Age-Related Differences in Ruddy Turnstone Foraging and Aggressive Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Analysis and Community Workshop for Far Eastern Curlew Conservation Action in Pantai Cemara, Desa Sungai Cemara – Jambi

POPULATION ANALYSIS AND COMMUNITY WORKSHOP FOR FAR EASTERN CURLEW CONSERVATION ACTION IN PANTAI CEMARA, DESA SUNGAI CEMARA – JAMBI Final Report Small Grant Fund of the EAAFP Far Eastern Curlew Task Force Iwan Febrianto, Cipto Dwi Handono & Ragil S. Rihadini Jambi, Indonesia 2019 The aim of this project are to Identify the condition of Far Eastern Curlew Population and the remaining potential sites for Far Eastern Curlew stopover in Sumatera, Indonesia and protect the remaining stopover sites for Far Eastern Curlew by educating the government, local people and community around the sites as the effort of reducing the threat of habitat degradation, habitat loss and human disturbance at stopover area. INTRODUCTION The Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariencis) is the largest shorebird in the world and is endemic to East Asian – Australian Flyway. It is one of the Endangered migratory shorebird with estimated global population at 38.000 individual, although a more recent update now estimates the population at 32.000 (Wetland International, 2015 in BirdLife International, 2017). An analysis of monitoring data collected from around Australia and New Zealand (Studds et al. in prep. In BirdLife International, 2017) suggests that the species has declined much more rapidly than was previously thought; with an annual rate of decline of 0.058 equating to a loss of 81.7% over three generations. Habitat loss occuring as a result of development is the most significant threat currently affecting migratory shorebird along the EAAF (Melville et al. 2016 in EAAFP 2017). Loss of habitat at critical stopover sites in the Yellow Sea is suspected to be the key threat to this species and given that it is restricted to East Asian - Australasian Flyway, the declines in the non-breeding are to be representative of the global population. -

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide Large Medium Small 14”-18” 35 - 46 cm 8.5”-12” 22 - 31 cm 6”- 8” 15 - 20 cm Large Shorebirds Medium Shorebirds Small Shorebirds Whimbrel 17.5” 44.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs 9.5” 24 cm Wilson’s Plover 7.75” 19.5 cm Spotted Sandpiper 7.5” 19 cm American Oystercatcher 17.5” 44.5 cm Black-bellied Plover 11.5” 29 cm Sanderling 7.75” 19.5 cm Western Sandpiper 6.5” 16.5 cm Willet 15” 38 cm Short-billed Dowitcher 11” 28 cm White-rumped Sandpiper 6” 15 cm Greater Yellowlegs 14” 35.5 cm Ruddy Turnstone 9.5” 24 cm Semipalmated Sandpiper 6.25” 16 cm 6.25” 16 cm American Avocet* 18” 46 cm Red Knot 10.5” 26.5 cm Snowy Plover Least Sandpiper 6” 15 cm 14” 35.5 cm 8.5” 21.5 cm Semipalmated Plover Black-necked Stilt* Pectoral Sandpiper 7.25” 18.5 cm Killdeer* 10.5” 26.5 cm Piping Plover 7.25” 18.5 cm Stilt Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs & Ruddy Turnstone: Brad Winn; Red Knot: Anthony Levesque; Pectoral Sandpiper & *not pictured Solitary Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm White-rumped Sandpiper: Nick Dorian; All other photos: Walker Golder Clues to help identify shorebirds Size & Shape Bill Length & Shape Foraging Behavior Size Length Sandpipers How big is it compared to other birds? Peeps (Semipalmated, Western, Least) Walk or run with the head down, picking and probing Spotted Sandpiper Short Medium As long Longer as head than head Bobs tail up and down when walking Plovers, Turnstone or standing Small Medium Large Sandpipers White-rumped Sandpiper Tail tips up while probing Yellowlegs Overall Body Shape Stilt Sandpiper Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Probes mud like “oil derrick,” Willet, rear end tips up Dowitcher, Curvature Plovers Stilt, Avocet Run & stop, pick, hiccup, run & stop Elongate Compact Yellowlegs Specific Body Parts Stroll and pick Bill & leg color Straight Upturned Dowitchers Eye size Plovers = larger, sandpipers = smaller Tip slightly Probe mud with “sewing machine” Leg & neck length downcurved Downcurved bill, body stays horizontal . -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

AVIAN PARAMYXOVIRUSES in SHOREBIRDS and Gulls

journal Diseases, 46(2), 2010, pp. 481-487 \Vildlife Disease Association 2010 AVIAN PARAMYXOVIRUSES IN SHOREBIRDS AND GUllS laura l. Coffee,1,5 Britta A. Hanson,' M. Page Luttrell;' David E. Swa~ne,2 Dennis A. Senne,3 Virginia H. Goekjlan," lawrence J. Niles,4,6 and David E. Stallknecht1, 1 Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study, Departrnent of Population Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, USA 2 Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, US Departrnent of Agriculture, Athens, Georgia 30605, USA 3 US Departrnent of Agriculture, Anirnal and Plant Health Inspection Service, National Veterinary Services Laboratories, Ames, Iowa 50010, USA 4 Endangered and Nongame Species Program, New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife, PO Box 400, Trenton, New Jersey 08625, USA 5 Current address: Cornell University, College of Veterinary Medicine, S2-118 Schurman Hall, Biomedical Sciences, Ithaca, New York 14853, USA 6 Current address: Conserve Wildlife Foundation, 516 Farnsworth Avenue, Bordertown, New Jersey 08505, USA 7 Corresponding author (email: [email protected]) ABSTRACT: There are nine serotypes of avian paramyxovirus (APMV), including APMV-1, or Newcastle disease virus. Although free-flying ducks and geese have been extensively monitored for APMV, limited information is available for species in the order Charadriiforrnes. From 2000 to 2005 we tested cloacal swabs from 9,128 shorebirds and gulls (33 species, five families) captured in 10 states within the USA and in three countries in the Caribbean and South America. Avian paramyxoviruses were isolated from 60 (0.7%) samples by inoculation of embryonating chicken eggs; isolates only included APMV-1 and APMV-2. -

The Following Is a List of Birds Seen Or Reported Around Vinalhaven Over the Past Twenty Years

The following is a list of birds seen or reported around Vinalhaven over the past twenty years. Common Loon (Gavia immer) Snipe (Gallinago gallinago) Red-throated Loon (Gavia stellata) Woodcock (Scolopax minor)N Red Necked Grebe Podiceps grisegena) Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres) Horned Grebe (Podiceps auritus) Purple Sandpiper (Calidris maritime) Pie- billed Grebe (Poilymbus podiceps)N? Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Yellow-nosed albatross (Diomedi chlororhynchos) Dunlin (Calidris alpina) Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis) Sanderling (Calidris alba) Sooty Shearwater (Puffinus griseus) Semipalmated Sandpiper (Calidris pusilla) Greater Shearwater (Puffinus gravis) Western Sandpiper (Calidrs mauri) Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus) Least Sandpiper (Calsidris minuttla) Wilson’s Petrel (Oceanites oceanicus) White-rumped Sandpiper (Calidris fuscicollis) Leach’s Petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa)N Baird’s Snadpiper (Calidris bairdii) White Pelican (Pelecanus erthrorhynchos) Pectoral Sandpiper (Calidris melnotos) Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda) Gannet (Sula bassanus) Pomarine Jaeger (Stoecorarius pomarinus) Great Cormorant (Phalocrocorax carbo)N Parasitic Jaeger (Stercorarius parasiticus) Double -breasted cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus)N Little Gull (Larus minutus) Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) Laughing Gull (Larus atricilla)N Bittern (Botaurus lentiginosus) Ring-billed Gull (Larus delawarensis) Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) Herring Gull (Larus argenatatusN Green Heron (Butorides -

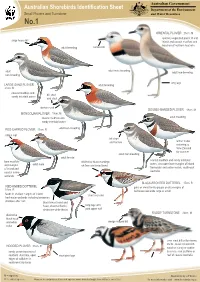

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

Bird Observations in Siriuspasset, North Greenland, 2016 and 2017

Bird observations in Siriuspasset, North Greenland, 2016 and 2017 WON YOUNG LEE (Med et dansk resumé: Fugleobservationer i Siriuspasset, Nordgrønland, 2016 og ’17) Abstract During the summer seasons of 2016 and 2017, bird observations were recorded near Siriuspasset in Nansen Land, North Greenland. Breeding birds were surveyed in a 9 km2 area. Wader populations were dense compared to other sites in North and Northeast Greenland, and Red Phalarope Phalaropus fulicarius and Lapland Longspur Calca- rius lapponicus were found to breed far north of their previously known distributions in Greenland. Introduction Description of the study area and methods During the summers of 2016 and 2017, a Danish-Korean The study site was located on the east shore of J. P. Koch expedition performed biological and paleontological Fjord at the southwestern end of Siriuspasset, at alti- studies near Siriuspasset in Nansen Land, North Green- tudes of 0-300 m a.s.l., and here a well-vegetated area land. Compared to the North Greenland region as a of 9 km2 was censused for breeding birds (Figs 1 & 2). whole, Siriuspasset and its surroundings have very lush This was delimited by the coast, a river and features in vegetation, comparable to areas 900 km to the south in the terrain. Northeast Greenland (cf. Fig. 20 in Aastrup et al. 2005). From 25 July to 13 August, 2016 and 30 June to 21 Siriuspasset is a well-known habitat for both muskoxen July, 2017 breeding birds were monitored daily in the Ovibos moschatus and wolves Canis lupus, and high census area. In both years, the survey periods were actu- numbers of moulting Pink-footed Geese Anser brachyr- ally too late to census breeding waders, as failed breed- rhynchus were recorded there in 2009 during an aerial ers may have left by then (cf. -

Bird Sightings January/February 1997 Summary

BIRD OBSERVER © Barry Van Dusen VOL. 25 NO. 3 JUNE 1997 BIRD OBSERVER • bimonthly journal • To enhance understanding, observation, and enjoyment of birds. Ma S S ^ VOL. 25, NO. 3 JUNE 1997 Editor in Chief Board of Directors Corporate Officers Matthew L. Pelikan Dorothy R. Atvidson President Associate Editor Marjorie W. Rines Alden G. Clayton Janet L. Heywood Treasurer & Clerk Department Heads William E. Davis, Jr. Glenn d’Entremont Assistant Clerk Cover Art H. Christian Floyd John A. Shetterly William E. Davis, Jr. Janet L. Heywood Where to Go Birding Subscription Manager Harriet E. Hoffman Jim Berry Carolyn Marsh Feature Articles Matthew L. Pelikan Advertisements Guy Washburn Marta Hersek Wayne R. Petersen Book Reviews Associate Staff John A. Shetterly Alden G. Clayton Theodore Atkinson Bird Sightings Robert H. Stymeist David E. Lange Robert H. Stymeist Patricia A. O’Neill Simon Perkins At a Glance Pamela A. Perry Wayne R. Petersen BIRD OBSERVER (USPS 369-850) is published bimonthly, COPYRIGHT © 1997 by Bird Observer of Eastern Massachusetts, Inc., 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178, a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation under section 501 (c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Gifts to Bird Observer will be greatly appreciated and are tax deductible. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to BIRD OBSERVER, 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178. PERIODICALS CLASS POSTAGE PAID AT BOSTON, MA. SUBSCRIPTIONS: $21 for 6 issues, $40 for two years in the U.S. Add $2.50 per year for Canada and foreign. Single copies $4.00. An Index to Volumes 1-11 is $3. Back issues: inquire as to price and availability. -

Arenaria Interpres (Ruddy Turnstone)

Arenaria interpres (Ruddy Turnstone) European Red List of Birds Supplementary Material The European Union (EU27) Red List assessments were based principally on the official data reported by EU Member States to the European Commission under Article 12 of the Birds Directive in 2013-14. For the European Red List assessments, similar data were sourced from BirdLife Partners and other collaborating experts in other European countries and territories. For more information, see BirdLife International (2015). Contents Reported national population sizes and trends p. 2 Trend maps of reported national population data p. 4 Sources of reported national population data p. 7 Species factsheet bibliography p. 10 Recommended citation BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Further information http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/euroredlist http://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/european-red-list-birds-0 http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/europe http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ Data requests and feedback To request access to these data in electronic format, provide new information, correct any errors or provide feedback, please email [email protected]. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds Arenaria interpres (Ruddy Turnstone) Table 1. Reported national breeding population size and trends in Europe1. Country (or Population estimate Short-term population -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Biometrics and Breeding Phenology of Terek Sandpipers in the Pripyat’ Valley, S Belarus

54 Wader Study Group Bulletin Biometrics and breeding phenology of Terek Sandpipers in the Pripyat’ Valley, S Belarus NATALIA KARLIONOVA1, MAGDALENA REMISIEWICZ2, PAVEL PINCHUK1 1Institute of Zoology, Belarussian National Academy of Sciences, Academichnaya Str. 27, 220072 Minsk, Belarus. [email protected] 2Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Dept of Vertebrate Ecology and Zoology, Univ. of Gdansk, al. Legionów 9, 80-441 Gdansk, Poland. [email protected] Karlionova, N., Remisiewicz, M. & Pinchuk, P. 2006. Biometrics and breeding phenology of Terek Sandpipers in the Pripyat’ Valley, S Belarus. Wader Study Group Bull. 110: 54–58. Keywords: Terek Sandpiper, Xenus cinereus, biometrics, breeding phenology, Pripyat’ Valley, Belarus We present data on the breeding phenology and biometrics of Terek Sandpipers from the isolated westernmost population in the Pripyat’ river valley, S Belarus, close to the border with Ukraine. Studies were conducted on floodplain islands between the beginning of April and mid-July during 1996–1999 and 2002–2006. Over the years, the first arrivals appeared during 10–26 April (median 14 April), first eggs were laid during 24 April to 5 May (median 30 April) and the latest egg was laid on 25 May, first chicks hatched during 19 May to 1 June (median 25 May) and the first fledged juveniles were caught on 23 June. We present biometric data for juve- niles (at the post-fledging stage) and adults. The mean wing length of juveniles, just before departure from the breeding grounds in mid June, reached 96% of that of adults. Juvenile total head lengths were 91% of adult, and bill and nalospi lengths 85% of adult, but tarsus and tarsus plus toe lengths were the same as adults. -

Guide of Bird Watching Course on Sado Island

Guide of bird watching course on Sado island SPRING Recommended theme: Migratory birds in Washizaki Place: Washizaki cape in northeastern in Sado Birds: Duck, Grebe, Plover, Snipe, Wagtail, etc. -Watch the birds stay and regroup their flocks in Washizaki. List of birds that can be observed on Sado in spring English name Scientific name *Duck etc. Mandarin duck Aix galericulata Gadwall Anas strepera Falcated duck Anas falcata Eurasian Wigeon Anas penelope American Wigeon Anas americana Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Eastern spot-billed duck Anas zonorhyncha Northern shoveler Anas clypeata Northern pintail Anas acuta Garganey Anas querquedula Teal Anas crecca Common pochard Aythya ferina Tufted duck Aythya fuligula Greater scaup Aythya marila Harlequin duck Histrionicus histrionicus Black scoter Melanitta americana Common goldeneye Bucephala clangula Smew Mergellus albellus Common merganser Mergus merganser Red-breasted merganser Mergus serrator *Grebe Little grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis Red-necked grebe Podiceps grisegena Great crested grebe Podiceps cristatus Horned grebe Podiceps auritus Eared grebe Podiceps nigricollis *Plover, Snipe, etc. Northern lapwing Vanellus vanellus Pacific golden-plover Pluvialis fulva Black-bellied plover Pluvialis squatarola Little ringed plover Charadrius dubius 1 Kentish plover Charadrius alexandrinus Lesser sand-plover Charadrius mongolus Black-winged stilt Himantopus himantopus Eurasian woodcock Scolopax rusticola Solitary snipe Gallinago solitaria Latham's snipe Gallinago hardwickii Common snipe Gallinago