Rediscovering Architecture: Paestum in Eighteenth-Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Organ Works by Puerto Rican Composers

CONTEMPORARY ORGAN WORKS BY PUERTO RICAN COMPOSERS BY Copyright @ 2016 ANDRÉS MOJICA-MARTÍNEZ Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music!and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. __________________________ Dr. James Higdon, chairperson __________________________ Dr. Michael Bauer ________________________ Dr. Paul Laird _________________________ Dr. Bradley Osborn ___________________________ Dr. Luciano Tosta Date defended: April 21, 2016 ii The Dissertation Committee for ANDRÉS MOJICA MARTÍNEZ Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: CONTEMPORARY ORGAN WORKS BY PUERTO RICAN COMPOSERS ___________________________________ Chairperson: Dr. James Higdon Date defended: April 21, 2016 iii Abstract The history of organ music and pipe organs in Puerto Rico dates to Spanish colonial times. Unfortunately, most organ works composed during that period of time did not survive due to fires, hurricanes, the attacks of English and Dutch pirates, and the change of sovereignty in 1898. After the entrance of the United States in 1898, a few organ works were composed and various pipe organs were installed on the island, but no significant developments took place in Puerto Rican organ culture. Recently, with the installation of a three manual Casavant organ at the University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras in 2006, and the creation of the position the author occupies as organist and organ professor at the institution, new opportunities for organ music on the island have flourished. This lecture-recital centers on an investigation of the organ works of four Puerto Rican composers of the twentieth and twenty-first century: William Ortiz, Carlos Lamboy, Raymond Torres-Santos and Roberto Milano. -

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

Redalyc.Arte Y Educación En Valores

Argumentos ISSN: 0187-5795 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco México Paoli, Antonio Arte y educación en valores Argumentos, vol. 23, núm. 62, enero-abril, 2010, pp. 13-37 Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=59515960002 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto PRESEntaCIÓN artE Y EDUCACIÓN EN VALORES Antonio Paoli Este artículo presenta un programa de educación en valores que se pone en práctica mediante el desarrollo de diversas habilidades artísticas. Se muestran ejemplos y explicaciones de su funcionamiento, para que el lector visualice cómo opera este modelo o programa llamado Jugar y Vivir los Valores (JVLV), creado como un sistema de comunicación educativa por el área de investigación “Educación y Comunicación Alternativa” del Departamento de Educación y Comunicación de la UAM-Xochimilco, dentro del marco del Programa Interdisciplinario de Investigación “Desarrollo Humano en Chiapas” de la UAM. La finalidad de JVLV es brindar elementos para propiciar actitudes positivas que ayuden a crear ciudadanos más sanos y felices, con mayor capacidad para la creatividad y con una actitud cooperativa para asimilar mejor los contenidos académicos de la educación primaria. Las actividades del programa están vinculadas a los libros de texto gratuito de la Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP), como apoyo para el maestro y para optimizar los procesos de enseñanza aprendizaje. -

INTERNATIONAL SPORT FORUM WANDA METROPOLITANO MADRID 15Th - 16 Th NOVEMBER 2019 WELCOME to INTERNATIONAL SPORT FORUM MADRID 2019 Dear Colleagues

INTERNATIONAL SPORT FORUM WANDA METROPOLITANO MADRID 15th - 16 th NOVEMBER 2019 WELCOME TO INTERNATIONAL SPORT FORUM MADRID 2019 Dear colleagues, On behalf of the European Sport Nutrition Society and the Strength & Conditioning Society, we would like to extend a warm welcome to join us at the International Sport Forum on Strength & Conditioning & Nutrition in Madrid from 15-16 November 2019.The conference will take place right in the heart of Spain,surrounded by all the history and magic that this unforgettable city has to offer. We are confident that you will find the dynamic and up to date scientific programme, delivered by some of the leading exponents and thinkers in sport nutrition, training, rehabilitation and performance, enjoyable and stimulating. Our congress goal is to bring together experts in each field of research and study, and we aim to provide every opportunity for delegates to learn from, and contribute to, the latest developments in Sports Nutrition and Strength and Conditioning science in a stimulating social and professional setting. We look forward to seeing you there! Prof. Antonio Paoli MD, BSc, FECSS, FACSM • ESNS President • Full Professor of Exercise and Sport Sciences Head, Nutrition and Exercise Physiology Laboratory Department of Biomedical Sciences - School of Medicine Rector’s Delegate for Sport and Wellness University of Padova - Padova (Italy) • President of the Italian Society of Exercise and Sport Sciences (SISMeS) Excmo. Sr. D. José Luis Mendoza Pérez • Chairman of the Universidad Católica de Murcia • Member of the Spanish Olympic Committee Prof. Pedro Emilio Alcaraz, PhD • SCS President • Full Professor in Strength Training. Faculty of Sport Sciences • Head of UCAM Research Center for High Performance Sport • Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia INTERNATIONAL SPORT FORUM COMMITTEE PRESIDENCY COMMITTEE ORGANISING COMMITTEE Anthony J. -

Docuhent Resume Ed 128 505 Ud 016 272 Author

DOCUHENT RESUME ED 128 505 UD 016 272 AUTHOR Estrada, Josephine TITLE Puerto Rican Resource Units. INSTITUTION New York State Education Dept., Albany. Bureau of Migrant Education. PUB DATE 76 NOTE 89p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$4.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Bilingual Education; Cultural Education; Cultural Enrichment; *Curriculum Development; Educational Resources; *Elementary Secondary Education; *Instructional Ails; Intercultural Programs; *Puerto Rican Culture; Puerto Ricans; *Resource Guides; Resource Materials; *Resource Units; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Puerto Rico ABSTRACT Funded by combined Title I Migrant and Title IV Civil Rights Act funds, this guide on six major themes dealing with Puerto Rico was developed primarily for use by teachers in elementary and secondary schools. The guide is designed to provide teachers and students with a better understanding of Puerto Rican and culture. Although the publication was originally developed for use in migrant education programs, its units can serve as a resource foruse in bilingual, social studies, or cross-cultural programs at the elementary and secondary levels. The "Overview" section summarizes and highlights key items relating to the major themes. "Objectives and Activities" provide a framework within which the unitscan be used. The "Teachers' Aids" identify supplemental resources whichare further developed in the bibliography. The bibliography also includes annotations of other books and articles pertaining to Puerto Rican history and culture. Grade levels, publishers, and publication dates (where available) are noted for each entry. In addition,a list of publishers' addresses is provided. (Author/JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. -

Comunicación Social

unam – ents Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Escuela Nacional de Trabajo Social Comunicación Social Lic. María Guadalupe Cortés Osorno Área: Metodología y práctica de trabajo social Semestre: 8 Créditos: 5 Carácter: Obligatoria Sistema Universidad Abierta a Distancia Contenido Pág. Presentación 3 Introducción 4 Objetivo general 6 Perfil de egreso 6 Temario general 7 Unidad 1 El proceso de la comunicación 8 Unidad 2 Comunicación como proceso mediacional 43 Unidad 3 Comunicación en pequeños grupos 85 Unidad 4 Los medios de comunicación y su lenguaje 110 Unidad 5 Estrategias de comunicación y difusión para la 158 intervención del trabajador social en la resolución de una problemática concreta Glosario 183 Preguntas frecuentes 184 Bibliografía 186 2 Presentación La Escuela Nacional de Trabajo Social inicia sus estudios de Licenciatura en Sistema Universidad Abierta, en el año escolar 2003, con el plan de estudios aprobado por el H. Consejo Universitario el 10 de julio de 1996. Reestructurado en 2002 con aprobación del Consejo Académico del Área de las Ciencias Sociales, en su sesión del 26 de noviembre de 2002. En el Sistema Universidad Abierta, la relación entre asesores, estudiantes y material didáctico es fundamental. En este sentido, en la Escuela se puso especial atención para lograr mayor calidad en los materiales. De ésta manera, el material que ahora te presentamos se debe constituir en una herramienta fundamental para tú aprendizaje independiente, cada uno de los componentes que lo integran guardan una congruencia con el fin de que el estudiante pueda alcanzar los objetivos académicos de la asignatura. El material pretende desarrollar al máximo los contenidos académicos, temas y subtemas que son considerados en el programa de estudio de la asignatura. -

83-112 Eseje Prof. Jose Velasco

TE X AWIL ABA , “QUE TENGAS LA CAPACIDAD DE MIRARTE A TI MISMO ”. PRINCIPIOS DE LA FILOSOFÍA EDUCACIONAL TZELTAL , CHIAPAS (M ÉXICO ) Te x awil aba, “I Wish You Had the Ability to Look at Yourself”. Principles of Tzeltal Educational Philosophy, Chiapas (México) * José VELASCO TORO Fecha de recepción: mayo del 2012 Fecha de aceptación y versión final: septiembre del 2012 RESUMEN : La filosofía educativa de la cultura tzeltal, pueblo indio originario de Chiapas, México, constituye un cimiento fundamental en los procesos de la identi- dad y la autonomía comunitaria. Los principios de su hacer pedagógico poseen parale- lismo con los principios de la biología del conocimiento, sincronía sorprendente que permite conocer cómo ocurren los procesos de autoorganización vinculados con el desarrollo humano y comunitario. PALABRAS CLAVE : autonomía, aprendizaje, libertad, hacer y ser social. ABSTRACT : The educational philosophy of culture Tzeltal, Indian people na- tive from Chiapas, Mexico, is a basic principal in the processes of identity and com- munity autonomy. The values of their teachings have parallels with the principles of the Biology of Knowledge, amazing synchronicity that allows knowing how self-or- ganizing processes occur, related to human and community development. KEYWORDS : autonomy, learning, liberty, to do, and social being. I. INTRODUCCIÓN La nación tzeltal se denomina así misma Winik atel, “hombres trabajadores” y hablan el Batsil k’op , “lengua verdadera”. Ellos habitan el K’inal , espacio reconfi- gurado por la actuación humana y su dimensión celeste que constituye la territoriali- dad múltiple del pueblo tzeltal. El K’inal comprende poco más de 2 000 comunida- des que se extienden hacia el noreste y sureste de la ciudad de San Cristóbal de Las Casas en el estado de Chiapas, México. -

Proyecto Del Senado 0336

ESTADO LIBRE ASOCIADO DE PUERTO RICO 19 na. Asamblea 1 ra. Sesión Legislativa Ordinaria SENADO DE PUERTO RICO P. del S. 336 27 de abril de 2021 Presentado por el señor Dalmau Santiago, la señora Gonzalez Huertas y el señor Ruiz Nieves Referido a LEY Para declarar el día 14 de abril de cada año como “El Día del Natalicio de Antonio Paoli”; y para otros fines relacionados. EXPOSICIÓN DE MOTIVOS Don Antonio Paoli fue la primera figura puertorriqueña en adquirir notoriedad internacional en el campo del arte musical. Voz boricua que fue llamado "El Rey de los Tenores" y "El Tenor de los Reyes", fue igualmente el primer talento nacional que conquistó con su arte las cortes europeas. Hijo de doña Amalia Marcano Intriago, oriunda de la Isla Margarita, y del caballero corso don Domingo Paoli Marcatentti, Antonio Paoli nació en Ponce el 14 de abril de 1871. Estudió en la Escuela de Párvulos guiado por el profesor Ramón Marín. Y posteriormente descubrió su afinidad con el canto durante el concierto que el tenor italiano Pietro Baccei presentó en el Teatro La Perla de Ponce. Fueron los padres de Antonio quienes fomentaron en él el amor por el arte. Mas el futuro tenor apenas cumplía los 12 años cuando sus progenitores fallecieron. Ante el hecho, Amalia, hermana mayor de Antonio, decidió trasladarse a España con sus 2 hermanos. Con ese debut tan exitoso comienza Paoli su carrera de triunfos por los mejores escenarios de Europa, Asia, África y América. Con su innegable talento interpretativo, la fama de Antonio Paoli se extendió rápidamente por el continente europeo. -

THE RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE Given Below Is the Featured Artist(S) of Each Issue (D=Discography, B=Biographical Information)

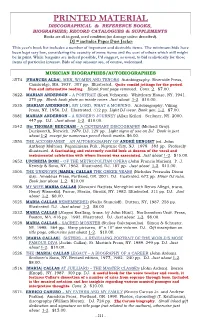

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, BIOGRAPHIES; RECORD CATALOGUES & SUPPLEMENTS Books are all in good, used condition (no damage unless described). DJ = includes Paper Dust Jacket This year’s book list includes a number of important and desirable items. The minimum bids have been kept very low, considering the scarcity of some items and the cost of others which still might be in print. While bargains are indeed possible, I’d suggest, as usual, to bid realistically for those items of particular interest. Bids of any amount are, of course, welcomed. MUSICIAN BIOGRAPHIES/AUTOBIOGRAPHIES 3574. [FRANCES ALDA]. MEN, WOMEN AND TENORS. Autobiography. Riverside Press, Cambridge, MA. 1937. 307 pp. Illustrated. Quite candid jottings for the period. Fun and informative reading. Blank front page removed. Cons. 2. $7.00. 3622. MARIAN ANDERSON – A PORTRAIT (Kosti Vehanen). Whittlesey House, NY. 1941. 270 pp. Blank book plate on inside cover. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3535. [MARIAN ANDERSON]. MY LORD, WHAT A MORNING. Autobiography. Viking Press, NY. 1956. DJ. Illustrated. 312 pp. Light DJ wear. Book gen. 1-2. $7.00. 3581. MARIAN ANDERSON – A SINGER’S JOURNEY (Allan Keiler). Scribner, NY. 2000. 447 pp. DJ. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3542. [Sir THOMAS] BEECHAM – A CENTENARY DISCOGRAPHY (Michael Gray). Duckworth, Norwich. 1979. DJ. 129 pp. Light signs of use on DJ. Book is just about 1-2 except for numerous pencil check marks. $6.00. 3550. THE ACCOMPANIST – AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ANDRÉ BENOIST (ed. John Anthony Maltese). Paganiniana Pub., Neptune City, NJ. 1978. 383 pp. Profusely illustrated. A fascinating and extremely candid look at dozens of the vocal and instrumental celebrities with whom Benoist was associated. -

VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs Minimum Bid As Indicated Per Item

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs Minimum bid as indicated per item. Listings “Just about 1-2” should be considered as mint and “Cons. 2” with just slight marks. For collectors searching top copies, you’ve come to the right place! The farther we get from the era of production (in many cases now 100 years or more), the more difficult it is to find such excellent extant pressings. Some are actually from mint dealer stocks and others the result of having improved copies in my own collection via dozens of collections purchased over the past fifty years. * * * For those looking for the best sound via modern reproduction, those items marked “late” are usually of high quality shellac, pressed in the 1950-55 period. A number of items in this particular catalogue are excellent pressings from that era. Also featured are many “Z” shellac Victors, their best quality surface material (produced in the later 1930s) and PW (Pre-War) Victor, almost as good surface material as “Z”. Likewise laminated PW Columbia pressings (1923-1940) offer similarly fine sound. * * * Please keep in mind that the minimum bids are in U.S. Dollars, a benefit to most collectors. These figures do not indicate the “value” of the records but rather the lowest minimum bid I can accept. Some will sell for much more, although bids at any figure from the minimum on up are welcomed and appreciated. To avoid possible tie winning bids (which would otherwise be assigned to the earlier received bid), I’d suggest adding a cents amount to your bid. * * * “Text label on verso.” For a brief period (1912-1914), Victor pressed silver-on-black labels on the reverse sides of some of their single-faced recordings, usually featuring translations of the text or related comments. -

Re-Discovering the Trumpet Music of Roberto Milano: a Study of His Dúo Para Trompeta Y Piano, Sinfonietta No

Re-Discovering the Trumpet Music of Roberto Milano: A Study of his Dúo para trompeta y piano, Sinfonietta No. 2 for Flugelhorn and String Orchestra (A Desert Pilgrim), and Idylls of the King for Three Trumpets. BY Copyright © 2015 Nitai Pons-Pérez Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Chairperson, Paul Laird Steve Leisring Michael Davidson Daniel Gailey William Dentler Date defended: May 5, 2015 The Document Committee for Nitai Pons-Pérez certifies that this is the approved version of the following document: Re-Discovering the Trumpet Music of Roberto Milano: A Study of his Dúo para trompeta y piano, Sinfonietta No. 2 for Flugelhorn and String Orchestra (A Desert Pilgrim), and Idylls of the King for Three Trumpets. Chairperson, Paul Laird Date approved: May 5, 2015 Abstract Roberto L. Milano’s musical output exhibits a diversity of styles and compositional genres. Most of his works are influenced by his passion for early western sacred and secular music. Milano was consistent with the use of modal sonorities and nonfunctional harmonies in combination with structures and melodic elements from the Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods. His music is appealing to audiences and demonstrates how he combines different influences into a cohesive whole. His unpublished works for trumpet are only known by a small group of Puerto Rican musicians. This document illustrates some of the characteristics of Milano’s Dúo para trompeta y piano, Sinfonietta No. 2 for Flugelhorn and String Orchestra, and Idylls of the King for Three Trumpets. -

Carrero, Milagros TITLE Puerto Rico and the Puerto Ricans; a Teaching and Resource Unit for Upper Level Spanish Students Or Social Studies Classes

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 085 988 FL 004 098 AUTHOR Carrero, Milagros TITLE Puerto Rico and the Puerto Ricans; A Teaching and Resource Unit for Upper Level Spanish Students or Social Studies Classes. INSTITUTION Prince George's County Board of Education, Upper Marlboro, Md. PUB DATE 73 NOTE 89p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Bibliographies; English; Ethnic Groups; Information Sources; Latin American Culture; Minority Groups; Puerto Rican Culture; *Puerto Ricans; Resource Guides; *Resource Materials; *Resource Units; *Social Studies; *Spanish; Spanish Culture; Spanish Speaking; Unit Plan ABSTRACT The subject of this teaching and resource unit for Spanish students or social studies classes is Puerto Rico and the Puerto Ricans. The unit has sections dealing with the present conditions of the Puerto Ricans, their culture, and historical perspectives. The appendixes contain: (.1) Demands of the Puerto Ricans,(2) Notable Puerto Ricans,(3) Background Information for the Teacher, (4) Legends, (5) Spanglish, (6) Puerto Rican Dishes, and (7) Sources for Information and Materials. Also provided is a bibliography of additional sources of information on Puerto Rico and the Puerto Ricans. The text is in English. (SK) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLECOPY US DEPANTNIE NT OF HEALTH. 03 EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF Co EDUCATION THIS DOCuTAENT HAS SEEN a C PRO Cr oucE0 (*Act, As aEcEHrED caoTA THE PERSON Oa OaGANicAtIoNOTHOIAT tr1 ,ip4citPOINTS OF VIEW ON OPINIONS STATED 00 NOT NECESSARILY REPAE 00 SENT oTricAL. NATIONAL. INSTITUTE Of C) EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY PUERTO RICO AND THE PUERTO RICANS A Teaching and Resource Unit for Upper Level Spanish Students or Social Studies Classes By: Milagros Carrero.