Political Contextuality of Martin Mcdonagh's Hangmen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nine Night at the Trafalgar Studios

7 September 2018 FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED FOR THE NATIONAL THEATRE’S PRODUCTION OF NINE NIGHT AT THE TRAFALGAR STUDIOS NINE NIGHT by Natasha Gordon Trafalgar Studios 1 December 2018 – 9 February 2019, Press night 6 December The National Theatre have today announced the full cast for Nine Night, Natasha Gordon’s critically acclaimed play which will transfer from the National Theatre to the Trafalgar Studios on 1 December 2018 (press night 6 December) in a co-production with Trafalgar Theatre Productions. Natasha Gordon will take the role of Lorraine in her debut play, for which she has recently been nominated for the Best Writer Award in The Stage newspaper’s ‘Debut Awards’. She is joined by Oliver Alvin-Wilson (Robert), Michelle Greenidge (Trudy), also nominated in the Stage Awards for Best West End Debut, Hattie Ladbury (Sophie), Rebekah Murrell (Anita) and Cecilia Noble (Aunt Maggie) who return to their celebrated NT roles, and Karl Collins (Uncle Vince) who completes the West End cast. Directed by Roy Alexander Weise (The Mountaintop), Nine Night is a touching and exuberantly funny exploration of the rituals of family. Gloria is gravely sick. When her time comes, the celebration begins; the traditional Jamaican Nine Night Wake. But for Gloria’s children and grandchildren, marking her death with a party that lasts over a week is a test. Nine rum-fuelled nights of music, food, storytelling and laughter – and an endless parade of mourners. The production is designed by Rajha Shakiry, with lighting design by Paule Constable, sound design by George Dennis, movement direction by Shelley Maxwell, company voice work and dialect coaching by Hazel Holder, and the Resident Director is Jade Lewis. -

Association of Clinical Pathologists

The Bulletin of The Royal College of Pathologists Number 163 July 2013 In this issue The Royal College of Pathologists Everything you wanted to know about your new Pathology: the science behind the cure consultant post but were afraid to ask Voice recognition in histopathology: pros and cons Public Engagement Innovation Grant Scheme www.rcpath.org/bulletin Subscribe to the Bulletin of The Royal College of Pathologists The College’s quarterly membership journal, the Bulletin, is the main means of communications between the College and its members, and between the members themselves. It features topical articles on the latest development in pathology, news from the College, as well as key events and information related to pathology. The Bulletin is delivered free of charge to all active College Members, retired Members who choose to receive mailings and Registered Trainees, and is published four times a year, in January, April, July and October. It is also available for our members to download on the College website at www.rcpath.org/bulletin The subscription rate for libraries and non-members is £100 per annum. To subscribe, contact the Publications Department on 020 7451 6730 or [email protected] Sign up today and keep up to date on what goes on in the world of pathology! The Royal College of Pathologists 2 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AF telephone 020 7451 6700 email [email protected] website www.rcpath.org President Dr Archie Prentice Vice Presidents Dr Bernie Croal Dr Suzy Lishman Professor Mike Wells Registrar Dr Rachael -

Leyland Historical Society

LEYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY (Founded 1968) Registered Charity No. 1024919 PRESIDENT Mr. W. E. Waring CHAIR VICE-CHAIR Mr. P. Houghton Mrs. E. F. Shorrock HONORARY SECRETARY HONORARY TREASURER Mr. M. J. Park Mr. E. Almond Tel: (01772) 337258 AIMS To promote an interest in history generally and that of the Leyland area in particular MEETINGS Held on the first Monday of each month (September to July inclusive) at 7.30 pm in The Shield Room, Banqueting Suite, Civic Centre, West Paddock, Leyland SUBSCRIPTIONS Vice Presidents: £10.00 per annum Members: £10.00 per annum School Members: £1.00 per annum Casual Visitors: £3.00 per meeting A MEMBER OF THE LANCASHIRE LOCAL HISTORY FEDERATION THE HISTORIC SOCIETY OF LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE and THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION FOR LOCAL HISTORY Visit the Leyland Historical Society's Web Site at: http//www.leylandhistoricalsociety.co.uk C O N T E N T S Page Title Contributor 4 Editorial Mary Longton 5 Society Affairs Peter Houghton 7 From a Red Letter Day to days with Red Letters Joan Langford 11 Fascinating finds at Haydock Park Edward Almond 15 The Leyland and Farington Mechanics’ Institution Derek Wilkins Joseph Farington: 3rd December 1747 to Joan Langford 19 30th December 1821 ‘We once owned a Brewery’ – W & R Wilkins of Derek Wilkins 26 Longton 34 More wanderings and musings into Memory Lane Sylvia Thompson Railway trip notes – Leyland to Manchester Peter Houghton 38 Piccadilly Can you help with the ‘Industrial Heritage of Editor 52 Leyland’ project? Lailand Chronicle No. 56 Editorial Welcome to the fifty-sixth edition of the Lailand Chronicle. -

A Veritable Revolution: the Court of Criminal Appeal in English

A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS B.A. University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1986 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 © 2012 CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 Cecile Arden Phillips, Candidate for the Masters of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT In a historic speech to the House of Commons on April 17, 1907, British Attorney General, John Lawson Walton, proposed the formation of what was to be the first court of criminal appeal in English history. Such a court had been debated, but ultimately rejected, by successive governments for over half a century. In each debate, members of the judiciary declared that a court for appeals in criminal cases held the potential of destroying the world-respected English judicial system. The 1907 debates were no less contentious, but the newly elected Liberal government saw social reform, including judicial reform, as their highest priority. After much compromise and some of the most overwrought speeches in the history of Parliament, the Court of Criminal Appeal was created in August 1907 and began hearing cases in May 1908. A Veritable Revolution is a social history of the Court’s first fifty years. There is no doubt, that John Walton and the other founders of the Court of Criminal Appeal intended it to provide protection from the miscarriage of justice for English citizens convicted of criminal offenses. -

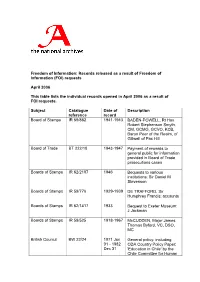

FOI) Requests

Freedom of Information: Records released as a result of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests April 2006 This table lists the individual records opened in April 2006 as a result of FOI requests. Subject Catalogue Date of Description reference record Board of Stamps IR 59/882 1941-1943 BADEN-POWELL, Rt Hon Robert Stephenson Smyth, CM, GCMG, GCVO, KCB, Baron Peer of the Realm, of Gillwell of Pax Hill Board of Trade BT 222/10 1943-1947 Payment of rewards to general public for information provided in Board of Trade prosecutions cases Boards of Stamps IR 62/2197 1946 Bequests to various institutions: Sir Daniel M Stevenson Boards of Stamps IR 59/776 1929-1939 DE TRAFFORD, Sir Humphrey Francis: accounts Boards of Stamps IR 62/1417 1933 Bequest to Exeter Museum: J Jackman Boards of Stamps IR 59/525 1918-1967 McCUDDEN, Major James Thomas Byford, VC, DSO, MC British Council BW 22/24 1971 Jan General policy: including 01 - 1982 ODA Country Policy Paper; Dec 31 'Education in Chile' by the Chile Committee for Human Rights Courts Martial WO 71/1105 1945 Harpley, DA Offence: Rape Courts Martial AIR 18/50 1966 Feb Sgt Kelly, A B. Offence: 21 Murder. (Conviction later quashed) Crime HO 1922 CRIMINAL CASES: 144/1754/425994 ARMSTRONG, Herbert Rowse Convicted at Hereford on 13 April 1922 for murder and sentenced to death Crime HO 144/22540 1926-1946 CRIMINAL: Michael Dennis Corrigan alias Edward Kettering alias Kenneth Edward Cassidy: confidence trickster. Crime HO 144/14913 1931 CRIMINAL: Unsolved murder of Louisa Maud Steele at Blackheath: alleged confession by Arthur James Faraday Salvage, murderer of Ivy Godden. -

An Abstract of the Thesis Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Nicolas Evans for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on June 2, 2017. Title: (Mis)representation & Postcolonial Masculinity: The Origins of Violence in the Plays and Films of Martin McDonagh. Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Neil R. Davison This thesis examines the postmodern confrontation of representation throughout the oeuvre of Martin McDonagh. I particularly look to his later body of work, which directly and self-reflexively confronts issues of artistic representation & masculinity, in order to gain a more nuanced understanding of his earliest and most controversial plays. In part, this thesis addresses misperceptions regarding The Leenane Trilogy, which was initially criticized for the plays’ shows of irreverence and use of caricature and cultural stereotypes. Rather than perpetuating propagandistic or offensive representations, my analysis explores how McDonagh uses affect and genre manipulation in order to parody artistic representation itself. Such a confrontation is meant to highlight the inadequacy of any representation to truly capture “authenticity.” Across his oeuvre, this postmodern proclivity is focused on disrupting the solidification of discourses of hyper-masculinity in the vein of postcolonial, diasporic, and mainstream media’s constructions of masculinity based on aggression and violence. ©Copyright by Nicolas Evans June 2, 2017 All Rights Reserved (Mis)representation & Postcolonial Masculinity: The Origins of Violence in the Plays and Films of Martin McDonagh by Nicolas Evans A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 2, 2017 Commencement June 2017 Master of Arts thesis of Nicolas Evans presented on June 2, 2017 APPROVED: Major Professor, representing English Director of the School of Writing, Literature, and Film Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. -

Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Honors Theses Student Scholarship Fall 2015 Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom Rachel Gaines Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Gaines, Rachel, "Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom" (2015). Honors Theses. 293. https://encompass.eku.edu/honors_theses/293 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i EASTERN KENTUCKY UNIVERSITY Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom Honors Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements of HON 420 Fall 2015 By Rachel Gaines Faculty Mentor Dr. Sucheta Mohanty Department of Government ii Capital Punishment at Home and Abroad: A Comparative Study on the Evolution of the Use of the Death Penalty in the United States and the United Kingdom Rachel Gaines Faculty Mentor Dr. Sucheta Mohanty, Department of Government Abstract: Capital punishment (sometimes referred to as the death penalty) is the carrying out of a legal sentence of death as punishment for crime. The United States Supreme Court has most recently ruled that capital punishment is not unconstitutional. -

The Executioner at War: Soldiers, Spies and Traitors

The Executioner At War: Soldiers, Spies and Traitors lbert Pierrepoint was not called up when war broke out. But there were war-related changes for him as well. Not only murderers and A murderesses could now be punished by death, there were sentences under the Treason Act and Treachery Act as well, both imposing »death« as the maximum penalty. The Treason Act went back to an ancient law of King Edward III's time (1351). »Treason« was, first of all, any attack on the legitimate ruler, for instance by planning to murder him, or on the legitimacy of the succession to the throne: It was treason as well if someone tried to smuggle his genes into the royal family by adultery with the queen, the oldest daughter of the king or the crown prince’s wife. This aspect of the law became surprisingly topical in our days: When it became known that Princess Diana while married to the Prince of Wales had had an affair with her riding instructor James Hewitt, there were quite some law experts who declared this to be a case of treason – following the letter of the Act, it doubtlessly was. However as it would have been difficult to find the two witnesses prescribed by the Act, a prosecution was never started. Just Hewitt’s brother officers of the Household Cavalry did something: They »entered his name on the gate« which was equivalent to drumming him out of the regiment and declaring the barracks off limits for him.317 During World War II, it became important that a person committed treason if they supported the king’s enemies in times of war. -

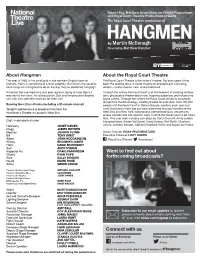

Connect with Us Want to Find out About Forthcoming Broadcasts?

Robert Fox, Matthew Byam Shaw for Playful Productions and Royal Court Theatre Productions present The Royal Court Theatre production of By Martin McDonagh Directed by Matthew Dunster About Hangmen About the Royal Court Theatre The year is 1965. In his small pub in the northern English town of The Royal Court Theatre is the writers’ theatre. For sixty years it has Oldham, Harry is something of a local celebrity. But what’s the second- been the leading force in world theatre for energetically cultivating best hangman in England to do on the day they’ve abolished hanging? writers – undiscovered, new, and established. Amongst the cub reporters and pub regulars dying to hear Harry’s Through the writers the Royal Court is at the forefront of creating restless, reaction to the news, his old assistant Syd and the peculiar Mooney alert, provocative theatre about now, inspiring audiences and influencing lurk with very different motives for their visit. future writers. Through the writers the Royal Court strives to constantly reinvent the theatre ecology, creating theatre for everyone. Over 120,000 Running time: 2 hrs 40 mins (including a 20-minute interval) people visit the Royal Court in Sloane Square, London, each year and Tonight’s performance is broadcast live from the many thousands more see our work elsewhere through transfers to the Wyndham’s Theatre in London’s West End. West End and New York, national and international tours, residencies across London and site-specific work. In 2016 the Royal Court is 60 Years New. This year work includes new plays by Caryl Churchill, Anna Jordan, Cast, in alphabetical order Mongiwekhaya, Alistair McDowall, David Ireland, Stef Smith, Charlene Hennessy JOSEF DAVIES James, Anthony Neilson, Nathaniel Martello-White and Suzan-Lori Parks. -

Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead

ROSENCRANTZ & GUILDENSTERN ARE DEAD TEACHING RESOURCES F E B 2 017–APR 2017 CONTENTS Company 3 Old Vic Education The Old Vic The Cut Creative team 5 London SE1 8NB Characters 7 E [email protected] @oldvictheatre Synopsis 9 © The Old Vic, 2017 All information is correct at the Themes 13 time of going to press, but may be subject to change Timeline: A brief history of Rosencrantz & Guildenstern 15 Teaching resources Are Dead Written by Anne Langford Design Alexander Parsonage & Matt Lane-Dixon Rehearsal room diary by Jason Lawson, Assistant Director 17 Rehearsal and production photography Manuel Harlan An interview with Anna Fleischle, Set and Costume Designer 19 Old Vic New Voices and Loren Elstein, Costume Designer and Associate Set Hannah Fosker Designer Education & Community Manager Liz Bate Education Manager An interview with Daniel Radcliffe and Joshua McGuire 23 Richard Knowles Stage Business Co-ordinator Shakespeare re-purposed: An exploration of the relationship 25 Poppy Walker Old Vic New Voices Intern between Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead and Hamlet Further details of this production Practical Exercises 28 oldvictheatre.com A day in the life of…Michael Peers, Digital Manager 33 Bibliography and further reading 34 The Old Vic Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead teaching resources 2 COMPANY HERMEILIO MIGUEL AQUINO MATTHEW DURKAN Courtier, u/s Polonius/Claudius Alfred, u/s Rosencrantz Theatre: Well (West End); One Night in Miami (Donmar); Theatre: Nell Gwynn (West End); The History Boys (UK Early Doors (Lowry/UK tour); A Midsummer Night’s tour); The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (Sherman Dream (Hive Theatre, Off Broadway); The Tempest Theatre). -

Mount Robson – 1961

238 T h e A l p i n e J o u r n A l 2 0 1 4 for treason at the Old Bailey in late November 1945, pleading guilty to eight counts of high treason and sentenced to death by hanging. He did TED NORRISH this in order to spare his family any more embarrassment, but the papers at Cambridge show how Amery and his younger son Julian tried every way they could to save his life. Despite a psychiatric report by an eminent Mount Robson – 1961 practitioner, Dr Edward Glover, that he was definitely abnormal with a psychopathic disorder and schizoid tendencies, and the intervention of the South African Field Marshall General Jan Smuts, an AC member, who pleaded directly for clemency with the UK Prime Minister Clement Atlee, it was to no avail. Albert Pierrepoint, the public hangman, described John Amery in his autobiography as the bravest man he had to execute. However, germane to this tragedy, considered by Ronald Harwood as significant to John Amery’s story, is that his father had concealed his part- Jewish ancestry. His mother, Elizabeth Leitner, was actually from a family of well-known Jewish scholars. Leo Amery lost his seat in Parliament in the Labour landslide victory in the General Election of 1945, and refused the offer of a peerage. He was however made a Companion of Honour. Leo kept active in climbing circles almost to the end of his life, ignoring the advice of his old Canadian friend, Wheeler, who, quoting Whymper, advised him in a letter that, ‘a man does not climb mountains after his 60th year’. -

Ruth Ellis in the Condemned Cell : Voyeurism and Resistance.', Prison Service Journal., 199

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 30 August 2012 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Unknown Citation for published item: Seal, L. (2012) 'Ruth Ellis in the condemned cell : voyeurism and resistance.', Prison Service journal., 199 . pp. 17-19. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/psj.html Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Ruth Ellis in the Condemned Cell: Voyeurism and Resistance Dr Lizzie Seal is a Lecturer in Criminology at Durham University. Introduction Holloway’s condemned cell. This provided the next phase of the story, in which a young, attractive mother faced When Ruth Ellis became the last woman to be execution for a murder that seemed eminently executed in England and Wales in July 1955, understandable. Particularly compelling was her execution had long been something which took insistence that she did not want to be reprieved and was place in private.