTH NE 69210 (402) 387-2420 2 MEN AUTO SALES DL-05291 DAN R RHILEY 12150 N 153RD CIR OWNER PO BOX 80 BENNINGTON NE 68007 (402) 238-3330 21ST CENTURY EQUIPMENT LLC DL-06065 OWEN A PALM 9738 US HWY 26 MEMBER BRIDGEPORT NE 69336 (308) 262-1110 21ST CENTURY POWER SPORTS DL-05949 OWEN A PALM 1901 LINK 17J MEMBER SIDNEY NE 69162 (308) 254-2511 FRANCHISES: HONDA MOTORCYCLE 24 AUTO SALES INC DL-06268 DANIA PADILLA 3328 S 24TH ST PRES OMAHA NE 68108 (402) 763-1676 2ND CHANCE BODY SHOP & SALES DL-04374 TOM ANDERSON 409 1/2 W 19TH ST OWNER KEARNEY NE 68845 (308) 234-6412 3 STAR AUTO SALES DL-05560 ARTURO VALADEZ 1136 NE HWY 30 OWNER SCHUYLER NE 68661 (402) 352-7912 3-D POWER SPORTS REPAIR & SALES INC DL-07027 DAVID MITCHELL 1108 RIVERSIDE BLVD STE A PRES NORFOLK NE 68701 (402) 316-3633 Page 1 NEBRASKA MOTOR VEHICLE INDUSTRY LICENSING BOARD ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF DEALERS LICENSED FOR 2020 AS OF OCTOBER 23, 2020 DEALER NAME OWNER OR OFFICER NAME DEALER NUMBER TITLE DEALER ADDRESS PHONE NUMBER 308 AUTO SALES DL-06971 STEVE BURNS 908 E 4TH ST OWNER GRAND ISLAND NE 68801 (308) 675-3016 -

Papaya, Mango and Guava Fruit Metabolism During Ripening: Postharvest Changes Affecting Tropical Fruit Nutritional Content and Quality

® Fresh Produce ©2010 Global Science Books Papaya, Mango and Guava Fruit Metabolism during Ripening: Postharvest Changes Affecting Tropical Fruit Nutritional Content and Quality João Paulo Fabi* • Fernanda Helena Gonçalves Peroni • Maria Luiza Passanezi Araújo Gomez Laboratório de Química, Bioquímica e Biologia Molecular de Alimentos, Departamento de Alimentos e Nutrição Experimental, FCF, Universidade de São Paulo, Avenida Lineu Prestes 580, Bloco 14, CEP 05508-900, São Paulo – SP, Brazil Corresponding author : * [email protected] ABSTRACT The ripening process affects the nutritional content and quality of climacteric fruits. During papaya ripening, papayas become more acceptable due to pulp sweetness, redness and softness, with an increment of carotenoids. Mangoes increase the strong aroma, sweetness and vitamin C, -carotene and minerals levels during ripening. Ripe guavas have one of the highest levels of vitamin C and minerals compared to other tropical fleshy fruits. Although during these fleshy fruit ripening an increase in nutritional value and physical-chemical quality is observed, these changes could lead to a reduced shelf-life. In order to minimize postharvest losses, some techniques have been used such as cold storage and 1-MCP treatment. The techniques are far from being standardized, but some interesting results have been achieved for papayas, mangoes and guavas. Therefore, this review focuses on the main changes occurring during ripening of these three tropical fruits that lead to an increment of quality attributes and nutritional -

What's Driving the Attacks?

28 WHAT’S DRIVING THE ATTACKS? CORRUPTION, A LACK OF CONSULTATION, AND A FAILURE TO PROTECT ACTIVISTS Threats and attacks against land and environmental > In Tolupan territory, ex-local mayor for the ruling defenders in Honduras do not occur in a vacuum. Without National Party, Arnaldo Ubina Soto, is currently in jail the widespread corruption currently characterising accused of leading a gang of hitmen involved in government and the natural resource sector, abusive drug-trafficking, murder and money laundering.194 projects could not go ahead so easily, and impunity for those responsible would not flourish. The fact that > Ex-army general Filánder Uclés is currently facing communities are rarely properly informed about projects charges for continually threatening Tolupan community or consulted on the use of their land breeds conflict members to leave their lands.195 which puts activists, and ultimately investments too, at > risk. The Honduran government has completely failed to 64 community members, as well as their leaders, from put in place adequate protection policies and prosecute the Garifuna community of Barra Vieja had charges of the perpetrators of violence, some of whom are ‘illegal squatting’ dismissed by local courts who ruled state actors. in favour of their rights to their ancestral lands. But Honduras is not a failed state and has, on numerous And yet, sadly these examples stand out because they are occasions, demonstrated that it can tackle the issues so unusual. The norm is that corruption means projects outlined in this report, when high-level officials have the that wouldn’t otherwise get approval, get the green light. -

Honduras SIGI 2019 Category Low SIGI Value 2019 22%

Country Honduras SIGI 2019 Category Low SIGI Value 2019 22% Discrimination in the family 25% Legal framework on child marriage 50% Percentage of girls under 18 married 27% Legal framework on household responsibilities 50% Proportion of the population declaring that children will suffer if mothers are working outside home for a pay - Female to male ratio of time spent on unpaid care work 3.1 Legal framework on inheritance 0% Legal framework on divorce 0% Restricted physical integrity 25% Legal framework on violence against women 25% Proportion of the female population justifying domestic violence 12% Prevalence of domestic violence against women (lifetime) 22% Sex ratio at birth (natural =105) 105 Legal framework on reproductive rights 100% Female population with unmet needs for family planning 11% Restricted access to productive and financial resources 24% Legal framework on working rights 100% Proportion of the population declaring this is not acceptable for a woman in their family to work outside home for a pay 7% Share of managers (male) 53% Legal framework on access to non-land assets 0% Share of house owners (male) 69% Legal framework on access to land assets 25% Share of agricultural land holders (male) - Legal framework on access to financial services 25% Share of account holders (male) 54% Restricted civil liberties 15% Legal framework on civil rights 0% Legal framework on freedom of movement 0% Percentage of women in the total number of persons not feeling safe walking alone at night 66% Legal framework on political participation 0% Share of the population that believes men are better political leaders than women - Percentage of male MP’s 79% Legal framework on access to justice 0% Share of women declaring lack of confidence in the justice system 58% Note: Higher values indicate higher inequality. -

Download the Carlisle ELECTRICAL & WIRING TREASURED MOTORCAR SERVICES RED BEARDS TOOLS Events App for Iphone and L 195-198, M 196-199 Android

OFFICIAL EVENT GUIDE Contents WORLD’S FINEST CAR SHOWS & AUTOMOTIVE EVENTS 5 WELCOME 7 FORD MOTOR COMPANY 9 SPECIAL GUESTS 10 EVENT HIGHLIGHTS 15 WOMEN’S OASIS 2019-2020 EVENT SCHEDULE 17 NPD SHOWFIELD HIGHLIGHTS JAN. 18-20, 2019 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAYS: AUTO MANIA 19 FORD GT PROTOTYPE ALLENTOWN PA FAIRGROUNDS JAN. 17-19, 2020 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: FEB. 22-24, 2019 21 FORD NATIONALS SELECT WINTER AUTOFEST LAKELAND SUN ’n FUN, LAKELAND, FL FEB. 21-23, 2020 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: 22 40 YEARS OF THE FOX BODY LAKELAND WINTER FEB. 22-23, 2019 COLLECTOR CAR AUCTION FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: SUN ’n FUN, LAKELAND, FL FEB. 21-22, 2020 25 50 YEARS OF THE MACH 1 APRIL 24-28, 2019 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: SPRING CARLISLE CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS 26 50 YEARS OF THE BOSS APRIL 22-26, 2020 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: SPRING CARLISLE APRIL 25-26, 2019 29 50 YEARS OF THE ELIMINATOR COLLECTOR CAR AUCTION CARLISLE EXPO CENTER APRIL 23-24, 2020 29 SOCIAL STOPS IMPORT & PERFORMANCE MAY 17-19, 2019 EVENT MAP NATIONALS 20 CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS MAY 15-17, 2020 19 EVENT SCHEDULE FORD NATIONALS MAY 31-JUNE 2, 2019 PRESENTED BY MEGUIAR’S 34 GUEST SPOTLIGHT CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS JUNE 5-7, 2020 37 SUMMER OF ’69 CHEVROLET NATIONALS JUNE 21-22, 2019 CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS 39 VENDORS: BY SPECIALTY JUNE 26-27, 2020 CARLISLE AUCTIONS JUNE 22, 2019 43 VENDORS: A-Z SUMMER SALE CARLISLE EXPO CENTER JUNE 27, 2020 48 ABOUT OUR PARTNERS JULY 12-14, 2019 CARLISLE FAIRGROUNDS CHRYSLER NATIONALS 51 POLICIES & INFORMATION CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS JULY 10-12, 2020 53 CONCESSIONS TRUCK NATIONALS AUG. -

Charter Cities

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 27 (2018-2019) Issue 3 Symposium: Rights Protection in Article 6 International Criminal Law and Beyond March 2019 Charter Cities Lan Cao Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the International Law Commons, and the International Trade Law Commons Repository Citation Lan Cao, Charter Cities, 27 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 717 (2019), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmborj/vol27/iss3/6 Copyright c 2019 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj CHARTER CITIES Lan Cao* INTRODUCTION Globalization has produced a mongrelized, hybrid, and heterogeneous reality that transcends national territory. For example, in today’s globalized world, corporate products are frequently globally sourced and produced. “A Pontiac Le Mans, osten- sibly a General Motors product of American nationality, is in fact a globally com- posite product involving South Korean assembly; Japanese engines, transaxles and electronics; German design and style engineering; Taiwanese, Singaporean, and Japanese small components; British advertising and marketing; and Irish and Bar- badian data processing.”1 Is this an American product or not? “Products appear to be made everywhere and also nowhere in particular, as shown on the following com- puter circuit label: ‘Made in one or more of the following countries: Korea, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Mauritius, Thailand, Indonesia, Mexico, Philip- pines. The exact country of origin is unknown.’”2 Even national governance has become more hybridized under the influence of the forces of globalization.3 The domestic autonomy of states must now contend * Professor Cao is the Betty Hutton Williams Professor of International Economic Law at the Fowler School of Law.