Identifying Shorebirds in British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris Pusilla in Brazil: Occurrence Away from the Coast and a New Record for the Central-West Region

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 27(3): 218–221. SHORT-COMMUNICARTICLEATION September 2019 Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla in Brazil: occurrence away from the coast and a new record for the central-west region Karla Dayane de Lima Pereira1,3 & Jayrson Araújo de Oliveira2 1 Programa Integrado de Estudos da Fauna da Região Centro Oeste do Brasil (FaunaCO), Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 2 Departamento de Morfologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 27 March 2019. Accepted on 16 September 2019. ABSTRACT: The Semipalmated Sandpiper, Calidris pusilla, is a Western Hemisphere migrant shorebird for which Brazil forms an internationally important contranuptial area. In Brazil, the species main contranuptial areas is along the Atlantic Ocean coast, in the north and northeast regions. In addition to these primary contranuptial areas, there are also records of vagrants widely distributed across Brazil. Here, we review the occurrence of vagrants of this species in Brazil, and document a new record of C. pusilla for the central-west region and a first occurrence for the state of Goiás. KEY-WORDS: geographical distribution, Nearctic migrant, shorebird, state of Goiás, vagrant. The Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla (Linnaeus, of Mato Grosso (Cintra 2011, Levatich & Padilha 2019) 1766) is a migratory shorebird species that breeds in and two in the municipality of Corumbá, state of Mato the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Alaska and Canada Grosso do Sul (Serrano 2010, Tubelis & Tomas 2003). (Andres et al. 2012, IUCN 2019). Every year, as the However, there is no evidence that these records have northern autumn approaches, Arctic populations fly been correctly identified, as individuals appear not to from 3000 to 4000 km to South America (Hicklin & have been collected and sent to a scientific collection, nor Gratto-Trevor 2010). -

Field Identification of Smaller Sandpipers Within the Genus <I

Field identification of smaller sandpipers within the genus C/dr/s Richard R. Veit and Lars Jonsson Paintings and line drawings by Lars Jonsson INTRODUCTION the hand, we recommend that the reader threeNearctic species, the Semipalmated refer to the speciesaccounts of Prateret Sandpiper (C. pusilia), the Western HESMALL Calidris sandpipers, affec- al. (1977) or Cramp and Simmons Sandpiper(C. mauri) andthe LeastSand- tionatelyreferred to as "peeps" in (1983). Our conclusionsin this paperare piper (C. minutilla), and four Palearctic North America, and as "stints" in Britain, basedupon our own extensivefield expe- species,the primarilywestern Little Stint haveprovided notoriously thorny identi- rience,which, betweenus, includesfirst- (C. minuta), the easternRufous-necked ficationproblems for many years. The hand familiarity with all sevenspecies. Stint (C. ruficollis), the eastern Long- first comprehensiveefforts to elucidate We also examined specimensin the toed Stint (C. subminuta)and the wide- thepicture were two paperspublished in AmericanMuseum of Natural History, spread Temminck's Stint (C. tem- Brtttsh Birds (Wallace 1974, 1979) in Museumof ComparativeZoology, Los minckii).Four of thesespecies, pusilla, whichthe problem was approached from Angeles County Museum, San Diego mauri, minuta and ruficollis, breed on the Britishperspective of distinguishing Natural History Museum, Louisiana arctictundra and are found during migra- vagrant Nearctic or eastern Palearctic State UniversityMuseum of Zoology, tion in flocksof up to thousandsof -

Age-Related Differences in Ruddy Turnstone Foraging and Aggressive Behavior

AGE-RELATED DIFFERENCES IN RUDDY TURNSTONE FORAGING AND AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR SARAH GROVES ABSTRACT.--Theforaging behavior of fall migrant Ruddy Turnstoneswas studiedon the Mas- sachusettscoast on 2 different substrates,barnacle-covered rocks and sand and weed-litteredflats. Foragingrates differedsignificantly between the 2 substrates.On eachsubstrate the foragingand successrates of adults and juveniles differed significantly while the frequenciesof successwere similarfor both age-classes.The observeddifferences in foragingrates of adultsand juvenilesmay be due to the degreeof refinementof foragingtechniques. Experience in searchingfor and handling prey may be a primary factor accountingfor thesedifferences, and foragingperformance probably improves with age and experience.Alternatively, the differencesmay be due to the presenceof inefficient juveniles that do not survive to adulthood. Both adultsand juveniles in the tall-depressedposture were dominant in aggressiveinteractions much morefrequently than birds in the tall-levelposture. In mixedflocks of foragingadult and juvenile turnstones,the four possibletypes of aggressiveinteractions occurred nonrandomly. Adult over juvenile interactionsoccurred more frequently than expected,and juvenile over adult interac- tions were never seen.A tentative explanationof this phenomenonmay be that juveniles misinter- pret or respondambivalently to messagesconveyed behaviorally by adultsand thusbecome espe- cially vulnerableto aggressionby adults.The transiencyof migrantsmade it unfeasibleto evaluate -

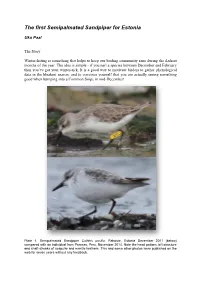

The First Semipalmated Sandpiper for Estonia

The first Semipalmated Sandpiper for Estonia Uku Paal The Story Winter-listing is something that helps to keep our birding community sane during the darkest months of the year. The idea is simple - if you nail a species between December and February then you’ve got your winter-tick. It is a good way to motivate birders to gather phenological data in the bleakest season, and to convince yourself that you are actually seeing something good when bumping into a Common Snipe in mid-December! Plate 1. Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla. Rahuste, Estonia December 2011 (below) compared with an individual from Paracas, Peru, November 2014. Note the head pattern, bill structure and shaft-streaks of scapular and mantle feathers. This and some other photos were published on the web for seven years without any feedback. The late autumn of 2011 looked perfect to get some lingering migrants, as the warm weather was going strong well into January. In the first few days of December, I usually try to get to the west coast in the hope of some lost migrants, and so I packed myself off with Mari and Margus and headed to Saaremaa. Coastal meadows here are often hold a good selection of birds... We start at Türju lighthouse on the 3rd of December with a seawatching session. Nothing shocking this time with the usual Red-throated Divers, Razorbills, and a lone Red-necked Grebe passing. Rahuste coastal meadow is obviously the next site – a well-known place for getting some late birds. The situation looks exceptionally good. After trampling the area for couple of hours we manage to find White Wagtail, Skylark, five Common Snipe, two Pintail, 15 Lapwing, two Common Redshank, Grey Plover and Brant Goose among many other birds. -

Population Analysis and Community Workshop for Far Eastern Curlew Conservation Action in Pantai Cemara, Desa Sungai Cemara – Jambi

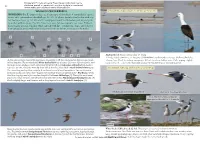

POPULATION ANALYSIS AND COMMUNITY WORKSHOP FOR FAR EASTERN CURLEW CONSERVATION ACTION IN PANTAI CEMARA, DESA SUNGAI CEMARA – JAMBI Final Report Small Grant Fund of the EAAFP Far Eastern Curlew Task Force Iwan Febrianto, Cipto Dwi Handono & Ragil S. Rihadini Jambi, Indonesia 2019 The aim of this project are to Identify the condition of Far Eastern Curlew Population and the remaining potential sites for Far Eastern Curlew stopover in Sumatera, Indonesia and protect the remaining stopover sites for Far Eastern Curlew by educating the government, local people and community around the sites as the effort of reducing the threat of habitat degradation, habitat loss and human disturbance at stopover area. INTRODUCTION The Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariencis) is the largest shorebird in the world and is endemic to East Asian – Australian Flyway. It is one of the Endangered migratory shorebird with estimated global population at 38.000 individual, although a more recent update now estimates the population at 32.000 (Wetland International, 2015 in BirdLife International, 2017). An analysis of monitoring data collected from around Australia and New Zealand (Studds et al. in prep. In BirdLife International, 2017) suggests that the species has declined much more rapidly than was previously thought; with an annual rate of decline of 0.058 equating to a loss of 81.7% over three generations. Habitat loss occuring as a result of development is the most significant threat currently affecting migratory shorebird along the EAAF (Melville et al. 2016 in EAAFP 2017). Loss of habitat at critical stopover sites in the Yellow Sea is suspected to be the key threat to this species and given that it is restricted to East Asian - Australasian Flyway, the declines in the non-breeding are to be representative of the global population. -

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide Large Medium Small 14”-18” 35 - 46 cm 8.5”-12” 22 - 31 cm 6”- 8” 15 - 20 cm Large Shorebirds Medium Shorebirds Small Shorebirds Whimbrel 17.5” 44.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs 9.5” 24 cm Wilson’s Plover 7.75” 19.5 cm Spotted Sandpiper 7.5” 19 cm American Oystercatcher 17.5” 44.5 cm Black-bellied Plover 11.5” 29 cm Sanderling 7.75” 19.5 cm Western Sandpiper 6.5” 16.5 cm Willet 15” 38 cm Short-billed Dowitcher 11” 28 cm White-rumped Sandpiper 6” 15 cm Greater Yellowlegs 14” 35.5 cm Ruddy Turnstone 9.5” 24 cm Semipalmated Sandpiper 6.25” 16 cm 6.25” 16 cm American Avocet* 18” 46 cm Red Knot 10.5” 26.5 cm Snowy Plover Least Sandpiper 6” 15 cm 14” 35.5 cm 8.5” 21.5 cm Semipalmated Plover Black-necked Stilt* Pectoral Sandpiper 7.25” 18.5 cm Killdeer* 10.5” 26.5 cm Piping Plover 7.25” 18.5 cm Stilt Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs & Ruddy Turnstone: Brad Winn; Red Knot: Anthony Levesque; Pectoral Sandpiper & *not pictured Solitary Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm White-rumped Sandpiper: Nick Dorian; All other photos: Walker Golder Clues to help identify shorebirds Size & Shape Bill Length & Shape Foraging Behavior Size Length Sandpipers How big is it compared to other birds? Peeps (Semipalmated, Western, Least) Walk or run with the head down, picking and probing Spotted Sandpiper Short Medium As long Longer as head than head Bobs tail up and down when walking Plovers, Turnstone or standing Small Medium Large Sandpipers White-rumped Sandpiper Tail tips up while probing Yellowlegs Overall Body Shape Stilt Sandpiper Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Probes mud like “oil derrick,” Willet, rear end tips up Dowitcher, Curvature Plovers Stilt, Avocet Run & stop, pick, hiccup, run & stop Elongate Compact Yellowlegs Specific Body Parts Stroll and pick Bill & leg color Straight Upturned Dowitchers Eye size Plovers = larger, sandpipers = smaller Tip slightly Probe mud with “sewing machine” Leg & neck length downcurved Downcurved bill, body stays horizontal . -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

The Systematic Position of the Surfbird, Aphriza Virgata

THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE SURFBIRD, APHRIZA VIRGATA JOSEPH R. JEHL, JR. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 The taxonomic relationships of the Surfbird, ( 1884) elevated the tumstone-Surfbird unit Aphriza virgata, have long been one of the to family rank. But, although they stated (p. most controversial problems in shorebird clas- 126) that Aphrizu “agrees very closely” with sification. Although the species has been as- Arenaria, the only points of similarity men- signed to a monotypic family (Shufeldt 1888; tioned were “robust feet, without trace of web Ridgway 1919), most modern workers agree between toes, the well formed hind toe, and that it should be placed with the turnstones the strong claws; the toes with a lateral margin ( Arenaria spp. ) in the subfamily Arenariinae, forming a broad flat under surface.” These even though they have reached no consensuson differences are hardly sufficient to support the affinities of this subfamily. For example, familial differentiation, or even to suggest Lowe ( 1931), Peters ( 1934), Storer ( 1960), close generic relationship. and Wetmore (1965a) include the Arenariinae Coues (1884605) was uncertain about the in the Scolopacidae (sandpipers), whereas Surfbirds’ relationships. He called it “a re- Wetmore (1951) and the American Ornithol- markable isolated form, perhaps a plover and ogists ’ Union (1957) place it in the Charadri- connecting this family with the next [Haema- idae (plovers). The reasons for these diverg- topodidae] by close relationships with Strep- ent views have never been stated. However, it silas [Armaria], but with the hind toe as well seems that those assigning the Arenariinae to developed as usual in Sandpipers, and general the Charadriidae have relied heavily on their appearance rather sandpiper-like than plover- views of tumstone relationships, because schol- like. -

Purple Sandpiper

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Calidris maritima (Purple Sandpiper) Priority 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Scolopacidae (Curlews, Dowitchers, Godwits, Knots, Phalaropes, Sandpipers, Snipe, Yellowlegs, And Woodcock) General comments: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering population, regional surveys suggest Maine may support over 1/3 of the Western Atlantic wintering population. USFWS Region 5 and Canadian Maritimes winter at least 90% of the Western Atlantic population. Species Conservation Range Maps for Purple Sandpiper: Town Map: Calidris maritima_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Calidris maritima_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: Purple Sandpiper is currently undergoing steep population declines, which has already led to, or if unchecked is likely to lead to, local extinction and/or range contraction. Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering populat Regional Endemic: Calidris maritima's global geographic range is at least 90% contained within the area defined by USFWS Region 5, the Canadian Maritime Provinces, and southeastern Quebec (south of the St. Lawrence River). Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Biogeographical Profiles of Shorebird Migration in Midcontinental North America

U.S. Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Technical Report Series Information and Biological Science Reports ISSN 1081-292X Technology Reports ISSN 1081-2911 Papers published in this series record the significant find These reports are intended for the publication of book ings resulting from USGS/BRD-sponsored and cospon length-monographs; synthesis documents; compilations sored research programs. They may include extensive data of conference and workshop papers; important planning or theoretical analyses. These papers are the in-house coun and reference materials such as strategic plans, standard terpart to peer-reviewed journal articles, but with less strin operating procedures, protocols, handbooks, and manu gent restrictions on length, tables, or raw data, for example. als; and data compilations such as tables and bibliogra We encourage authors to publish their fmdings in the most phies. Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review appropriate journal possible. However, the Biological Sci and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. ence Reports represent an outlet in which BRD authors may publish papers that are difficult to publish elsewhere due to the formatting and length restrictions of journals. At the same time, papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. To purchase this report, contact the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161 (call toll free 1-800-553-684 7), or the Defense Technical Infonnation Center, 8725 Kingman Rd., Suite 0944, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060-6218. Biogeographical files o Shorebird Migration · Midcontinental Biological Science USGS/BRD/BSR--2000-0003 December 1 By Susan K. -

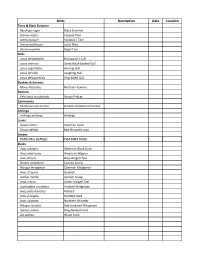

Bird Species Check List

Birds Description Date Location Terns & Black Skimmer Rynchops niger Black Skimmer Sterna caspia Caspian Tern Stema forsteri Forester's Tern Sterna antillarum Least Tern Sterna maxima Royal Tern Gulls Larus philadelphia Bonaparte's Gull Larus marinus Great Black‐backed Gull Larus argentatus Herring Gull Larus atricilla Laughing Gull Larus delawarensis Ring‐billed Gull Boobies & Gannets Morus bassanus Northern Gannet Pelicans Pelecanus occidentalis Brown Pelican Cormorants Phalacrocorax auritus Double‐Crested Cormorant Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Anhinga Loons Gavia immer Common Loon Gavia stellata Red‐throated Loon Grebes PodilymbusPodil ymbus popodicepsdiceps PiPieded‐billbilleded GrebeGrebe Ducks Anas rubripes American Black Duck Anas americana American Wigeon Anas discors Blue‐winged Teal Branta canadensis Canada Goose Mergus merganser Common Merganser Anas strepera Gadwall Aythya marila Greater Scaup Anas crecca Green‐winged Teal Lophodytes cucullatus Hooded Merganser Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Anas fulvigula Mottled Duck Anas clypeata Northern Shoveler Mergus serrator Red‐breasted Merganser Aythya collaris Ring‐Necked Duck Aix sponsa Wood Duck Birds Description Date Location Rails & Northern Jacana Fulica americana American Coot Rallus longirostris Clapper Rail Gallinula chloropus Common Moorhen Rallus elegans King Rail Porzana carolina Sora Long‐legged Waders Nycticorax nycticorax Black‐crowned Night‐Heron Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret Plegadis falcinellus Glossy Ibis Ardea herodias Great Blue Heron Casmerodius albus Great Egret Butorides