SSS 39-2-4.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Future-Of-Immortality-Remaking-Life

The Future of Immortality Princeton Studies in Culture and Technology Tom Boellstorff and Bill Maurer, Series Editors This series presents innovative work that extends classic ethnographic methods and questions into areas of pressing interest in technology and economics. It explores the varied ways new technologies combine with older technologies and cultural understandings to shape novel forms of subjectivity, embodiment, knowledge, place, and community. By doing so, the series demonstrates the relevance of anthropological inquiry to emerging forms of digital culture in the broadest sense. Sounding the Limits of Life: Essays in the Anthropology of Biology and Beyond by Stefan Helmreich with contributions from Sophia Roosth and Michele Friedner Digital Keywords: A Vocabulary of Information Society and Culture edited by Benjamin Peters Democracy’s Infrastructure: Techno- Politics and Protest after Apartheid by Antina von Schnitzler Everyday Sectarianism in Urban Lebanon: Infrastructures, Public Services, and Power by Joanne Randa Nucho Disruptive Fixation: School Reform and the Pitfalls of Techno- Idealism by Christo Sims Biomedical Odysseys: Fetal Cell Experiments from Cyberspace to China by Priscilla Song Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming by T. L. Taylor Chasing Innovation: Making Entrepreneurial Citizens in Modern India by Lilly Irani The Future of Immortality: Remaking Life and Death in Contemporary Russia by Anya Bernstein The Future of Immortality Remaking Life and Death in Contemporary Russia Anya Bernstein -

From Logos to Bios: Hellenic Philosophy and Evolutionary Biology

From Logos to Bios: Hellenic Philosophy and Evolutionary Biology by Wynand Albertus de Beer submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of D Litt et Phil in the subject Religious Studies at the University of South Africa Supervisor: Prof Danie Goosen February 2015 Dedicated with grateful acknowledgements to my supervisor, Professor Danie Goosen, for his wise and patient guidance and encouragement throughout my doctoral research, and to the examiners of my thesis for their helpful comments and suggestions. From Logos to Bios: Hellenic Philosophy and Evolutionary Biology by W.A. de Beer Degree: D Litt et Phil Subject: Religious Studies Supervisor: Prof Danie Goosen Summary: This thesis deals with the relation of Hellenic philosophy to evolutionary biology. The first part entails an explication of Hellenic cosmology and metaphysics in its traditional understanding, as the Western component of classical Indo-European philosophy. It includes an overview of the relevant contributions by the Presocratics, Plato, Aristotle, and the Neoplatonists, focussing on the structure and origin of both the intelligible and sensible worlds. Salient aspects thereof are the movement from the transcendent Principle into the realm of Manifestation by means of the interaction between Essence and Substance; the role of the Logos, being the equivalent of Plato’s Demiurge and Aristotle’s Prime Mover, in the cosmogonic process; the interaction between Intellect and Necessity in the formation of the cosmos; the various kinds of causality contributing to the establishment of physical reality; and the priority of being over becoming, which in the case of living organisms entails the primacy of soul over body. -

The Making of Ethnicity in Southern Bessarabia: Tracing the Histories Of

The Making of Ethnicity in Southern Bessarabia: Tracing the histories of an ambiguous concept in a contested land Dissertation Zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakultät I Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, von Herrn Simon Schlegel geb. am 23. April 1983 in Rorschach (Schweiz) Datum der Verteidigung 26. Mai 2016 Gutachter: PD Dr. phil. habil. Dittmar Schorkowitz, Dr. Deema Kaneff, Prof. Dr. Gabriela Lehmann-Carli Contents Deutsche Zusammenfassung ...................................................................................................................................... iii 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Questions and hypotheses ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.2. History and anthropology, some methodological implications ................................................. 6 1.3. Locating the field site and choosing a name for it ........................................................................ 11 1.4. A brief historical outline .......................................................................................................................... 17 1.5. Ethnicity, natsional’nost’, and nationality: definitions and translations ............................ -

Between Holy Russia and a Monkey: Darwin's Russian Literary and Philosophical Critics

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Summer 2019 Between Holy Russia and a Monkey: Darwin's Russian Literary and Philosophical Critics Brendan G. Mooney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mooney, B. G.(2019). Between Holy Russia and a Monkey: Darwin's Russian Literary and Philosophical Critics. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5484 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BETWEEN HOLY RUSSIA AND A MONKEY: DARWIN’S RUSSIAN LITERARY AND PHILOSOPHICAL CRITICS by Brendan G. Mooney Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2012 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2015 Master of Arts Middlebury College, 2018 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Judith Kalb, Major Professor Alexander Ogden, Committee Member James Barilla, Committee Member Jeffrey Dudycha, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Brendan G. Mooney, 2019 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To the women who made this dissertation possible: Judith Kalb, Alice Geary, Lynne Geary, Alice Clemente, Megan Stark, Katherine Mark, Marilyn Dwyer, and, finally, Shannon, Eleanor, and Caroline Mooney. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project began, little did I know, after reading Lev Tolstoy’s 1889 novella The Kreutzer Sonata. -

Soviet Geographers and the Great Patriotic War, 1941E1945: Lev Berg and Andrei Grigor’Ev

Journal of Historical Geography xxx (2014) 1e10 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Historical Geography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhg Feature: European Geographers and World War II Soviet geographers and the Great Patriotic War, 1941e1945: Lev Berg and Andrei Grigor’ev Denis J.B. Shaw* and Jonathan D. Oldfield School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, UK Abstract The significance of the Second World War for Soviet geography was somewhat different from that in much of the West. In the USSR, as a result of the 1917 Russian Revolution and, more particularly, of Joseph Stalin’s ‘Great Turn’ implemented in 1929e1933, geographers were faced with pronounced political and economic challenges of a kind which arguably only confronted most Western geographers with the onset of war. It is therefore impossible to un- derstand the impact of the war for Soviet geography without taking into account this broader context, including events during the turbulent post-war years. The paper will focus on the experiences of two prominent geographers who played a major role in the developments of the era including their responses to the revolutionary circumstances occurring from the late 1920s, their activities and experiences during the war, and the debates and conflicts they engaged in during the post-war crisis. Some of the more significant contrasts with geographical developments in Western countries during these years will be emphasized. Ó 2014 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). Keywords: Soviet geography; Andrei Grigor’ev; Lev Berg; USSR Academy of Sciences Institute of Geography; Stalin era Towards the end of January, 1947, just three years after the lifting of geographers, especially those working in the Office of Strategic the German blockade of the city by Soviet forces, some 600 or so Services (OSS) in Washington DC. -

TOWARDS a SEMIOTIC BIOLOGY Life Is the Action of Signs

• TOWARDS [ ASEMIOTIC ' BIOLOGY Life is the Action of Signs Imperial College Press TOWARDS A SEMIOTIC BIOLOGY Life is the Action of Signs P771tp.indd 1 5/3/11 5:22 PM TOWARDS A SEMIOTIC BIOLOGY Life is the Action of Signs Sense world s si interpretant io m e s Receptor Sense net Carrier of a feature sign Internal world Object Opposite structure Effect net Carrier of an effect representamen object Effector Effect world Editors Claus Emmeche University of Copenhagen, Denmark Kalevi Kull University of Tartu, Estonia Imperial College Press ICP P771tp.indd 2 5/3/11 5:22 PM This page is intentionally left blank Published by Imperial College Press 57 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9HE Distributed by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. 5 Toh Tuck Link, Singapore 596224 USA office: 27 Warren Street, Suite 401-402, Hackensack, NJ 07601 UK office: 57 Shelton Street, Covent Garden, London WC2H 9HE British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. TOWARDS A SEMIOTIC BIOLOGY Life is the Action of Signs Copyright © 2011 by Imperial College Press All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission from the Publisher. For photocopying of material in this volume, please pay a copying fee through the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. In this case permission to photocopy is not required from the publisher. -

Empty Spaces Perspectives on Emptiness in Modern History

IHR Conference Series Empty Spaces Perspectives on emptiness in modern history Edited by Courtney J. Campbell, Allegra Giovine and Jennifer Keating Empty Spaces perspectives on emptiness in modern history Empty Spaces perspectives on emptiness in modern history Edited by Courtney J. Campbell, Allegra Giovine and Jennifer Keating UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First published in 2019 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU Text © contributors, 2019 Images © contributors and copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as authors of this work. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. If you would like to re-use any third-party material not covered by the book’s Creative Commons license, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org or to purchase at https://www.sas.ac.uk/publications ISBN 978-1-909646-49-0 (hardback edition) 978-1-909646-52-0 (PDF edition) 978-1-909646-50-6 (.epub edition) 978-1-909646-51-3 (.mobi edition) DOI 10.14296/919.9781909646520 Contents Acknowledgements vii List of figures ix Notes on contributors xiii Introduction: Confronting emptiness in history 1 Courtney J. -

The Theory of Evolution

The Theory of Evolution The Theory of Evolution: From a Space Vacuum to Neural Ensembles and Moving Forward By Oleg Bazaluk The Theory of Evolution: From a Space Vacuum to Neural Ensembles and Moving Forward By Oleg Bazaluk Translated by Tamara Blazhevych Proofread by Lloyd Barton This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Oleg Bazaluk All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8721-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8721-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................ ix Part I: Historical and Philosophical Analysis of the Evolutionary Theories Chapter One ................................................................................................. 3 The Concept of Evolution Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 11 The Concept of Evolution in the Modern Scientific Theories Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Soviet Geographers and the Great Patriotic War, 1941-1945

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Journal of Historical Geography 47 (2015) 40e49 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Historical Geography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhg Feature: European Geographers and World War II Soviet geographers and the Great Patriotic War, 1941e1945: Lev Berg and Andrei Grigor’ev Denis J.B. Shaw* and Jonathan D. Oldfield School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, UK Abstract The significance of the Second World War for Soviet geography was somewhat different from that in much of the West. In the USSR, as a result of the 1917 Russian Revolution and, more particularly, of Joseph Stalin’s ‘Great Turn’ implemented in 1929e1933, geographers were faced with pronounced political and economic challenges of a kind which arguably only confronted most Western geographers with the onset of war. It is therefore impossible to un- derstand the impact of the war for Soviet geography without taking into account this broader context, including events during the turbulent post-war years. The paper will focus on the experiences of two prominent geographers who played a major role in the developments of the era including their responses to the revolutionary circumstances occurring from the late 1920s, their activities and experiences during the war, and the debates and conflicts they engaged in during the post-war crisis. Some of the more significant contrasts with geographical developments in Western countries during these years will be emphasized. Ó 2014 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. -

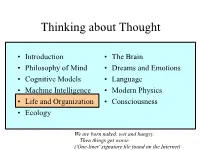

Thinking About Thought

Thinking about Thought • Introduction • The Brain • Philosophy of Mind • Dreams and Emotions • Cognitive Models • Language • Machine Intelligence • Modern Physics • Life and Organization • Consciousness • Ecology We are born naked, wet and hungry. Then things get worse. ('One-liner' signature file found on the Internet) Session Four: Life and Organization for Piero Scaruffi's class "Thinking about Thought" at UC Berkeley (2014) • Roughly These Chapters of My Book “Nature of Consciousness”: – 12. The Evolution Of Life: Of Designers And Designs – 13. The Physics Of Life How will extraterrestrial life look like? How will we recognize it as “life”? Christian Nyby: The Thing From Another World (1951) Edgar Ulmer: The Man from Planet X (1951) Jack Arnold: It Came From Outer Space (1953) Steven Spielberg: Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) Steven Spielberg: E.T. (1982) Tim Burton: Mars Attacks (1996) The Fermi Paradox • Given the probability of exoplanets, the probability of life, the probability of sentient beings, the probability of high technology, etc, the Earth must have been visited many times by aliens • "Where is everybody?" (Enrico Fermi, 1950) • Giuseppe Cocconi and Philip Morrison: "Searching for Interstellar Communications“ (Nature, 1959) • First Search for ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence (SETI) meeting (West Virginia, 1961) • Frank Drake’s equation (1961): number of civilizations in our galaxy with which radio- communication shouldbe possible Unknown: Life on Earth • Carbon A carbon atom has four electrons that can combine -

ESHS 2018 Outline

FRIDAY 14 SEPTEMBER, 12.00-20.00 12.00-14.30 ESHS COUNCIL MEETING IoE - Room 709a 14.00-20.00 REGISTRATION Institute of Education - Level 3, Bedford Way entrance Registration will remain open at the Institute of Education 09.00-18.00 Saturday and Sunday, and at the Science Museum 09.00-18.00 Saturday and Sunday and 09.00-11.00 Monday 15.30-16.00 CONFERENCE WELCOME IoE - Logan Hall ESHS President: Dr Antoni Malet BSHS Vice-President: Dr Patricia Fara UCL STS HoD: Professor Joe Cain 16.00-17.00 NEUENSCHWANDER PRIZE LECTURE IoE - Logan Hall Chair: Professor Dr Erwin Neuenschwander Professor Robert Fox (University of Oxford) Memory, Celebrity, Diplomacy. The Marcellin Bertholet Centenary, 1927 17.00-17.30 AFTERNOON TEA 17.30-18.15 YOUNG SCHOLAR LECTURE 1 IoE - Logan Hall Chair: Dr Patricia Fara Dr Antonio Sánchez (Autonomous University of Madrid) Artisanal Cultures and Practical Knowledge in the Early Modern Iberian World 18-15-19.00 YOUNG SCHOLAR LECTURE 2 IoE - Logan Hall Chair: Professor Ana Simões Professor Stephanie A. Dick (University of Pennsylvania) Making up Minds: Mathematics, Computing, and Automation in the Postwar World 19.00-19.15 WELCOME ON BEHALF OF THE BSHS & SCIENCE MUSEUM /CENTAURUS IoE - Logan Hall BSHS President: Dr Timothy Boon Centaurus Editor: Dr Koen Vermeir 19.15-20.00 WELCOME RECEPTION Institute of Education 1 SATURDAY 15 SEPTEMBER, 09.00-10.30 S07 EXPEDITIONS AND IMAGINARIES IN THE RUSSIAN/SOVIET BORDERLANDS Location: IoE – Room 802 Chair: Lajus, Julia Organiser(s): Jones, Susan D. Feklova, Tatiana (Russian Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg) Cross the line: the expeditions and the borders. -

Translation As a Factor of Social Teleonomy La Traduction Comme Facteur De Téléonomie Sociale Sergey Tyulenev

Document generated on 10/02/2021 1:33 a.m. TTR Traduction, terminologie, rédaction Translation as a Factor of Social Teleonomy La traduction comme facteur de téléonomie sociale Sergey Tyulenev Du système en traduction : approches critiques Article abstract On Systems in Translation: Critical Approaches This article considers translation as a factor in the genesis of social Volume 24, Number 1, 1er semestre 2011 macro-formations—ethnoses and superethnoses. The research combines Niklas Luhmann’s social systems theory, Lem Gumilev’s theory of ethnogenesis URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013253ar and the concept of teleonomy borrowed from evolutionary biologist Ernst DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1013253ar Mayr in order to demonstrate the ethnogenetic function of translation. An ethnos is a closed loose system; it has a life cycle which is teleonomic by nature. Ethnoses evolve by passing through different stages—from inception to See table of contents consummation at the acmetic phase and finally into the post-acmetic succession of phases leading to disintegration. At each of these different stages, the social system requires inputs of varying intensity from the environment. Publisher(s) Translation as a boundary phenomenon serves as a mechanism to ensure such inputs. From the standpoint of its social function, translation is theorized in a Association canadienne de traductologie broader sense than usual—as mediation on intrapersonal, interpersonal, interethnic and intergenerational levels. ISSN 0835-8443 (print) 1708-2188 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Tyulenev, S. (2011). Translation as a Factor of Social Teleonomy. TTR, 24(1), 17–44. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013253ar Tous droits réservés © Sergey Tyulenev, 2012 This document is protected by copyright law.