Self-Study Report Submitted to NWCCU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monday, May 22, 2017 Dailyemerald.Com

MONDAY, MAY 22, 2017 DAILYEMERALD.COM ⚙ MONDAY 2017 SHASTA WEEKEND 2016 TRUMP MAY AXE STUDENT DEBT FORGIVENESS PROGRAM WRAPPING UP LAST WEEK’S NEWS THE WESTERN WORLD’S TEACHING IS RACIST OmniShuttle 24/7 Eugene Airport Shuttle www.omnishuttle.com 541-461-7959 1-800-741-5097 CALLING ALL EXTROVERTS! EmeraldEmerald Media Media Group Group is is hiring hiring students students to to join join ourour Street Street TeamTeam. Team winter Getfall paidterm. term. to Get have Get paid paidfun to handing tohave have fun funouthanding handingpapers out to out papers fellow papers tostudents. fellowto fellow students. students. Apply in person at Suite 300 ApplyApply in in person person at at our our office office in in the the EMU EMU, Basement Suite 302 or email [email protected] oror email email [email protected] [email protected] June 1st 2017 EmeraldFest.com PAGE 2 | EMERALD | MONDAY, MAY 22, 2017 NEWS NEWS WRAP UP • UO shut down its websites for maintenance; more downtime set for the future. Monday • The Atlantic published UO professor Alex Tizon’s posthumous story on his family’s slave. The story was received with some controversy and sent a shock through the Twitter-sphere. Tizon, a Pulitzer Prize win- ner, died in March at age 57. Tuesday Betsey DeVos, the Secratary of Education, might cut a student debt forgiveness program in announcement set for next week. (Creative Commons) Student debt forgiveness program may get axedaxed by Trump administration • Director of Fraternity and Sorority Life Justin Shukas announced his resignation. ➡ • The School of Journalism and Communica- WILL CAMPBELL, @WTCAMPBELL tion announced its budget plan. -

Full Applications Catalog

Applications Catalog Service Owner Title Vendor Primary Category Annual Cost Recommendation JSMA Admin Operations Mobius Support Axiell ALM Canada Inc Database/data/analytics $ 5,099.00 Project be formed Business Affairs Office 1099 Pro 1099 Pro Inc Finance and Business Processing $ 4,997.00 Educational and Community Supports 123RF.COM 123RF.COM Graphics $ 1,470.00 UO Libraries 1PASSWORD FS *1PASSWORD Security / Identity $ 49.99 IS Data Management 24 SecureCRT +^SecureFX VanDyke Software Systems/repair/utilities $ 152.50 IS Middleware and Application Devmt 25 SecureCRT +^SecureFX VanDyke Software Systems/repair/utilities $ 152.50 DOS Operations 3rd Millennium 3rd Millennium Assessment management $ - Rsch Physics/MSI Rsch Projects 500 lhz instrument Zurich Instruments AG Research $ 5,980.00 College of Design A&E Imaging Inc A&E Imaging Inc Printing services $ 1,345.50 UESS AEC Operations Accommodation, Appointment & Case Mgmt. (AIM) Accessible Information Management LLC CRM $ 10,524.80 Project in proccess Business, Lundquist College of Accounting Scholarship Administration Developed in house Student success $ - Business, Lundquist College of Accounting Scholarship Application Developed in house Student success $ - UC General Operations Acronis CDW Government Inc Database/data/analytics $ 1,036.80 FASS IT AcSELerator SEL Facilities / building maintenance & management$ 1,200.00 EM Strategic Communications Admissions Material Request UO Student success $ - EMU KWVA Radio Adobe Audition/Suite Adobe Broadcasting $ 923.40 Business, Lundquist -

Impact Report

2015 –16 ERB MEMORIAL UNION IMPACT REPORT 1 Welcome to the new EMU After a decade of planning and nearly three years of construction, we proudly opened the doors to the new EMU last month. Literally thousands of people, from the student voters who approved project funding in 2012, to dozens of stakeholders involved in every step of devel- opment, have helped make our dream of a new student union a reality. Together, we’ve worked hard to create a building that meets the needs of our diverse campus and melds prominent building features with state of the art design. Now that early feedback is in, we think it’s safe to say that we’ve succeeded in creating a beautiful gathering place and a home for exceptional student experiences that will serve the University of Oregon for years to come. We’ve only been open for a short time, but it didn’t take long for students to discover a terrific new dining option, settle in to an out-of-the way study nook, or find their way back to a favorite program. I’ve had the pleasure of watching many first-time visitors explore our beautiful new spaces, and I am thrilled, humbled, and inspired to hear such great pride and enthusiasm in their comments. Although work on the 210,000 sq. ft. building will continue through next TABLE OF CONTENTS fall, we are delighted to be back in the Erb Memorial Union serving the UO campus and community as we have for the past 65 years. I want to 4 Facilities sincerely thank our UO students and stakeholders for your vision, support, and patience, and to invite you to visit and help celebrate our beautiful 8 Programs new EMU. -

Erb Memorial Union (The EMU) Historic Building Name: Donald M

HISTORIC RESOURCE SURVEY FORM University of Oregon Cultural Resources Survey Eugene, Lane County, Oregon Summer 2006 RESOURCE IDENTIFICATION Current building name: Erb Memorial Union (the EMU) Historic building name: Donald M. Erb Memorial Student Union, Student Union, Building 23 Building address: 1222 East 13th Ave. Ranking: Secondary ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION Architectural style classification: International Modernism (1950), Brutalism (1972) Building plan (footprint shape): Irregular Number of stories: 3 Foundation material(s): Concrete Primary exterior wall material: Brick Secondary exterior wall material: Cut Stone and Concrete Roof configuration/type: Flat Primary roof material: BUR (Built Up Roofing) Primary window type: Fixed wood frame with 8 and 12 lights and steel single-pane casement Primary window material: Wood Decorative features and materials: Marble at main entrance, stained glass over entry, brick and travertine fireplace Landscape features: Brick planters, EMU lawn on the east side with established trees including the Douglas Fir “Moon Tree.” The Douglas Fir at the northeast corner of the EMU lawn grew from a seed that was among four fir seeds carries to the moon aboard Apollo XIV in 1971 by Astronaut Stuart Roosa. In 1978 the seedling was planted where Willamette Hall now stands; it was transplanted in 1987 to accommodate construction of the additions to the Science complex. Associated resources: Amphitheater Green, 13th Ave Axis, University Street Axis, Straub Hall Green Comments: The original portion of the EMU is a brick building with many different types of wooden and metal framed windows. It has a large concrete amphitheatre on the west side of the building and a green lawn on the east side of the building. -

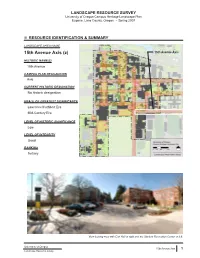

15Th Avenue Axis (Z) 15Th Avenue Axis

LANDSCAPE RESOURCE SURVEY University of Oregon Campus Heritage Landscape Plan Eugene, Lane County, Oregon • Spring 2007 n RESOURCE IDENTIFICATION & SUMMARY LANDSCAPE AREA NAME 5th Avenue Axis (z) 5th Avenue Axis HISTORIC NAME(S) 15th Avenue CAMPUS PLAN DESIGNATION Axis CURRENT HISTORIC DESIGNATION No historic designation ERA(S) OF GREATEST SIGNIFICANCE Lawrence/Cuthbert Era Mid-Century Era LEVEL OF HISTORIC SIGNIFICANCE Low LEVEL OF INTEGRITY Good RANKING Tertiary View looking west with Earl Hall at right and the Student Recreation Center at left. University of Oregon 15th Avenue Axis Landscape Resource Survey Landscape Resource Survey 5TH AVENUE AXIS LANDSCAPE AREA SITE MAP — Highlighting existing elements from the period of significance (1876-1974). Some of the Douglas firs planted Crimson King Norway Retaining wall appeared during near the Onyx Intersection may maples were planted during the Lawrence/Cuthbert Era date back to the Inception Era the Lawrence/Cuthbert Era Straub Hall Green Earl Complex Living Learning Walton Complex Straub Hall Center 5th Avenue Student Agate Street University Street Recreation Hayward Field Center * note: Period of Significance refers to the project period of 1876-1974 University of Oregon 15th Avenue Axis Landscape Resource Survey Landscape Resource Survey 5TH AVENUE AXIS SUMMARY OF EXISTING HISTORIC FEATURES Most of the historic features associated with the Inception Era, and the large retaining wall of the 15th Avenue Axis are street trees. The row of SRC field and the Crimson King Norway maples Douglas firs between Straub Hall and University are from the Lawrence/Cuthbert Era. The street Street, and the row of Norway maples in front of has been associated with Hayward Field since the the Student Recreation Center’s (SRC) outdoor 1920s, though the north end of that facility was playing field are all from the eras of significance. -

Invitation to Bid

INVITATION TO BID EMU Renovation & Addition - Bid Package 3 May 23, 2014 University of Oregon Lewis Project No PC13704 Bid Package #3 - Amendment #1 Page 1 of 1 Clarifications to Instructions to Bidders Amendment #1 UO Erb Memorial Union Expansion and Renovation – Bid Package #3 North Wing - Site Work, Foundation, and Structure Eugene, Oregon May 30, 2014 Clarifications and Information . Entire Invitation to Bid (All Bidders): • Invitation to Bid and Instruction to Bidders – See attached Bid Package, dated May 23, 2014. • A mandatory pre-bid conference for the concrete foundations/structures and wood framing scopes of work will be held on Monday, June 9th, at 1:00pm at the project location on the University of Oregon Campus (Job Trailer is located at approximately 1222 E. 13 th Ave, Eugene, OR 97403). Erb Memorial Union Renovation and Expansion Bid Package #3 – North Wing – Site Work, Foundation, and Structure University of Oregon EUGENE, OREGON INVITATION TO BID AND INSTRUCTION TO BIDDERS May 23, 2014 INVITATION TO BID EMU Renovation and Addition – Bid Package 3 May 23, 2014 University of Oregon Lewis Project No. PC13704 Table of Contents Page 1 of 2 INVITATION TO BID TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Advertisement for Bid II. Instructions to all Bidders Section 1 Bid Documents Section 2 Form of Proposal Section 3 Bid Date Section 4 Pre-Bid Conference Section 5 Contact for Information Section 6 Document Review Section 7 Protests Section 8 Bond Section 9 Acceptance of Bids Section 10 Clarifications Section 11 General Bidding Requirements Section 12 Specific Bidding Requirements III. Trade Specific Instructions to Bidders ITB Bid Package # 3.01 - Earthwork, Utilities, Site Demo, Excavation ITB Bid Package # 3.02 - Concrete Structure ITB Bid Package # 3.03 - Structural Steel ITB Bid Package # 3.04 - Elevators ITB Bid Package # 3.05 - Wood Framing - Draft IV. -

Where the Heart IS PAGE 2 for Eugene Residents, PULSE Communal Living Is More Applications Than Just Sharing Space

The independent student newspaper at the University of Oregon dailyemerald.com SINCE 1900 | Volume 109, Issue 53 | Thursday, October 25, 2007 OPINION IN MY OPINION Law school Campus Greeks should start acting Greek. WHERE THE HEART IS PAGE 2 For Eugene residents, PULSE communal living is more applications than just sharing space MIKE O’BRIEN News Reporter in flux llen Hancock eats well. His big orange house in Eugene’s South University neighbor- hood boasts quite an impres- nationwide Asive garden — greens, herbs, nuts, peaches, even passion fruit — and on Fewer students are applying to law ‘ROCKY HORROR’ any given night, the fragrant aroma of The quirky musical is herbs and fresh produce wafts through schools across the U.S., but UO Law back again this year. the kitchen. Hancock doesn’t like to applications are steadily rising PAGE 5 cook every night and luckily for him, he only has to do it once a week. Hancock lives in Du•má, named for ALLIE GRASGREEN the Kalapuya word for “home,” with News Reporter nine other people as part of an urban While law schools nationwide are in the intentional-living community. midst of an applicant rate downturn, the num- Commonly referred to as communes, ber of University School of Law applicants is intentional-living communities are most steadily increasing. often associated with the hippie move- Kaplan Test Prep and Admissions’ annual ment of the late 1960s and early 1970s. survey of law schools showed, as expected, “A lot of people are not very much the number of overall applicants decreased of aware of how widespread it is,” said last year by 7.4 percent. -

Strfkr to Perform at Art Alive Emu Opera in Eugene Endures Little Funding

MONDAY, MAY 14, 2018 DAILYEMERALD.COM MONDAY BASEBALL ROUTS UTAH 43 SPORTS PG 17 WHOOPING COUGH STRIKES CAMPUS NEWS PG 3 KEEPING THE PREVIEW: STRFKR TO PERFORM AT ART ALIVE EMU OPERA IN EUGENE ENDURES LITTLE FUNDING, low staffing, and falling audience numbers A&C PG 1011 to sustain and modernize a historic artform. OmniShuttle 24/7 Eugene Airport Shuttle INVEST IN YOUR FUTURE www.omnishuttle.com 541-461-7959 APPLY TODAY 1-800-741-5097 BEST HANGOVER BREAKFAST Graduate Programs 14 STRAIGHT YEARS! BREAKFAST ALL DAY • M.A. Criminal Justice 1689 Willamette | 541-343-1542 • M.A. Interpreting Studies 7am - 2pm Every day • M.A. Teaching (Initial License) featuring • M.M. Contemporary Music • M.S. in Education see our full menu online: brailseugene.com • M.S. in Ed. Deaf and Hard of Hearing Education • M.S. in Ed. Information Technology • M.S. in Ed. Special Education • M.S. Management and THE Information Systems GEOG Geography • M.S. Rehabilitation and Mental Health Counseling WHY • Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) Specialization • Elementary Mathematics OF Instructional Leader Specialization/ Certificate • ESOL Endorsement/Certificate • Instructional Design Certificate WHERE • Reading Endorsement/Certificate wou.edu/grad whyofwhere geography.uoregon.eduwhyofwhere Questions: TOGETHER WE [email protected] SUCCEED PAGE 2 | EMERALD | MONDAY, MAY 14, 2018 NEWS UO Health Center. (Emerald Archives) TWO CASES OF WHOOPING COUGH FOUND ON CAMPUS BY HANNAH KANIK • TWITTER HANNAH_KANIK “It was just like having allergies,” Leonie Way, Whooping cough is diagnosed through a diagnosed two to three weeks after symptoms who was diagnosed with whooping cough last nose-swab that tests for the bacteria Bordetella present themselves because after that time, the week, said. -

What Every Duck Needs to Know

2015 DuckWHAT EVERY DUCK NEEDS Life TO KNOW YOU’RE A DUCK NOW. YOU’RE ONE OF US. SO, WHAT’S NEXT? Within these pages you’ll find everything you need to go from a fledgling duckling to a bonafide mallard. ➜ FOOTBALL TICKETS ➜ GREEK LIFE ➜ MEAL PLANS ➜ BUYING BOOKS ➜ OUTDOOR PROGRAM ➜ AND MORE... content sponsored by: NEW STUDENT HOUSING OPENING FALL 2015 SIGN A LEASE IN A 4 BED + 4 BATH A OR B FLOOR PLAN & SAVE VISIT 2125FRANKLIN.COM TO SEE OUR CURRENT LEASING SPECIALS + SAVE $150 WITH ZERO DOWN HOW DO WE COMPARE? MEAL PLAN REQUIRED? SUMMER INCLUDED? TOTAL 2125 FRANKLIN shared bed + shared bath NO YES $6,588 RESIDENCE HALLS shared bed + shared bath YES NO $11,430-$16,645* 2125 FRANKLIN private bed + private bath NO YES $7,908-$8,628 RESIDENCE HALLS private bed + private or shared bath YES NO $12,582-$19,786* HARD HAT TOURS — EVERY TUES. & WED. FROM 4-5PM TOURS BEGIN AT THE 2125 FRANKLIN LEASING OFFICE & ARE LIMITED TO 10 PEOPLE AT A TIME Rates & fees are subject to change. Limited time only. While supplies last. Total includes 16 meals per week. Total does not include cost for summer. Information accurate as of 5/19/15 — https:housing.uoregon.edu COUPON COBURG RD. Student Special Oakway Golf Course 2000 Cal Young Rd CAL YOUNG RD. 50% OAKWAY RD. OFFwith valid Student ID COBURG RD. $9 for Ferrry Street Bridge 18 holes Willamette River $5 for BROADWAY FRANKLIN BLV 9 holes D OAKWAY GOLF COURSE University of Oregon Bring entire ad to course. -

University of Oregon

A B C D E F G H I J K L M To Autzen Stadium Complex & Riverfront A U T Z E N S T A D I U M C O M P L E X 11 UNIVERSITY OF OREGON Fields 11 MARTIN LUTHER KING JR BLVD E U G E N E Hatfield-DWowlin Football Complex i l Practice Fields l PK Casanova a Amutzen Park LE Athletic Campus Operations O Brooe H kst A R Mosho Field t ZIRC MIL R fsky e Office LRACE DR IS Sports Central Fine PK Randy and 10 W Stadium 10 Power Arts Y Susie Station Wilkinson Pape CRomplex Mill Millrace Studios i v race House Innovation e To Barnhart, Studios r 10th & Mill Building, Woodshop Riverfront Research Park Center and Baker Downtown Center Urban Y F W To Main Campus R K EAST 11TH AVE ANK Farm 0 600 Feet # LIN P BLV Millrace 9 D T N 9 N CMER Millrace 4 O Robinson R F Theatre Villard R E McKenzie V MILLER THEATRE COMPLEX I Lawrence R Franklin Hope Cascade Building Theatre GARD Annex EN AVE EAST 12TH AVE Deady 8 Onyx Bridge Lewis T 8 Streisinger S Pacific Science UO Allen Integrative S Computing Cascade Library S Annex Klamath Science O M PeaceHealth University District Lillis L O K E Y S C I E N C E C O M P L E X T y S s g LILLIS BUSINESS COMPLEX e D t o Huestis Jaqua R l Willamette Lokey u Oregon A o T Chiles h Academic L F L S n R I Duck c A Fenton Friendly Columbia Laboratories NK V Peterson Anstett a L T s Center I N BL U Store c V e D 7 l 7 Information N o D L EAST 13TH AVE (restricted access) (limited vehicle access) T ^ Kiosk EAST 13TH AVE Rainier A V S W H University Condon Chapman C Watson Burgess Ford E Health, E B Johnson Carson oyn llier Alumni To B -

Advising Workshops 2:00 P.M.–2:20 P.M

2016–17 SCHEDULE TWO-DAY PROGRAM TWO-DAY PROGRAM (Continued from previous page) TIMES TITLE LOCATION TIMES TITLE LOCATION 8:00 a.m.–9:00 a.m. Student Check-In 2:00 p.m.–2:20 p.m. Interest Session #3a and #3b: Lifehacks for College 104 Erb Memorial Union | Coquille Room 9:00 a.m.–9:30 a.m. Opening Session 2:30 p.m.–2:50 p.m. 9:30 a.m.–10:00 a.m. Flock Meeting 2:00 p.m.–2:20 p.m. Interest Session #3a and #3b: Residence Life 119 Erb Memorial Union | Diamond Lake Room 10:00 a.m.–10:30 a.m. Faculty Perspectives 2:30 p.m.–2:50 p.m. 10:40 a.m.–11:55 a.m. Academic Advising Workshops 2:00 p.m.–2:20 p.m. Interest Session #3a and #3b: Technology on Campus 23 Erb Memorial Union | Mallard Room Noon–12:50 p.m. Lunch Follow your SOSer 2:30 p.m.–2:50 p.m. Wellness Program Campus Tour Meet at Erb Memorial Union Lobby, Ground Floor 1:00 p.m.–2:50 p.m. DAY TWO 2:00 p.m.–2:50 p.m. Your Story, Our Story Residence Hall Tours Global Scholars Hall Lobby INTEREST SESSIONS Campus Jobs and Career Readiness 10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. Check Out Living-Learning Center Service Desk DAY ONE 3:00 p.m.–4:45 p.m. “It Can’t Be Rape” 3:00 p.m.–5:00 p.m. Tour of Autzen Stadium Meet outside the Jaqua Academic Center 4:45 p.m.–5:15 p.m. -

Erb Memorial Union Post-Occupancy Study Place-Based Belonging & Connections: Favorite EMU Places

Erb Memorial Union Post-Occupancy Study Place-Based Belonging & Connections: Favorite EMU Places Laurie Woodward, Ph.D., Director [email protected] Mathieu Wilson, Undergraduate Student, Student Life Emerging Leader [email protected] Erb Memorial Union Division of Student Life Renée Delgado-Riley, Ph.D., Director [email protected] Brian Clark, Ph.D., Assistant Director [email protected] Office of Assessment and Research Division of Student Life Background The recently-renovated Erb Memorial Union (EMU) is the heart of our campus, serving the entire University of Oregon (UO) community. No UO graduate has ever majored in student unions, but it would be hard to find a Duck whose college experience wasn’t somehow shaped by the EMU. Since it first opened in 1950, the EMU has provided a place to study, eat, and gather. However, for a residential campus, a student union also means much more. It is a vital part of the university’s vision to create a vibrant community of scholars. Because the EMU has been revitalized through recent renovations, is the heart of the UO campus, and is the top place on campus where students feel like they belong, the present research was designed to explore how students use and what students think and feel about the places that comprise the union. Place-Based Belonging Through the present research as well as the Student Wellbeing and Success Initiative (SWaSI) research program, the Office of Assessment & Research (OAR) within the Division of Student Life is beginning to explore a novel aspect of belongingness. OAR is calling it place-based belonging to represent the idea that people’s sense of belonging (i.e., of fitting in and being connected to others) has much to do with the physical places where human interaction occurs.