Earthquake-Induced Disasters: Limiting the Damage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haiti Earthquake: Crisis and Response

Haiti Earthquake: Crisis and Response Rhoda Margesson Specialist in International Humanitarian Policy Maureen Taft-Morales Specialist in Latin American Affairs February 2, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41023 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Haiti Earthquake: Crisis and Response Summary The largest earthquake ever recorded in Haiti devastated parts of the country, including the capital, on January 12, 2010. The quake, centered about 15 miles southwest of Port-au-Prince, had a magnitude of 7.0. A series of strong aftershocks have followed. The damage is severe and catastrophic. It is estimated that 3 million people, approximately one third of the overall population, have been affected by the earthquake. The Government of Haiti is reporting an estimated 112,000 deaths and 194,000 injured. In the immediate wake of the earthquake, President Preval described conditions in his country as “unimaginable,” and appealed for international assistance. As immediate needs are met and the humanitarian relief operation continues, the government is struggling to restore the institutions needed for it to function, ensure political stability, and address long-term reconstruction and development planning. Prior to the earthquake, the international community was providing extensive development and humanitarian assistance to Haiti. With that assistance, the Haitian government had made significant progress in recent years in many areas of its development strategy. The destruction of Haiti’s nascent infrastructure and other extensive damage caused by the earthquake will set back Haiti’s development significantly. Haiti’s long-term development plans will need to be revised. The sheer scale of the relief effort in Haiti has brought together tremendous capacity and willingness to help. -

Adversus Paganos: Disaster, Dragons, and Episcopal Authority in Gregory of Tours

Adversus paganos: Disaster, Dragons, and Episcopal Authority in Gregory of Tours David J. Patterson Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Volume 44, 2013, pp. 1-28 (Article) Published by Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, UCLA DOI: 10.1353/cjm.2013.0000 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/cjm/summary/v044/44.patterson.html Access provided by University of British Columbia Library (29 Aug 2013 02:49 GMT) ADVERSUS PAGANOS: DISASTER, DRAGONS, AND EPISCOPAL AUTHORITY IN GREGORY OF TOURS David J. Patterson* Abstract: In 589 a great flood of the Tiber sent a torrent of water rushing through Rome. According to Gregory of Tours, the floodwaters carried some remarkable detritus: several dying serpents and, perhaps most strikingly, the corpse of a dragon. The flooding was soon followed by plague and the death of a pope. This remarkable chain of events leaves us with puzzling questions: What significance would Gregory have located in such a narrative? For a modern reader, the account (apart from its dragon) reads like a descrip- tion of a natural disaster. Yet how did people in the early Middle Ages themselves per- ceive such events? This article argues that, in making sense of the disasters at Rome in 589, Gregory revealed something of his historical consciousness: drawing on both bibli- cal imagery and pagan historiography, Gregory struggled to identify appropriate objects of both blame and succor in the wake of calamity. Keywords: plague, natural disaster, Gregory of Tours, Gregory the Great, Asclepius, pagan survivals, dragon, serpent, sixth century, Rome. In 589, a great flood of the Tiber River sent a torrent of water rushing through the city of Rome. -

Exposure and Vulnerability

Determinants of Risk: 2 Exposure and Vulnerability Coordinating Lead Authors: Omar-Dario Cardona (Colombia), Maarten K. van Aalst (Netherlands) Lead Authors: Jörn Birkmann (Germany), Maureen Fordham (UK), Glenn McGregor (New Zealand), Rosa Perez (Philippines), Roger S. Pulwarty (USA), E. Lisa F. Schipper (Sweden), Bach Tan Sinh (Vietnam) Review Editors: Henri Décamps (France), Mark Keim (USA) Contributing Authors: Ian Davis (UK), Kristie L. Ebi (USA), Allan Lavell (Costa Rica), Reinhard Mechler (Germany), Virginia Murray (UK), Mark Pelling (UK), Jürgen Pohl (Germany), Anthony-Oliver Smith (USA), Frank Thomalla (Australia) This chapter should be cited as: Cardona, O.D., M.K. van Aalst, J. Birkmann, M. Fordham, G. McGregor, R. Perez, R.S. Pulwarty, E.L.F. Schipper, and B.T. Sinh, 2012: Determinants of risk: exposure and vulnerability. In: Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation [Field, C.B., V. Barros, T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, D.J. Dokken, K.L. Ebi, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S.K. Allen, M. Tignor, and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA, pp. 65-108. 65 Determinants of Risk: Exposure and Vulnerability Chapter 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................67 2.1. Introduction and Scope..............................................................................................................69 -

Crisis Emergency Risk Communication (CERC) Introduction

CERC: Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication— Introduction 2018 Update 1 CERC: INTRODUCTION CS 290397-A CERC: Introduction This chapter will introduce: Crisis and Emergency Risk Communications (CERC) The Six Principles of CERC Terms Associated with CERC The Phases of a Crisis and the Communication Rhythm The Role of CERC What is Crisis and Emergency Risk Communications (CERC)? The Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) Crisis and pandemic illness, and earthquakes are just some Emergency Risk Communication (CERC) manual of the emergencies that we know could threaten provides an evidence-based framework and best any community at any time. Often, communicating practices for anyone who communicates on behalf information is the first and only resource available of an organization responding to a public health for responders to give affected communities at emergency.1 CERC is built around psychological the onset of an emergency. Through effective and communication sciences, studies in the field communication, we can impact how our community of issues management, and lessons learned from responds to and recovers from these potentially emergency responses. devastating emergencies. Emergencies can assault communities in an instant. Hurricanes, chemical releases, bombs, For the purpose of this manual, the term “emergency” describes any public health event or incident presenting risk to life, health, and infrastructure including natural, weather-related, and manmade destruction, infectious disease outbreaks, and exposure to harmful biological, radiological, and chemical agents. The term “emergency” encompasses “crises” and “disasters.” Why is CERC important? ready to act right away and need information on the “The right message at the right time from the situation and how to stay safe immediately. -

Psychological Issues in Escape, Rescue, and Survival in the Wake of Disaster

2008 Psychological Issues in Escape, Rescue, and Survival in the Wake of Disaster Report Submitted to the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, Pittsburgh Research Laboratory George S. Everly, Jr., PhD, ABPP Paul Perrin & George S. Everly, III Contents INTRODUCTION THE PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF CRISIS AND DISASTERS The Nature of Human Stress Physiology of Stress Psychology of Stress Excessive Stress Distress Depression Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Compassion Fatigue A Review of Empirical Investigations on the Mental Health Consequences of Crisis and Disaster Primary Victims/ Survivors Rescue and Recovery Personnel “RESISTANCE, RESILIENCE, AND RECOVERY” AS A STRATEGIC AND INTEGRATIVE INTERVENTION PARADIGM Historical Foundations Resistance, Resiliency, Recovery: A Continuum of Care Building Resistance Self‐efficacy Hardiness Enhancing Resilience Fostering Recovery LEADERSHIP AND THE INCIDENT MANAGEMENT AND INCIDENT COMMAND SYSTEMS (ICS) Leadership: What is it? Leadership Resides in Those Who Follow Incident Management Essential Information NIMS Components 1 Psychological Issues in Escape, Rescue, and Survival in the Wake of Disaster | George Everly, Jr. The Need for Incident Management Key Features of the ICS Placement of Psychological Crisis Intervention Teams in ICS Functional Areas in the Incident Command System Structuring the Mental Health Response Challenges of Rural and Isolated Response Caution: Fatigue in Incident Response Summary CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS REFERENCES APPENDIX A – Training resources in disaster mental health and crisis intervention APPENDIX B – Psychological First Aid (PFA) 2 Psychological Issues in Escape, Rescue, and Survival in the Wake of Disaster | George Everly, Jr. Introduction The experience of disaster appears to have become an expected aspect of life. Whether it is a natural disaster such as a hurricane or tsunami, or a human‐made disaster such as terrorism, the effects can be both physically and psychological devastating. -

DISASTER MANAGEMENT in a PANDEMIC 1 STEPS to FOLLOW for an EFFECTIVE How to Create an Emergency Operations Center (EOC) PANDEMIC RESPONSE 1

DISASTER MANAGEMENT TOOL DISASTER MANAGEMENT 15 IN A PANDEMIC In any serious disaster a gap develops between resource needs and resource availability. In a severe pandemic this gap will be much worse due to global supply chain disruptions or delays and the fact that governments and aid organizations PREPAREDNESS RESPONSE will be overwhelmed responding to all who need assistance at the same time. Your This tool will help you to: plan should assume that there will be little or no assistance coming from outside • Develop an organizational the municipality. structure to manage a pandemic It is of prime importance that the municipal leaders read, discuss, and study their at a municipal level national, regional/state, and district pandemic response plans to understand: • Assess needs, identify resources, • What plans are already in place plan, and implement the • What preparedness and response resources are available municipality’s response to a pandemic • How the municipal level plan fits into the national pandemic response structure Who will implement this tool: As municipal leaders, you will be responsible for keeping the population healthy, calm, and safe during the 6 to 12 weeks of each severe pandemic wave (remember • The municipal leadership team there could be as many as three waves). Your actions can determine whether there • Individuals responsible are many deaths or relatively few. for disaster response and implementation The most important goals of successful municipal pandemic management are to: What Needs to Be Done? • Have a strong enough organizational structure to manage a pandemic in the municipality No one will be able to prevent a • Continually assess needs, identify resources, plan the response, and severe pandemic from coming to implement the plan your municipality. -

Natural Disaster Emergency Planning and Preparedness Risk Bulletin

Natural disaster emergency planning and preparedness An Environmental Risk Toolkit AXA XL Environmental Risk Bulletin Be prepared. Natural Disaster Emergency Planning and Preparedness . 1 Disasters can happen at any time. Imagine that your business or facility is hit by a natural disaster, such as a hurricane, tornado, flood, earthquake or large wildfire. How will you ensure that your business quickly returns to normal operations and profitability? How will you protect your employees? One way to help do this is to create a Natural Disaster Preparedness and Response Plan. Both the final plan and the planning process are useful tools to respond to emergencies and to minimize costs and business interruptions. It can also be a strategic tool in business planning to ensure operational continuity. Being prepared and having a written plan should also help companies more effectively respond to any third party liabilities and claims that may arise from the surrounding community in the aftermath of a disaster. Why Plan for Natural Disasters? But why should we plan since natural disasters are rare? One of the primary reasons is potential cost savings to the affected business. Preparedness saves time and money by allowing a faster and more efficient resumption of routine business activities. Preparedness and periodic planning help businesses return to normal operation after a man-made or natural disaster. A disaster plan may also help enable a firm to stay in business and survive catastrophic events. According to the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), small businesses that don’t have a plan in place generally don’t survive after a disaster. -

The Institutional Causes of China's Great Famine, 1959–1961

Review of Economic Studies (2015) 82, 1568–1611 doi:10.1093/restud/rdv016 © The Author 2015. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of The Review of Economic Studies Limited. Advance access publication 20 April 2015 The Institutional Causes of China’s Great Famine, 1959–1961 Downloaded from XIN MENG Australian National University NANCY QIAN Yale University http://restud.oxfordjournals.org/ and PIERRE YARED Columbia University First version received January 2012; final version accepted January 2015 (Eds.) This article studies the causes of China’s Great Famine, during which 16.5 to 45 million individuals at Columbia University Libraries on April 25, 2016 perished in rural areas. We document that average rural food retention during the famine was too high to generate a severe famine without rural inequality in food availability; that there was significant variance in famine mortality rates across rural regions; and that rural mortality rates were positively correlated with per capita food production, a surprising pattern that is unique to the famine years. We provide evidence that an inflexible and progressive government procurement policy (where procurement could not adjust to contemporaneous production and larger shares of expected production were procured from more productive regions) was necessary for generating this pattern and that this policy was a quantitatively important contributor to overall famine mortality. Key words: Famines, Modern chinese history, Institutions, Central planning JEL Codes: P2, O43, N45 1. INTRODUCTION -

IFMSA Policy Document Disaster and Emergency Management

IFMSA Policy Document Disaster and Emergency Management Proposed by Team of Officials Adopted at the 69th IFMSA Online General Assembly August Meeting 2020 Policy Statement Introduction: Disaster and emergency management is an ever-evolving field that aims to effectively address disasters and emergencies for the sake of a better future. It emphasizes the critical importance of prevention, preparedness, response and recovery, to mitigate the consequences, save lives and protect health. This policy urges members to work together and assist the appropriate response in order to reduce the negative social, economic and health impact locally, nationally and globally. IFMSA position: The International Federation of Medical Students Associations (IFMSA) recognizes the global burden of disasters and emergencies and calls for the implementation of effective strategies to promote risk reduction and management. IFMSA firmly believes that along with future healthcare professionals, global action is needed. Furthermore, IFMSA recognizes the importance of disaster and emergency management and demands close cooperation and coordination between the stakeholders to improve disaster resilience. Call to Action: Therefore, IFMSA calls on: Governments to: • Implement the Sendai Framework Convention for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR). • Create national coordination clusters and policies with collaboration across all sectors for people centered disaster & emergency management. • Adopt inclusive and sustainable disaster management plans, including capacity-building -

Glossary of Terms

page GLO-1 Glossary of Terms Words, phrases, abbreviations, and acronyms relevant to emergency management should be defined. Many terms in emergency management have special meanings, so it is important to establish precise definitions. Such definitions allow the users of the EOP to share an understanding of the EOP. American Red The American Red Cross is a humanitarian organization, led by volunteers, that Cross provides relief to victims of disasters and helps people prevent, prepare for, and respond to emergencies. It does this through services that are consistent with its Congressional Charter and the Principles of the International Red Cross Movement. Attack A hostile action taken against the United States by foreign forces or terrorists, resulting in the destruction of or damage to military targets, injury or death to the civilian population, or damage or destruction to public and private property. Checklist Written (or computerized) enumeration of actions to be taken by an individual or organization, meant to aid memory rather than provide detailed instruction. Chief The official of the community who is charged with authority to implement and Executive administer laws, ordinances, and regulations for the community. He or she Official may be a mayor, city manager, etc. Community A political entity which has the authority to adopt and enforce laws and ordinances for the area under its jurisdiction. In most cases, the community is an incorporated town, city, township, village, or unincorporated area of a county. However, each State defines its own political subdivisions and forms of government. Contamination The undesirable deposition of a chemical, biological, or radiological material on the surface of structures, areas, objects, or people. -

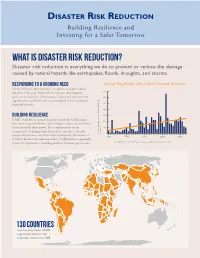

Disaster Risk Reduction Building Resilience and Investing for a Safer Tomorrow

DISASTER RISK REDUCTION Building Resilience and Investing for a Safer Tomorrow What is Disaster Risk Reduction? Disaster risk reduction is everything we do to prevent or reduce the damage caused by natural hazards like earthquakes, floods, droughts, and storms. Responding to a Growing Need Global Population Affected by Natural Disasters Natural disasters affect hundreds of millions of people around 700 the globe every year. With each new disaster, development gains are threatened as infrastructure is destroyed and economic 600 opportunities and livelihoods are interrupted or lost, leading to increased poverty. 500 400 Building Resilience 300 USAID responds to natural disasters around the world, saving 200 lives, protecting livelihoods, and working to reduce the economic losses caused by these events. Just as importantly, we are 100 committed to helping people lessen their exposure to hazards, Reported Number of People Affected Affected Reported Number of People (in Millions) 0 prepare for disasters, and better withstand shocks. The lessons of 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 USAID’s disaster risk reduction efforts worldwide have repeatedly shown the importance of building resilience in hazard-prone areas. Source: EM-DAT - The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database, www.emdat.be, April 2014 130 COUNTRIES have benefited from USAID- supported disaster risk reduction efforts since 1989. USAID’S DISASTER RISK REDUCTION PROGRAMS SAVE LIVES Strengthening Early Warning Since 1989, we have helped establish 17 global, regional, or national early warning systems for drought, volcanoes, cyclones, and floods. These early warning systems work. For example, in 2013, warnings issued days prior to Cyclone Phailin’s arrival in India gave local authorities time to coordinate preparedness measures, including the evacuation of 1 million people living in coastal areas. -

Causes and Lessons of the Mexican Peso Crisis

Causes and Lessons of the Mexican Peso Crisis Stephany Griffith-Jones IDS, University of Sussex May 1997 This study has been prepared within the UNU/WIDER project on Short- Term Capital Movements and Balance of Payments Crises, which is co- directed by Dr Stephany Griffith-Jones, Fellow, IDS, University of Sussex; Dr Manuel F. Montes, Senior Research Fellow, UNU/WIDER; and Dr Anwar Nasution, Consultant, Center for Policy and Implementation Studies, Indonesia. UNU/WIDER gratefully acknowledges the financial contribution to the project by the Government of Sweden (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency - Sida). CONTENTS List of tables and charts iv Acknowledgements v Abstract vi I Introduction 1 II The apparently golden years, 1988 to early 1994 6 III February - December 1994: The clouds darken 15 IV The massive financial crisis explodes 24 V Conclusions and policy implications 31 Bibliography 35 iii LIST OF TABLES AND CHARTS Table 1 Composition (%) of Mexican and other countries' capital inflows, 1990-93 8 Table 2 Mexico: Summary capital accounts, 1988-94 10 Table 3 Mexico: Non-resident investments in Mexican government securities, 1991-95 21 Table 4 Mexico: Quarterly capital account, 1993 - first quarter 1995 (in millions of US dollars) 22 Table 5 Mexican stock exchange (BMV), 1989-1995 27 Chart 1 Mexico: Real effective exchange rate (1980=100) 7 Chart 2 Current account balance (% of GDP) 11 Chart 3 Saving-investment gap and current account 12 Chart 4 Stock of net international reserves in 1994 (in millions of US dollars) 17 Chart 5 Mexico: Central bank sterilised intervention 18 Chart 6 Mexican exchange rate changes within the exchange rate band (November 1991 through mid-December 1994) 19 Chart 7 Mexican international reserves and Tesobonos outstanding 20 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank UNU/WIDER for financial support for this research which also draws on work funded by SIDA and CEPAL.