Wrangell Island Project Draft Environmental Impact Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alaska's Nonresident Anglers, 2009-2013

Alaska’s Nonresident Anglers, 2009‐2013 For: Alaska Department of Fish and Game By: Southwick Associates October 2014 PO Box 6435 Fernandina Beach, FL32035 Tel (904) 277‐9765 www.southwickassociates.com Contents List of Tables .................................................................................................................................................................. ii List of Charts .................................................................................................................................................................. ii Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of Findings ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Gender and Age ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Country and State of Residence .................................................................................................................................... 3 Overview of Nonresident Anglers’ Country and State of Residence ......................................................................... 3 Country of Residence ................................................................................................................................................ -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Wolf-Sightings on the Canadian Arctic Islands FRANK L

ARCTIC VOL. 48, NO.4 (DECEMBER 1995) P. 313–323 Wolf-Sightings on the Canadian Arctic Islands FRANK L. MILLER1 and FRANCES D. REINTJES1 (Received 6 April 1994; accepted in revised form 13 March 1995) ABSTRACT. A wolf-sighting questionnaire was sent to 201 arctic field researchers from many disciplines to solicit information on observations of wolves (Canis lupus spp.) made by field parties on Canadian Arctic Islands. Useable responses were obtained for 24 of the 25 years between 1967 and 1991. Respondents reported 373 observations, involving 1203 wolf-sightings. Of these, 688 wolves in 234 observations were judged to be different individuals; the remaining 515 wolf-sightings in 139 observations were believed to be repeated observations of 167 of those 688 wolves. The reported wolf-sightings were obtained from 1953 field-weeks spent on 18 of 36 Arctic Islands reported on: no wolves were seen on the other 18 islands during an additional 186 field-weeks. Airborne observers made 24% of all wolf-sightings, 266 wolves in 48 packs and 28 single wolves. Respondents reported seeing 572 different wolves in 118 separate packs and 116 single wolves. Pack sizes averaged 4.8 ± 0.28 SE and ranged from 2 to 15 wolves. Sixty-three wolf pups were seen in 16 packs, with a mean of 3.9 ± 2.24 SD and a range of 1–10 pups per pack. Most (81%) of the different wolves were seen on the Queen Elizabeth Islands. Respondents annually averaged 10.9 observations of wolves ·100 field-weeks-1 and saw on average 32.2 wolves·100 field-weeks-1· yr -1 between 1967 and 1991. -

Southeast Alaska Mid-Region Access Port and Ferry Terminal Technical Memorandum

S A M-R A P Ferr T T M Prepared for Fr Highw An Through R Pecci Associates, I. 825 Custer Avenue Helena, Montana 59604 (406)447-5000 www.rpa-hln.com Prepared by T Gos Associates, I. 1201 Western Avenue, Suite 200 Seattle, WA 98101 www.glosten.com Pametri, I. 700 NE Multnomah, Suite 1000 Portland, OR 97232-4110 T. 503.233.2400 F, 503.233.4825 www.parametrix.com CITATION The Glosten Associates, Inc., Parametrix, Inc. 2011. Southeast Alaska Mid-Region Access Port and Ferry Terminal Technical Memorandum. Prepared by The Glosten Associates, Inc., Seattle, Washington, Parametrix, Inc., Portland, Oregon. April 2011. Port and Ferry Terminal Technical Memorandum TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... ES-1 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Purpose of the Mid-Region Access Study ......................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Southeast Alaska Mid-Region Access Study Corridors ..................................................... 1-3 1.2.1 Bradfield Canal Corridor ....................................................................................... 1-3 1.2.2 Stikine River Corridor ........................................................................................... 1-5 1.2.3 Aaron Creek Corridor............................................................................................ 1-5 1.3 Characteristics -

And Peary Caribou (Rangifer Tarandus Pearyi) on Prince of Wales and Somerset Islands, August 2016 Morgan L

Distribution and abundance of muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) and Peary caribou (Rangifer tarandus pearyi) on Prince of Wales and Somerset Islands, August 2016 Morgan L. Anderson ᒧᐊᒐᓐ ᐋᓐᑐᕐᓴᓐ Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut, Igloolik, NU, [email protected] 867-934-2175 ᓂᕐᔪᑎᓂᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᖅᑎ ᖁᑦᑎᒃᑐᒥ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᒥ, ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ ᐆᒪᔪᕐᓂᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᖅᑎᒃᑯᑦ, ᓄᓇᕗᒻ ᒐᕙᒪᒃᑯᖏᑦ ᑎᑎᖅᑲᒃᑯᕕᐊ 209 ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒃ ᓄᓇᕗᑦ X0A 0L0 INTRODUCTION RESULTS MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS • Peary caribou and muskoxen are the only ungulates inhabiting the Muskoxen have declined slightly but remain at high Queen Elizabeth Islands. • Both are important sources of country food and cultural persistence densities. for local communities. Resolute , Taloyoak, and sometimes Gjoa Haven • The muskox population has declined since the 1990s, but it is still • The survey provided a population estimate of 3,052± SE 440 muskoxen harvest from Prince of Wales and Somerset islands. at high density and could support more harvest than is currently on Prince of Wales and Somerset islands (including smaller satellite • Severe winter weather (ground-fast ice ) restricts access to forage and taken, although there is no Total Allowable Harvest (TAH) on MX- islands), with 1,569 ± SE 267 on Prince of Wales, Pandora, Prescott, and causes sporadic die-off events.1, 2, 3 06. Russell islands, and 1,483 ± SE 349 muskoxen on Somerset Island. • The islands were previously occupied by 5,000 Peary caribou, which • Current muskox harvest does not fill the previous TAH (20 tags • The previous survey in 2004 estimated 2,086 muskoxen on Prince of allocated to Resolute, removed in fall 2015) annually for MX-06.15 migrated between Prince of Wales, Somerset, and smaller satellite Wales/Russell islands (1,582-2,746, 95% CI) and 1,910 muskoxen on 4 5 • The drastic decline in Baffin Island caribou over recent years has islands, and the Boothia Peninsula, but the population crashed to Somerset Island (962-3,792 95% CI) very low levels in the 1980s 6, 7and had not recovered as of the most limited harvest opportunities on Baffin Island. -

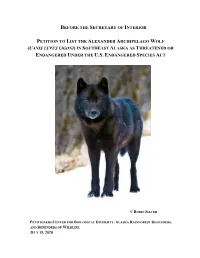

Petition to List the Alexander Archipelago Wolf in Southeast

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE ALEXANDER ARCHIPELAGO WOLF (CANIS LUPUS LIGONI) IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © ROBIN SILVER PETITIONERS CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS, AND DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE JULY 15, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Siekaniec, Alaska Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road Anchorage, AK 99503 [email protected] PETITIONERS Shaye Wolf, Ph.D. Larry Edwards Center for Biological Diversity Alaska Rainforest Defenders 1212 Broadway P.O. Box 6064 Oakland, California 94612 Sitka, Alaska 99835 (415) 385-5746 (907) 772-4403 [email protected] [email protected] Randi Spivak Patrick Lavin, J.D. Public Lands Program Director Defenders of Wildlife Center for Biological Diversity 441 W. 5th Avenue, Suite 302 (310) 779-4894 Anchorage, AK 99501 [email protected] (907) 276-9410 [email protected] _________________________ Date this 15 day of July 2020 2 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Alaska Rainforest Defenders, and Defenders of Wildlife petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”), to list the Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) in Southeast Alaska as a threatened or endangered species. -

THE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS: THEIR PEOPLE and NATURAL HISTORY

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WAR BACKGROUND STUDIES NUMBER TWENTY-ONE THE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS: THEIR PEOPLE and NATURAL HISTORY (With Keys for the Identification of the Birds and Plants) By HENRY B. COLLINS, JR. AUSTIN H. CLARK EGBERT H. WALKER (Publication 3775) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION FEBRUARY 5, 1945 BALTIMORE, MB., U„ 8. A. CONTENTS Page The Islands and Their People, by Henry B. Collins, Jr 1 Introduction 1 Description 3 Geology 6 Discovery and early history 7 Ethnic relationships of the Aleuts 17 The Aleutian land-bridge theory 19 Ethnology 20 Animal Life of the Aleutian Islands, by Austin H. Clark 31 General considerations 31 Birds 32 Mammals 48 Fishes 54 Sea invertebrates 58 Land invertebrates 60 Plants of the Aleutian Islands, by Egbert H. Walker 63 Introduction 63 Principal plant associations 64 Plants of special interest or usefulness 68 The marine algae or seaweeds 70 Bibliography 72 Appendix A. List of mammals 75 B. List of birds 77 C. Keys to the birds 81 D. Systematic list of plants 96 E. Keys to the more common plants 110 ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES Page 1. Kiska Volcano 1 2. Upper, Aerial view of Unimak Island 4 Lower, Aerial view of Akun Head, Akun Island, Krenitzin group 4 3. Upper, U. S. Navy submarine docking at Dutch Harbor 4 Lower, Village of Unalaska 4 4. Upper, Aerial view of Cathedral Rocks, Unalaska Island 4 Lower, Naval air transport plane photographed against peaks of the Islands of Four Mountains 4 5. Upper, Mountain peaks of Kagamil and Uliaga Islands, Four Mountains group 4 Lower, Mount Cleveland, Chuginadak Island, Four Mountains group .. -

The Northwest Passage AUGUST 22 SEPTEMBER 7 & SEPTEMBER 7 23, 2020 2 Contents

EXPEDITION CRUISE The Northwest Passage AUGUST 22SEPTEMBER 7 & SEPTEMBER 723, 2020 2 Contents 5 Itinerary: Into the Northwest Passage 11 Itinerary: Out of the Northwest Passage SHIP 16 The Ocean Endeavour 18 Life Aboard the Ocean Endeavour PRICING, INCENTIVES, & REGISTRATION 20 Berth Prices 21 League of Adventurers & Incentives 22 Program Enhancements 23 Important Information Photography: Courtesy of Newfoundland & Labrador Tourism, Andrew Stewart, Jean Weller, Jason van Bruggen, Mike Beedell, Martin Aldrich, Scott Forsyth, Kristian Bogner, Craig Minielly, Dennis Minty, Andre Gallant, and Vladimir Rajevac 3 4 EXPEDITION CRUISE Into the Northwest Passage AUG.22SEPT. 7, 2020 Starts: Toronto, ON From $10,995 to $25,095 USD Ends: Calgary, AB per person (details pp.20) Aboard the Ocean Endeavour Charter Flights (details pp.20) ITINERARY Day 1: Kangerlussuaq, GL Day 2: Sisimiut Coast BEECHEY Day 3: Ilulissat ISLAND DEVON ISLAND GREENLAND TALLURUTIUP Day 4–5: Western Greenland VICTORIA PRINCE OF IMANGA LANCASTER ISLAND WALES ISLAND SOUND Day 6: At Sea — Davis Strait INLET IQALUKTUUTTIAQ PRINCE REGENT CORONATION (CAMBRIDGE BAY) Day 7: Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet), NU GULF QUEEN MAUD Mittimatalik GULF (Pond Inlet) Tallurutiup Imanga (Lancaster Kugluktuk Day 8–10: Uqsuqtuuq (Coppermine) BAFFIN Ilulissat (Gjoa Haven) ISLAND Sound) & Devon Island Sisimiut NUNAVUT Coast Day 11: Beechey Island Kangerlussuaq Day 12–13: Prince Regent Inlet CANADA DAVIS STRAIT Day 14–16: Kitikmeot Region Day 17: Kugluktuk, NU HIGHLIGHTS • Cross the Arctic Circle as you sail the length • Watch for marine mammals and wildlife in of Sondre Stromfjord—168 kilometres! Tallurutiup Imanga (Lancaster Sound) Marine • Cruise among icebergs at Ilulissat Icefjord, Protected Area a UNESCO World Heritage Site • Seek polar bears, seabirds, and other Arctic • Visit Queen Maud Gulf, home to the wrecks of wildlife in pristine natural environments the Franklin ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror Adventure Canada itineraries may be subject to change without notice due to weather, 5 ice, and sea conditions. -

An Archaeological View of the Thule / Inuit Occupation of Labrador

AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL VIEW OF THE THULE / INUIT OCCUPATION OF LABRADOR Lisa K. Rankin Memorial University May 2009 AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL VIEW OF THE THULE/INUIT OCCUPATION OF LABRADOR Lisa K. Rankin Memorial University May 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND .........................................................................................................................3 1. The Thule of the Canadian Arctic ......................................................................................3 2. A History of Thule/Inuit Archaeology in Labrador............................................................6 III. UPDATING LABRADOR THULE/INUIT RESEARCH ...................................................15 1. The Date and Origin of the Thule Movement into Labrador ...........................................17 2. The Chronology and Nature of the Southward Expansion...............................................20 3. Dorset-Thule Contact .......................................................................................................28 4. The Adoption of Communal Houses................................................................................31 5. The Internal Dynamics of Change in Inuit Society..........................................................34 IV. CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................................37 V. BIBLIOGRAPHY......................................................................................................................39 -

Wrangell Island Analysis Report 1 Stikine Area United States Forest Service Wrangell Ranger District

Wrangell Island Analysis Report Report Overview The purpose of this report is to solicit public review and comment and provide a context for future project decisions on National Forest lands on Wrangell Island over the next ten years. It presents an overview of public comments, resource conditions, and possible projects (roads and access management, timber harvest, recreation). This report describes Wrangell Island old growth reserves and other management prescriptions designated by the Forest Plan (TLMP). It describes wildlife travel corridors and recreation use across the island. It includes the results of a watershed analysis that identified sensitive watersheds and important fisheries on the island. Within this framework of Forest Plan prescriptions, resource conditions, and human use, an interdisciplinary team has suggested projects including: · Recreation trails and shelters. · Timber harvest proposals of one to five million board feet that avoid the most sensitive watersheds and allow consideration of scenery and wildlife values. · Road access management that considers wildlife and fisheries while maintaining access to potential timber sales and popular recreation sites. This report is organized as follows: · An introduction explaining why we wrote this report and how we intend to use it. · A summary of public comment and highlights of a Wrangell Island Analysis conducted by the 1997 Wrangell High School Environmental Sciences Class. · A summary of landscape design objectives from the Forest Plan. · Descriptions of the seven landscape -

30160105.Pdf

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2009/008 Document de recherche 2009/008 An Ecological and Oceanographical Évaluation écologique et Assessment of the Alternate Ballast océanographique de la zone Water Exchange Zone in the Hudson alternative pour l’échange des eaux Strait Region de ballast de la région du détroit d'Hudson D.B. Stewart and K.L. Howland Fisheries and Oceans Canada Central and Arctic Region, Freshwater Institute 501 University Crescent Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N6 This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of des écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle the day in the time frames required and the traite des problèmes courants selon les documents it contains are not intended as échéanciers dictés. Les documents qu’elle definitive statements on the subjects addressed contient ne doivent pas être considérés comme but rather as progress reports on ongoing des énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais investigations. plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans language in which they are provided to the la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit Secretariat. envoyé au Secrétariat. This document is available on the Internet at: Ce document est -

And Wrangell Mining Districts, Alaska

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR BTJXILETESr 347 THE AND WRANGELL MINING DISTRICTS, ALASKA BY FRED EUGENE WRIGHT AND CHARLES WILL WRIGHT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1908 CONTENTS. Page. Preface, by Alfred H. Brooks______1___________________ 9 Introduction __._________________________________ 11 General statement _"________________________,_____ 11 Field work________________________________ 12 Maps __ 13 Literature ________'_____________________________ 14 History of mining developments- ____________!__________ 16 Ketchikan mining district______ 16 AVraugell mining district __ _________________________ IS Production _ __ 19 Geographic sketch of southeastern Alaska__________________ 21 Geography of the Ketchikan and Wruugell districts __ _____ 22 General statement _______________________________ 22 Mainland belt _______ _ __.,____________ 23 Seaward islands : 26 Climatic conditions ______ _ __ _____ 27 Timber and vegetation__ __________^.__ 30' Distribution of timber _ ____ 30 Value of timber ______ _____ ______-______ ' 31 Growth of vegetation__'_ ___________ 31 National forest________________ _____________ 32 General geology of southeastern Alaska_____ ____________ 32 General statement ________ ____ 32 Stratigraphic succession_ _ _ _____ 33 Rock formations .____ ___________ 36 Structure : _____ 38 Mineral deposits______________ : __________ 41 Geology of the Ketchikan and Wrangell mining districts__________ 43 . Geologic maps __ _ __ 43 Sedimentary rocks.____ ,. 1 ____ 45