JREV3.2Full.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bustersimpson-Surveyor.Pdf

BUSTER SIMPSON // SURVEYOR BUSTER SIMPSON // SURVEYOR FRYE ART MUSEUM 2013 EDITED BY SCOTT LAWRIMORE 6 Foreword 8 Acknowledgments Carol Yinghua Lu 10 A Letter to Buster Simpson Charles Mudede 14 Buster Simpson and a Philosophy of Urban Consciousness Scott Lawrimore 20 The Sky's the Limit 30 Selected Projects 86 Selected Art Master Plans and Proposals Buster Simpson and Scott Lawrimore 88 Rearview Mirror: A Conversation 100 Buster Simpson // Surveyor: Installation Views 118 List of Works 122 Artist Biography 132 Maps and Legends FOREWORD WOODMAN 1974 Seattle 6 In a letter to Buster Simpson published in this volume, renowned Chinese curator and critic Carol Yinghua Lu asks to what extent his practice is dependent on the ideological and social infrastructure of the city and the society in which he works. Her question from afar ruminates on a lack of similar practice in her own country: Is it because China lacks utopian visions associated with the hippie ethos of mid-twentieth-century America? Is it because a utilitarian mentality pervades the social and political context in China? Lu’s meditations on the nature of Buster Simpson’s artistic practice go to the heart of our understanding of his work. Is it utopian? Simpson would suggest it is not: his experience at Woodstock “made me realize that working in a more urban context might be more interesting than this utopian, return-to-nature idea” (p. 91). To understand the nature of Buster Simpson’s practice, we need to accompany him to the underbelly of the city where he has lived and worked for forty years. -

Big Band Arrangers of the Swing Era Selected List

Big Band Arrangers of the Swing Era Selected list Band leader Arrangers Tex Beneke Henry Mancini Jimmy Dorsey Tutti Camarata Sonny Burke Tommy Dorsey Paul Weston Sy Oliver Axel Stordahl Benny Goodman Eddie Sauter Buster Harding Fletcher Henderson Horace Heidt Frank DeVol Woody Herman Heil Hefti Ralph Burns Igor Stravinsky Harry James Leroy Holmes Dave Mathews Isham Jones Gordon Jenkins Hal Kemp John Scott Trotter Elliot Lawrence Gerry Mulligan Ray McKinley Eddie Sauter Red Norvo Eddie Sauter Artie Shaw Ray Conniff Johnny Mandel Buster Harding Charlie Spivak Nelson Riddle Claude Thornhill Gil Evans Leader/Arranger Arranger Count Basie Buster Smith Jimmy Mundy Andy Gibson Herschel Evans Cab Calloway Foots Thomas Harry White Duke Ellington Billy Strayhorn Earl Hines Jimmy Mundy Budd Johnson Stan Kenton Pete Rugolo Bill Holman Andy Kirk Mary Lou Williams Earl Thompson Glen Miller Bill Finegan Billy May Claude Thornhill Gil Evans Bill Borden Gerry Mulligan Chick Webb Edgar Sampson Charlie Dixon Andy Gibson Herschel Evans Leader/Arranger Les Brown Benny Carter Larry Clinton Will Hudson Elliot Lawrence Russ Morgan Ray Noble Boyd Raeburn Raymond Scott Musicians in Bands that were Important Arrangers Leader Arranger Instrument Bob Crosby Bob Haggart bass Matty Matlock saxophone Deane Kincaide saxophone Jimmy Dorsey Tutti Camarata trumpet Joe Lipman piano Woody Herman Heil Hefti trumpet Ralph Burns piano Hal Kemp John Scott Trotter piano Gene Krupa Gerry Mulligan saxophone Jimmy Lunceford Sy Oliver trumpet Glen Miller Henry Mancini piano Artie Shaw Ray Conniff trombone Johnny Mandel trombone Charlie Spivak Nelson Riddle trombone . -

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic “When Johnny Cash comes on the radio, no one changes the station. It’s a voice, a name with a soul that cuts across all boundaries and it’s a voice we all believe. Yours is a voice that speaks for the saints and the sinners – it’s like branch water for the soul. Long may you sing out. Loud.” – Tom Waits audio int‘l p. o. box 560 229 60407 frankfurt/m. germany www.audio-intl.com Catalog: IMP 6008 Format: 180-gram LP tel: 49-69-503570 mobile: 49-170-8565465 Available Spring 2011 fax: 49-69-504733 To order/preorder, please contact your favorite audiophile dealer. Jennifer Warnes, Famous Blue Raincoat. Shout-Cisco (three 200g 45rpm LPs). Joan Baez, In Concert. Vanguard-Cisco (180g LP). The 20th Anniversary reissue of Warnes’ stunning Now-iconic performances, recorded live at college renditions from the songbook of Leonard Cohen. concerts throughout 1961-62. The Cisco 45 rpm LPs define the state of the art in vinyl playback. Holly Cole, Temptation. Classic Records (LP). The distinctive Canadian songstress and her loyal Jennifer Warnes, The Hunter. combo in smoky, jazz-fired takes on the songs of Private-Cisco (200g LP). Tom Waits. Warnes’ post-Famous Blue Raincoat release that also showcases her own vivid songwriting talents in an Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Déjá Vu. exquisite performance and recording. Atlantic-Classic (200g LP). A classic: Great songs, great performances, Doc Watson, Home Again. Vanguard-Cisco great sound. The best country guitar-picker of his day plays folk ballads, bluegrass, and gospel classics. -

Musica Jazz Autore Titolo Ubicazione

MUSICA JAZZ AUTORE TITOLO UBICAZIONE AA.VV. Blues for Dummies MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. \The \\metronomes MSJ/CD MET AA.VV. Beat & Be Bop MSJ/CD BEA AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Victor Jazz History vol. 13 MSJ/CD VIC AA.VV. Blue'60s MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. 8 Bold Souls MSJ/CD EIG AA.VV. Original Mambo Kings (The) MSJ/CD MAM AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 1 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. New Orleans MSJ/CD NEW AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 2 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. \Le \\grandi trombe del Jazz MSJ/CD GRA AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion two (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe III: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI AA.VV. Celebrating the music of Weather Report MSJ/CD CEL AA.VV. Night and Day : The Cole Porter Songbook MSJ/CD NIG AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe II: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball Adderley MSJ/CD ADD Aires Tango Origenes [CD] MSJ/CD AIR Al Caiola Serenade In Blue MSJ/CD ALC Allison, Mose Jazz Profile MSJ/CD ALL Allison, Mose Greatest Hits MSJ/CD ALL Allyson, Karrin Footprints MSJ/CD ALL Anikulapo Kuti, Fela Teacher dont't teach me nonsense MSJ/CD ANI Armstrong, Louis Louis In New York MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Louis Armstrong live in Europe MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Satchmo MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis -

Art Pepper a Taste of Pepper Mp3, Flac, Wma

Art Pepper A Taste Of Pepper mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: A Taste Of Pepper Country: Europe Released: 2010 Style: Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1175 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1614 mb WMA version RAR size: 1715 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 650 Other Formats: VOC WMA AC3 AAC MIDI AIFF MPC Tracklist Hide Credits Art Pepper Meets The Rhythm Section ( 1957 ) You'd Be So Nice To Come Home To 1-1 5:29 Composed By – C. Porter* Red Pepper Blues 1-2 3:41 Composed By – R. Garland* Imagination 1-3 5:55 Composed By – J. Van Heusen And J. Burke* Waltz Me Blues 1-4 3:00 Composed By – A. Pepper*, P. Chambers* Straight Life 1-5 4:02 Composed By – A. Pepper* Jazz Me Blues 1-6 4:50 Composed By – T. Delaney* Tin Tin Deo 1-7 7:45 Composed By – C. Pozo*, G. Fuller* Star Eyes 1-8 5:16 Composed By – D. Raye*, G. DePaul* Birks Works 1-9 4:20 Composed By – D. Gillespie* Mucho Calor ( 1958 ) Mucho Calor 2-1 6:55 Arranged By – Bill HolmanComposed By – B. Holman* Autumn Leaves 2-2 Arranged By – Benny CarterComposed By – G. Parsons*, J. Prévert*, J. 3:07 Mercer*, J. Kosma* Mambo De La Pinta 2-3 5:30 Arranged By – Art PepperComposed By – A. Pepper* I'll Remember April 2-4 2:22 Arranged By – Art PepperComposed By – D. Raye*, G. DePaul*, P. Johnston* Vaya Hombre Vaya 2-5 3:23 Arranged By – Bill HolmanComposed By – B. Holman* I Love You 2-6 5:49 Arranged By – Bill HolmanComposed By – C. -

Fenway Challenge in the North End Concert Series Wraps Up! by Cristina Romano

VOL. 112 - NO. 33 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, AUGUST 22, 2008 $.30 A COPY 2008 Dorothy Curran Fenway Challenge in the North End Concert Series Wraps Up! by Cristina Romano Jackie Andrews of the North End, Brandon Uy of Brighton, Eli Swab of Charlestown, Anthony Bolger of Charlestown, and Jake Scanlon of Charlestown (front row, left to right) were the winners of the Fenway Challenge, part of Boston Centers for Youth & Families’ (BCYF) annual Sox Talks, held at Puopolo Park in the North End. The Boston Red Sox and Boston Police Activities League sponsor the Fenway Challenge, a skill competition in running, hitting, and throwing for boys and girls, ages 6-14. After the challenge, members of the Red Sox Organization arrive and speak with the crowd. Joining the young people in this photo, left to right, are BCYF Director of Recreation A familiar face in the North End, Angelo Picardi of the Ryan Fitzgerald; Red Sox Catcher Kevin Cash; Red Sox First Base Coach DeMarlo Boston Parks and Recreation Department’s ParkARTS Hale; Red Sox Pitching Coach John Farrell; Red Sox Pitcher Javier Lopez; Red Sox staff brought down the house when he was asked to Bullpen Coach Gary Tuck; Red Sox First Base Coach Luis Alicea; Red Sox Pitcher perform during the final show of the 2008 Dorothy David Aardsma; and Red Sox Bench Coach Brad Mills. Curran Wednesday night concerts on August 13th with the US Air Force Band of Liberty and special guest artist Instead of sitting in front of the excitement was evident theme of the day stressed by Crystal Gayle. -

Downbeat.Com March 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. DOWNBEAT.COM MARCH 2014 D O W N B E AT DIANNE REEVES /// LOU DONALDSON /// GEORGE COLLIGAN /// CRAIG HANDY /// JAZZ CAMP GUIDE MARCH 2014 March 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Kathleen Costanza Design Intern LoriAnne Nelson ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene -

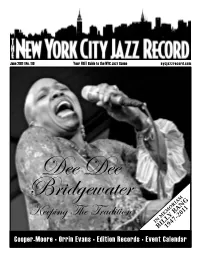

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Robert Glasper's In

’s ION T T R ESSION ER CLASS S T RO Wynton Marsalis Wayne Wallace Kirk Garrison TRANSCRIP MAS P Brass School » Orbert Davis’ Mission David Hazeltine BLINDFOLD TES » » T GLASPE R JAZZ WAKE-UP CALL JAZZ WAKE-UP ROBE SLAP £3.50 £3.50 U.K. T.COM A Wes Montgomery Christian McBride Wadada Leo Smith Wadada Montgomery Wes Christian McBride DOWNBE APRIL 2012 DOWNBEAT ROBERT GLASPER // WES MONTGOMERY // WADADA LEO SmITH // OrbERT DAVIS // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2012 APRIL 2012 VOLume 79 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

20Questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker

20questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker If Benny Goodman was the “King of Swing” periodically to continue his studies over the B-Town and Edward Kennedy Ellington was “the Duke,” next decade, leading a renowned IU-based then David Baker could be called “the Dean big band while expanding his artistic and Hero and Jazz of Jazz.” Distinguished Professor of Music at compositional horizons with musical scholars Indiana University and conductor of the Smithso- such as George Russell and Gunther Schuller. nian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, he is at home In 1966 he settled in the city for good and Legend performing in concert halls, traveling around the began what is now a world-renowned jazz world, or playing in late-night jazz bars. studies program at IU’s Jacobs School of Music. Born in Indianapolis in 1931, he grew up A pioneer of jazz education, a superlative in a thriving mid-20th-century local jazz scene trombonist forced in his early 30s to switch that begat greats such as J.J. Johnson and Wes to cello, a prolific composer, Pulitzer and Montgomery. Baker first came to Bloomington Grammy nominee and Emmy winner whose as a student in the fall of 1949, returning numerous other honors include the Kennedy 56 Bloom | August/September 2007 Toddler David in Indianapolis, circa 1933. Photo courtesy of the Baker family Center for the Performing Arts “Living Jazz Legend Award,” he performs periodically in Bloomington with his wife Lida and is unstintingly generous with the precious commodity of his time. -

Pl | En Strona Główna Muzyka Listy/Porady Nowości Hyde Park

pl | en strona główna muzyka listy/porady nowości hyde park archiwum kontakt SZUKAJ Przedwzmacniacz liniowy Tenor Audio LINE 1/POWER 1 Producent: Tenor Audio Cena: 245 000 zł Kontakt: 17 Willow Bay Drive | Midhurst, ON L0L 1X1 Canada [email protected] www.tenoraudio.com MADE IN CANADA Do testu dostarczyła: SOUNDCLUB enor Audio, maleńka, kanadyjska manufaktura, mająca w Muzyka w tym wydaniu jest dobra, jest aksamitna i ma potężne swojej ofercie zaledwie kilka produktów, znana jest wsparcie na dole pasma. Nie słychać pojedynczych instrumentów, przede wszystkim ze swoich hybrydowych wzmacniaczy, a tylko to, jak korelują z innymi. Wokale nagle pojawiają się przed z tranzystorową końcówka pracującą jako wtórnik prądowy (o nami i gdyby nie to, że zaraz wchodzi niebywale dobrze wzmocnieniu = 1) i lampowym stopniem sterującym. Jej historia różnicowany, mocny bas, zostalibyśmy w stuporze. zaczęła się jednak od zupełnie innych konstrukcji: wzmacniaczy Rozdzielczość, podobnie jak selektywność, nie wydaje się zbyt lampowych OTL, tj. bez transformatorów wyjściowych („output wysoka. O ile z selektywnością to prawda, przedwzmacniacz transformerless”). Jak w wywiadzie udzielonym Mike’owi bazuje na różnicowaniu barw, a nie na „rysowaniu” brył, o tyle z Malinowskiemu wspomina François Lemay, szef sprzedaży, rozdzielczością – nie. To cecha, która charakteryzuje ilość zaczęło się niewinnie, od spotkania z Robertem Lamarre w 1998 informacji, którą dostajemy. Nie „szczegółów”, to co innego niż roku w czasie wystawy audio w Montrealu (cały wywiad TUTAJ). detaliczność. Rozdzielczość to gęstość i naturalność, ciepło i Lamarre wystawiał tam swoje kolumny. Sześć miesięcy później „flow”. Tenor to wszystko ma w nadmiarze. okazało się, że mieszka on kilka ulic od Lemaya – fortunny zbieg Jego prezentacja skupia się na „tu i teraz”.