Disinformation Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1 Elementary Logic

Principles of Mathematics (Math 2450) A®Ë@ Õæ Aë áÖ ß @.X.@ 2017-2018 ÈðB@ É®Ë@ Chapter 1 Elementary Logic The study of logic is the study of the principles and methods used in distinguishing valid argu- ments from those that are not valid. The aim of this chapter is to help the student to understand the principles and methods used in each step of a proof. The starting point in logic is the term statement (or proposition) which is used in a technical sense. We introduce a minimal amount of mathematical logic which lies behind the concept of proof. In mathematics and computer science, as well as in many places in everyday life, we face the problem of determining whether something is true or not. Often the decision is easy. If we were to say that 2 + 3 = 4, most people would immediately say that the statement was false. If we were to say 2 + 2 = 4, then undoubtedly the response would be \of course" or \everybody knows that". However, many statements are not so clear. A statement such as \the sum of the first n odd integers is equal to n2" in addition to meeting with a good deal of consternation, might be greeted with a response of \Is that really true?" or \why?" This natural response lies behind one of the most important concepts of mathematics, that of proof. 1.1 Statements and their connectives When we prove theorems in mathematics, we are demonstrating the truth of certain statements. We therefore need to start our discussion of logic with a look at statements, and at how we recognize certain statements as true or false. -

Formal Proof : Understanding, Writing and Evaluating Proofs, February 2010

Formal Proof Understanding, writing and evaluating proofs David Meg´ıas Jimenez´ (coordinador) Robert Clariso´ Viladrosa Amb la col·laboracio´ de M. Antonia` Huertas Sanchez´ PID 00154272 The texts and images contained in this publication are subject –except where indicated to the contrary– to an Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license (BY-NC-ND) v.3.0 Spain by Creative Commons. You may copy, publically distribute and transfer them as long as the author and source are credited (FUOC. Fundacion´ para la Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (Open University of Catalonia Foundation)), neither the work itself nor derived works may be used for commercial gain. The full terms of the license can be viewed at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode © CC-BY-NC-ND • PID 00154272 Formal Proof Table of contents Introduction ................................................... ....... 5 Goals ................................................... ................ 6 1. Defining formal proofs .......................................... 7 2. Anatomy of a formal proof ..................................... 10 3. Tool-supported proofs ........................................... 13 4. Planning formal proofs ......................................... 17 4.1. Identifying the problem . ..... 18 4.2. Reviewing the literature . ....... 18 4.3. Identifying the premises . ..... 19 4.4. Understanding the problem . ... 20 4.5. Formalising the problem . ..... 20 4.6. Selecting a proof strategy . ........ 21 4.7. Developingtheproof ................................ -

Denying the Antecedent - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Denying the antecedent - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Help us provide free content to the world by • LearnLog more in /about create using Wikipediaaccount for research donating today ! • Article Discussion EditDenying this page History the antecedent From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Denying the antecedent is a formal fallacy, committed by reasoning in the form: If P , then Q . Navigation Not P . ● Main Page Therefore, not Q . ● Contents Arguments of this form are invalid (except in the rare cases where such an argument also ● Featured content instantiates some other, valid, form). Informally, this means that arguments of this form do ● Current events ● Random article not give good reason to establish their conclusions, even if their premises are true. Interaction The name denying the ● About Wikipedia antecedent derives from the premise "not P ", which denies the 9, 2008 ● Community portal "if" clause of the conditional premise.Lehman, v. on June ● Recent changes Carver One way into demonstrate archivedthe invalidity of this argument form is with a counterexample with ● Contact Wikipedia Cited true premises06-35176 but an obviously false conclusion. For example: ● Donate to No. If Queen Elizabeth is an American citizen, then she is a human being. Wikipedia ● Help Queen Elizabeth is not an American citizen. Therefore, Queen Elizabeth is not a human being. Search That argument is obviously bad, but arguments of the same form can sometimes seem superficially convincing, as in the following example imagined by Alan Turing in the article "Computing Machinery and Intelligence": “ If each man had a definite set of rules of conduct by which he regulated his life he would be no better than a machine. -

Xxxxxxxxxxxxxmxxxxxxxx

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 297 950 SE 049 425 AUTHOR Kaput, James J. TITLE Information Technology and Mathematics: Opening New Representational Windows. INSTITUTION Educational Technology Center, Cambridge, MA. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. REPORT NO ETC-86-3 PUB DATE Apr 86 NOTE 28p. PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) -- Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cognitive Development; *Cognitive Processes; Cognitive Structures; *Computer Uses in Education; Educational Policy; *Elementary School Mathematics; Elementary Secondary Education; Geometry; *Information Technology; Learning Processes; Mathematics Education; Microcomputers; Problem Solving; Research; *Secondary School Mathematics ABSTRACT Higher order thinking skills are inevitably developed or exercised relative to some discipline. The discipline may be formal or informal, may or may not be represented in a school curriculum, or relate to a wide variety of domains. Moreover, the development or exercise of thinking skills may take place at differing levels of generality. This paper is concerned with how new uses of information technology can profoundly influence the acquisition and application of higher order thinking skills in or near the domain of mathematics. It concentrates on aspects of mathematics that relate to its representational function based on the beliefs that (1) mathematics itself, as a tool of thought and communication, is essentially representational -

![[Gersting 2014] Chapter 2](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5853/gersting-2014-chapter-2-6935853.webp)

[Gersting 2014] Chapter 2

CS 214 Introduction to Discrete Structures Chapter 2 Proofs, Induction, and Number Theory Mikel D. Petty, Ph.D. Center for Modeling, Simulation, and Analysis CS 214 Proofs, Induction, and Number Theory 2.2 Chapter sections and objectives • 2.1 Proof Techniques ▪ Prove conjectures using direct proof, proof by contrapositive, and proof by contradiction • 2.2 Induction ▪ Recognize when a proof by induction is appropriate ▪ Write proofs by induction using either the first or second principle of induction • 2.3 More on Proof of Correctness Not covered • 2.4 Number Theory in CS 214 © 2014 W. H. Freeman and Company © 2014 University of Alabama in Huntsville © 2014 Mikel D. Petty, Ph.D. CS 214 Proofs, Induction, and Number Theory 2.3 Sample problem The nonprofit organization at which you volunteer has received donations of 792 bars of soap and 400 bottles of shampoo. You want to create packages to distribute to homeless shelters such that each package contains the same number of shampoo bottles and each package contains the same number of bars of soap. How many packages can you create? © 2014 W. H. Freeman and Company © 2014 University of Alabama in Huntsville © 2014 Mikel D. Petty, Ph.D. CS 214 Proofs, Induction, and Number Theory 2.4 2.1 Proof Techniques © 2014 W. H. Freeman and Company © 2014 University of Alabama in Huntsville © 2014 Mikel D. Petty, Ph.D. CS 214 Proofs, Induction, and Number Theory 2.5 Arguments and theorems • Formal arguments of Chapter 1 ▪ Form P → Q, where P, Q compound wffs ▪ Objective: show argument is valid ▪ Intrinsically true, based on logical structure - Propositional logic; truth of P implied truth of Q - Predicate logic; P → Q true under all interpretations • Theorems of Chapter 2 ▪ Form P → Q, where P, Q compound wffs ▪ Objective: show conclusion is true ▪ Contextually true, based on domain knowledge - Propositional logic; P true, therefore Q true - Predicate logic; P and P → Q true under specific interpretation ▪ Combine formal logic and domain knowledge ▪ Often stated less formally than formal arguments © 2014 W. -

Teaching and Learning of Proof in the College Curriculum

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2011 Teaching and learning of proof in the college curriculum Maja Derek San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Derek, Maja, "Teaching and learning of proof in the college curriculum" (2011). Master's Theses. 3922. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.ytyx-fs6x https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3922 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING AND LEARNING OF PROOF IN THE COLLEGE CURRICULUM A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Mathematics San Jos´eState University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Maja Derek May 2011 c 2011 Maja Derek ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled TEACHING AND LEARNING OF PROOF IN THE COLLEGE CURRICULUM by Maja Derek APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS SAN JOSE´ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2011 Dr. Joanne Rossi Becker Department of Mathematics Dr. Richard Pfiefer Department of Mathematics Dr. Cheryl Roddick Department of Mathematics ABSTRACT TEACHING AND LEARNING OF PROOF IN THE COLLEGE CURRICULUM by Maja Derek Mathematical proof, as an essential part of mathematics, is as difficult to learn as it is to teach. In this thesis, we provide a short overview of how mathematical proof is understood by students in K-16. -

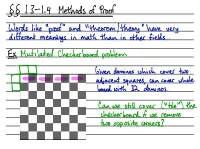

§§ 1.3-1.4 Methods of Proof

§§ 1.3-1.4 Methods of Proof " like " " " Words proof and theorem /theory have very different meanings in math than in other fields . EI Mutilated Checkerboard problem !1! Given dominos which cover two can cover whole adjacent squares , § board with 32 dominos . " " Can we still cover ( tile ) the checkerboard if we remove two opposite corners ? . Scientific Approach After 2 ( . we 5,109200 , 20,000 , ) attempts suspect " " can't be done . Might eventually be called theory . be more accurate But eventually may replaced by explanation . Mathematical Approach We want airtight logical argument . A connect !! mathematical proof is true for all eternity I ) Pf that it can't be done : 1 B Each domino covers lw . , After 30 dominos 2W remain which cannot , , be covered by 1 domino . In symbols to construct a series of , prove p⇒q , . ⇒ . implications , sa 5 : if is Key p true and each implication is tug then true as well ! g .⇒sn⇒qis p⇒s⇒ D. Before we start what can assume in these sections ? , you • arithmetic , algebra • n is if n=2k some k event integer , integer • n is if n= 2kt I some k . odd , integer 0=2 . 0 so 0 is even , • x is rational if ×= , a ,b of integers , bto ( else in 't ) algebra • arithmetic " " Direct Proof of if n is odd then n2 is odd EI , . One approach : start by writing given information out write deft etc . Do same at bottom of rephrase, , fur what want to show . Connect page we by filling in between . : k Let n be odd so n=2kH for some . -

Logical Fallacy Cheat Sheet

Logical Fallacy Cheat Sheet FALLACY NOTES Ad Populum Support is given for some conclusion because it is popular. Also called ‘bandwagon.’ “Everybody agrees that poison Ivy is contagious, so it must be true.” Appeal to Emotion An argument is made due to the manipulation of emotions, rather than the use of valid reasoning. “Illegal immigration makes you angry, vote on that!” Hasty Generalization (Proof by Example) Moving from an existential claim to a universal: I know that something has the property P. There- fore, everything has the property P. “I went against my party once, therefore I am always independent.” Post hoc ergo propter hoc (After this therefore because of this) This fallacy is often used to give a coincidental circumstance the appearance of causation. “Crime went up after marijuana was legalized, therefore crime went up because marijuana was legalized.” Straw Man Arguing against a position which you create spe- cifically to be easy to argue against, rather than the position actually held by those who oppose your point of view. “She wants to teach sex ed to children in the womb!” FALLACY NOTES Ad hominem An argument that attacks the person, rather than addressing the argument itself. Poisoning the well, so to speak. “He’s rich, so his position on how to deal with poverty must be wrong.” Argument from (bad) authority Stating that a claim is true because a person or group of perceived authority says it is true, when that per- son or groups is not really a reliable authority on the topic. “Einstein believes in God. -

Fallacies and Pitfalls of Language 1St Edition Kindle

FALLACIES AND PITFALLS OF LANGUAGE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK S Morris Engel | 9780486157436 | | | | | Fallacies and Pitfalls of Language 1st edition PDF Book Like pattern detection, this is a useful and important human skill, but people tend to overdo it. A quantification fallacy is an error in logic where the quantifiers of the premises are in contradiction to the quantifier of the conclusion. Preview — Fallacies and Pitfalls of Language by S. Cambridge University Press. Informal fallacies — arguments that are logically unsound for lack of well-grounded premises. Sometimes one small twist of circumstance can change the course of our lives. Journal of the History of Ideas. Elementary Turkish Lewis Thomas. Home Contact us Help Free delivery worldwide. We are treated to more and more euphemisms slums are called "substandard housing"; dogcatchers, "animal welfare officers". Clark, Jef; Clark, Theo While there are doubtlessly measurement problems involved in counting the poor, Best's discussion centers on a definition problem, and thus belongs under the previous heading. Lists portal Philosophy portal. Maybe so, but what about craps players? The following fallacies involve inferences whose correctness is not guaranteed by the behavior of those logical connectives, and hence, which are not logically guaranteed to yield true conclusions. We can notify you when this item is back in stock. The following is a sample of books for further reading, selected for a combination of content, ease of access via the internet, and to provide an indication of published sources that interested readers may review. Heads I win, tails you lose. If you're not a statistician, then this book's for you. -

Reasoning Right Effective and Defective Arguments Reasoning Right Part of the Hands-On, Heads-Up Philosophy Series

Introducing the Principles of Inference through Practical Exercises instructor’s edition Reasoning Right Effective and defective arguments Reasoning Right part of the hands-on, heads-up philosophy series — printing 1.2 Table of Contents | Table of Contents 1 Expressions 1 Reasoning 1 using arguments to express inferences Deduction 3 standards for valid deductive arguments Transformation 6 rephrasing into equivalent expressions Induction 8 standards for strong inductive arguments Fallacies 10 formal and informal defective arguments Non-Inference 22 statements not connected by inference 2 Exercise Sessions 30 iv | | Preface 1.1 Going Where? 1.2 Getting There Humanities > Philosophy > Reasoning. Reasoning Right is a exercise book. You—or That’s the typical classifcation. The truth is, a group of you—form the Court of Reason. Each however, that reasoning is an essential vehicle session, you are given a variety of passages. for all disciplines. Well, perhaps language is the (You might fnd a few of your own arguments, vehicle, reasoning is the driver, and the subject at least in the roster of fallacies.) Judge whether matter is riding shotgun. Anyway, without rea- a passage is an argument, a fallacy, or neither soning it is rather diffcult to advocate or object by applying the principles of inference. If you to a claim in any subject, whether politics or wish, start with a passage and go looking for the arts. So what you have here are handouts an inference rule that fts. Conversely, get to for aspiring politicians, art critics, or anyone know the rules of inference to begin with, then interested in the nature of argument and the consider the passages. -

Teaching Discrete Mathematics Entirely from Primary Historical Sources

DISCRETE MATHEMATICS 1 TEACHING DISCRETE MATHEMATICS ENTIRELY FROM PRIMARY HISTORICAL SOURCES Janet Heine Barnett Mathematics and Physics Colorado State University { Pueblo Pueblo, CO 81001, USA [email protected] Guram Bezhanishvili Mathematics New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA [email protected] Jerry Lodder Mathematics New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA [email protected] David Pengelley Mathematics New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA [email protected] 2 J. Barnett, G. Bezhanishvili, J. Lodder and D. Pengelley TEACHING DISCRETE MATHEMATICS ENTIRELY FROM PRIMARY HISTORICAL SOURCES Abstract: We describe teaching an introductory discrete mathematics course entirely from student projects based on primary historical sources. We present case studies of four projects that cover the content of a one-semester course, and mention various other courses that we have taught with primary source projects. Keywords: primary historical sources, original historical sources, peda- gogy, discrete mathematics 1 INTRODUCTION In [7] we described teaching undergraduate mathematics using student projects based on primary historical sources. We presented our moti- vation, our pedagogy, the advantages and challenges of teaching with primary historical sources, student responses, and three sample project case studies. All our projects and how we have used them in various courses may be found in [2, 3, 4, 5, 23]. Our student projects are modular, and can be used to replace even a small part of the textbook material in a course. Among the myriad positive student comments about learning mathematics from primary sources, remarks like the following inspired us to aim higher, for more than just small parts of a course: You don't learn to play an instrument without listening to those who played it best. -

Logic and Computation

Logic and Computation Lecture notes Jeremy Avigad Assistant Professor, Philosophy Carnegie Mellon University Version: January 2002 Preface This document comprises a set of lecture notes that I prepared in the fall of 1998, while teaching a course called Logic and Computation in the Philoso- phy Department at Carnegie Mellon University. I distributed these notes to the class and then followed them almost word for word, in the hopes that doing so would enable students to pay more attention to the contents of the lectures, and free them from the drudgery of transcription. The notes were designed to supplement the textbook rather than to replace it, and so they are more wordy and informal than most textbooks in some places, and less detailed in others. Logic and Computation is cross-listed as an introductory graduate course (80-610) and as an advanced course for undergraduates (80-310). Most students were in the philosophy department, in either the undergraduate major in Logic and Computation, the masters’ program of the same name, or the Ph.D. program in Logic, Computation, and Methodology. There was also a contingency of students from computer science, and a smaller one from mathematics (which maintains its own series of logic courses). With this in mind, I tried to present the course as a rigorous introduction to mathematical logic, which lent some attention to philosophical context and computational relevance, but did not require a good deal of mathematical background. As prerequisites (described in more detail in Chapter 1), I required some familiarity with first-order logic, and some background in reading and writing mathematical proofs.