Low Status Increases Exposure to Altruistic Punishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisner, NE Saturday, August 17, 2019

Wisner, NE Saturday, August 17, 2019 Modified 2 Wheel Drive Driver Name (hook position) City / State Vehicle Name Vehicle Description Distance Points 1 Donald Nelson Cat Spring TX Lil Whip 2008 Chevy S-10 318.86 28 2 Robert Zajicek Columbus TX Gun Smoke 1923 T-Bucket 313.3 26 3 Cole Zajicek Columbus Tx Texas 2 Step 1923 T-Bucket 313.01 25 4 Lynn Stumme Waverly IA Heartbeat 312.7 0 5 Randy Wendling Manchester IA Special Delivery 302.85 24 6 Donald Nelson Cat Spring TX Bullwhip Mortorsports 302.51 23 7 Timothy Fitzsimmons Macon MO Pro Dezigns 297.55 22 8 Timothy Fitzsimmons Macon MO Country Heat 1925 Ford T Bucket 297.48 21 9 Richard Morris Neosho MO Buffalo's Chip 297.16 20 10 Dustin Corliss Cat Spring TX Run & Tell It 294.78 19 11 Cameron Paschall McAdoo TX High Cotton 293.48 18 12 Thomas Kimmons Farmersville TX Kicking & Screaming 285.79 17 13 Michael Sulley Wiggins CO Bully 212.5 0 14 Scott Jensen Dell Rapids SD American Ethanol 30.58 16 15 Shannon Kuluman Springer NM Poor Boy 1 0 16 Jake Miller Whitewright TX Bad Decisions 300.39 DQ 14.5 16 Jarrod Wiens Beatrice NE Inheritance 292.03 DQ 14.5 Wisner, NE Saturday, August 17, 2019 Modified 4 Wheel Drive Driver Name (hook position) City / State Vehicle Name Vehicle Description Distance Points 1 Nick Christensen Cumblerland IA Nuttin Honey 2002 Ford Ranger 328.01 28 2 Rick Johnson Powell Wy Bad Bowtie 320.38 0 3 Jamie Busch Mason City IA Thunder Struck/4WD 318.75 26 4 Darren Kriz Tyndall SD Wild Child 98 Ford Ranger 315.95 25 5 Dustin Ridder Hermann MO Stroker 2003 Ford F350 314.1 24 6 -

The Other Face of Fanaticism

February 2, 2003 The Other Face of Fanaticism By PANKAJ MISHRA New York Times Magazine On the evening of Jan. 30, 1948, five months after the independence and partition of India, Mohandas Gandhi was walking to a prayer meeting on the grounds of his temporary home in New Delhi when he was shot three times in the chest and abdomen. Gandhi was then 78 and a forlorn figure. He had been unable to prevent the bloody creation of Pakistan as a separate homeland for Indian Muslims. The violent uprooting of millions of Hindus and Muslims across the hastily drawn borders of India and Pakistan had tainted the freedom from colonial rule that he had so arduously worked toward. The fasts he had undertaken in order to stop Hindus and Muslims from killing one another had weakened him, and when the bullets from an automatic pistol hit his frail body at point-blank range, he collapsed and died instantly. His assassin made no attempt to escape and, as he himself would later admit, even shouted for the police. Millions of shocked Indians waited for more news that night. They feared unspeakable violence if Gandhi's murderer turned out to be a Muslim. There was much relief, also some puzzlement, when the assassin was revealed as Nathuram Godse, a Hindu Brahmin from western India, a region relatively untouched by the brutal passions of the partition. Godse had been an activist in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (National Volunteers Association, or R.S.S.), which was founded in the central Indian city of Nagpur in 1925 and was devoted to the creation of a militant Hindu state. -

Judgment Day the Judgments and Sentences of 18 Horrific Australian Crimes

Judgment Day The judgments and sentences of 18 horrific Australian crimes EDITED BY BeN COLLINS Prelude by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC MANUSCRIPT FOR MEDIA USE ONLY NO CONTENT MUST BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT PERMISSION PLEASE CONTACT KARLA BUNNEY ON (03) 9627 2600 OR [email protected] Judgment Day The judgments and sentences of 18 horrific Australian crimes MEDIA GROUP, 2011 COPYRIGHTEDITED BY OF Be THEN COLLINS SLATTERY Prelude by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC Contents PRELUDE Taking judgments to the world by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC ............................9 INTRODUCTION Introducing the judgments by Ben Collins ...............................................................15 R v MARTIN BRYANT .......................................17 R v JOHN JUSTIN BUNTING Sentenced: 22 November, 1996 AND ROBERT JOE WAGNER ................222 The Port Arthur Massacre Sentenced: 29 October, 2003 The Bodies in the Barrels REGINA v FERNANDO ....................................28 Sentenced: 21 August, 1997 THE QUEEN and BRADLEY Killer Cousins JOHN MURDOCH ..............................................243 Sentenced: 15 December, 2005 R v ROBERTSON ...................................................52 Murder in the Outback Sentenced: 29 November, 2000 Deadly Obsession R v WILLIAMS .....................................................255 Sentenced: 7 May, 2007 R v VALERA ................................................................74 Fatboy’s Whims Sentenced: 21 December, 2000MEDIA GROUP, 2011 The Wolf of Wollongong THE QUEEN v McNEILL .............................291 -

The Mass Graves of Al-Mahawil: the Truth Uncovered

IRAQ 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org Vol. 15, No. 5 (E) – May 2003 (212) 290-4700 The chaotic and unprofessional manner in which the mass graves around al- Hilla and al-Mahawil were unearthed made it impossible for many of the relatives of missing persons to identify positively many of the remains, or even to keep the human remains intact and separate. In the absence of international assistance, Iraqis used a backhoe to dig up the mass grave, literally slicing through countless bodies and mixing up remains in the process. At the end of the process, more than one thousand remains at the al-Mahawil grave sites were again reburied without being identified. In addition, because no forensic presence existed at the site, crucial evidence necessary for future trials of the persons responsible for the mass executions was never collected, and indeed may have Relatives of the missing search through bags containing corpses recovered from a been irreparably destroyed. mass grave near Hilla. © 2003 Peter Bouckaert/Human Rights Watch THE MASS GRAVES OF AL-MAHAWIL: THE TRUTH UNCOVERED 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] May 2003 Vol.15, No.5 (E) IRAQ THE MASS GRAVES OF AL-MAHAWIL: THE TRUTH UNCOVERED Table of Contents I. -

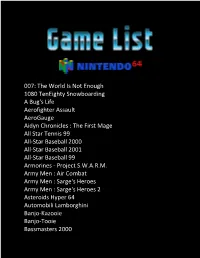

007: the World Is Not Enough 1080 Teneighty Snowboarding a Bug's

007: The World Is Not Enough 1080 TenEighty Snowboarding A Bug's Life Aerofighter Assault AeroGauge Aidyn Chronicles : The First Mage All Star Tennis 99 All-Star Baseball 2000 All-Star Baseball 2001 All-Star Baseball 99 Armorines - Project S.W.A.R.M. Army Men : Air Combat Army Men : Sarge's Heroes Army Men : Sarge's Heroes 2 Asteroids Hyper 64 Automobili Lamborghini Banjo-Kazooie Banjo-Tooie Bassmasters 2000 Batman Beyond : Return of the Joker BattleTanx BattleTanx - Global Assault Battlezone : Rise of the Black Dogs Beetle Adventure Racing! Big Mountain 2000 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Blast Corps Blues Brothers 2000 Body Harvest Bomberman 64 Bomberman 64 : The Second Attack! Bomberman Hero Bottom of the 9th Brunswick Circuit Pro Bowling Buck Bumble Bust-A-Move '99 Bust-A-Move 2: Arcade Edition California Speed Carmageddon 64 Castlevania Castlevania : Legacy of Darkness Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Charlie Blast's Territory Chopper Attack Clay Fighter : Sculptor's Cut Clay Fighter 63 1-3 Command & Conquer Conker's Bad Fur Day Cruis'n Exotica Cruis'n USA Cruis'n World CyberTiger Daikatana Dark Rift Deadly Arts Destruction Derby 64 Diddy Kong Racing Donald Duck : Goin' Qu@ckers*! Donkey Kong 64 Doom 64 Dr. Mario 64 Dual Heroes Duck Dodgers Starring Daffy Duck Duke Nukem : Zero Hour Duke Nukem 64 Earthworm Jim 3D ECW Hardcore Revolution Elmo's Letter Adventure Elmo's Number Journey Excitebike 64 Extreme-G Extreme-G 2 F-1 World Grand Prix F-Zero X F1 Pole Position 64 FIFA 99 FIFA Soccer 64 FIFA: Road to World Cup 98 Fighter Destiny 2 Fighters -

A Pause in the Mercy of God

A Pause in the Mercy of God A Preview of Things to Come – Part VII Revelation 15:1-8 Introduction All across the United States, millions of listeners reacted. Many in the New England area loaded up On Sunday, October 30, 1938, millions of radio their cars and fled their homes. People improvised listeners were shocked when news alerts announced gas masks. People were hysterical. They thought the the invasion of Earth by a species from Mars. The end was near. Scores of people around the country people panicked when they learned of the Martians’ flocked to churches to pray. ferocious and seemingly unstoppable attack on When the people learned the truth, millions were humanity. infuriated and Orson Welles was actually catapulted Orson Welles and his cast effectively fooled to fame. millions of radio listeners in their adaptation of a This idea was not really new. novel by H. G. Wells entitled, War of the Worlds . The script unfolded by interrupting a musical variety The British Broadcasting System a few years program normally run by the CBS radio network. before Orson Welles’ hoax had run a similar hoax This was a pre-television time when most people sat giving a play by play of a mass riot that was in their living rooms to listen to music and a variety sweeping through London. The result of this was of radio programs in the evenings. widespread panic as well. The musical program was interrupted with the We would think a hoax like this could not happen news that at 8:50 p.m. -

In the Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF WEST VIRGINIA STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA, Appellee, v. Supreme Court No. 34860 Circuit Court No. 96~F~42 BILL Y RAY MCLAUGHLIN, Appellant. RORY L. PERRY (I, CLERK SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF WEST VIRIGINIA BRIEF FOR APPELLANT ON CERTIFIED QUESTIONS Gregory L. Ayers Deputy Public Defender W.Va. Bar No. 7824 Kanawha County Public Defender Office Charleston, WV 25330 (304) 348-2323 Joseph A. Noggy Chief Public Defender W.Va. BarNo. 2745 Marcia L. Hebb Assistant Public Defender W.Va. Bar No. 7948 Raleigh County Public Defender Office 228 N. Fayette Street Beckley, WV 25801 (304) 253~ 7405 Counsel for Petitioner TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................................... .ii PROCEEDINGS AND RULINGS BELOW .................................................................................. 1 STATEMENT OF FACTS .............................................................................................................. 6 ASSIGNMENTS OF ERROR ......................................................................................................... 8 DISCUSSION OF LAW ................................................................................................................. 9 I. Absent Proper Instructions From The Court, W.Va. Code § 62-3-15 (1994) (2005 Repl. Vol.) Unconstitutionally (1) Shifts The Burden Of Persuasion On The Issue Of Mercy To The Defendant, (2) Provides No Standards For The Jury's Mercy Decision, and (3) Permits -

A Cultural Analysis of a Physicist ''Trio'' Supporting the Backlash Against

ARTICLE IN PRESS Global Environmental Change 18 (2008) 204–219 www.elsevier.com/locate/gloenvcha Experiences of modernity in the greenhouse: A cultural analysis of a physicist ‘‘trio’’ supporting the backlash against global warming Myanna Lahsenà Center for Science and Technology Policy Research, University of Colorado and Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Epaciais (INPE), Av. dos Astronautas, 1758, Sa˜o Jose´ dos Campos, SP 12227-010 Brazil Received 18 March 2007; received in revised form 5 October 2007; accepted 29 October 2007 Abstract This paper identifies cultural and historical dimensions that structure US climate science politics. It explores why a key subset of scientists—the physicist founders and leaders of the influential George C. Marshall Institute—chose to lend their scientific authority to this movement which continues to powerfully shape US climate policy. The paper suggests that these physicists joined the environmental backlash to stem changing tides in science and society, and to defend their preferred understandings of science, modernity, and of themselves as a physicist elite—understandings challenged by on-going transformations encapsulated by the widespread concern about human-induced climate change. r 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Anti-environmental movement; Human dimensions research; Climate change; Controversy; United States; George C. Marshall Institute 1. Introduction change itself, what he termed a ‘‘strong theory of culture.’’ Arguing that the essential role of science in our present age Human Dimensions Research in the area of global only can be fully understood through examination of environmental change tends to integrate a limited con- individuals’ relationships with each other and with ‘‘mean- ceptualization of culture. -

Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (University of North Carolina Press, 2016)

No Mercy Here 181 BOOK REVIEW Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (University of North Carolina Press, 2016) Viviane Saleh-Hanna* arah Haley’s NO MERCY HERE: GENDER, PUNIShmENT, AND THE MAKIng of Jim Crow Modernity is a beautifully written, empirical yet nuanced account of imprisoned and paroled Black women’s lives, deaths, and Sstruggles under convict leasing, chain gang, and parole regimes in Georgia at the turn of the twentieth century. Although the majority of Haley’s book focuses on Black women, she notes that 18 percent of Black female prison- ers were not yet 17 years old (42). One prisoner was 11 years old (96) at the time of her sentencing. The majority were young adults, many in their early twenties, some remaining imprisoned for decades. All, regardless of age, were sentenced to hard labor. Haley ties together wide-ranging archival data gathered from criminal justice agency reports and proceedings, government-sponsored commissions to examine prison and labor conditions, petitions and clemency applica- tions, letters, newspaper articles, era-specific research, Black women’s blues, historic speeches, and other social movement materials. This breadth of data coupled with Haley’s Black feminist analysis and methodology unearths the issues of Black women’s imprisonment, abuse, rape, and forced labor under Jim Crow’s carceral push into modernity. Haley also presents records of white women’s imprisonment, as well as their living and labor conditions, and discusses the responses these elicited from politicians, criminal justice agents, social organizations, and media outlets. Though the number of white women ensnared within Georgia’s * Viviane Saleh-Hanna is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Crime and Justice Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. -

From Acorn Stud Storm Bird Northern Dancer South Ocean Mujadil

From Acorn Stud 901 901 Northern Dancer Storm Bird South Ocean Mujadil (USA) Secretariat BAY FILLY (IRE) Vallee Secrete March 8th, 2004 Midou Lyphard Alzao Va Toujours Lady Rebecca (1987) Prince Regent French Princess Queen Dido E.B.F. Nominated. 1st dam VA TOUJOURS: 3 wins at 2 and 3 and £28,007 inc. Reference Point Strensall S., L., placed viz. 3rd Bottisham Heath Stud Rockfel S., Gr.3; dam of 4 previous foals; 3 runners; 3 winners: Polish Pilot (IRE) (95 g. by Polish Patriot (USA)): 4 wins, £30,203 viz. placed at 2; also 2 wins over hurdles and 2 wins over fences and placed 32 times. Dauphin (IRE) (93 g. by Astronef): 3 wins at 3 and 4 inc. Bollinger Champagne Challenge Series H., Ascot and placed 7 times. White Mountain (IRE) (02 c. by Monashee Mountain (USA)): 2 wins at 3, 2005. Thatjours (IRE) (96 f. by Thatching): unraced; dam of a winner: Somaly Mam (IRE): 2 wins at 2, 2004 in Italy and placed 3 times. 2nd dam FRENCH PRINCESS: 4 wins at 3 and 4 and placed; dam of 5 winners inc.: VA TOUJOURS (f. by Alzao (USA)): see above. French Flutter: 3 wins inc. winner at 3 and placed 5 times. Lady of Surana: unraced; dam of 9 winners inc.: Alriffa (IND): 13 wins in India placed 2nd Nanoli Stud Juvenile Million, L. and 3rd Kingfisher Mysore 2000 Guineas, L. 3rd dam QUEEN DIDO (by Acropolis): winner at 2 and placed; dam of 3 winners inc.: ALIA: 5 wins at 3 inc. Princess Royal S., Gr.3, placed; dam of 6 winners. -

Death Don't Have No Mercy: a Memoir of a Mother's

To view this document as two-page spreads, go to the View menu in Acrobat Reader and select “Page Layout” and “Facing” Death Don’t Have No Mercy A Memoir of a Mother’s Death BY MARIANA CAPLAN Well Death will go in any family in this land Well Death will go in every family in this land Well he’ll come to your house and he won’t stay long Well you’ll look in the bed and one of your family will be gone Death will go in any family in this land FROM “DEATH DON’T HAVE NO MERCY,” BY REV. GARY DAVIS NOT MANY OF US have seen another person receive a death sentence. Fewer still have been present to watch their own mother be given the final verdict. I had returned just days before from Asia. Ironically, the intention of the trip was to sit at the famous cremation grounds of Varanasi in India and in Pashpatinath in Nepal, where funeral pyres have burned for thousands of years. I was trying to face death as intimately as possible, to take the next step in a lifetime struggle to come to terms with my ultimate fate. A Jew by birth, I had been practicing for a decade under the guidance of Lee Lozowick in the Western Baul tradition, a rare synthesis that combines Vajrayana Buddhism with the devotional ecstasy of Vaisnava Hinduism, adapted to the needs of the contemporary Western practitioner. I engaged my experiment well, bearing witness to the death and decomposition of the body. -

God's Mercy and Justice in the Context of the Cosmic Conflict

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 2019 God's Mercy and Justice in the Context of the Cosmic Conflict Romero Luiz Da Silva Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Da Silva, Romero Luiz, "God's Mercy and Justice in the Context of the Cosmic Conflict" (2019). Master's Theses. 135. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/135 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT GOD'S MERCY AND JUSTICE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE COSMIC CONFLICT by Romero Luiz Da Silva Adviser: Jo Ann Davidson ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Thesis Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: GOD'S MERCY AND JUSTICE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE COSMIC CONFLICT Name of researcher: Romero Luiz Da Silva Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jo Ann Davidson, PhD Date completed: July 2019 Problem When it comes to the right balance concerning God’s character of mercy and justice in relation to His dealings with sin in its different manifestations, a number of theologians, as well as Christians in general, have struggled to harmonize the existence of these two attributes in all God’s actions toward sinners. This difficulty has led many to think of divine mercy and justice as attributes that cannot fit together in what is called the cosmic conflict between good and evil.