Short-Title Catalogs: the Current State of Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded 2021-09-28T10:41:52Z

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Lost books printed in French before 1601 Authors(s) Wilkinson, Alexander S. Publication date 2009-06 Publication information The Library, 10 (2): 188-205 Publisher Oxford University Press Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/3715 Publisher's statement This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in The Library following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version Wilkinson, Alexander S. Lost Books Printed in French before 1601. The Library, 10 (2): 188-205 first published online June 2009 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/library/10.2.188 is available online at: http://library.oxfordjournals.org/content/10/2/188.abstract Publisher's version (DOI) 10.1093/library/10.2.188 Downloaded 2021-09-28T10:41:52Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) © Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. 1 This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in The Library following peer review. The definitive publisher- authenticated version Alexander S Wilkinson, ‘Lost Books Printed in French before 1601’, The Library, 10/2 (2009), 188-205 is available online at: http://library.oxfordjournals.org/ content/10/2/188 2 Lost Books printed in French before 1601 ALEXANDER S. WILKINSON1 Abstract Research into the history of the book before 1601 has reached an important moment. -

CV Guidelines Regarding Publications

Guidelines for CV: Publications/Creative Activity Index Medicus: http://www2.bg.am.poznan.pl/czasopisma/medicus.php?lang=eng Reference in AHSL: American Medical Association (AMA) Manual of Style, 9th Edition (in reference section behind main desk) *Per Dave Piper, AHSL, underlining of titles is obsolete; italicization is preferred. Below guidelines were established for CoM Annual Report, not CVs in particular, but very similar. Books (scholarly books and monographs, authored or edited, conference proceedings): Author(s)/Editor(s)1; Book title (published conference proceedings go here – include conference title, dates & location); Publisher; Place of publication; Year of publication; Other identifying info Example – book/authors: Alpert JS, Ewy GA; Manual of Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA; 2002; 5th edition Example – book/editors: Becker RC, Alpert JS, eds; Cardiovascular Medicine – Practice and Management; Arnold Publishers; London, England; 2001 Chapters (chapters in scholarly books and monographs): Author(s)1; Chapter title; Pages3; Book title; Publisher; Place of publication; Year of publication2; (Other identifying info) Example – Book chapter: Alpert JS, Sabik JF, Cosgrove DM; Mitral valve disease; pp 483-508; In Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA; 2002; Topol, EJ, ed.; 2nd edition Example – Monograph: Alpert JS; Recent advances in the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction; 76:81-172; Monograph published in -

College and Research Libraries

Recent Publications I 83 tions. The guide itself is advertised at $35 ground. Professionally, the preferred com while Books in Print 1977/78 quotes a price bination of disciplines includes library sci of $17.50. At the latter price it should be in ence, psychology, and literature, with field every research library. service training recommended. Rubin For a detailed description of the guide quotes from several sources on each of the consult Dodson's article "Toward Biblio above points to demonstrate that the infor graphic Control: The Development of a mation on bibliotherapy is conflicting and Guide to Microform Research Collections" confusing. in Microform Review 7:'203-12 (July/Aug. In selecting materials for bibliotherapy, ~ 1978). At the present rate of new collections the content is more important than the publication, a more comprehensive and literary quality. The suggested juvenile streamlined second edition with cumulative books and films, arranged and cross updates would be welcome.-Leo R. Rift, referenced by topic, draw heavily from Ithaca College, Ithaca , New York. those of the last five years. An extensive, much-needed bibliography of poems, plays, Rubin, Rhea Joyce. Using Bibliotherapy: A short stories, films , and books for adults Guide to Theory and Practice. A Neal deals with subjects causing problems for Schuman Professional Book. Phoenix, them. Ariz. : Oryx Press, 1978. 245p. $11.95. LC In the companion volume, Bibliotherapy 78-9349. ISBN 0-912700-07-6. Sourcebook, Rubin gathers studies from var Bibliotherapy Sourcebook. Edited by Rhea ious sources and disciplines into a book to Joyce Rubin. A Neal-Schuman Profes fac ilitate research. -

Download Kindle \\ A.L.A. Booklist Volume 10

BJYSTRYBPPRS > Kindle A.L.A. Booklist Volume 10 A .L.A . Booklist V olume 10 Filesize: 9.13 MB Reviews This sort of pdf is everything and made me searching forward plus more. Better then never, though i am quite late in start reading this one. You may like just how the author compose this book. (Mae Jones) DISCLAIMER | DMCA B0HR27CK5I4I / PDF » A.L.A. Booklist Volume 10 A.L.A. BOOKLIST VOLUME 10 Not Avail, United States, 2012. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 246 x 189 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.This historic book may have numerous typos and missing text. Purchasers can download a free scanned copy of the original book (without typos) from the publisher. Not indexed. Not illustrated. 1914 Excerpt: .and to the general reader. Bibliographies (7p.) arranged according to the various writers. 804 Literature. Analytics for authors (6 cards) and bibliography 131449/10 Bullard, Arthur. The Barbary coast, by Albert Edwards. N. Y. Macmillan (S) 1913. 312p. illus. $2 net. Fieen graphic travel sketches of French North Africa, all but three written for the Outlook during the last twelve years. Besides the vivid reproduction of the physical aspects and atmosphere, the author gives interesting glimpses of the thoughts and philosophy of his eastern friends. The spirit of the region he has seized and given to us with charm and humor. 916.1 Barbary states Africa, North 13- 20787/4 Burgess, Thomas. Greeks in America. Bost.Sherman, French(0)1913. 256p. illus. $1.35 net. Discusses from the Greek s standpoint the early exodus from the mother country, the hardships, and later immigration from 1891 to 1913; the industrial, social and religious life here; and the character of communities in a number of cities. -

The Bibliographical Society of America Membership Application and Renewal Form

The Bibliographical Society of America Membership Application and Renewal Form Personal Details Membership Level (all fields required except where noted) (please check only one) Name: 35 & Under Membership, $25 Dr. Ms. Mrs. Mr. (circle one) Emerging bibliographers may join at a dis- counted rate. Partner Membership, $80 Dues cover the cost of the journal, our Mailing Address: meetings, and administration. Sustaining Membership, $125 Help sustain our programs for the future and support members entering our field. $ 45 is tax deductible. Leadership Membership, $250 Support expansion of our programs, further Phone Number: online development, and publications. $ 170 is tax deductible. Advancing Membership, $500 Advance our mission and our geographic Email Address: reach. $ 420 is tax deductible. Lifetime Membership, $1250 One-time contribution. Support our fellow- Which of these options best describe you? ship program and help us develop long- (check all that apply) range initiatives to support teaching and scholarship. $1,170 is tax deductible. Academic (Full-time Faculty, Admini- strator) Please note that all members receive: Academic (Part-time Faculty, Contingent, § A subscription to the quarterly Papers of the Biblio- Adjunct) graphical Society of America (PBSA) in print and e-Book Book Arts Worker formats, as well as online access to the full journal run. Book Collector § Discounted access to the ACLS Humanities eBook Collection for individuals. Bookseller § 30% discount on books published or distributed by Conservator the University of Chicago Press, and discounts on the Society’s other publications. Library Professional (Curator, Cataloger, Administrator) Would you like your contact information to be Library Professional (Para- or Pre- included in our membership directories? professional) (check all that apply) Museum Professional Include my name, title, and email address Retired in a membership directory available to the public. -

100 Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada Xvini 107, 109-I2

100 Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada xvInI 107, 109-I2, Io3 [i.e., 115], 116-23). Anomalous is the classing of the primarily literary bibliographies The Year's Work in Modern Language Studies (178) and Hatzfeld, A Crit- ical Bibliography of the New Stylistics (174) in the 'Special Categories - Linguistics' subsection. The question of precisely which specific works should be included in, or excluded from, a guide of this nature is most vexatious. I would only note, among the small number of useful titles omitted, such compendia of literary terminology as those of Berardi, Gildi, and Traversetti; compilations of proverbs such as those by Arthaber and Gluski; the excellent bibliographical Introduzione allo studio della lingua italiana of MuliaciE, the Dizionanio d'ortografiae di pronunzia of Bruno Migliorini et al., Parenti's Prime edizioni italiane, Pownall's Articles on ?Twentieth Century Literature, the Index to Book Reviews in the Humanities, perhaps Umberto Eco's Come si fa una tesi di laurea, and the neW MLA Handbook for Writers, vitiated admittedly by its paradoxically cavalier attitude to 'foreign' languages, nevertheless the generally received, particularly in North America, authority on matters of scholarly documentation. Its flaws notwithstanding (and bibliographies are not to be adjudged so much by the presence or absence of blemishes as by the number and hue thereof), Italian Reference Aids deserves to be put to thorough use by graduate students in Italian and Comparative Literature and could also find application -

MODULE 24: CATALOGUING PRACTICE: MULTI VOLUME BOOK in CCC and AACR-2R Dr. S.P. Sood Objectives of the Module 1. to Catalogue T

1 MODULE 24: CATALOGUING PRACTICE: MULTI VOLUME BOOK IN CCC AND AACR-2R Dr. S.P. Sood Objectives of the Module 1. To catalogue the Multi Volume book type 1 according to CCC and AACR-2R. 2. To catalogue the Multi Volume book type 2 according to CCC and AACR-2R. Key Words Cataloguing of Multi Volume book type 1, Cataloguing of Multi Volume book type 2. Structure of Module: E-Text 1. Introduction 2. Cataloguing Practice: Multi Volume book type 1 according to CCC and AACR-2R. 2.1 Complete set 2.2 Incomplete set 2.3 Uncomplete set 3. Cataloguing Practice: Multi Volume book type 2 according to CCC and AACR-2R. 3.1 Complete set 3.2 Incomplete set 3.3 Uncomplete set 3.4 Uncomplete and Incomplete set 4. Title pages for Practice 5. Further Readings 1. Introduction In previous module we have studied the definition of multi volume book, their types, and rules of cataloguing of both types according to CCC and AACR-2R. In this module we will learn cataloguing practice of both the type of multi volume books according to CCC and AACR-2R. 2 2. Cataloguing Practice: Multi Volume book type 1 according to CCC and AACR-2R. Title – 1 (Multi Volume type 1: Complete Set) SURVEY OF INDIAN BOOK INDUSTRY (in Two Volumes) RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT N.C.A.E.R. New Delhi, National Council of Applied Economic Research, 1975 Other Information Copyright by NCAER Call No. X8(M1).2’N74t4 Book No. Vol. I L5.1 Acc. No. 17511 Book No. -

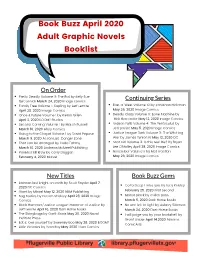

April Book Buzz AGN Booklist

Book Buzz April 2020 Adult Graphic Novels Booklist On Order Pretty Deadly Volume 3: The Rat by Kelly Sue Continuing Series DeConnick March 24, 2020 Image comics Family Tree Volume 1: Sapling by Jeff Lemire East of West Volume 10 by Jonathan Hickman April 28, 2020 Image Comics May 26, 2020 Image Comics Once & Future Volume 1 by Kieron Gillen Deadly Class Volume 9: Bone Machine by April 2, 2020 BOOM! Studios Rick Remender May 12, 2020 Image Comics Second Coming Volume 1 by March Russell Gideon Falls Volume 4: The Pentoculus by March 10, 2020 Ahoy Comics Jeff Lemire May 5, 2020 Image Comics Going to the Chapel Volume 1 by David Pepose Justice League Dark Volume 3: The Witching March 3, 2020 Action Lab-Danger Zone War by James Tynion IV May 12, 2020 DC That can be arranged by Huda Fahmy Snot Girl Volume 3: Is this real life? By Bryan March 10, 2020 Andrews McMeel Publishing Lee O’Malley April 28, 2020 Image Comics Punisher kill krew by Gerry Duggan November Volume II by Mat Fraction February 4, 2020 Marvel May 26, 2020 Image Comics New Titles Book Buzz Gems Batman last knight on earth by Scott Snyder April 7, Go to Sleep I miss you by Lucy Knisley 2020 DC Comics Giant by Mikael May 12, 2020 NBM Publishing February 25, 2020 First Second Bog Bodies by Declan Shalvey April 28, 2020 Image Manor Black by Cullen Bunn Comics March 5, 2020 Dark Horse Books Black Hammer/Justice League: Hammer of Justice by No one left to fight by Aubrey Sitterson Jeff Lemire April 16, 2020 Dark Horse Books March 24, 2020 Dark Horse Books The Stringbags by Garth Ennis May 20, 2020 Naval I will judge you by your bookshelf by Institute Press Grant Snider April 14.2020 Abrams Eat & love yourself by Sweeney Boo May 28, 2020 BOOM! ComicArts Little Victories by Yvon Roy May 2020 Titan Comics BOOK BUZZ ADULT NON-FICTION TITLES N o b o d y W i l l T e l l Y o u T h i s B u t M e b y B e s s K a l b M a r c h 1 7 , 2 0 2 0 s y W o w , N o T h a n k Y o u b y S a m a n t h a I r b y M a r c h 3 1 , 2 0 2 0 a s s H e r e F o r I t : O r , H o w t o S a v e Y o u r S o u l i n A m e r i c a b y R . -

Robert Shay (University of Missouri)

Manuscript Culture and the Rebuilding of the London Sacred Establishments, 1660- c.17001 By Robert Shay (University of Missouri) The opportunity to present to you today caused me to reflect on the context in which I began to study English music seriously. As a graduate student in musicology, I found myself in a situation I suspect is rare today, taking courses mostly on Medieval and Renaissance music. I learned to transcribe Notre Dame polyphony, studied modal theory, and edited Italian madrigals, among other pursuits. I had come to musicology with a background in singing and choral conducting, and had grown to appreciate—as a performer—what I sensed were the unique characteristics of English choral music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It was a seminar on the stile antico that finally provided an opportunity to bring together earlier performing and newer research interests. I had sung a few of Henry Purcell’s polyphonic anthems (there really are only a few), liked them a lot, and wondered if they were connected to earlier music by Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, and others, music which I soon came to learn Purcell knew himself. First for the above-mentioned seminar and then for my dissertation, I cast my net broadly, trying to learn as much as I could about Purcell and his connections to earlier English music. I quickly came to discover that the English traditions were, in almost every respect, distinct from the Continental ones I had been studying, ranging from how counterpoint was taught (or not taught) 1 This paper was delivered at a March 2013 symposium at Western Illinois University with the title, “English Cathedral Music and the Persistence of the Manuscript Tradition.” The present version includes some subsequent revisions and a retitling that I felt more accurately described the paper. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

A Quantitative Study of History in the English Short-Title Catalogue (ESTC), 1470–18001

Vol. 25, no. 2 (2015) 87–116 | ISSN: 1435-5205 | e-ISSN: 2213-056X A Quantitative Study of History in the English Short-Title Catalogue (ESTC), 1470–18001 Leo Lahti Laboratory of Microbiology, Wageningen University, The Netherlands [email protected] Niko Ilomäki Department of Computer Science, University of Helsinki, Finland [email protected] Mikko Tolonen Department of Modern Languages, University of Helsinki, Finland [email protected] Abstract This article analyses publication trends in the field of history in early modern Britain and North America in 1470–1800, based on English Short- Title Catalogue (ESTC) data.2 Its major contribution is to demonstrate the potential of digitized library catalogues as an essential scholastic tool and part of reproducible research. We also introduce a novel way of quantita- tively analysing a particular trend in book production, namely the publish- ing of works in the field of history. The study is also our first experimental analysis of paper consumption in early modern book production, and dem- onstrates in practice the importance of open-science principles for library and information science. Three main research questions are addressed: 1) who wrote history; 2) where history was published; and 3) how publishing changed over time in early modern Britain and North America. In terms This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License Uopen Journals | http://liber.library.uu.nl/ | URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-117388 Liber Quarterly Volume 25 Issue 2 2015 87 A Quantitative Study of History in the English Short-Title Catalogue (ESTC), 1470–1800 of our main findings we demonstrate that the average book size of history publications decreased over time, and that the octavo-sized book was the rising star in the eighteenth century, which is a true indication of expand- ing audiences. -

I22 Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 35 /I Robert

I22 Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 35 /I Robert Lecker. Making It Real: TI2e Canonization of Englisl2- Canadian Literature. Concord, Ont.: Anansi, 1995. xi, [I], 276 pp.; $22.95 (paper). IsBN 0-88784-566-5- Despite the assertion that in the 1960s 'government, academia, and the publishing industryjoined hands to create a national canon' (p.26), Robert Lecker's Making It Real: TI2e Canonization of English-CanadianLiterature places its primary focus on the critical writings of Canadian literary academics rather than govern- ment cultural policy or the activities of Canadian publishers. It's disappointing not to find publishing accorded a more integral role in canon formation through- out this volume. Moreover, Lecker's emphasis on the academic institution and the period after 1960 is troubling if one considers editors, book reviewers, or academics of earlier generations as having been engaged in canonical activities. Eight previously published and revised essays make up this book. They range from broadly conceived studies of canonization and its relation to English- Canadian literary criticism by academics, thr·ough examinations of particular activities, such as anthologies and a reprint series, to interpretive readings of Northrop Frye's Conclusion to the Literary History of Canadaand Frank Davey's 'Surviving the Paraphrase.' The book's introduction and conclusion, 'Making It Real' and 'Making It Real (Again),' like its title, allude to Robert Kroetsch's contention that 'The fiction makes us real.' Affirming a belief in the creative aspect of critical acts of writing, Lecker argues: 'Kroetsch is right: in any number of ways, people involved in writing about Canadian writing keep trying to con- struct their country, to write it into existence, to make it real' (p.