Seattle Department of Planning & Development IMPLEMENTING TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT in SEATTLE: ASSESSMENT and RECOMMENDATIONS for ACTION TABLE of CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Link Initial Segment and Airport Link Before & After Study

Central Link Initial Segment and Airport Link Before & After Study Final Report February 2014 (this page left blank intentionally) Initial Segment and Airport Link Before and After Study – Final Report (Feb 2014) Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 Before and After Study Requirement and Purposes ................................................................................................... 1 Project Characteristics ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Milestones .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Data Collection in the Fall .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Organization of the Report ........................................................................................................................................ 2 History of Project Planning and Development ....................................................................................................... 2 Characteristic 1 - Project Scope .............................................................................................................................. 6 Characteristic -

Mt. Baker Station Area Transit Oriented Development

ULI TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PANEL REPORT MT. BAKER STATION AREA TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT Northwest Published September 2019 ABOUT ULI NORTHWEST ULI Northwest is a District Council of the Urban Land Institute (ULI), a non- profit education and research organization supported by its members. Founded in 1936, the Institute today has more than 44,000 members worldwide. ULI members represent the full spectrum of land use planning and real estate development disciplines working in the private, public, and non- profit sectors. ULI’s mission is to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. ULI Northwest carries out the ULI mission locally by serving as the preeminent real estate forum in the Pacific Northwest, facilitating the open exchange of ideas, information, and experiences among local, national, and international industry leaders and policy makers. Our mission is to: • Build a regional vision of the Northwest that embraces and acts upon quality growth principles. • Encourage collaboration among all domains—public and private—of the real estate industry. • Build consensus among industry and public leaders who influence land use, transportation, environmental, and economic development policies. Contact Us Northwest ULI Northwest 107 Spring Street Seattle, WA 98104 206.224.4500 [email protected] northwest.uli.org ©2019 ABOUT THE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PANEL (TAP) PROGRAM The ULI Northwest Technical Assistance Panel program brings together a select, independent panel of experts to provide a fresh perspective on complex, local public and private development problems. Panelists represent a variety of professional and academic fields relevant to the issues at hand, including real estate development, planning and design. -

Bustersimpson-Surveyor.Pdf

BUSTER SIMPSON // SURVEYOR BUSTER SIMPSON // SURVEYOR FRYE ART MUSEUM 2013 EDITED BY SCOTT LAWRIMORE 6 Foreword 8 Acknowledgments Carol Yinghua Lu 10 A Letter to Buster Simpson Charles Mudede 14 Buster Simpson and a Philosophy of Urban Consciousness Scott Lawrimore 20 The Sky's the Limit 30 Selected Projects 86 Selected Art Master Plans and Proposals Buster Simpson and Scott Lawrimore 88 Rearview Mirror: A Conversation 100 Buster Simpson // Surveyor: Installation Views 118 List of Works 122 Artist Biography 132 Maps and Legends FOREWORD WOODMAN 1974 Seattle 6 In a letter to Buster Simpson published in this volume, renowned Chinese curator and critic Carol Yinghua Lu asks to what extent his practice is dependent on the ideological and social infrastructure of the city and the society in which he works. Her question from afar ruminates on a lack of similar practice in her own country: Is it because China lacks utopian visions associated with the hippie ethos of mid-twentieth-century America? Is it because a utilitarian mentality pervades the social and political context in China? Lu’s meditations on the nature of Buster Simpson’s artistic practice go to the heart of our understanding of his work. Is it utopian? Simpson would suggest it is not: his experience at Woodstock “made me realize that working in a more urban context might be more interesting than this utopian, return-to-nature idea” (p. 91). To understand the nature of Buster Simpson’s practice, we need to accompany him to the underbelly of the city where he has lived and worked for forty years. -

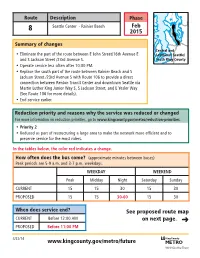

Changes to #8

Route Description Phase Seattle Center - Rainier Beach Feb 8 2015 Summary of changes Central and • Eliminate the part of the route between E John Street/16th Avenue E Southeast Seattle/ and S Jackson Street /23rd Avenue S. South King County • Operate service less often after 10:00 PM. Central/Southeast Seattle • Replace the south part of the route between Rainier Beach and S Jackson Street /23rd Avenue S with Route 106 to provide a direct connection between Renton Transit Center and downtown Seattle via Martin Luther King Junior Way S, S Jackson Street, and E Yesler Way (See Route 106 for more details). • End service earlier. Reduction priority and reasons why the service was reduced or changed For more information on reduction priorities, go to www.kingcounty.gov/metro/reduction-priorities. • Priority 2 • Reduced as part of restructuring a large area to make the network more efficient and to preserve service for the most riders. In the tables below, the color red indicates a change. How often does the bus come? (approximate minutes between buses) Peak periods are 5-9 a.m. and 3-7 p.m. weekdays. Weekday Weekend Peak Midday Night Saturday Sunday CURRENT 15 15 30 15 30 PROPOSED 15 15 30-60 15 30 When does service end? See proposed route map CURRENT Before 12:00 AM on next page. ➜ PROPOSED Before 11:00 PM 4/22/14 www.kingcounty.gov/metro/future Route Description 8 Seattle Center - Rainier Beach Queen Anne E Roy St ve Rider options A Mercer St th 1 5 s 1 t A v St e d N ay E Thomas St E John St • In Capitol Hill Broa Denny Way E Olive W between 16th Avenue n St iso d y a E Ma ve E and 23rd Avenue E, Bore A Jr W rd g n 3 in A 2 use Route 43. -

Central Link Station Boardings, Service Change F

Central Link light rail Weekday Station Activity October 2nd, 2010 to February 4th, 2011 (Service Change Period F) Northbound Southbound Total Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Westlake Station 0 4,108 4,465 0 4,465 4,108 University Street Station 106 1,562 1,485 96 1,591 1,658 Pioneer Square Station 225 1,253 1,208 223 1,433 1,476 International District/Chinatown Station 765 1,328 1,121 820 1,887 2,148 Stadium Station 176 201 198 242 374 443 SODO Station 331 312 313 327 645 639 Beacon Hill Station 831 379 400 958 1,230 1,337 Mount Baker Station 699 526 549 655 1,249 1,180 Columbia City Station 838 230 228 815 1,066 1,045 Othello Station 867 266 284 887 1,151 1,153 Rainier Beach Station 742 234 211 737 952 971 Tukwila/International Blvd Station 1,559 279 255 1,777 1,814 2,055 SeaTac/Airport Station 3,538 0 0 3,181 3,538 3,181 Total 10,678 10,718 21,395 Central Link light rail Saturday Station Activity October 2nd, 2010 to February 4th, 2011 (Service Change Period F) Northbound Southbound Total Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Westlake Station 0 3,124 3,046 0 3,046 3,124 University Street Station 54 788 696 55 750 843 Pioneer Square Station 126 495 424 136 550 631 International District/Chinatown Station 412 749 640 392 1,052 1,141 Stadium Station 156 320 208 187 364 506 SODO Station 141 165 148 147 290 311 Beacon Hill Station 499 230 203 508 702 738 Mount Baker Station 349 267 240 286 588 553 Columbia City Station 483 181 168 412 651 593 Othello Station 486 218 235 461 721 679 -

Sound Transit Climate Risk Reduction Project, F T a Report Number 0075

Sound Transit Climate Risk Reduction Project SEPTEMBER 2013 FTA Report No. 0075 Federal Transit Administration PREPARED BY Lara Whitely Binder, Ingrid Tohver The Climate Impacts Group College of the Environment University of Washington Amy Shatzkin Sound Transit Amy K. Snover The Climate Impacts Group College of the Environment University of Washington COVER PHOTO Photo courtesy of Sound Transit, © 2008 DISCLAIMER This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products of manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Sound Transit Climate Risk Reduction Project SEPTEMBER 2013 FTA Report No. 0075 PREPARED BY Lara Whitely Binder, Ingrid Tohver The Climate Impacts Group College of the Environment University of Washington Amy Shatzkin Sound Transit Amy K. Snover The Climate Impacts Group College of the Environment University of Washington SPONSORED BY Federal Transit Administration Office of Budget and Policy U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 AVAILABLE ONLINE http://www.fta.dot.gov/research Metric Conversion Table SYMBOL WHEN YOU KNOW MULTIPLY BY TO FIND SYMBOL LENGTH in inches 25.4 millimeters mm ft feet 0.305 meters m yd yards 0.914 meters m mi miles 1.61 kilometers km VOLUME fl oz fluid ounces 29.57 milliliters mL gal gallons 3.785 liter L ft3 cubic feet 0.028 cubic meters m3 yd3 cubic yards 0.765 cubic meters m3 NOTE: volumes greater than 1000 L shall be shown in m3 MASS oz ounces 28.35 grams g lb pounds 0.454 kilograms kg megagrams T short tons (2000 lb) 0.907 Mg (or “t”) (or “metric ton”) TEMPERATURE (exact degrees) o 5 (F-32)/9 o F Fahrenheit Celsius C or (F-32)/1.8 FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION ii REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. -

Southeast Transportation Study Final Report

Southeast Transportation Study Final Report Prepared for Seattle Department of Transportation by The Underhill Company LLC in association with Mirai Associates Inc Nakano Associates LLC PB America December 2008 Acknowledgements Core Community Team Pete Lamb, Columbia City Business Association Mayor Gregory J. Nickels Joseph Ayele, Ethiopian Business Association Mar Murillo, Filipino Community of Seattle Denise Gloster, Hillman City Business Association Seattle Department of Transportation Nancy Dulaney, Hillman City Business Association Grace Crunican, Director Pamela Wrenn, Hillman City Neighborhood Alliance Susan Sanchez, Director, Policy and Planning Division Sara Valenta, HomeSight Tracy Krawczyk, Transportation Planning Manager Richard Ranhofer, Lakewood Seward Park Neighborhood Sandra Woods, SETS Project Manager Association Hannah McIntosh, Associate Transportation Planner Pat Murakami, Mt. Baker Community Club Dick Burkhart, Othello Station Community Advisory Board SETS Project Advisory Team Gregory Davis, Rainier Beach Coalition for Community Seattle Department of Transportation Empowerment Barbara Gray, Policy, Planning and Major Projects Dawn Tryborn, Rainier Beach Merchants Association Trevor Partap, Traffi c Management Seanna Jordon, Rainier Beach Neighborhood 2014 John Marek, Traffi c Management Jeremy Valenta, Rainier/Othello Safety Association Peter Lagerway, Traffi c Management Rob Mohn, Rainier Valley Chamber of Commerce Randy Wiger, Parking Thao Tran, Rainier Valley Community Development Fund Dawn Schellenberg, Public -

Meets Special Condition S6 of NPDES Permit

King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks Wastewater Treatment Division King Street Center, KSC-NR-0500 201 South Jackson Street Seattle, WA 98104-3855 February 27, 2018 Biniam Zelelow Washington State Department of Ecology 3190 160th Avenue SE Bellevue, WA 98008-5452 Transmittal of King County Industrial Waste Program's 2017 Annual Pretreatment Report Dear Mr. Zelelow: In accordance with Special Condition S6 of the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permits for the King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks, Wastewater Treatment Division's treatment plants, I am submitting the 2017 Annual Pretreatment Report. This submittal includes an executive summary and a program narrative for 2017, which provides greater detail on program activities. Please find the narrative portion of the report and a CD containing the appendices enclosed with this letter. In addition, the narrative and appendices will be uploaded to the Permitting and Reporting Information System (PARIS). If you have any questions regarding the Annual Pretreatment Report, please call Industrial Waste Program Manager Mark Henley at 206-263-6994 or email him at [email protected]. Sincerely, ^v ~^'-—' Mark Isaacson Division Director Enclosure ec: Chris Townsend, Section Manager, Environmental and Community Services Section (ECSS), Wastewater Treatment Division (WTD), Department of Natural Resources and Parks (DNRP) Mark Henley, Manager, Industrial Waste Program, ECSS, WTD, DNRP Annual Pretreatment Report 2017 March 2018 Department of Natural Resources and Parks Wastewater Treatment Division Industrial Waste Program For comments or questions, contact: Mark Henley King County Wastewater Treatment Division Industrial Waste Program KSC-NR-0513 201 S. Jackson Street Seattle, WA 98104-3855 206-263-6994 [email protected] Alternative Formats Available 206-477-5371, TTY Relay: 711 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... -

King County Lower Duwamish Waterway Source Control Annual Report Year 2017

King County Lower Duwamish Waterway Source Control Annual Report Year 2017 December 2018 This page intentionally left blank King County Lower Duwamish Waterway Source Control Annual Report Year 2017 Prepared for: Washington State Department of Ecology Submitted by: King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks King County Department of Transportation King County Department of Executive Services For more information contact: Debra Williston Water and Land Resources Division King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks 201 S. Jackson St. Seattle, WA 98104-3855 [email protected] This information is available in alternative formats upon request at 206-477-5371 (voice) or 711 (TTY) This page intentionally left blank King County Lower Duwamish Waterway Source Control Annual Report - 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A team of representatives from the King County Wastewater Treatment Division, Water and Land Resources Division, King County International Airport, Roads Services Division, Permitting and Environmental Review, and Local Hazardous Waste Management Program allFacilities contributed Management to the production Division, Public of this Health−Seattle report. The production & King County, was managed Department and of coordinated by Debra Williston of the Water and Land Resources Division, Science and Technical Support Section. CITATION King County. 2018. King County Lower Duwamish Waterway Source Control Annual Report-Year 2017. Prepared by Department of Natural Resources and Parks, Department of Transportation, and -

Check out the Tech See Page 4

RIDESOUND TRANSIT NEWS FOR SOUND TRANSIT RIDERS VOLUME 7, NO. 2 • SUMMER 2011 RIDE is a Sound Transit publication, distributed on buses, trains and customer service offices. Sound Transit plans, builds, and operates regional transit systems and services to improve mobility for the Central Puget Sound. Sound Transit: 1-800-201-4900 • TTY Relay: 711 Rider Information: 1-888-889-6368 • TTY Relay 711 www.soundtransit.org • [email protected] Union Station • 401 S. Jackson St., Seattle, WA 98104 CS07791 •JUNE •15K 2011 To receive email updates for Sound Transit’s bus or rail Check out the tech See page 4 service, projects or other information, subscribe online 1 at www.soundtransit.org/subscribe. At the intersection of transit and technology you’ll find transit blogs. DIG IT Togo, Balto and Brenda are about to get rolling. The three tunnel boring machines will begin digging These online communities offer easy access to details the University Link light rail tunnels early this summer. about public transit you might not find elsewhere. The two tunnel boring machines that will dig from UW to Capitol Hill are, fittingly, named Togo and A top local site is Seattle Transit Blog Balto after two famous four-legged Huskies. Togo and Balto were the canine heroes of a grueling sled (http://seattletransitblog.com/). We sat down with editor dog relay that delivered medicine 674 miles from Anchorage to Nome, Alaska, during a diphtheria Martin Duke and long-time contributing writer Ben outbreak in 1925. The journey is commemorated each year by the Iditarod sled dog race. -

CANDIDATES: Welcome

King County Democrats Candidate Questionnaire 2021 SurveyMonkey #272 COMPLETE Collector: Web Link 1 (Web Link) Started: Friday, May 21, 2021 5:20:43 PM Last Modified: Saturday, May 22, 2021 6:52:08 AM Time Spent: 13:31:24 IP Address: 156.146.49.140 Page 1: ALL CANDIDATES: Welcome Q1 Your information Name Xtian Gunther Email Address [email protected] Phone Number 2062294085 Q2 Yes I have read instructions at the top of this page Page 2: ALL CANDIDATES: Campaign Contact Information Q3 Campaign contact information Candidate first name Xtian Candidate last name Gunther Campaign email xtiangunther.com Campaign phone (optional) 2062294085 Campaign website (optional) xtiangunther.com Q4 Candidate name pronunciation (optional) Just call me X ;-) Q5 Candidate pronouns (optional) He/him 1 / 24 King County Democrats Candidate Questionnaire 2021 SurveyMonkey Q6 Respondent skipped this question Campaign Manager information (optional) Q7 Respondent skipped this question Campaign Treasurer information (optional) Q8 Respondent skipped this question Campaign Consultant information (optional) Q9 Respondent skipped this question Other Campaign Contact information (optional) Q10 Respondent skipped this question Other paid staff or full-time volunteers (optional) Q11 Additional Campaign contact information (all optional) Facebook Page (campaign) https://www.facebook.com/XtianGuntherSeattleCouncil Instagram TBD LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/in/x-tian-gunther-755b865/ Twitter @XtianGuntherSeattleCouncil YouTube TBD Other URL 1 https://www.xtiangunther.com -

Seattle Streetcar First Hill Line

SEATTLE STREETCAR FIRST HILL LINE Operations & Maintenance Plan v 03 February 2012 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................................2 1. PURPOSE AND SCOPE.......................................................................................................3 2. SYSTEM DESCRIPTION......................................................................................................4 3. SERVICE PLAN..................................................................................................................9 4. OPERATIONS.................................................................................................................13 5. MAINTENANCE..............................................................................................................15 6. STAFFING & BUDGET....................................................................................................23 7. SAFETY .........................................................................................................................25 8. COMMUNICATIONS & MARKETING………………………………………………………………………….….26 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The First Hill Streetcar links First Hill employment centers to the regional transit system via connections on Capitol Hill and in the International District. The First Hill Streetcar also connects diverse and vibrant neighborhoods on Capitol Hill, First Hill, the Central Area, the Chinatown/International District, and Pioneer Square while serving medical