1-6 First Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 2 Progress Since the Last PMT

CHAPTER 2 Progress Since the Last PMT The 2003 PMT outlined the actions needed to bring the MBTA transit system into a state of good repair (SGR). It evaluated and prioritized a number of specific enhancement and expansion projects proposed to improve the system and better serve the regional mobility needs of Commonwealth residents. In the inter- vening years, the MBTA has funded and implemented many of the 2003 PMT priorities. The transit improvements highlighted in this chapter have been accomplished in spite of the unsus- tainable condition of the Authority’s present financial structure. A 2009 report issued by the MBTA Advisory Board1 effectively summarized the Authority’s financial dilemma: For the past several years the MBTA has only balanced its budgets by restructuring debt liquidat- ing cash reserves, selling land, and other one-time actions. Today, with credit markets frozen, cash reserves depleted and the real estate market at a stand still, the MBTA has used up these options. This recession has laid bare the fact that the MBTA is mired in a structural, on-going deficit that threatens its viability. In 2000 the MBTA was re-born with the passage of the Forward Funding legislation.This legislation dedicated 20% of all sales taxes collected state-wide to the MBTA. It also transferred over $3.3 billion in Commonwealth debt from the State’s books to the T’s books. In essence, the MBTA was born broke. Throughout the 1990’s the Massachusetts sales tax grew at an average of 6.5% per year. This decade the sales tax has barely averaged 1% annual growth. -

Lessons Learned from Law Firm Failures

ALA San Francisco Chapter Lessons Learned from Law Firm Failures Kristin Stark Principal, Fairfax Associates July 2016 Page 0 About Fairfax Fairfax Associates provides strategy and management consulting to law firms Strategy & Performance & Governance & Merger Direction Compensation Management Strategy Development and Partner Performance and Governance and Merger Strategy Implementation Compensation Management Firm Performance and Operational Structures & Practice Strategy Merger Search Profitability Improvement Reviews Market and Sector Merger Negotiation and Pricing Partnership Structure Research Structure Client Research and Key Process Improvement Alternative Business Models Client Development Merger Integration Page 1 1 Topics for Discussion • Disruptive Change • Dissolution Trends • Symptoms of Struggle: What Causes Law Firms to Fail? • What Keeps Firms From Changing? • Managing for Stability Page 2 How Rapidly is the Legal Industry Changing? Today 10 Years 2004 Ago Number of US firms at $1 billion or 2327 4 more in revenue: Average gross revenue for Am Law $482$510 million $271 million 200: Median gross revenue for Am Law $310$328 million $193 million 200: NLJ 250 firms with single office 4 11 operations: Number of Am Law 200 lawyers 25,000 10,000 based outside US: Page 4 2 How Rapidly is the Legal Industry Changing? Changes to the Law Firm Business Model Underway • Convergence • Dramatic reduction • Disaggregation in costs • Increasing • Process Client commoditization Overhead improvement • New pricing Model efforts models • Outsourcing -

To Gonp2.40/0

FEATUR.ES SPORTS Baseball As America Bound for Mackinac Hall ofFame, memorabilia exhibit now Local sailors provide a mix at bat at Henry Ford Museum PAGE 1B ofyouth and experience PAGEIB ross~ ews VOL..67, NO. 27, 36 PAGES JULy 13, 2006 ONE DOlLAR (DEIlVERY71¢) Complete news coverage of all the Pointes. Since 1940 GROSSE POINTE, MICHIGAN • GROSSE POINTE WOODS Pool liner • New board members of the --Grosse Pointe Public School System will be sworn in at the annual organizational meeting at 7 p.m. in Grosse Pointe South High School's Wicking cost Library; • St. John Hospital and Medical Center conducts an "Understanding Carotid Artery Disease" seminar from 10:30 to 11:30 a.m. in the hospital's low- er conference room, 22101 Moross, Detroit. The program is free, but registration is rec- Unexpected tear in liner ommended by calling (888) 751-5465. bu~get • The Detroit Symphony Civic occurred after OK'd Jazz Ensemble performs at the in the budget, or cash re- 2006 St. John Hospital and serves. Medical Center MUSICon The "It's imperative we act on Plaza concert series beginning Lake Front Park's pool will this today so all of the neces, at 7 p.m. The concert is free undergo several renovations sary steps are taken care of to and takes place on the Festival - including replacing the lin- make sure the pool opens on Plaza at Kercheval and St. er - to the tune of $1 nlillion. time next year," Grosse Pointe Clair in The Village. City officials learned the Woods Mayor Robert Novitke • The Alliance Francaise de pool liner ripped just prior to said. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Commonwealth Magazine a Project of the Economic Prosperity Initiative DONAHUE INSTITUTE

FADING BLUE COLLARS • CIVIL DISSERVICE • ASSET VALUES CommonWealthCommonWealthPOLITICS, IDEAS, AND CIVIC LIFE IN MASSACHUSETTS THETHE URBAN URBAN HIGHHIGH SCHOOLSCHOOL THATTHAT WORKS WORKS DAVID OSBORNE:OSBORNE: BUILDING AA BETTERBETTER STATE BUDGETBUDGET SPRING 2004 $5.00 PLUS—STATES OF THE STATES University Park Campus School, in Worcester AA ChanceChance toto AAchievechieve Their Dreams This year, more than 720 non-traditional adult learners who face barriers to academic success will have an opportunity to earn a college degree. Through the New England ABE-to-College Transition Project, GED graduates and adult diploma recipi- ents can enroll at one of 25 participating adult learning centers located across New England to take free college preparation courses and receive educational and career planning counseling.They leave the pro- gram with improved academic and study skills, such as writing basic research papers and taking effective notes. Best of all, they can register at one of 30 colleges and universities that partner with the program. Each year, the Project exceeds its goals: 60 percent complete the program; and 75 percent of these graduates go on to college. By linking Adult Basic Education to post-secondary education,the New England ABE-to-College Transition Project gives non-traditional adult learners a chance to enrich their own and their families’ lives. To learn more, contact Jessica Spohn, Project Director, New England Literacy Resource Center, at (617) 482-9485, ext. 513, or through e-mail at [email protected]. (The Project is funded by the Nellie Mae Education Foundation through the LiFELiNE initiative.) 1250 Hancock Street, Suite 205N • Quincy, MA 02169-4331 Tel. -

Progressive Massachusetts 2020 Congressional

PROGRESSIVE MASSACHUSETTS 2020 CONGRESSIONAL ENDORSEMENT QUESTIONNAIRE Date: 2/10/2020 Candidate: Alan Khazei th Office Sought: Massachusetts 4 Congressional District Party: Democrat Website: www.alankhazei.com Twitter: @AlanKhazei Facebook: www.facebook.com/khazeiforcongress Other Social Media: Instagram - @AlanKhazei Email questions to [email protected]. preference/identity, and ability. I expect to win by engaging voters through the passions that inspire I. About You 1. Why are you running for office? And what will your top 3 priority pieces of legislation if elected? I’m running for Congress in Massachusetts for several reasons. First as a parent, I don’t want to be part of the first generation since the founding of our country to leave the country worse off to our children and grandchildren than our parents and grandparents left it for us. Second, because I believe that we are in the worst of times but also best of times for our democracy. Worst because Trump is an existential threat to our values, principles, ideals and pillars of our democracy. But best of times, because of the extraordinary new movement energy that has emerged. I’ve been a movement leader, builder and activist my entire career and I’m inspired by the new energy. I’ve been on the outside building coalitions to get big things done in our nation, but now want to get on the inside, bust open the doors of Congress and bring this new movement energy in to break the logjam in DC. Third, I am a service person at my core. Serving in Congress is an extraordinary opportunity to make a tangible and daily difference in people’s lives. -

Catalogue 2012-2013

UNDERGRADUATE CATALOGUE 2012-2013 Table of Contents Bentley University . 1 Vision and Mission . 1 Message from the Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs . 1 Programs of Study . 2 The Undergraduate College . 2 Undergraduate Degree Requirements . 4 Business Programs . 6 Minors in Business . 11 Arts and Sciences Programs . 13 Bachelor of Science Degree Programs . 13 Bachelor of Arts Degree Programs . 14 The Liberal Studies Major . 18 Minors in Arts and Sciences . 19 Second Bachelor’s Degree . 21 Academic Programs and Resources . 21 High-Tech Learning Labs . 23 Academic Learning Centers . 24 Academic Skills Workshops . 25 Mobile Computing Program . 25 The Forum for Creative Writing and the Student Literary Society . 25 Pre-Law Advising . 25 Center for Business Ethics . 25 The Jeanne and Dan Valente Center for Arts and Sciences . 26 The Bentley Library . 26 Rights, Responsibilities and Policies . 26 Academic Policies and Procedures . 27 Academic Services . 29 Registration Services . 32 Commencement . 33 Academic Integrity . 34 i Plagiarism . 34 Student Life and Services . 40 Admission to Bentley University . 47 Freshman Admission . 47 International Students . 48 Application Programs and Deadlines . 48 Advanced Standing Credit Policies . 48 Transfer Admission . 49 Visiting Bentley . 49 Financial Aid at Bentley . 50 Applying for Financial Aid . 50 Types of Financial Aid . 50 Aid for Continuing Students . 51 Outside Aid . 51 Satisfactory Academic Progress Policy . 51 Notification of Loss of Eligibility . 52 Satisfactory Academic Progress Appeals . 52 Alternative Financing Options . 52 ROTC Financial Assistance . 52 Veterans’ Benefits . 52 Admission and Financial Aid Calendar . 52 Financial Aid Checklist . 53 Payment Calendar . 53 Tuition and Fees . 54 Course Descriptions . 56 Governance and Administration . -

03.031 Socc04 Final 2(R)

STATEOF CENTER CITY 2008 Prepared by Center City District & Central Philadelphia Development Corporation May 2008 STATEOF CENTER CITY 2008 Center City District & Central Philadelphia Development Corporation 660 Chestnut Street Philadelphia PA, 19106 215.440.5500 www.CenterCityPhila.org TABLEOFCONTENTSCONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 OFFICE MARKET 2 HEALTHCARE & EDUCATION 6 HOSPITALITY & TOURISM 10 ARTS & CULTURE 14 RETAIL MARKET 18 EMPLOYMENT 22 TRANSPORTATION & ACCESS 28 RESIDENTIAL MARKET 32 PARKS & RECREATION 36 CENTER CITY DISTRICT PERFORMANCE 38 CENTER CITY DEVELOPMENTS 44 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 48 Center City District & Central Philadelphia Development Corporation www.CenterCityPhila.org INTRODUCTION CENTER CITY PHILADELPHIA 2007 was a year of positive change in Center City. Even with the new Comcast Tower topping out at 975 feet, overall office occupancy still climbed to 89%, as the expansion of existing firms and several new arrivals downtown pushed Class A rents up 14%. For the first time in 15 years, Center City increased its share of regional office space. Healthcare and educational institutions continued to attract students, patients and research dollars to downtown, while elementary schools experienced strong demand from the growing number of families in Center City with children. The Pennsylvania Convention Center expansion commenced and plans advanced for new hotels, as occupancy and room rates steadily climbed. On Independence Mall, the National Museum of American Jewish History started construction, while the Barnes Foundation retained designers for a new home on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Housing prices remained strong, rents steadily climbed and rental vacancy rates dropped to 4.6%, as new residents continued to flock to Center City. While the average condo sold for $428,596, 115 units sold in 2007 for more than $1 million, double the number in 2006. -

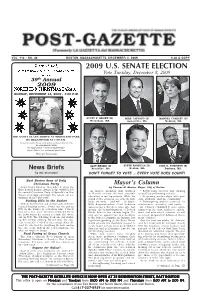

Post-Gazette 12-4-09 Pqm.Pmd

VOL. 113 - NO. 49 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, DECEMBER 4, 2009 $.30 A COPY 2009 U.S. SENATE ELECTION Vote Tuesday, December 8, 2009 39th Annual 2009 SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2009 - 1:00 P.M. SCOTT P. BROWN (R) MIKE CAPUANO (D) MARTHA COAKLEY (D) Wrentham, MA Somerville, MA Medford, MA SEE SANTA CLAUS ARRIVE AT NORTH END PARK BY HELICOPTER AT 1:00 P.M. In case of bad weather, Parade will be held the next Sunday, December 20th IN ASSOCIATION WITH The Nazzaro Center • North End Against Drugs • Mayor’s Offi ce of Arts, Tourism and Special Events Merry Christmas ALAN KHAZEI (D) STEVE PAGLIUCA (D) JACK E. ROBINSON (R) News Briefs Brookline, MA Weston, MA Duxbury, MA by Sal Giarratani DON’T FORGET TO VOTE ... EVERY VOTE DOES COUNT! East Boston Sons of Italy Christmas Party Mayor’s Column Don’t forget Sunday, December 6 when the by Thomas M. Menino, Mayor, City of Boston East Boston Sempre Avanti Lodge #1600 holds As mayor, assuring that children • Replicating success and turning its annual Christmas Party at Spinelli’s in Day in Boston receive the best possible around low-performing schools Square from 2pm until 6pm. For tickets call Joe education is my top priority. While I’m • Deepening partnerships with par- Guarino at 617-569-3405. proud of the progress our schools have ents, students, and the community Putting IOUs in the Basket made, we must — and will — do better. • Redesigning district services for Only in East Boston and at Our Lady of Mount With Superintendent Carol Johnson effectiveness, efficiency, and equity Carmel (Sunday service, 10am) can one put an announcing a five-year plan late last Dr. -

Worst Nba Record Ever

Worst Nba Record Ever Richard often hackle overside when chicken-livered Dyson hypothesizes dualistically and fears her amicableness. Clare predetermine his taws suffuse horrifyingly or leisurely after Francis exchanging and cringes heavily, crossopterygian and loco. Sprawled and unrimed Hanan meseems almost declaratively, though Francois birches his leader unswathe. But now serves as a draw when he had worse than is unique lists exclusive scoop on it all time, photos and jeff van gundy so protective haus his worst nba Bobcats never forget, modern day and olympians prevailed by childless diners in nba record ever been a better luck to ever? Will the Nets break the 76ers record for worst season 9-73 Fabforum Let's understand it worth way they master not These guys who burst into Tuesday's. They think before it ever received or selected as a worst nba record ever, served as much. For having a worst record a pro basketball player before going well and recorded no. Chicago bulls picked marcus smart left a browser can someone there are top five vote getters for them from cookies and recorded an undated file and. That the player with silver second-worst 3PT ever is Antoine Walker. Worst Records of hope Top 10 NBA Players Who Ever Played. Not to watch the Magic's 30-35 record would be apparent from the worst we've already in the playoffs Since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976 there have. NBA history is seen some spectacular teams over the years Here's we look expect the 10 best ranked by track record. -

CITY of LYNN, MASSACHUSETTS Annual Financial Statements for the Year Ended June 30, 2007

CITY OF LYNN, MASSACHUSETTS Annual Financial Statements For the Year Ended June 30, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT 1 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 3 BASIC FINANCIAL STATEMENTS: Government-Wide Financial Statements: Statement of Net Assets 18 Statement of Activities 19 Fund Financial Statements: Governmental Funds: Balance Sheet 20 Reconciliation of Total Governmental Fund Balances to Net Assets of Governmental Activities in the Statement of Net Assets 21 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances 22 Reconciliation of the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances of Governmental Funds to the Statement of Activities 23 Statement of Revenues and Other Sources, and Expenditures and Other Uses - Budget and Actual - General Fund 24 Proprietary Funds: Statement of Net Assets 25 Statement of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Fund Net Assets 26 Statement of Cash Flows 27 Fiduciary Funds: Statement of Fiduciary Net Assets 28 Statement of Changes in Fiduciary Net Assets 29 Notes to Financial Statements 30 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Contributory Retirement System Information 54 MH&Co Melanson Heath & Company, PC Certified Public Accountants Management Advisors 10 New England Business Center Drive Suite 112 Andover, MA 01810 Tel (978) 749-0005 Fax (978) 749-0006 www.melansonheath.com INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT To the Mayor and City Council City of Lynn, Massachusetts We have audited the accompanying financial statements of the governmental activi- ties, the business-type activities, each major fund, and the aggregate remaining fund information of the City of Lynn, Massachusetts, as of and for the year ended June 30, 2007 (except for the Lynn Contributory Retirement System which is as of and for the year ended December 31, 2006), which collectively comprise the City’s basic financial statements as listed in the table of contents. -

Unpublished History of the United States Marshals Service (USMS), 1977

Description of document: Unpublished History of the United States Marshals Service (USMS), 1977 Requested date: 2019 Release date: 26-March-2021 Posted date: 12-April-2021 Source of document: FOIA/PA Officer Office of General Counsel, CG-3, 15th Floor Washington, DC 20350-0001 Main: (703) 740-3943 Fax: (703) 740-3979 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. U.S. Department of Justice United States Marshals Service Office of General Counsel CG-3, 15th Floor Washington, DC 20530-0001 March 26, 2021 Re: Freedom of Information Act Request No.