Recounting the Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborative Storytelling 2.0: a Framework for Studying Forum-Based Role-Playing Games

COLLABORATIVE STORYTELLING 2.0: A FRAMEWORK FOR STUDYING FORUM-BASED ROLE-PLAYING GAMES Csenge Virág Zalka A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 Committee: Kristine Blair, Committee Co-Chair Lisa M. Gruenhagen Graduate Faculty Representative Radhika Gajjala, Committee Co-Chair Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair and Radhika Gajjala, Committee Co-Chairs Forum-based role-playing games are a rich, yet barely researched subset of text- based digital gaming. They are a form of storytelling where narratives are created through acts of play by multiple people in an online space, combining collaboration and improvisation. This dissertation acts as a pilot study for exploring these games in their full complexity at the intersection of play, narrative, and fandom. Building on theories of interactivity, digital storytelling, and fan fiction studies, it highlights forum games’ most unique features, and proves that they are is in no way liminal or secondary to more popular forms of role-playing. The research is based on data drawn from a large sample of forums of various genres. One hundred sites were explored through close textual analysis in order to outline their most common features. The second phase of the project consisted of nine months of participant observation on select forums, in order to gain a better understanding of how their rules and practices influence the emergent narratives. Participants from various sites contributed their own interpretations of forum gaming through a series of ethnographic interviews. This did not only allow agency to the observed communities to voice their thoughts and explain their practices, but also spoke directly to the key research question of why people are drawn to forum gaming. -

Roll 2D6 to Kill

1 Roll 2d6 to kill Neoliberal design and its affect in traditional and digital role-playing games Ruben Ferdinand Brunings August 15th, 2017 Table of contents 2 Introduction: Why we play 3. Part 1 – The history and neoliberalism of play & table-top role-playing games 4. Rules and fiction: play, interplay, and interstice 5. Heroes at play: Quantification, power fantasies, and individualism 7. From wargame to warrior: The transformation of violence as play 9. Risky play: chance, the entrepreneurial self, and empowerment 13. It’s ‘just’ a game: interactive fiction and the plausible deniability of play 16. Changing the rules, changing the game, changing the player 18. Part 2 – Technics of the digital game: hubristic design and industry reaction 21. Traditional vs. digital: a collaborative imagination and a tangible real 21. Camera, action: The digitalisation of the self and the representation of bodies 23. The silent protagonist: Narrative hubris and affective severing in Drakengard 25. Drakengard 3: The spectacle of violence and player helplessness 29. Conclusion: Games, conventionality, and the affective power of un-reward 32. References 36. Bibliography 38. Introduction: Why we play 3 The approach of violence or taboo in game design is a discussion that has historically been a controversial one. The Columbine shooting caused a moral panic for violent shooter video games1, the 2007 game Mass Effect made FOX News headlines for featuring scenes of partial nudity2, and the FBI kept tabs on Dungeons & Dragons hobbyists for being potential threats after the Unabomber attacks.3 The question ‘Do video games make people violent?’ does not occur within this thesis. -

I Never Took Myself Seriously As a Writer Until I Studied at Macquarie.” LIANE MORIARTY MACQUARIE GRADUATE and BEST-SELLING AUTHOR

2 swf.org.au RESEARCH & ENGAGEMENT 1817 - 2017 luxury property sales and rentals THE UN OF ITE L D A S R T E A T N E E S G O E F T A A M L E U R S I N C O A ●C ● SYDNEY THE LIFTED BROW Welcome 3 SWF 2017 swf.org.au A Message from the Artistic Director Contents eading can be a mixed blessing. For In a special event, writer and photographer 4-15 anyone who has had the misfortune Bill Hayes talks to Slate’s Stephen Metcalf about City & Walsh Bay to glance at the headlines recently, Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me, an the last few months have felt like a intimate love letter to New York and his late Guest Curators 4 long fever dream, for reasons that partner, beloved writer and neurologist extend far beyond the outcome of the Oliver Sacks. R Bernadette Brennan has delved into 7 US Presidential election or Brexit. Nights at Walsh Bay More than 20 million refugees are on the move the career of one of Australia’s most adept and another 40 million people are displaced in and admired authors, Helen Garner, with Thinking Globally 11 their own countries, in the largest worldwide A Writing Life. An all-star cast of Garner humanitarian crisis since 1945. admirers – Annabel Crabb, Benjamin Law Scientists announced that the Earth reached and Fiona McFarlane – will join Bernadette City & Walsh Bay its highest temperatures in 2016 – for the third in conversation with Rebecca Giggs about year in a row. -

The Rise of Twitter Fiction…………………………………………………………1

Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Hyman Twitter fiction, an example of twenty-first century digital narrative, allows authors to experiment with literary form, production, and dissemination as they engage readers through a communal network. Twitter offers creative space for both professionals and amateurs to publish fiction digitally, enabling greater collaboration among authors and readers. Examining Jennifer Egan’s “Black Box” and selected Twitter stories from Junot Diaz, Teju Cole, and Elliott Holt, this thesis establishes two distinct types of Twitter fiction—one produced for the medium and one produced through it—to consider how Twitter’s present feed and character limit fosters a uniquely interactive reading experience. As the conversational medium calls for present engagement with the text and with the author, Twitter promotes newly elastic relationships between author and reader that renegotiate the former boundaries between professionals and amateurs. This thesis thus considers how works of Twitter fiction transform the traditional author function and pose new questions regarding digital narrative’s modes of existence, circulation, and appropriation. As digital narrative makes its way onto democratic forums, a shifted author function leaves us wondering what it means to be an author in the digital age. Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Anne Hyman Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Anne Hyman An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of English at Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major April 18, 2016 Thesis Adviser: Vera Kutzinski Date Second Reader: Haerin Shin Date Program Director: Teresa Goddu Date For My Parents Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge Professor Teresa Goddu for shaping me into the writer I have become. -

Intellectual Property and Gender Implications in Online Games

ARTICLES PRETENDING WITHOUT A LICENSE: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND GENDER IMPLICATIONS IN ONLINE GAMES CASEY FIESLER+ I.Introduction............................. .................. 1 II.Pretending and Storytelling in Borrowed Worlds ....... .......... 4 A. Role Playing in the Sand............................ 7 B. Women in the Sandbox ..................... 10 C. Building Virtual Sandcastles............... .......... 13 III.Pretending Without a License ....................... 19 A. Fanwork and Copyright ............ .. ............. 19 B. The Problem with Play........................... 25 C. Paper Doll Princesses and Virtual Castles.................... 26 IV.The Future of Pretending ................................ 31 A. Virtual Paper Dolls .................................... 31 B. Virtual Sandboxes .......................... 32 V.Conclusion .............................................. 33 "It beats playing with regular Barbies."' I. INTRODUCTION According to media accounts, it is only in the past decade or so that video-game designers begun to appreciate the growing female gamer demographic.2 Though the common strategy for targeting these consumers I PhD Candidate, Human-Centered Computing, Georgia Institute of Technology. JD, Vanderbilt University Law School, 2009. An early draft of this article was presented at the 2009 IP/Gender Symposium at American Law School; the author wishes to thank the participants for their valuable input, as well as Professor Steven Hetcher of Vanderbilt Law School. ' A statement by 9-year-old Presleigh, who would rather play with dolls on a website called Cartoon Doll Emporium. Matt Richtel & Brad Stone, Logging On, Playing Dolls, N.Y. TIMES, June 6, 2007, at Cl. 2 E.g., Tina Arons, Gamer Girls: More females flocking to video games, DAILY I 2 BUFFALO INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAWJOURNAL Vol. IX seems to be to make pink consoles and games about fashion design,' there is a growing recognition of trends that indicate gender differences in gaming style. -

The Legend of Henry Paris

When a writer The goes in search of Legend the great of auteur of the golden age of porn, she gets more than she bargained for Henry paris BY TONI BENTLEY Photography by Marius Bugge 108 109 What’s next? The fourth title that kept showing up on best-of lists of the golden age was The Opening of Misty Beethoven by Henry Paris. Who? Searching my favorite porn site, Amazon.com, I found that this 1975 film was just rereleased in 2012 on DVD with all the bells and whistles of a Criterion Collection Citizen Kane reissue: two discs (re- mastered, digitized, uncut, high- definition transfer) that include AAs a professional ballerina, I barely director’s commentary, outtakes, finished high school, so my sense of intakes, original trailer, taglines inadequacy in all subjects but classi- and a 45-minute documentary cal ballet remains adequately high. on the making of the film; plus a In the years since I became a writer, magnet, flyers, postcards and a my curiosity has roamed from clas- 60-page booklet of liner notes. sic literature to sexual literature to classic sexual literature. When Misty arrived in my mailbox days later, I placed the disc A few months ago, I decided to take a much-needed break in my DVD player with considerable skepticism, but a girl has to from toiling over my never-to-be-finished study of Proust, pursue her education despite risks. I pressed play. Revelation. Tolstoy and Elmore Leonard to bone up on one of our most interesting cultural phenomena: pornography. -

Appendix 1: Selected Films

Appendix 1: Selected Films The very random selection of films in this appendix may appear to be arbitrary, but it is an attempt to suggest, from a varied collection of titles not otherwise fully covered in this volume, that approaches to the treatment of sex in the cinema can represent a broad church indeed. Not all the films listed below are accomplished – and some are frankly maladroit – but they all have areas of interest in the ways in which they utilise some form of erotic expression. Barbarella (1968, directed by Roger Vadim) This French/Italian adaptation of the witty and transgressive science fiction comic strip embraces its own trash ethos with gusto, and creates an eccentric, utterly arti- ficial world for its foolhardy female astronaut, who Jane Fonda plays as basically a female Candide in space. The film is full of off- kilter sexuality, such as the evil Black Queen played by Anita Pallenberg as a predatory lesbian, while the opening scene features a space- suited figure stripping in zero gravity under the credits to reveal a naked Jane Fonda. Her peekaboo outfits in the film are cleverly designed, but belong firmly to the actress’s pre- feminist persona – although it might be argued that Barbarella herself, rather than being the sexual plaything for men one might imagine, in fact uses men to grant herself sexual gratification. The Blood Rose/La Rose Écorchée (aka Ravaged, 1970, directed by Claude Mulot) The delirious The Blood Rose was trumpeted as ‘The First Sex Horror Film Ever Made’. In its uncut European version, Claude Mulot’s film begins very much like an arthouse movie of the kind made by such directors as Alain Resnais: unortho- dox editing and tricks with time and the film’s chronology are used to destabilise the viewer. -

07-Philology.Pdf

ACADEMIC STUDIES IN PHILOLOGY İmtiyaz Sahibi / Publisher • Gece Kitaplığı Genel Yayın Yönetmeni / Editor in Chief • Doç. Dr. Atilla ATİK Proje Koordinatörü / Project Coordinator • B. Pelin TEMANA Editör / Editors • Doç. Dr. Fatma Öztürk DAĞABAKAN Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Hakan AKCA Kapak & İç Tasarım / Cover & Interior Design • Gece Akademi Sosyal Medya / Social Media • Arzu ÇUHACIOĞLU Birinci Basım / First Edition • © EKİM 2018 ISBN • 978-605-288-618-2 © copyright Bu kitabın yayın hakkı Gece Kitaplığı’na aittir. Kaynak gösterilmeden alıntı yapılamaz, izin almadan hiçbir yolla çoğaltılamaz. The right to publish this book belongs to Gece Kitaplığı. Citation can not be shown without the source, reproduced in any way without permission. Gece Kitaplığı / Gece Publishing ABD Adres/ USA Address: 387 Park Avenue South, 5th Floor, New York, 10016, USA Telefon / Phone: +1 347 355 10 70 Türkiye Adres / Turkey Address: Kızılay Mah. Fevzi Çakmak 1. Sokak Ümit Apt. No: 22/A Çankaya / Ankara / TR Telefon / Phone: +90 312 384 80 40 +90 555 888 24 26 web: www.gecekitapligi.com e-mail: [email protected] Baskı & Cilt / Printing & Volume Sertifika / Certificate No: 26649 ACADEMIC STUDIES IN PHILOLOGY CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 IS SWIMMING HOME POSSIBLE? ESCAPISM AND UNMASKING OF ARTIFICIAL LIVES IN DEBORAH LEVY’S SWIMMING HOME Kubilay GEÇİKLİ ............................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER 2 TRADITIONAL CHILDREN’S GAMES:KÜTAHYA EXAMPLE Münire BAYSAN ..........................................................................................................................27 -

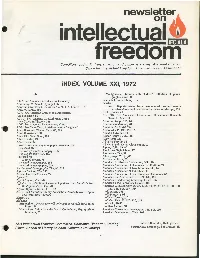

Newsletter on Intellectual ,.U Freedom1 Co-Editors: Judith F

newsletter on intellectual ,.u freedom1 Co-editors: Judith F. Krug, Director, and James A. Harvey, Assistant Director, Office for Intellectual Freedom, American Library Association INDEX, VOLUME XXI, 1972 A Montgomery: Library sells "hidden" collection of porno graphic books, 16 ABC. See American Broadcasting Company Alameda County Library, 114 Abernathy, William H. (Judge),47 Alaska Abortion information, 15, 23, 65, 77, 78, 114, 119, 157, 167 Juneau: Reporter barred from unannounced meeting because Abshire, Bobby, 109 he refused to accept conditions for review of his copy, 108 ACA. See American Correctional Association Albini, James, 21 Ace Bookstore, 20 ALERTS. See Associated Library and Educational Research ACLU. See American Civil Liberties Union Team for Survival Acme Drive-In Theater, 158 Alfred A. Knopf, 115, 140 ADF. See American Documentary Films Alice in Wonder land, 46 ADL. See B'nai B'rith, Anti-Defamation League of Aliens in Our Midst, The, 10 Adult Book and Cinema Shop, 85, 163 Allain, Alex P., 126, 138, 141 Adult Bookstore, 168 Allende, Salvador, 62 Adult City News Shop, 109 Allen, George E., Sr., 116 Adult Theater, 42 Alley, John, 118 Advertisements All in the Family, 14 cause protest among newspaper pressmen, 129 AllYou Should Know About Drugs, 17 censored, 27 Alpert, Hollis, 79, 80 refused by student newspaper, 47 Alta Lorna High School, 97 refused for television, 129 Alternative, The, 91 refused for Alton, Joseph W., Jr., 60 X-rated movies, 76 Alvermann, Hans, 26 rejected by newspaper, 128 American Arbitration Association, -

A Background to Balm in Gilead

A Background to Balm in Gilead: A little bit of information to give you a deeper look at the time, place, and themes in the play 1 | Page Table of Contents Lanford Wilson ............................................................................... Page 3 Balm in Gilead ................................................................................ Page 6 Book of Jeremiah ........................................................................... Page 7 1960s ............................................................................................... Page 9 History of New York City (1946–1977) ........................................ Page 30 Classic ‘New York’: The 1960s .................................................... Page 35 Important Events of the 1960s .................................................... Page 37 Heroin ............................................................................................ Page 46 2 | Page Lanford Wilson (1937- ) American playwright. The following entry provides an overview of Wilson's career through 2003. For further information on his life and works, see CLC, Volumes 7, 14, and 36. INTRODUCTION A prolific writer of experimental and traditional drama, Wilson launched his career at the avant-garde Caffe Cino during the off-off-Broadway movement of the 1960s. He later co-founded the renowned Circle Repertory Company, for which he wrote many of his major works, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning Talley's Folly (1979). Through his dynamic characters, many of whom are misfits of low social -

Naked Came the Stranger - Wikipedia

Naked Came the Stranger - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naked_Came_the_Stranger Naked Came the Stranger From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Naked Came the Stranger is a 1969 novel written as a literary hoax poking fun at the American literary culture of its time. Though credited to "Penelope Ashe", it was in fact written by a group of twenty-four journalists led by Newsday columnist Mike McGrady. McGrady's intention was to write a book that was both deliberately terrible and contained a lot of descriptions of sex, to illustrate the point that popular American literary culture had become mindlessly vulgar. The book fulfilled the authors' expectations and became a bestseller in 1969; they revealed the hoax later that year, further spurring the book's popularity.[1] Contents 1 Hoax 2 Synopsis Cover of reissue of Naked Came the 3 Reception Stranger 4 Further reading 5 See also 6 References 7 External links Hoax Mike McGrady was convinced that popular American literary culture had become so base—with the best-seller lists dominated by the likes of Harold Robbins and Jacqueline Susann—that any book could succeed if enough sex was thrown in. To test his theory, in 1966 McGrady recruited a team of Newsday colleagues (according to Andreas Schroder,[2] nineteen men and five women) to collaborate on a sexually explicit novel with no literary or social value whatsoever. McGrady co-edited the project with his Newsday colleague Harvey Aronson, and among the other collaborators were well-known writers including 1965 Pulitzer Prize winner Gene Goltz, 1970 Pulitzer Prize winner Robert W. -

Arcade Publishing | Fall 2018 | 1

ARCADE PUBLISHING Fall 2018 Contact Information Editorial, Publicity, and Bookstore and Library Sales Field Sales Force Special Sales Distribution Elise Cannon Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. Two Rivers Distribution VP, Field Sales 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor Ingram Content Group LLC One Ingram Boulevard t: 510-809-3730 New York, NY 10018 e: [email protected] t: 212-643-6816 La Vergne, TN 37086 f: 212-643-6819 t: 866-400-5351 e: [email protected] Leslie Jobson e: [email protected] Field Sales Support Manager t: 510-809-3732 e: [email protected] International Sales Representatives United Kingdom, Ireland & Australia, New Zealand & India South Africa Canada Europe Shawn Abraham Peter Hyde Associates Thomas Allen & Son Ltd. General Inquiries: Manager, International Sales PO Box 2856 195 Allstate Parkway Ingram Publisher Services UK Ingram Publisher Services Intl Cape Town, 8000 Markham, ON 5th Floor 1400 Broadway, Suite 520 South Africa L3R 4T8 Canada 52–54 St John Street New York, NY, 10018 t: +27 21 447 5300 t: 800-387-4333 Clerkenwell t: 212-581-7839 f: +27 21 447 1430 f: 800-458-5504 London, EC1M 4HF e: shawn.abraham@ e: [email protected] e: [email protected] e: IPSUK_enquiries@ ingramcontent.com ingramcontent.co.uk India All Other Markets and Australia Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd. General International Enquiries Ordering Information: NewSouth Books 7th Floor, Infinity Tower C Ingram Publisher Services Intl Grantham Book Services Orders and Distribution DLF Cyber City, Phase - III 1400 Broadway,