Bustersimpson-Surveyor.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Link Initial Segment and Airport Link Before & After Study

Central Link Initial Segment and Airport Link Before & After Study Final Report February 2014 (this page left blank intentionally) Initial Segment and Airport Link Before and After Study – Final Report (Feb 2014) Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 Before and After Study Requirement and Purposes ................................................................................................... 1 Project Characteristics ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Milestones .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Data Collection in the Fall .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Organization of the Report ........................................................................................................................................ 2 History of Project Planning and Development ....................................................................................................... 2 Characteristic 1 - Project Scope .............................................................................................................................. 6 Characteristic -

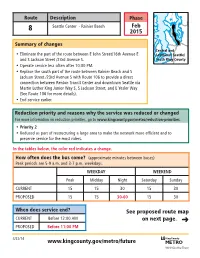

Changes to #8

Route Description Phase Seattle Center - Rainier Beach Feb 8 2015 Summary of changes Central and • Eliminate the part of the route between E John Street/16th Avenue E Southeast Seattle/ and S Jackson Street /23rd Avenue S. South King County • Operate service less often after 10:00 PM. Central/Southeast Seattle • Replace the south part of the route between Rainier Beach and S Jackson Street /23rd Avenue S with Route 106 to provide a direct connection between Renton Transit Center and downtown Seattle via Martin Luther King Junior Way S, S Jackson Street, and E Yesler Way (See Route 106 for more details). • End service earlier. Reduction priority and reasons why the service was reduced or changed For more information on reduction priorities, go to www.kingcounty.gov/metro/reduction-priorities. • Priority 2 • Reduced as part of restructuring a large area to make the network more efficient and to preserve service for the most riders. In the tables below, the color red indicates a change. How often does the bus come? (approximate minutes between buses) Peak periods are 5-9 a.m. and 3-7 p.m. weekdays. Weekday Weekend Peak Midday Night Saturday Sunday CURRENT 15 15 30 15 30 PROPOSED 15 15 30-60 15 30 When does service end? See proposed route map CURRENT Before 12:00 AM on next page. ➜ PROPOSED Before 11:00 PM 4/22/14 www.kingcounty.gov/metro/future Route Description 8 Seattle Center - Rainier Beach Queen Anne E Roy St ve Rider options A Mercer St th 1 5 s 1 t A v St e d N ay E Thomas St E John St • In Capitol Hill Broa Denny Way E Olive W between 16th Avenue n St iso d y a E Ma ve E and 23rd Avenue E, Bore A Jr W rd g n 3 in A 2 use Route 43. -

Central Link Station Boardings, Service Change F

Central Link light rail Weekday Station Activity October 2nd, 2010 to February 4th, 2011 (Service Change Period F) Northbound Southbound Total Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Westlake Station 0 4,108 4,465 0 4,465 4,108 University Street Station 106 1,562 1,485 96 1,591 1,658 Pioneer Square Station 225 1,253 1,208 223 1,433 1,476 International District/Chinatown Station 765 1,328 1,121 820 1,887 2,148 Stadium Station 176 201 198 242 374 443 SODO Station 331 312 313 327 645 639 Beacon Hill Station 831 379 400 958 1,230 1,337 Mount Baker Station 699 526 549 655 1,249 1,180 Columbia City Station 838 230 228 815 1,066 1,045 Othello Station 867 266 284 887 1,151 1,153 Rainier Beach Station 742 234 211 737 952 971 Tukwila/International Blvd Station 1,559 279 255 1,777 1,814 2,055 SeaTac/Airport Station 3,538 0 0 3,181 3,538 3,181 Total 10,678 10,718 21,395 Central Link light rail Saturday Station Activity October 2nd, 2010 to February 4th, 2011 (Service Change Period F) Northbound Southbound Total Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Westlake Station 0 3,124 3,046 0 3,046 3,124 University Street Station 54 788 696 55 750 843 Pioneer Square Station 126 495 424 136 550 631 International District/Chinatown Station 412 749 640 392 1,052 1,141 Stadium Station 156 320 208 187 364 506 SODO Station 141 165 148 147 290 311 Beacon Hill Station 499 230 203 508 702 738 Mount Baker Station 349 267 240 286 588 553 Columbia City Station 483 181 168 412 651 593 Othello Station 486 218 235 461 721 679 -

The Artists' View of Seattle

WHERE DOES SEATTLE’S CREATIVE COMMUNITY GO FOR INSPIRATION? Allow us to introduce some of our city’s resident artists, who share with you, in their own words, some of their favorite places and why they choose to make Seattle their home. Known as one of the nation’s cultural centers, Seattle has more arts-related businesses and organizations per capita than any other metropolitan area in the United States, according to a recent study by Americans for the Arts. Our city pulses with the creative energies of thousands of artists who call this their home. In this guide, twenty-four painters, sculptors, writers, poets, dancers, photographers, glass artists, musicians, filmmakers, actors and more tell you about their favorite places and experiences. James Turrell’s Light Reign, Henry Art Gallery ©Lara Swimmer 2 3 BYRON AU YONG Composer WOULD YOU SHARE SOME SPECIAL CHILDHOOD MEMORIES ABOUT WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO SEATTLE? GROWING UP IN SEATTLE? I moved into my particular building because it’s across the street from Uptown I performed in musical theater as a kid at a venue in the Seattle Center. I was Espresso. One of the real draws of Seattle for me was the quality of the coffee, I nine years old, and I got paid! I did all kinds of shows, and I also performed with must say. the Civic Light Opera. I was also in the Northwest Boy Choir and we sang this Northwest Medley, and there was a song to Ivar’s restaurant in it. When I was HOW DOES BEING A NON-DRIVER IMPACT YOUR VIEW OF THE CITY? growing up, Ivar’s had spokespeople who were dressed up in clam costumes with My favorite part about walking is that you come across things that you would pass black leggings. -

Teresita Fernández

TERESITA FERNÁNDEZ Born Miami, FL, 1968 Lives Brooklyn, NY EDUCATION 1992 MFA, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 1990 BFA, Florida International University, Miami, FL HONORS AND DISTINCTIONS 2017 National Academician, National Academy Museum & School, New York, NY Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers, New York, NY The Drawing Center 40th Anniversary Honoree, New York, NY 2016 Visionary Artist Honoree, Art in General, New York, NY 2013 Aspen Award for Art, The Aspen Art Museum, Aspen, CO 2011 Presidential Appointment to the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (served until 2014) 2005 MacArthur Foundation Fellowship 2003 Guggenheim Fellowship, New York, NY 1999 Louis Comfort Tiffany Biennial Award American Academy in Rome, Affiliated Fellowship 1995 National Foundation for Advancement in the Arts, CAVA Fellowship Metro-Dade Cultural Consortium Grant 1994 NEA Individual Artist's Grant, Visual Arts Cintas Fellowship COMMISSIONS AND SPECIAL PROJECTS 2019 Night Writing, Park Tower at Transbay, San Francisco, CA New Orleans Museum of Art Commission, New Orleans, LA 2015 Double Glass River, Grace Farms, New Canaan, CT Fata Morgana, Madison Square Park, New York, NY* 2014 Golden (Panorama), Aspen Art Museum, Elk Camp, Aspen, CO 2013 Nocturnal (Navigation), United States Coast Guard, Washington, D.C. 2012 Yellow Mountains, Louis Vuitton Shanghai, Shanghai, China Ink Sky, Louis Vuitton Place Vendôme, Paris, France 2010 Angel Building Commission, London, United Kingdom Louis Vuitton Commission, Biennale des Antiquaries, -

On the Edge Nceca Seattle 2012 Exhibition Guide

ON THE EDGE NCECA SEATTLE 2012 EXHIBITION GUIDE There are over 190 exhibitions in the region mounted to coincide with the NCECA conference. We offer excursions, shuttles, and coordinated openings by neighborhood, where possible. Read this document on line or print it out. It is dense with information and we hope it will make your experience in Seattle fulfilling. Questions: [email protected] NCECA Shuttles and Excursions Consider booking excursions or shuttles to explore 2012 NCECA Exhibitions throughout the Seattle region. Excursions are guided and participants ride one bus with a group and leader and make many short stops. Day Dep. Ret. Time Destination/ Route Departure Point Price Time Tue, Mar 27 8:30 am 5:30 pm Tacoma Sheraton Seattle (Union Street side) $99 Tue, Mar 27 8:30 am 5:30 pm Bellingham Sheraton Seattle (Union Street side) $99 Tue, Mar 27 2:00 pm 7:00 pm Bellevue & Kirkland Convention Center $59 Wed, Mar 28 9:00 am 12:45 pm Northwest Seattle Convention Center $39 Wed, Mar 28 1:30 pm 6:15 pm Northeast Seattle Convention Center $39 Wed, Mar 28 9:00 am 6:15 pm Northwest/Northeast Seattle Convention Center $69 combo ticket *All* excursion tickets must be purchased in advance by Tuesday, March 13. Excursions with fewer than 15 riders booked may be cancelled. If cancelled, those holding reservations will be offered their choice of a refund or transfer to another excursion. Overview of shuttles to NCECA exhibitions and CIE openings Shuttles drive planned routes stopping at individual venues or central points in gallery dense areas. -

Buster – Ein Gauner Mit Herz Phil Collins

HanseSound – Exklusiv Titel Buster – Ein Gauner mit Herz Phil Collins • Originaltitel: Buster • Produktionsjahr: 1988 • Produktionsland: Großbritannien • Darsteller: Phil Collins, Julie Walters, Larry Lamb • Regisseur: David Green • Format: Dolby Digital 5.1 (deutsch, englisch), PAL, Breitbild • Region: Region B/2 • Bildseitenformat: 1,66:1 • FSK: Freigegeben ab 12 Jahren • Bonus: englische Fassung mit 102,41 Min.(BD), Anwahl der Musikstücke. deutsche Untertitel MediaBook: DVD & Blu ray DVD: Blu ray: EAN: 4250124370893 EAN: EAN: Vö.: 18.09.2020 Vö.: Vö.: HAP: 14,85 HAP: HAP: Laufzeit:. 96,18+100,10 Laufzeit: 96,18 min. Laufzeit: 100,10 min. Das Wichtigste für den Kleinganoven Buster Edwards (Phil Collins) ist die Liebe seiner Frau June (Julie Walters, „Harry Potter“-Filmreihe). Als diese sich ein Haus wünscht, weiß Buster, dass er ein größeres Ding drehen muss. Mit einigen Kumpanen raubt er einen Postzug aus, doch der ausgetüftelte Plan für danach geht gründlich schief und Buster muss am Ende eine schwere Entscheidung treffen… Die Legende um den berühmtesten Postraub aller Zeiten aus völlig neuer Sicht, garniert mit Welthits aus der Feder von Megastar Phil Collins, der auch die Hauptrolle spielt! Es ist die Tragikomödie aus dem Jahr 1988. Die von Phil Collins gesungene Filmmusik wurde zu einem Erfolg in den Hitparaden. Der Film handelt von dem Postzugräuber Ronald Buster Edwards, von seiner Vorgeschichte, dem Raub und der Flucht nach Mexiko bis hin zur Entlassung aus dem Gefängnis. HanseSound – Exklusiv Titel Die Phil-Collins-Singles aus dem Film, A Groovy Kind of Love und Two Hearts, erreichten Platz 1 und Platz 6 in den UK Singles Charts. -

WATERFRONT Photographic Interlayer

• 61, 64 67 Seattle Cloud Cover, DENNY WAY Myrtle Teresita Fernández, 2006. Edwards Park Laminated glass wall with C1 WATERFRONT photographic interlayer. Seattle Art Museum BAY ST Collection. ON RAILROAD OVERPASS. • 63 MYRTLE EDWARDS PARK WATERFRONT, NORTH OF BAY STREET. • 62 EAGLE ST 68 Father and Son, Louise Olympic 61 Undercurrents, Laura 64 Adjacent, Against, Sculpture Bourgeois, 2005. Stainless Park Haddad and Tom Drugan, Upon, Michael Heizer, steel and aluminum • 67 BROAD ST 2003. Stainless steel, concrete, 1976. Concrete and granite • 66 • 65 fountain and bronze • 68 stone and landscaping. King sculpture. bell. Seattle Art Museum County Public Art Collection CLAY ST Collection. ALASKAN WAY AND (4Culture). BROAD STREET. CEDAR ST BELL STREET PIER VINE ST 69 Bell Harbor Beacon, Ron Fischer, 1996. Painted steel WALL ST and light sculpture. Port of Seattle Art Collection. BELL ST ALASKAN WAY BETWEEN LENORA AND VIRGINIA STREETS. BLANCHARD ST SEATTLE AQUARIUM ALASKAN WAY PIER 59 AND PIER 60. 70 The Wave Wall, Susan Zoccola, 2007. White paneling. Seattle Parks LENORA ST PHOTO: MICHAEL HEIZER. and Recreation Collection. RECEPTION AND FOYER. SEATTLE ART MUSEUM, OLYMPIC SCULPTURE PARK 69 • VIRGINIA ST 2901 WESTERN AVE. SELECTED ARTWORKS AT LOCATION. WATERFRONT PARK ALASKAN WAY AND UNION STREET. 62 Eagle, Alexander Calder, 65 Neukom Vivarium, Mark 1971. Dion, 2006. Painted steel sculpture. Mixed-media 71 Waterfront Fountain, Seattle Art Museum Collection. WATERFRONT installation and custom James Fitzgerald and Z-PATH BETWEEN NORTH AND WEST greenhouse. Seattle Art 1974. MEADOWS. Margaret Tompkins, Museum Collection. ELLIOTT AVE. Seattle 74 Aquarium • AND BROAD STREET. Bronze fountain. • 70 PIKE ST 63 Wake, Richard Serra, 2004. -

RADIO's DIGITAL DILEMMA: BROADCASTING in the 21St

RADIO’S DIGITAL DILEMMA: BROADCASTING IN THE 21st CENTURY BY JOHN NATHAN ANDERSON DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2011 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor John C. Nerone, Chair and Director of Research Associate Professor Michelle Renee Nelson Associate Professor Christian Edward Sandvig Professor Daniel Toby Schiller ii ABSTRACT The interaction of policy and technological development in the era of “convergence” is messy and fraught with contradictions. The best expression of this condition is found in the story behind the development and proliferation of digital audio broadcasting (DAB). Radio is the last of the traditional mass media to navigate the convergence phenomenon; convergence itself has an inherently disruptive effect on traditional media forms. However, in the case of radio, this disruption is mostly self-induced through the cultivation of communications policies which thwart innovation. A dramaturgical analysis of digital radio’s technological and policy development reveals that the industry’s preferred mode of navigating the convergence phenomenon is not designed to provide the medium with a realistically useful path into a 21st century convergent media environment. Instead, the diffusion of “HD Radio” is a blocking mechanism proffered to impede new competition in the terrestrial radio space. HD Radio has several critical shortfalls: it causes interference and degradation to existing analog radio signals; does not have the capability to actually advance the utility of radio beyond extant quality/performance metrics; and is a wholly proprietary technology from transmission to reception. -

Chernow Washington 0250O 1

Disappearing Acts: Making Things + Making Things Go Away Rebecca Chernow A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master's of Fine Arts University of Washington 2014 Committee: Eric Fredricksen Amie McNeel Akio Takamori Mark Zirpel Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Art The world will not evolve past its current state of crisis by using the same thinking that created the situation. --Albert Einstein In a knotted world of vibrant matter, to harm one section of the web may very well be to harm oneself. --Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter Table of Contents Introduction 1 Influences 2 Methodology 4 Concepts 11 Conclusion 18 Works Cited 20 Images 21 Introduction In the text Food of the Gods, Terence McKenna remarks, “our need to feel part of the world seems to demand that we express ourselves through creative activity. The ultimate wellsprings of this creativity are hidden in the mystery of language.” Furthermore, “reality is not simply experienced or reflected in language, but instead is actually produced by language.” Artists are the speakers of a metaphorical language that often takes material form and, as such, develop a vocabulary of material engagement and conceptual embodiment simultaneously. If it is true that, to quote Marshall McLuhan’s famous phrase, “the medium is the message,” then the message is encoded in not only the product, but in the syntax of the production, and the approach to production is reflective of one’s attitude towards life. My over-arching project in graduate school has been to align my creative language with the personal ethics that define how I aim to conduct the rest of my life: to be as direct and natural as possible, to live slowly, simply, and mindfully, and to cultivate a sense of reverence and care for the infinitely complex network of networks that all earthly things are inextricably bound into. -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

The Oceania Cruises Art Collection

THE OCEANIA CRUISES ART CoLLECTION THE OCEANIA CRUISES ART CoLLECTION “I had the same vision and emotional connection in our art acquisitions as I did for Marina and Riviera themselves – to be beautiful, elegant, sophisticated and stylish. The ships and art are one.” – Frank Del Rio 2 | OCEANIA CRUISES ART COLLECTION Introduction In February of 2011, Oceania Cruises unveiled the cruise ship Marina at a gala ceremony in Miami. The elegant new ship represented a long list of firsts: the first ship that the line had built completely from scratch, the first cruise ship suites furnished entirely with the Ralph Lauren Home Collection, and the first custom-designed culinary studio at sea offering hands-on cooking classes. But, one of the most remarkable firsts caught many by surprise. As journalists, travel agents and the first guests explored the decks of the luxurious new vessel, they were astounded to discover that they had boarded a floating art museum, one that showcased a world-class collection of artworks personally curated by the founders of Oceania Cruises. Most cruise lines hire third party contractors to assemble the decorative art for their ships, selecting one of the few companies capable of securing a collection of this scale. The goal of most of these collections is, at best, to enhance the ambiance and, at worst, to simply match the decor. Oceania Cruises founders Frank Del Rio and Bob Binder wanted to take a different approach. “We weren’t just looking for background music,” Binder says. “We wanted pieces that were bold and interesting, pieces that made a statement, provoked conversation and inspired emotion.” Marina and her sister ship, Riviera, were designed to eschew the common look of a cruise ship or hotel.