Storytelling Adventure System Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Character Creation Guidelines.Pages

The Giovanni Chronicles Vampire 20th Anniversary Player Characters Create a vampire from any of the clans listed below. This chronicle starts off in medieval times so I’d like to keep it as pure as possible, therefore please consider not using Bloodlines. If you are adamant that you want to play a bloodline character please make sure it fits into the time frame and explain why you have to play it. I’m interested in telling a fun and a good story that starts at the inception of some major changes in vampire lore. I don’t want to have any comebacks because your bloodline gives you major advantages in the meta. Assamite , Brujah, Followers of Set, Gangrel, Lasombra, Malkavian, Nosferatu, Ravnos, Toreador, Tremere, Tzimisce, Ventrue If you want to research real life history to get a better feel for how your character lives then the year is 1444 and the place is Romania. Basically the Turks are taking over everything as the Ottoman Empire expands. Your average serf would know little outside of their village and some wouldn’t know much outside of their father’s pig farm. You are probably Christian, or Pagan, the Muslims are terrorising lands headed West. It’s basically their time to shine as Western terrorism has been failing recently. Sounds familiar somehow. I would recommend you do not research Kindred history, your characters will start off as humans and so aside from things that go bump in the night, vampire activities are very much concealed under the masquerade. You will be writing or at the very least witnessing Kindred history as part of this Chronicle so much of what you read could very well be science fiction by the time you encounter it. -

SILVER AGE SENTINELS (D20)

Talking Up Our Products With the weekly influx of new roleplaying titles, it’s almost impossible to keep track of every product in every RPG line in the adventure games industry. To help you organize our titles and to aid customers in finding information about their favorite products, we’ve designed a set of point-of-purchase dividers. These hard-plastic cards are much like the category dividers often used in music stores, but they’re specially designed as a marketing tool for hobby stores. Each card features the name of one of our RPG lines printed prominently at the top, and goes on to give basic information on the mechanics and setting of the game, special features that distinguish it from other RPGs, and the most popular and useful supplements available. The dividers promote the sale of backlist items as well as new products, since they help customers identify the titles they need most and remind buyers to keep them in stock. Our dividers can be placed in many ways. These are just a few of the ideas we’ve come up with: •A divider can be placed inside the front cover or behind the newest release in a line if the book is displayed full-face on a tilted backboard or book prop. Since the cards 1 are 11 /2 inches tall, the line’s title will be visible within or in back of the book. When a customer picks the RPG up to page through it, the informational text is uncovered. The card also works as a restocking reminder when the book sells. -

An Adventure for Exalted Using the Storytelling Adventure System

It is better for a city to be governed by a good man than by good laws. – Aristotle An adventure for Exalted using the Storytelling Adventure System Written by Adam Eichelberger Developed by Eddy Webb Edited by Genevieve Podleski Layout by Jessica Mullins Art: Justin Norman, Andy Brase, Ross Campbell, Andie Tong, Shane Coppage, Pop Mhan, Eva Widermann, Brandon Graham, Melissa Uran, UDON, and Imaginary Friends Studio STORYTELLING ADVENTURE SYSTEM White Wolf Publishing, Inc. MENTAL OOOOO 2075 West Park Place Blvd PHYSICAL OOOOO Suite G Stone Mountain, GA 30087 SOCIAL OOOOO It is better for a city to be governed by a good man than by good laws. – Aristotle An adventure for Exalted using the Storytelling Adventure System Written by Adam Eichelberger Developed by Eddy Webb Edited by Genevieve Podleski Layout by Jessica Mullins STORYTELLING ADVENTURE SYSTEM Art: Justin Norman, Andy Brase, Ross Campbell, Andie Tong, Shane Coppage, Pop Mhan, Eva Widermann, Brandon Gra- SCENES MENTAL OOOOO XP LEVEL ham, Melissa Uran, UDON, and Imaginary Friends Studio PHYSICAL OOOOO 14 SOCIAL OOOOO o-34 White Wolf Publishing, Inc. © 2008 CCP hf. All rights reserved. Reproduction without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden, except for the purposes of reviews, and one printed copy which may be reproduced for personal use only. White Wolf, Vampire and World of Darkness are registered trademarks of CCP hf. All rights reserved. Vampire the Requiem, Werewolf the Forsaken, Mage the Awakening, Promethean the Created, Storytelling System and Parlor Games are trademarks of CCP hf. All rights reserved. 2075 West Park Place Blvd All characters, names, places and text herein are copyrighted by CCP hf. -

MARCH 1St 2018

March 1st We love you, Archivist! MARCH 1st 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

An Adventure for Exalted Using the Storytelling Adventure System

If anyone preach to you— besides that which you have received, let him be Anathema. – Galatians 1:9 (Douay-Rheims translation) An adventure for Exalted using the Storytelling Adventure System STORYTELLING ADVENTURE SYSTEM SCENES MENTAL OOOOO XP LEVEL PHYSICAL OOOOO Written by Adam Eichelberger 12 SOCIAL OOOOO 35 Developed by Eddy Webb and Michael Goodwin Edited by Genevieve Podleski Layout by Tiara Lynn Agresta Art by XX White Wolf Publishing, Inc. © 2011 CCP hf. All rights reserved. Reproduction without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden, except for the purposes of reviews, and one printed copy which may be reproduced for personal use only. White Wolf, Vampire and World of Darkness are registered trademarks of CCP hf. All rights reserved. Vampire the Requiem, Werewolf the Forsaken, Mage the Awakening, Promethean the Created, Changeling the 2075 West Park Place Blvd Lost, Hunter the Vigil, Storytelling System and Parlor Games are trademarks of CCP hf. All rights reserved. All characters, names, places and text herein are copyrighted by CCP hf. CCP North America Inc. is a wholly owned Suite G subsidiary of CCP hf. The mention of or reference to any company or product in these pages is not a challenge to the trademark or copyright concerned. This book uses the supernatural for settings, characters and themes. Stone Mountain, GA 30087 All mystical and supernatural elements are fiction and intended for entertainment purposes only. This book contains mature content. Reader discretion is advised. Check out White Wolf online at http://www.white-wolf.com If anyone preach to you— besides that which you have received, let him be Anathema. -

A Player's Guide to Tabletop Role-Playing Games in Libraries

Western University Scholarship@Western FIMS Publications Information & Media Studies (FIMS) Faculty 2019 Roll for Initiative: A Player’s Guide to Tabletop Role-Playing Games in Libraries Carlie Forsythe University of Western Ontario, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/fimspub Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Citation of this paper: Forsythe, Carlie, "Roll for Initiative: A Player’s Guide to Tabletop Role-Playing Games in Libraries" (2019). FIMS Publications. 343. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/fimspub/343 Running head: ROLL FOR INITIATIVE: A PLAYER’S GUIDE TO TTRPGS IN LIBRARIES 1 Roll for Initiative: A Player’s Guide to Tabletop Role-Playing Games in Libraries Submitted by Carlie Forsythe Supervised by Dr. Heather Hill LIS 9410: Independent Study Submitted: August 9, 2019 Updated: February 4, 2020 ROLL FOR INITIATIVE: A PLAYER’S GUIDE TO TTRPGS IN LIBRARIES 2 INTRODUCTION GM: You see a creepy subterranean creature hanging onto the side of a pillar. It is peering at you with one large, green eye. What do you do? Ranger: I’m going to drink this invisibility potion and cross this bridge to get a closer look. I’m also going to nock an arrow and hold my attack in case it notices me. Cleric: One large green eye. Where have I seen this before? Wait, I think that’s a Nothic. Bard Can I try talking to it? GM: Sure, make a persuasion check. Bard: I rolled a 7, plus my modifier is a 3, so a 10. What does that do? GM: The Nothic notices you and you can feel its gaze penetrating your soul. -

WOD CHI ADV.Indd

To Frankie that quarter-moon sky looked darker and all the iron apparatus of the El taller than ever. The artificial tenement light sweeping across the tracks made even the snow seem artificial, like snow off a dime-store counter. Only the rails seemed real, and to move a bit with terrible intent. — Nelson Algren, The Man With The Golden Arm An adventure for the World of Darkness using the Storytelling Adventure System Written by: Will Hindmarch Additional Writing: Ken Hite, Bill Bridges Layout: matt milberger Art: sam araya World of Darkness created by Mark Rein•Hagen STORYTELLING ADVENTURE SYSTEM SCENES MENTAL OOOOO XP LEVEL PHYSICAL OOOOO White Wolf Publishing, Inc. 8 SOCIAL OOOOO 0-34 1554 Litton Drive Stone Mountain, GA 30083 To Frankie that quarter-moon sky looked darker and all the iron apparatus of the El taller than ever. The artificial tenement light sweeping across the tracks made even the snow seem artificial, like snow off a dime-store counter. Only the rails seemed real, and to move a bit with terrible intent. — Nelson Algren, The Man With The Golden Arm An adventure for the World of Darkness using the Storytelling Adventure System Written by: Will Hindmarch Additional Writing: Ken Hite, Bill Bridges Layout: matt milberger Art: sam araya World of Darkness created by Mark Rein•Hagen STORYTELLING ADVENTURE SYSTEM SCENES MENTAL OOOOO XP LEVEL PHYSICAL OOOOO 8 SOCIAL OOOOO 0-34 White Wolf Publishing, Inc. 1554 Litton Drive © 2006 White Wolf, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden, except for the purposes of reviews, and for blank character sheets, which may be reproduced for personal use only. -

Lightweight Omnipotent Roleplaying Engine by Gregory Weir

LORE Lightweight Omnipotent Roleplaying Engine By Gregory Weir Table of Contents Introduction..............................................................................................................................................................3 Basics.......................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters............................................................................................................................................................4 Rolling Dice .......................................................................................................................................................4 Taking 6..........................................................................................................................................................5 Contested Rolls...............................................................................................................................................5 Time....................................................................................................................................................................5 Modules...............................................................................................................................................................5 Characters ...............................................................................................................................................................6 -

Adventures in the Classroom Creating Role-Playing Games Based on Traditional Stories for the High School Curriculum" (2012)

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2012 Adventures in the Classroom Creating Role- Playing Games Based on Traditional Stories for the High School Curriculum Csenge Virág Zalka East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Educational Methods Commons, and the Game Design Commons Recommended Citation Zalka, Csenge Virág, "Adventures in the Classroom Creating Role-Playing Games Based on Traditional Stories for the High School Curriculum" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1469. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1469 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adventures in the Classroom Creating Role-Playing Games Based on Traditional Stories for the High School Curriculum ______________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Curriculum and Instruction East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Reading with a concentration in Storytelling ___________________ by Csenge V. Zalka August 2012 _________________ Dr. Joseph Sobol, Chair Delanna Reed Todd Emma Harold L. Daniels Keywords: Role-Playing, Games, Storytelling, High School, Education, Mythology, Folktales, Game Design ABSTRACT Adventures in the Classroom Creating Role-Playing Games Based on Traditional Stories for the High School Curriculum by Csenge V. Zalka The goal of this thesis is to develop a template for turning traditional stories into role-playing games for the high school curriculum. -

Time of Judgement: Vampire. Gehenna: the Final Night

A Race Against Armageddon For millennia, vampires have fed on the living, hidden in the shadows of mortal society. Legends say the undead descend from Caine, the first murderer portrayed in the Bible, who passed on his curse through his blood. Those same legends speak of a final reckoning, when Caine and his mad children will rise from slumber and consume all the undead. Vampires call this time Gehenna. For the vampire Beckett, a researcher among the undead, it means one last shot at understanding the mysteries of the get of Caine—and at outrunning his own sins. Vampire: Gehenna, the Final Night is the first act of the Time of Judgment, telling the story of a wide-ranging Armageddon among the supernatural entities of the World of Darkness®. Act One of Three dark fantasy ISBN 1-58846-855-0 $7.99 U.S WW11910 A Race Against Armageddon For millennia, vampires have fed on the living, hidden in the shadows of mortal society. Legends say the undead descend from Caine, the first murderer portrayed in the Bible, who passed on his curse through his blood. Those same legends speak of a final reckoning, when Caine and his mad children will rise from slumber and consume all the undead. Vampires call this time Gehenna. For the vampire Beckett, a researcher among the undead, it means one last shot at understanding the mysteries of the get of Caine—and at outrunning his own sins. Vampire: Gehenna, the Final Night is the first act of the Time of Judgment, telling the story of a wide-ranging Armageddon among the supernatural entities of the World of Darkness®. -

SAS Falling Scales.Indd

Civility must be rewarded. If it isn’t rewarded, there’s no use for it. There’s just no use for it at all. — Dr. Logan, Day of the Dead An adventure for the World of Darkness using the Storytelling Adventure System Sample file STORYTELLING ADVENTURE SYSTEM SCENES MENTAL OOOOO XP LEVEL PHYSICAL OOOOO 10 SOCIAL OOOOO 0-34 Civility must be rewarded. If it isn’t rewarded, there’s no use for it. There’s just no use for it at all. — Dr. Logan, Day of the Dead An adventure for the World of Darkness using the Storytelling Adventure System Sample file Written by Matt McFarland Developed by Chuck Wendig Edited by Michelle Lyons Layout by Mike Chaney Art: Brian Leblanc and Eric Kolbek © 2012 CCP hf. All rights reserved. Reproduction without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden, except for the purposes of reviews, and one printed copy which may be reproduced for personal use only. White Wolf, Vampire and World of Darkness are registered trademarks of CCP hf. All rights reserved. Vampire the Requiem, Werewolf the Forsaken, Mage the Awakening, Promethean the Created, Changeling the Lost, Hunter the Vigil, Geist the Sin-Eaters, Storytelling System and Parlor Games are trademarks of CCP hf. All rights reserved. All characters, names, places and text herein are copyrighted by CCP hf. CCP North America Inc. is a wholly owned subsidiary of CCP hf. The mention of or reference to any company or product in these pages is not a challenge to the trademark or copyright concerned. This book uses the supernatural for settings, characters and themes. -

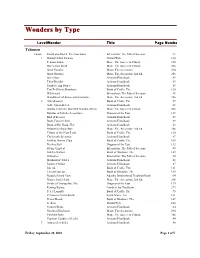

Wonders by Type

Wonders by Type LevelWonder Title Page Number Talisman Unique Khalil aba-Malek, The Iron Satan Infernalism: The Path of Screams 92 1 Digital Online Package Digital Web 100 Fencing Square Mage: The Sorcerers Crusade 285 Hare's-foot Ward Mage: The Sorcerers Crusade 286 Spirit Goggles Mage: The Ascension 294 Spirit Goggles Mage: The Ascension, 2nd Ed. 286 Spy-Glass Artisans Handbook 89 Time-Divider Artisans Handbook 89 Truth-Seeing Stones Artisans Handbook 89 Tsu-Ti (Divine Bamboo) Book of Crafts, The 120 Witchward Infernalism: The Path of Screams 89 Woodblock of Auspicious Formulae Mage: The Ascension, 2nd Ed. 286 2 Abh-t Dagger Book of Crafts, The 59 Adze Unparalleled Artisans Handbook 88 Anulus Vigil (the Watchful Guardian Ring) Mage: The Sorcerers Crusade 286 Bangles of Infinite Acceptance Dragons of the East 129 Bird of Reason Artisans Handbook 87 Body-Forger's Arm Artisans Handbook 89 Bond of Ibn Daud, The Artisans Handbook 83 Brittany's Music Box Mage: The Ascension, 2nd Ed. 286 Classic of the Plain Lady Book of Crafts, The 120 Clockwork Sycamore Artisans Handbook 87 Endless Ammo Clips Book of Crafts, The 103 Fix-Sea Staff Dragons of the East 132 Flying Unguent Infernalism: The Path of Screams 89 Golden Walnut Book of Shadows, The 149 Grimoires Infernalism: The Path of Screams 90 Hephaistos' Tables Artisans Handbook 88 Jonah's Chariot Artisans Handbook 87 Juk Ak Book of Crafts, The 121 Lycanthroscope Book of Shadows, The 149 Magick Sword Coin Akashic Brotherhood Tradition Book 64 Master Joro's Sash Mage: The Ascension, 2nd Ed. 286