Unit 2 Matter and Chemical Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carbothermal Synthesis of Silicon Nitride

Carbothermal Synthesis of Silicon Nitride Xiaohan Wan A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Materials Science and Engineering Faculty of Science March 2013 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Wan First name: Xiaohan Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: Materials Science and Engineering Faculty: Science Title: Carbothermal synthesis of silicon nitride Abstract 350 words maximum Carbothermal synthesis of silicon nitride Si3N4 followed by decomposition of Si3N4 is a novel approach to production of solar-grade silicon. The aim of the project was to study reduction/nitridation of silica under different conditions and to establish mechanism of silicon nitride formation. Carbothermal reduction of quartz and amorphous silica was investigated in a fixed bed reactor at 1300-1650 °C in nitrogen at 1-11 atm pressure and in hydrogen-nitrogen mixtures at atmospheric pressure. Samples were prepared from silica-graphite mixtures in the form of pellets. Carbon monoxide evolution in the reduction process was monitored using an infrared sensor; oxygen, nitrogen and carbon contents in reduced samples were determined by LECO analyses. Phases formed in the reduction process were analysed by XRD. Silica was reduced to silicon nitride and silicon carbide; their ratio was dependent on reduction time, temperature and nitrogen pressure. Reduction products also included SiO gas which was removed from the pellet with the flowing gas. In the experiments, reduction of silica started below 1300 °C; the reduction rate increased with increasing temperature. Silicon carbide was the major reduction product at the early stage of reduction; the fraction of silicon nitride increased with increasing reaction time. -

Gallium and Germanium Recovery from Domestic Sources

RI 94·19 REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS/1992 r---------~~======~ PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE FRCJIiI LIBRARY "\ LIBRARY SPOKANE RESEARCH CENTER RECEIVED t\ UG 7 1992 USBOREAtJ.OF 1.j,'NES E. S15't.ON1"OOMERY AVE. ~E. INA 00207 Gallium and Germanium Recovery From Domestic Sources By D. D. Harbuck UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF MINES Mission: As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has respon sibility for most of our nationally-owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering wise use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, pre serving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and pro viding for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interests of all our people. The Department also promotes the goals of the Take Pride in America campaign by encouragi,ng stewardship and citizen responsibil ity for the public lands and promoting citizen par ticipation in their care. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reser vation communities and for people who live in Island Territories under U.S. Administration. TIi Report of Investigations 9419 Gallium and Germanium Recovery From Domestic Sources By D. D. Harbuck I ! UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Manuel lujan, Jr., Secretary BUREAU OF MINES T S Ary, Director - Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data: Harbuck, D. D. (Donna D.) Ga1lium and germanium recovery from domestic sources / by D.D. -

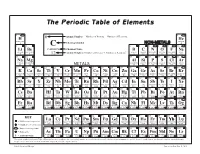

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

The Preparation and Reactions of the Lower Chlorides and Oxychlorides of Silicon Joseph Bradley Quig Iowa State College

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1926 The preparation and reactions of the lower chlorides and oxychlorides of silicon Joseph Bradley Quig Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Inorganic Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Quig, Joseph Bradley, "The preparation and reactions of the lower chlorides and oxychlorides of silicon " (1926). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14278. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14278 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UlVli films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and impiroper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. -

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

Atomic Weight of Gallium, Weighed Portions of the Pure Metal Were Converted to the Hydroxide, the Sulphate, and the Nitrate, Respectively

- -----.---.--~---------~---------------- U. S. D EPARTMENT OF C OMMERCE N ATIONAL B UREAU OF STANDARDS RESEARCH PAPER RP838 Part of Journal of Research of the J\[ational Bureau of Standards, V olume 15, October 1935 ATOMIC WEIGHT OF GALLI UM By G. E. F. Lundell and James I. Hoffman ABSTRACT In this determination of the atomic weight of gallium, weighed portions of the pure metal were converted to the hydroxide, the sulphate, and the nitrate, respectively. These were then beated until they were changed to the oxide, Ga20 a, which was finally ignited at 1,200 to 1,300° C. By this procedure, the atomic weight is related dir~ctly to that of oxygen. Preliminary tests showed that the metal was free from an appreciable film of oxide and did not contain occluded gases. The highly ignited oxide, obtained through the hydroxide or the sulphate, contained no gases and was not appreciably hygroscopic. The oxide obtained by igniting the nitrate was less satisfactory. To make possible the correction of the weights to the vacuum standard, the density of the oxide was also determined, and found to be 5.95 g/cm3• The value for the atomic weight based on this work is 69.74. CONT E N TS Page I. Introduction ___________ _____ _________________ ____ ___________ ___ 409 II. Preliminary tests ______ ________ ___ _____ ____ ___ _____________ _____ 410 III. Preparation and testing of materials used _________ _________________ 412 1. Metallic gallium _______________________________________ ___ 412 (a) Preparation ___ _________ _____ ____ ______ _____ ____ ___ _ 412 (b) Tests for occluded gases _____________________________ _ 412 (c) Tests for a film of oxide on the surface of the crystals ____ 413 (d) Test for chlorides in the crystals of metallic gallium ______ 414 2. -

Directed Gas Phase Formation of Silicon Dioxide and Implications for the Formation of Interstellar Silicates

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03172-5 OPEN Directed gas phase formation of silicon dioxide and implications for the formation of interstellar silicates Tao Yang 1,2, Aaron M. Thomas1, Beni B. Dangi1,3, Ralf I. Kaiser 1, Alexander M. Mebel 4 & Tom J. Millar 5 1234567890():,; Interstellar silicates play a key role in star formation and in the origin of solar systems, but their synthetic routes have remained largely elusive so far. Here we demonstrate in a combined crossed molecular beam and computational study that silicon dioxide (SiO2) along with silicon monoxide (SiO) can be synthesized via the reaction of the silylidyne radical (SiH) with molecular oxygen (O2) under single collision conditions. This mechanism may provide a low-temperature path—in addition to high-temperature routes to silicon oxides in circum- stellar envelopes—possibly enabling the formation and growth of silicates in the interstellar medium necessary to offset the fast silicate destruction. 1 Department of Chemistry, University of Hawai’iatMānoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA. 2 State Key Laboratory of Precision Spectroscopy, East China Normal University, Shanghai, 200062, China. 3 Department of Chemistry, Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, Tallahassee, FL 32307, USA. 4 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, USA. 5 Astrophysics Research Centre, School of Mathematics and Physics, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, BT7 1NN, UK. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to R.I.K. (email: [email protected]) or to A.M.M. (email: mebela@fiu.edu) or to T.J.M. (email: [email protected]) NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2018) 9:774 | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03172-5 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03172-5 — 28 + 28 + he origin of interstellar silicate grains nanoparticles ( SiO2 ), and 44 ( SiO ). -

Periodic Trends Lab CHM120 1The Periodic Table Is One of the Useful

Periodic Trends Lab CHM120 1The Periodic Table is one of the useful tools in chemistry. The table was developed around 1869 by Dimitri Mendeleev in Russia and Lothar Meyer in Germany. Both used the chemical and physical properties of the elements and their tables were very similar. In vertical groups of elements known as families we find elements that have the same number of valence electrons such as the Alkali Metals, the Alkaline Earth Metals, the Noble Gases, and the Halogens. 2Metals conduct electricity extremely well. Many solids, however, conduct electricity somewhat, but nowhere near as well as metals, which is why such materials are called semiconductors. Two examples of semiconductors are silicon and germanium, which lie immediately below carbon in the periodic table. Like carbon, each of these elements has four valence electrons, just the right number to satisfy the octet rule by forming single covalent bonds with four neighbors. Hence, silicon and germanium, as well as the gray form of tin, crystallize with the same infinite network of covalent bonds as diamond. 3The band gap is an intrinsic property of all solids. The following image should serve as good springboard into the discussion of band gaps. This is an atomic view of the bonding inside a solid (in this image, a metal). As we can see, each of the atoms has its own given number of energy levels, or the rings around the nuclei of each of the atoms. These energy levels are positions that electrons can occupy in an atom. In any solid, there are a vast number of atoms, and hence, a vast number of energy levels. -

Properties of Silicon Hafensteiner

Baran Lab Properties of Silicon Hafensteiner Si vs. C Siliconium Ion - Si is less electronegative than C - Not believed to exist in any reaction in solution - More facile nucleophilic addition at Si center J. Y. Corey, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 3237 - Pentacoordinate Si compounds have been observed Average BDE (kcal/mol) MeSiF4 NEt4 Ph3SiF2 NR4 C–C C–Si Si–Si C–F Si–F 83 76 53 116 135 - Lack of cation justified by high rate of bimolecular reactivity at Si C–O Si–O C–H Si–H Mechanism of TMS Deprotection 86 108 83 76 OTMS O Average Bond Lengths (Å) C–C C–Si C–O Si–O 1.54 1.87 1.43 1.66 Workup Si Si Silicon forms weak p-Bonds O O F F NBu4 p - C–C = 65 kcal/mol p - C–Si = 36 kcal/mol Pentavalent Silicon Baran Lab Properties of Silicon Hafensteiner Nucleophilic addition to Si b-Silicon effect and Solvolysis F RO–SiMe3 RO F–SiMe3 SiMe3 Me H H vs. Me3C H Me3C H OSiMe O Li 3 H OCOCF H OCOCF MeLi 3 3 A B Me-SiMe3 12 kA / kB = 2.4 x 10 Duhamel et al. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 2232 H H SiMe Me b-Silicon Effect 3 vs. Me3C H Me3C H - Silicon stabalizes b-carbocations H OCOCF3 H OCOCF3 - Stabalization is a result of hyperconjugation 4 kA / kB = 4 x 10 SiR3 CR3 Evidence for Stepwise mechanism vs. Me3Si SiMe2Ph SiMe2Ph A B Me3Si SiMe2Ph *A is more stable than B by 38 kcal/mol * Me3Si SiMe2Ph Me3Si Jorgensen, JACS, 1986,107, 1496 Product ratios are equal from either starting material suggesting common intermediate cation Baran Lab Properties of Silicon Hafensteiner Evidence for Rapid Nucleophilic Attack Extraordinary Metallation Me SiMe3 SiMe3 Li Si t-BuLi Me SnCl4 Cl Me3Si Cl Me2Si Cl SiMe MeO OMe 3 OMe OMe Me2Si Cl vs. -

The Gallium Melting-Point Standard

TECH NATL INST. OF STAND & AlllDb 312iab /0/Vs Z NBS SPECIAL PUBLICATION 481 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE / National Bureau of Standards Gallium Melting-point Standard NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS National The Bureau of Standards^ was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to pro- mote public safety. The Bureau consists of the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research, the Institute for Applied Technology, the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology, the Office for Information Programs, and the Office of Experimental Technology Incentives Program. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consist- ent system of physical measurement; coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essen- tial services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. The Institute consists of the Office of Measurement Services, and the following center and divisions: Applied Mathematics — Electricity — Mechanics — Heat — Optical Physics — Center for Radiation Research — Lab- oratory Astrophysics- — Cryogenics^ — Electromagnetics"' — Time and Frequency". THE INSTITUTE FOR MATERIALS RESEARCH conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measure- ment, standards, and data on the properties of well-characterized materials needed by industry, commerce, educational insti- tutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government agencies; and develops, produces, and distributes standard reference materials. -

Geology and Mineralogy of the Ape.X Washington County, Utah

Geology and Mineralogy of the Ape.x Germanium-Gallium Mine, Washington County, Utah Geology and Mineralogy of the Apex Germanium-Gallium Mine, Washington County, Utah By LAWRENCE R. BERNSTEIN U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1577 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL HODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1986 For sale by the Distribution Branch, Text Products Section U.S. Geological Survey 604 South Pickett St. Alexandria, VA 22304 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bernstein, Lawrence R. Geology and mineralogy of the Apex Germanium Gallium mine, Washington County, Utah (U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1577) Bibliography: p. 9 Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.3:1577 1. Mines and mineral resources-Utah-Washington County. 2. Mineralogy-Utah-Washington County. 3. Geology-Utah-Wasington County. I. Title. II. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Bulletin 1577. QE75.B9 no. 1577 557.3 s 85-600355 [TN24. U8] [553' .09792'48] CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Germanium and gallium 1 Apex Mine 1 Acknowledgments 3 Methods 3 Geologic setting 3 Regional geology 3 Local geology 3 Ore geology 4 Mineralogy 5 Primary ore 5 Supergene ore 5 Discussion and conclusions 7 Primary ore deposition 7. Supergene alteration 8 Implications 8 References 8 FIGURES 1. Map showing location of Apex Mine and generalized geology of surrounding region 2 2. Photograph showing main adit of Apex Mine and gently dipping beds of the Callville Limestone 3 3. Geologic map showing locations of Apex and Paymaster mines and Apex fault zone 4 4. Scanning electron photomicrograph showing plumbian jarosite crystals from the 1,601-m level, Apex Mine 6 TABLES 1. -

Periodic Table of the Elements Notes

Periodic Table of the Elements Notes Arrangement of the known elements based on atomic number and chemical and physical properties. Divided into three basic categories: Metals (left side of the table) Nonmetals (right side of the table) Metalloids (touching the zig zag line) Basic Organization by: Atomic structure Atomic number Chemical and Physical Properties Uses of the Periodic Table Useful in predicting: chemical behavior of the elements trends properties of the elements Atomic Structure Review: Atoms are made of protons, electrons, and neutrons. Elements are atoms of only one type. Elements are identified by the atomic number (# of protons in nucleus). Energy Levels Review: Electrons are arranged in a region around the nucleus called an electron cloud. Energy levels are located within the cloud. At least 1 energy level and as many as 7 energy levels exist in atoms Energy Levels & Valence Electrons Energy levels hold a specific amount of electrons: 1st level = up to 2 2nd level = up to 8 3rd level = up to 8 (first 18 elements only) The electrons in the outermost level are called valence electrons. Determine reactivity - how elements will react with others to form compounds Outermost level does not usually fill completely with electrons Using the Table to Identify Valence Electrons Elements are grouped into vertical columns because they have similar properties. These are called groups or families. Groups are numbered 1-18. Group numbers can help you determine the number of valence electrons: Group 1 has 1 valence electron. Group 2 has 2 valence electrons. Groups 3–12 are transition metals and have 1 or 2 valence electrons.