Tabletop Role-Playing Games and the Experience of Imagined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giocare Con Le Emozioni Giocare Con Le Emozioni

A cura di Claudia Cangini & Michele Gelli Giocare con le Emozioni Giocare con le Emozioni A Cura di: Claudia Cangini, Michele Gelli Traduzioni: Marco Costantini (Innamorarzi ancora, Le fredde ossa) Revisione Testi: Claudia Cangini, Lavinia Fantini, Michele Gelli, Mauro Ghibaudo, Moreno Roncucci, Luca Veluttini Grafica e Impaginazione: Claudia Cangini Immagine di Copertina: Leon Bakst (Two Boetian Girls, costumi per il balletto Narcisse) Finito di Stampare: Aprile 2011 presso DigitalPrint, Rimini Copyright: Rispettivi Autori, InterNosCon 2011. Tutti i diritti riservati. Distribuzione: Narrattiva Una Pubblicazione: www.internoscon.it 2 Giocare con le Emozioni Contenuti Introduzione 5 Once more with feeling di Claudia Cangini Giocare con le emozioni 7 I freddi dadi di Jesse Burneko 13 Metti un’emozione nella tua simulazione - Dare profondità agli eventi di role-play simulation per le situazioni di rischio ambientale e sanitario utilizzando tecniche di coinvolgimento emotivo sviluppate nell’ambito dei role-playing games di Andrea Castellani 29 Il piacere delle lacrime di Ezio Melega A Cura di: Claudia Cangini, Michele Gelli 37 Innamorarsi ancora Traduzioni: Marco Costantini (Innamorarzi ancora, Le fredde ossa) di Emily Care Boss 41 I nemici del gioco appassionato: pigrizia, tradizionalismo, pregiudizio, Revisione Testi: Claudia Cangini, Lavinia Fantini, Michele Gelli, vergogna, e ancora pigrizia Mauro Ghibaudo, Moreno Roncucci, Luca Veluttini di Mattia Bulgarelli Grafica e Impaginazione: Claudia Cangini 53 Role Playing & Role Playing Game: ruoli ed emozioni di Filippo Porcelli Immagine di Copertina: Leon Bakst (Two Boetian Girls, costumi per il balletto 59 110%: tecniche che colpiscono al cuore Narcisse) di Matteo Suppo Finito di Stampare: Aprile 2011 presso DigitalPrint, Rimini 65 Un drago in Vietnam - Un approccio storico al gioco. -

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

SILVER AGE SENTINELS (D20)

Talking Up Our Products With the weekly influx of new roleplaying titles, it’s almost impossible to keep track of every product in every RPG line in the adventure games industry. To help you organize our titles and to aid customers in finding information about their favorite products, we’ve designed a set of point-of-purchase dividers. These hard-plastic cards are much like the category dividers often used in music stores, but they’re specially designed as a marketing tool for hobby stores. Each card features the name of one of our RPG lines printed prominently at the top, and goes on to give basic information on the mechanics and setting of the game, special features that distinguish it from other RPGs, and the most popular and useful supplements available. The dividers promote the sale of backlist items as well as new products, since they help customers identify the titles they need most and remind buyers to keep them in stock. Our dividers can be placed in many ways. These are just a few of the ideas we’ve come up with: •A divider can be placed inside the front cover or behind the newest release in a line if the book is displayed full-face on a tilted backboard or book prop. Since the cards 1 are 11 /2 inches tall, the line’s title will be visible within or in back of the book. When a customer picks the RPG up to page through it, the informational text is uncovered. The card also works as a restocking reminder when the book sells. -

Press Release: a Fascinating and Compelling Look

GV DOCU-SERIES www.graffi ti verite.com PRESS RELEASE Contact: Loida, Account Executive For Immediate Release PO Box 74033 Los Angeles, CA 90004 Tel: 323/856-9256 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.graffitiverite.com PA RT 1 A FASCINATING A ND C OMPELLING L OOK BEHIND T HE VEIL os Angeles, CA--Bryan World Press... GV15 GAMING OUR REALITY: Writing and Game Design from an Alternate Perspective directed by documentary filmmaker Bob Bryan is described as a far ranging one-on-one L“conversation” with Transmedia giant Flint Dille. Flint’s background in TV and Game Design is diverse and extensive. “A Powerful Educational tool. I learned something about myself because of this film. Flint made it clear that we create codes to break down, decipher and analyze ‘reality’ at our own pace and from our own point-of-view…” - Miles B., A Rabid Online Video Gamer Early on in his career he was best known as a writer/producer on the Transformers, G.I.Joe, Garbage Pail Kids, InHumanoids, Mr.T Animated TV Series and eventually as writer/game designer on Vin Diesels Chronicles of Riddick: Assault on Dark Athena, Escape from Butcher Bay, Batman: Rize of Sin Tzu, Mission Impossible, James Bond: Tomorrow Never Dies, Dead to Rights , Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer, Wheelman, Visionaries: Knights of the Magical Light and more recently Diablo lll. Mr. Dille has written four interactive novels, five regular novels, graphic novels and comic books. According to Mr. Dille’s bio on IMDB: “Flint Dille has spent most of his creative life on the porous border between the game business and the film business, and firmly believes that it is all becoming one big media industry. -

Dragon Magazine #151

Issue #151 SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS Vol. XIV, No. 6 Into the Eastern Realms: November 1989 11 Adventure is adventure, no matter which side of the ocean you’re on. Publisher The Ecology of the Kappa David R. Knowles Jim Ward 14 Kappa are strange, but youd be wise not to laugh at them. Editor Soldiers of the Law Dan Salas Roger E. Moore 18 The next ninja you meet might actually work for the police. Fiction editor Earn Those Heirlooms! Jay Ouzts Barbara G. Young 22Only your best behavior will win your family’s prize katana. Assistant editors The Dragons Bestiary Sylvia Li Anne Brown Dale Donovan 28The wang-liang are dying out — and they’d like to take a few humans with them. Art director Paul Hanchette The Ecology of the Yuan-ti David Wellman 32To call them the degenerate Spawn of a mad god may be the only nice Production staff thing to say. Kathleen C. MacDonald Gaye OKeefe Angelika Lukotz OTHER FEATURES Subscriptions The Beastie Knows Best Janet L. Winters — Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser 36 What are the best computer games of 1989? You’ll find them all here. U.S. advertising Role-playing Reviews Sheila Gailloreto Tammy Volp Jim Bambra 38Did you ever think that undead might be . helpful? U.K. correspondent The Role of Books John C. Bunnell and U.K. advertising 46 New twists on an old tale, and other unusual fantasies. Sue Lilley The Role of Computers — Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser 52 Fly a Thunderchief in Vietnam — or a Silpheed in outer space. -

Thursday Friday

3:00 PM – 4:00 PM Thursday 4:00 PM – 5:00 PM 12:00 PM – 1:00 PM “Hannibal and the Second Punic War” “The History of War Gaming” Speaker: Nikolas Lloyd Location: Conestoga Room Speaker: Paul Westermeyer Location: Conestoga Room Description: The Second Punic War perhaps could have been a victory for Carthage, and today, church services and degree Description: Come learn about the history of war gaming from its certificates would be in Punic and not in Latin. Hannibal is earliest days in the ancient world through computer simulations, considered by many historians to be the greatest ever general, and focusing on the ways commercial wargames and military training his methods are still studied in officer-training schools today, and wargames have inspired each other. modern historians and ancient ones alike marvel at how it was possible for a man with so little backing could keep an army made 1:00 PM – 2:00 PM up of mercenaries from many nations in the field for so long in Rome's back yard. Again and again he defeated the Romans, until “Conquerors Not Liberators: The 4th Canadian Armoured Division in the Romans gave up trying to fight him. But who was he really? How Germany, 1945” much do we really know? Was he the cruel invader, the gallant liberator, or the military obsessive? In the end, why did he lose? Speaker: Stephen Connor, PhD. Location: Conestoga Room Description: In early April 1945, the 4th Canadian Armoured Division 5:00 PM – 6:00 PM pushed into Germany. In the aftermath of the bitter fighting around “Ethical War gaming: A Discussion” Kalkar, Hochwald and Veen, the Canadians understood that a skilled enemy defending nearly impassable terrain promised more of the Moderator: Paul Westermeyer same. -

The Style of Video Games Graphics: Analyzing the Functions of Visual Styles in Storytelling and Gameplay in Video Games

The Style of Video Games Graphics: Analyzing the Functions of Visual Styles in Storytelling and Gameplay in Video Games by Yin Wu B.A., (New Media Arts, SIAT) Simon Fraser University, 2008 Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Interactive Arts and Technology Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology Yin Wu 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2012 Approval Name: Yin Wu Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Style of Video Games Graphics: Analyzing the Functions of Visual Styles in Storytelling and Gameplay in Video Games Examining Committee: Chair: Carman Neustaedter Assistant Professor School of Interactive Arts & Technology Simon Fraser University Jim Bizzocchi, Senior Supervisor Associate Professor School of Interactive Arts & Technology Simon Fraser University Steve DiPaola, Supervisor Associate Professor School of Interactive Arts & Technology Simon Fraser University Thecla Schiphorst, External Examiner Associate Professor School of Interactive Arts & Technology Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: October 09, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract Every video game has a distinct visual style however the functions of visual style in game graphics have rarely been investigated in terms of medium-specific design decisions. This thesis suggests that visual style in a video game shapes players’ gaming experience in terms of three salient dimensions: narrative pleasure, ludic challenge, and aesthetic reward. The thesis first develops a context based on the fields of aesthetics, art history, visual psychology, narrative studies and new media studies. Next it builds an analytical framework with two visual styles categories containing six separate modes. This research uses examples drawn from 29 games to illustrate and to instantiate the categories and the modes. -

Fantasy Adventure Game Expert Rulebook

TABLE OF CONTENTS Reference Charts from D&D® Basic X2 Character Attacks X26 PART 1: INTRODUCTION X3 Monster Attacks X26 How to Use This Book X3 PART 6: MONSTERS X27 The Scope of the Rules X3 MONSTER LIST: Animals to Wyvern . X28 Standard Terms Used in This Book X3 PART 7: TREASURE X43 Assisting A Novice Player X3 Treasure Types X43 The Wilderness Campaign X3 Magic Items X44 High and Low Level Characters X4 Explanations X45 Using D&D® Expert Rules With an Early Swords X45 Edition of the D&D® Basic Rules X4 Weapons and Armor X48 PART 2: PLAYER CHARACTER INFORMATION X5 Potions X48 Charts and Tables X5 Scrolls X48 Character Classes X7 Rings X49 CLERICS X7 Wands, Staves and Rods X49 DWARVES X7 Miscellaneous Magic Items X50 ELVES X7 PART 8: DUNGEON MASTER INFORMATION X51 FIGHTERS X7 Handling Player Characters X51 HALFLINGS X7 Magical Research and Production X51 MAGIC-USERS X7 Castles, Strongholds and Hideouts X52 THIEVES X8 Designing a Dungeon (recap) X52 Levels Beyond Those Listed X8 Creating an NPC Party X52 Cost of Weapons and Equipment X9 NPC Magic Items X52 Explanation of Equipment X9 Designing a Wilderness X54 PART 3: SPELLS Xll Wandering Monsters X55 CLERICAL SPELLS Xll Travelling In the Wilderness X56 First Level Clerical Spells Xll Becoming Lost X56 Second Level Clerical Spells X12 Wilderness Encounters X57 Third Level Clerical Spells X12 Wilderness Encounter Tables X57 Fourth Level Clerical Spells X13 Castle Encounters X59 Fifth Level Clerical Spells X13 Dungeon Mastering as a Fine Art X59 MAGIC-USER AND ELF SPELLS X14 Sample Wilderness Key and Maps X60 First Level Magic-User and Elf Spells SampleX14 fileHuman Lands X60 Second Level Magic-User and Elf Spells X14 Non-Humans '. -

An Adventure for Exalted Using the Storytelling Adventure System

It is better for a city to be governed by a good man than by good laws. – Aristotle An adventure for Exalted using the Storytelling Adventure System Written by Adam Eichelberger Developed by Eddy Webb Edited by Genevieve Podleski Layout by Jessica Mullins Art: Justin Norman, Andy Brase, Ross Campbell, Andie Tong, Shane Coppage, Pop Mhan, Eva Widermann, Brandon Graham, Melissa Uran, UDON, and Imaginary Friends Studio STORYTELLING ADVENTURE SYSTEM White Wolf Publishing, Inc. MENTAL OOOOO 2075 West Park Place Blvd PHYSICAL OOOOO Suite G Stone Mountain, GA 30087 SOCIAL OOOOO It is better for a city to be governed by a good man than by good laws. – Aristotle An adventure for Exalted using the Storytelling Adventure System Written by Adam Eichelberger Developed by Eddy Webb Edited by Genevieve Podleski Layout by Jessica Mullins STORYTELLING ADVENTURE SYSTEM Art: Justin Norman, Andy Brase, Ross Campbell, Andie Tong, Shane Coppage, Pop Mhan, Eva Widermann, Brandon Gra- SCENES MENTAL OOOOO XP LEVEL ham, Melissa Uran, UDON, and Imaginary Friends Studio PHYSICAL OOOOO 14 SOCIAL OOOOO o-34 White Wolf Publishing, Inc. © 2008 CCP hf. All rights reserved. Reproduction without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden, except for the purposes of reviews, and one printed copy which may be reproduced for personal use only. White Wolf, Vampire and World of Darkness are registered trademarks of CCP hf. All rights reserved. Vampire the Requiem, Werewolf the Forsaken, Mage the Awakening, Promethean the Created, Storytelling System and Parlor Games are trademarks of CCP hf. All rights reserved. 2075 West Park Place Blvd All characters, names, places and text herein are copyrighted by CCP hf. -

A FUTURISTIC PORTABLE DIY LAPTOP What We Stand For

The Android APK • SEGA Gaming on your ODROID • Linux Gaming Year One Issue #9 Sep 2014 ODROIDMagazineMagazine BUILD YOUR OWN WALL-E THE LOVABLE PIXAR ROBOT COMES TO LIFE WITH AN ODROID-U3 • BASH BASICS • FREEDOMOTIC 3D PRINT AN • WEATHER FORECAST ODROID-POWERED • 10-NODE U3 CLUSTER • ODROID-SHOW GARDENING SYSTEM 3DPONICS PLUS: A FUTURISTIC PORTABLE DIY LAPTOP What we stand for. We strive to symbolize the edge technology, future, youth, humanity, and engineering. Our philosophy is based on Developers. And our efforts to keep close relationships with developers around the world. For that, you can always count on having the quality and sophistication that is the hallmark of our products. Simple, modern and distinctive. So you can have the best to accomplish everything you can dream of. We are now shipping the ODROID U3 devices to EU countries! Come and visit our online store to shop! Address: Max-Pollin-Straße 1 85104 Pförring Germany Telephone & Fax phone : +49 (0) 8403 / 920-920 email : [email protected] Our ODROID products can be found at http://bit.ly/1tXPXwe EDITORIAL With the introduction of the ODROID-W and ODROID Weath- er Board, there have been several projects posted recently on the ODROID forums involving home automation, ambient lighting, and cool robotics. This month, we feature several of those projects, including predicting whether to go fishing this weekend, building a custom laptop case, taking care of your garden remotely, and building a faithful reproduction of everyone’s favorite robot, Wall-E! Hardkernel will be demonstrat- ing the new XU3 at ARM Techcon on Oc- tober 1st - 3rd, 2014 in San Jose, Califor- nia. -

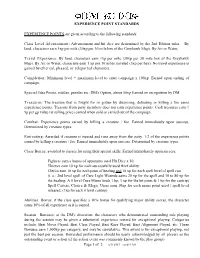

EXPERIENCE POINTS Are Given According to the Following Standards: Class Level Advancement: Advancement and Hit Dice Are Determin

EXPERIENCE POINT STANDARDS EXPERIENCE POINTS are given according to the following standards: Class Level Advancement: Advancement and hit dice are determined by the 2nd Edition rules. By land, characters earn 1xp per mile (30xp per 30 mile hex of the Greyhawk Map). By Air or Water, Travel Experience: By land, characters earn 1xp per mile (30xp per 30 mile hex of the Greyhawk Map). By Air or Water, characters earn 1 xp per 10 miles traveled (3xp per hex). No travel experience is gained by ethereal, phased, or teleported characters. Completion: Minimum level + maximum level to enter campaign x 100xp. Earned upon ending of campaign. Special:Idea Points, riddles, puzzles etc.:DM's Option, about 50xp Earned on recognition by DM Treasures: The treasure that is fought for or gotten by disarming, defeating or killing a foe earns experience points. Treasure from party members does not earn experience points. Cash treasures earn 1 xp per gp value (at selling price) earned when sold or carried out of the campaign. Combat: Experience points earned by killing a creature / foe. Earned immediately upon success. Determined by creature types. Retreating: Awarded if creature is injured and runs away from the party. 1/2 of the experience points earned by killing a creature / foe. Earned immediately upon success. Determined by creature types. Class Bonus: awarded to classes for using their special skills. Earned immediately upon success. Fighters earn a bonus of opponents total Hit Dice x 10. Thieves earn 10 xp for each successfully used thief ability. Clerics earn 10 xp for each point of healing and 10 xp for each spell level of spell cast (i. -

Dragon Magazine #103

D RAGON 1 18 SPECIAL ATTRACTION 48 UNEARTHED ARCANA additions and corrections New pieces of type for those who have the book 35 26 Publisher Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief OTHER FEATURES Kim Mohan 8 The future of the game Gary Gygax Editorial staff How well tackle the task of a Second Edition AD&D® game Patrick Lucien Price Roger Moore 12 Arcana update, part 1 Kim Mohan Art director and graphics Explanations, answers, and some new rules Roger Raupp All about Krynns gnomes Roger E. Moore Subscriptions 18 Finishing our series on the demi-humans of the DRAGONLANCE world Georgia Moore Advertising 26 A dozen domestic dogs Stephen Inniss Mary Parkinson Twelve ways to classify mans best friend Contributing editors The role of books John C. Bunnell Ed Greenwood 31 Reviews of game-related fantasy and SF literature Katharine Kerr This issues contributing artists 35 The Centaur Papers Stephen Inniss and Kelly Adams Robert Pritchard Everything two authors could think of about the horse-folk Larry Elmore Bob Maurus 58 The Wages of Stress Christopher Gilbert Roger Raupp How to handle obnoxious people and make it pay Tom Centola Marvel Bullpen David Trampier Ted Goff Joseph Pillsbury DEPARTMENTS 3 Letters 88 Convention calendar 93 Dragonmirth 4 World Gamers Guide 86 Gamers Guide 94 Snarfquest 6 The forum 89 Wormy COVER Robert Pritchards first contribution to our cover is an interesting piece of artwork and thats always the main factor in deciding whether or not to accept a painting to use. But Roberts choice of a title didnt hurt a bit.