Preparation of Pure Gallium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallium and Germanium Recovery from Domestic Sources

RI 94·19 REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS/1992 r---------~~======~ PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE FRCJIiI LIBRARY "\ LIBRARY SPOKANE RESEARCH CENTER RECEIVED t\ UG 7 1992 USBOREAtJ.OF 1.j,'NES E. S15't.ON1"OOMERY AVE. ~E. INA 00207 Gallium and Germanium Recovery From Domestic Sources By D. D. Harbuck UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF MINES Mission: As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has respon sibility for most of our nationally-owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering wise use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, pre serving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and pro viding for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interests of all our people. The Department also promotes the goals of the Take Pride in America campaign by encouragi,ng stewardship and citizen responsibil ity for the public lands and promoting citizen par ticipation in their care. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reser vation communities and for people who live in Island Territories under U.S. Administration. TIi Report of Investigations 9419 Gallium and Germanium Recovery From Domestic Sources By D. D. Harbuck I ! UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Manuel lujan, Jr., Secretary BUREAU OF MINES T S Ary, Director - Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data: Harbuck, D. D. (Donna D.) Ga1lium and germanium recovery from domestic sources / by D.D. -

Indium, Caesium Or Cerium Compounds for Treatment of Cerebral Disorders

Europaisches Patentamt 298 644 J European Patent Office Oy Publication number: 0 A3 Office europeen des brevets EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION © Application number: 88305895.0 © intci.s A61K 31/20, A61K 31/28, A61K 33/24 @ Date of filing: 29.06.88 © Priority: 07.07.87 GB 8715914 © Applicant: EFAMOL HOLDINGS PLC Efamol House Woodbridge Meadows © Date of publication of application: Guildford Surrey GU1 1BA(GB) 11.01.89 Bulletin 89/02 @ Inventor: Horrobin, David Frederick © Designated Contracting States: c/o Efamol House Woodbridge Meadows AT BE CH DE ES FR GB GR IT LI LU NL SE Guildford Surrey GU1 1BA(GB) Inventor: Corrigan, Frank ® Date of deferred publication of the search report: c/o Argyll & Bute Hospital 14.11.90 Bulletin 90/46 Lochgilphead, Argyll PA3T 8ED Scotland(GB) © Representative: Caro, William Egerton et al J. MILLER & CO. Lincoln House 296-302 High Holborn London WC1V 7 JH(GB) © Indium, caesium or cerium compounds for treatment of cerebral disorders. © A method of treatment of schizophrenia or other chronic cerebral disorder in which cerebral atrophy is shown, is characterised in that one or more as- similable or pharmaceutically acceptable indium caesium or cerium compounds is associated with a pharmaceutically acceptable diluent or carrier. CO < CD 00 O> Xerox Copy Centre PARTIAL EUROPEAN SEARCH REPORT Application number European Patent J which under Rule 45 of the European Patent Convention Office shall be considered, for the purposes of subsequent EP 88 30 5895 proceedings, as the European search report DOCUMENTS CONSIDERED TO BE RELEVANT Citation of document with indication, where appropriate, Relevant CLASSIFICATION OF THE ategory of relevant passages to claim APPLICATION (Int. -

The Infrared Spectrum of Indium in Silicon Revisited A

The infrared spectrum of indium in silicon revisited A. Tardella, B. Pajot To cite this version: A. Tardella, B. Pajot. The infrared spectrum of indium in silicon revisited. Journal de Physique, 1982, 43 (12), pp.1789-1795. 10.1051/jphys:0198200430120178900. jpa-00209562 HAL Id: jpa-00209562 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/jpa-00209562 Submitted on 1 Jan 1982 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. J. Physique 43 (1982) 1789-1795 DTCEMBRE 1982, 1789 Classification Physics Abstracts 71.55 - 78.50 The infrared spectrum of indium in silicon revisited A. Tardella and B. Pajot Groupe de Physique des Solides de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure, Université Paris VII, Tour 23, 2, place Jussieu, 75251 Paris Cedex 05, France (Reçu le 27 mai 1982, révisé le 22 juillet, accepté le 23 août 1982) Résumé. 2014 Le spectre d’absorption de l’indium dans le silicium a été mesuré dans des conditions où l’élargisse- ment des raies par effet de concentration est négligeable. Avec une résolution appropriée, on détecte 17 transitions et les composantes d’un doublet serré sont attribuées à deux transitions calculées. A 6 K, la largeur intrinsèque des raies varie de 2,6 à 0,8 cm-1, ce qui indique un effet lié à la structure de la bande de valence du silicium. -

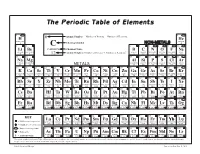

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

Unit 2 Matter and Chemical Change

TOPIC 5 The Periodic Table By the 1850s, chemists had identified a total of 58 elements, and nobody knew how many more there might be. Chemists attempted to create a classification system that would organize their observations. The various “family” systems were useful for some elements, but most family relationships were not obvious. What else could a classification system be based on? By the 1860s several scientists were trying to sort the known elements according to atomic mass. Atomic mass is the average mass of an atom of an element. According to Dalton’s atomic theory, each element had its own kind of atom with a specific atomic mass, different from the Figure 2.31 Dmitri atomic mass of any other elements. One scientist created a system that Ivanovich Mendeleev was so accurate it is still used today. He was a Russian chemist named was born in Siberia, the Dmitri Mendeleev (1834–1907). youngest of 17 children. Mendeleev Builds a Table Mendeleev made a card for each known element. On each card, he put data similar to the data you see in Figure 2.32. Figure 2.32 The card above shows modern values for silicon, rather than the ones Mendeleev actually used. His values were surprisingly close to modern ones. The atomic mass measurement indicates that silicon is 28.1 times heavier than hydrogen. You can observe other properties of silicon in Figure 2.33. Mendeleev pinned all the cards to the wall, in order of increasing atomic mass. He “played cards” for several Figure 2.33 The element silicon is melted months, arranging the elements in vertical columns and and formed into a crystal. -

Soldering to Gold Films

Soldering to Gold Films THE IMPORTANCE OF LEAD-INDIUM ALLOYS Frederick G. Yost Sandia Laboratories, Albuquerque, New Mexico, U.S.A. Reliable solder joints can be made on gold metallised microcircuits using lead-indium solders providing certain important conditions are understood and carefully controlled. This paper reviews the three fundamental concepts of scavenging, wetting, and ageing, which are relevant when soldering to gold films. Alloys containing indium have been used for solder- sition and a body centred tetragonal space lattice. ing electronic components to thin gold films and wires Although considerable work has been addressed for at least 14 years. Braun (1, 2) investigated the to the question of clustering and phase separation potential of several multicomponent alloys based in the a field below 20°C (7, 8, 9) the practical signifi- upon the lead-tin-indium ternary alloy system. cance of this phenomenon has not yet materialised. More recently, work on lead-indium binary alloys The most commonly used alloy is the 50 weight has been reported by Jackson (3) and Yost, et al per cent indium composition which has a liquidus (4, 5, 6). In this paper we intend to define, to discuss, temperature of approximately 210°C and a solidus and to illustrate three fundamental concepts relevant temperature of approximately 185°C. Alloys in the to soldering to gold films using lead-indium solders. lead rich phase field, a, freeze dendritically by The lead-indium phase diagram, shown in Figure forming lead rich stalks. The formation of these 1, contains a wealth of useful solder alloys having dendrites causes a surface rumpling which gives the solidus temperatures which range from 156.6°C solder surface a somewhat frosty rather than a shiny (pure indium) to 327.5 °C (pure lead). -

Atomic Weight of Gallium, Weighed Portions of the Pure Metal Were Converted to the Hydroxide, the Sulphate, and the Nitrate, Respectively

- -----.---.--~---------~---------------- U. S. D EPARTMENT OF C OMMERCE N ATIONAL B UREAU OF STANDARDS RESEARCH PAPER RP838 Part of Journal of Research of the J\[ational Bureau of Standards, V olume 15, October 1935 ATOMIC WEIGHT OF GALLI UM By G. E. F. Lundell and James I. Hoffman ABSTRACT In this determination of the atomic weight of gallium, weighed portions of the pure metal were converted to the hydroxide, the sulphate, and the nitrate, respectively. These were then beated until they were changed to the oxide, Ga20 a, which was finally ignited at 1,200 to 1,300° C. By this procedure, the atomic weight is related dir~ctly to that of oxygen. Preliminary tests showed that the metal was free from an appreciable film of oxide and did not contain occluded gases. The highly ignited oxide, obtained through the hydroxide or the sulphate, contained no gases and was not appreciably hygroscopic. The oxide obtained by igniting the nitrate was less satisfactory. To make possible the correction of the weights to the vacuum standard, the density of the oxide was also determined, and found to be 5.95 g/cm3• The value for the atomic weight based on this work is 69.74. CONT E N TS Page I. Introduction ___________ _____ _________________ ____ ___________ ___ 409 II. Preliminary tests ______ ________ ___ _____ ____ ___ _____________ _____ 410 III. Preparation and testing of materials used _________ _________________ 412 1. Metallic gallium _______________________________________ ___ 412 (a) Preparation ___ _________ _____ ____ ______ _____ ____ ___ _ 412 (b) Tests for occluded gases _____________________________ _ 412 (c) Tests for a film of oxide on the surface of the crystals ____ 413 (d) Test for chlorides in the crystals of metallic gallium ______ 414 2. -

The Gallium Melting-Point Standard

TECH NATL INST. OF STAND & AlllDb 312iab /0/Vs Z NBS SPECIAL PUBLICATION 481 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE / National Bureau of Standards Gallium Melting-point Standard NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS National The Bureau of Standards^ was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to pro- mote public safety. The Bureau consists of the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research, the Institute for Applied Technology, the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology, the Office for Information Programs, and the Office of Experimental Technology Incentives Program. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consist- ent system of physical measurement; coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essen- tial services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. The Institute consists of the Office of Measurement Services, and the following center and divisions: Applied Mathematics — Electricity — Mechanics — Heat — Optical Physics — Center for Radiation Research — Lab- oratory Astrophysics- — Cryogenics^ — Electromagnetics"' — Time and Frequency". THE INSTITUTE FOR MATERIALS RESEARCH conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measure- ment, standards, and data on the properties of well-characterized materials needed by industry, commerce, educational insti- tutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government agencies; and develops, produces, and distributes standard reference materials. -

Geology and Mineralogy of the Ape.X Washington County, Utah

Geology and Mineralogy of the Ape.x Germanium-Gallium Mine, Washington County, Utah Geology and Mineralogy of the Apex Germanium-Gallium Mine, Washington County, Utah By LAWRENCE R. BERNSTEIN U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1577 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL HODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1986 For sale by the Distribution Branch, Text Products Section U.S. Geological Survey 604 South Pickett St. Alexandria, VA 22304 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bernstein, Lawrence R. Geology and mineralogy of the Apex Germanium Gallium mine, Washington County, Utah (U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1577) Bibliography: p. 9 Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.3:1577 1. Mines and mineral resources-Utah-Washington County. 2. Mineralogy-Utah-Washington County. 3. Geology-Utah-Wasington County. I. Title. II. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Bulletin 1577. QE75.B9 no. 1577 557.3 s 85-600355 [TN24. U8] [553' .09792'48] CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Germanium and gallium 1 Apex Mine 1 Acknowledgments 3 Methods 3 Geologic setting 3 Regional geology 3 Local geology 3 Ore geology 4 Mineralogy 5 Primary ore 5 Supergene ore 5 Discussion and conclusions 7 Primary ore deposition 7. Supergene alteration 8 Implications 8 References 8 FIGURES 1. Map showing location of Apex Mine and generalized geology of surrounding region 2 2. Photograph showing main adit of Apex Mine and gently dipping beds of the Callville Limestone 3 3. Geologic map showing locations of Apex and Paymaster mines and Apex fault zone 4 4. Scanning electron photomicrograph showing plumbian jarosite crystals from the 1,601-m level, Apex Mine 6 TABLES 1. -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. -

Highly Selective and Rapid Uptake of Radionuclide Cesium

Article pubs.acs.org/cm Highly Selective and Rapid Uptake of Radionuclide Cesium Based on Robust Zeolitic Chalcogenide via Stepwise Ion-Exchange Strategy † † † † † † † Huajun Yang, Min Luo, Li Luo, Hongxiang Wang, Dandan Hu, Jian Lin, Xiang Wang, ‡ ‡ § ⊥ † Yanlong Wang, Shuao Wang, Xianhui Bu,*, Pingyun Feng,*, and Tao Wu*, † College of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Soochow University, Jiangsu 215123, China ‡ School for Radiological and Interdisciplinary Sciences (RAD-X), Soochow University, Jiangsu 215123, China § Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, California State University Long Beach, 1250 Bellflower Boulevard, Long Beach, California 90840, United States ⊥ Department of Chemistry, University of California, Riverside, Riverside, California 92521, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: The safe use of nuclear energy requires the development of advanced adsorbent technology to address environment damage from nuclear waste or accidental release of radionuclides. Recently developed amine-directed chalcogenide frameworks have intrinsic advantages as ion-exchange materials to capture radionuclides, because their exceptionally negative framework charge can lead to high cation-uptake capacity and their 3-D multidimensional intersecting channel promotes rapid ion diffusion and offer a unique kinetic advantage. Prior to this work, however, such advantages could not be realized because organic cations in the as-synthesized materials are sluggish during ion exchange. Here we report an ingenious approach on the activation of amine- directed zeolitic chalcogenides through a stepwise ion-exchange strategy and their use in cesium adsorption. The activated porous chalcogenide exhibits highly enhanced cesium uptake compared to the pristine form and is comparable to the best metal chalcogenide sorbents so far. Further ion-exchange experiments in the presence of competing ions confirm the high selectivity for cesium ions. -

Genius of the Periodic Table

GENIUS OF THE PERIODIC TABLE "Isn't it the work of a genius'. " exclaimed Academician V.I. Spitsyn, USSR, a member of the Scientific Advisory Committee when talking to an Agency audience in January. His listeners shared his enthusiasm. Academician Spitsyn was referring to the to the first formulation a hundred years ago by Professor Dmitry I. Mendeleyev of the Periodic Law of Elements. In conditions of enormous difficulty, considering the lack of data on atomic weights of elements, Mendeleyev created in less than two years work at St. Petersburg University, a system of chemical elements that is, in general, still being used. His law became a powerful instrument for further development of chemistry and physics. He was able immediately to correct the atomic weight numbers of some elements, including uranium, whose atomic weight he found to be double that given at the time. Two years later Mendeleyev went so far as to give a detailed description of physical or chemical properties of some elements which were as yet undiscovered. Time gave striking proof of his predictions and his periodic law. Mendeleyev published his conclusions in the first place by sending, early in March 186 9, a leaflet to many Russian and foreign scientists. It gave his system of elements based on their atomic weights and chemical resemblance. On the 18th March that year his paper on the subject was read at the meeting of the Russian Chemical Society, and two months later the Society's Journal published his article entitled "The correlation between properties of elements and their atomic weight".