Downloaded 2021-09-28T10:41:52Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CV Guidelines Regarding Publications

Guidelines for CV: Publications/Creative Activity Index Medicus: http://www2.bg.am.poznan.pl/czasopisma/medicus.php?lang=eng Reference in AHSL: American Medical Association (AMA) Manual of Style, 9th Edition (in reference section behind main desk) *Per Dave Piper, AHSL, underlining of titles is obsolete; italicization is preferred. Below guidelines were established for CoM Annual Report, not CVs in particular, but very similar. Books (scholarly books and monographs, authored or edited, conference proceedings): Author(s)/Editor(s)1; Book title (published conference proceedings go here – include conference title, dates & location); Publisher; Place of publication; Year of publication; Other identifying info Example – book/authors: Alpert JS, Ewy GA; Manual of Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA; 2002; 5th edition Example – book/editors: Becker RC, Alpert JS, eds; Cardiovascular Medicine – Practice and Management; Arnold Publishers; London, England; 2001 Chapters (chapters in scholarly books and monographs): Author(s)1; Chapter title; Pages3; Book title; Publisher; Place of publication; Year of publication2; (Other identifying info) Example – Book chapter: Alpert JS, Sabik JF, Cosgrove DM; Mitral valve disease; pp 483-508; In Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA; 2002; Topol, EJ, ed.; 2nd edition Example – Monograph: Alpert JS; Recent advances in the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction; 76:81-172; Monograph published in -

College and Research Libraries

Recent Publications I 83 tions. The guide itself is advertised at $35 ground. Professionally, the preferred com while Books in Print 1977/78 quotes a price bination of disciplines includes library sci of $17.50. At the latter price it should be in ence, psychology, and literature, with field every research library. service training recommended. Rubin For a detailed description of the guide quotes from several sources on each of the consult Dodson's article "Toward Biblio above points to demonstrate that the infor graphic Control: The Development of a mation on bibliotherapy is conflicting and Guide to Microform Research Collections" confusing. in Microform Review 7:'203-12 (July/Aug. In selecting materials for bibliotherapy, ~ 1978). At the present rate of new collections the content is more important than the publication, a more comprehensive and literary quality. The suggested juvenile streamlined second edition with cumulative books and films, arranged and cross updates would be welcome.-Leo R. Rift, referenced by topic, draw heavily from Ithaca College, Ithaca , New York. those of the last five years. An extensive, much-needed bibliography of poems, plays, Rubin, Rhea Joyce. Using Bibliotherapy: A short stories, films , and books for adults Guide to Theory and Practice. A Neal deals with subjects causing problems for Schuman Professional Book. Phoenix, them. Ariz. : Oryx Press, 1978. 245p. $11.95. LC In the companion volume, Bibliotherapy 78-9349. ISBN 0-912700-07-6. Sourcebook, Rubin gathers studies from var Bibliotherapy Sourcebook. Edited by Rhea ious sources and disciplines into a book to Joyce Rubin. A Neal-Schuman Profes fac ilitate research. -

Download Kindle \\ A.L.A. Booklist Volume 10

BJYSTRYBPPRS > Kindle A.L.A. Booklist Volume 10 A .L.A . Booklist V olume 10 Filesize: 9.13 MB Reviews This sort of pdf is everything and made me searching forward plus more. Better then never, though i am quite late in start reading this one. You may like just how the author compose this book. (Mae Jones) DISCLAIMER | DMCA B0HR27CK5I4I / PDF » A.L.A. Booklist Volume 10 A.L.A. BOOKLIST VOLUME 10 Not Avail, United States, 2012. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 246 x 189 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.This historic book may have numerous typos and missing text. Purchasers can download a free scanned copy of the original book (without typos) from the publisher. Not indexed. Not illustrated. 1914 Excerpt: .and to the general reader. Bibliographies (7p.) arranged according to the various writers. 804 Literature. Analytics for authors (6 cards) and bibliography 131449/10 Bullard, Arthur. The Barbary coast, by Albert Edwards. N. Y. Macmillan (S) 1913. 312p. illus. $2 net. Fieen graphic travel sketches of French North Africa, all but three written for the Outlook during the last twelve years. Besides the vivid reproduction of the physical aspects and atmosphere, the author gives interesting glimpses of the thoughts and philosophy of his eastern friends. The spirit of the region he has seized and given to us with charm and humor. 916.1 Barbary states Africa, North 13- 20787/4 Burgess, Thomas. Greeks in America. Bost.Sherman, French(0)1913. 256p. illus. $1.35 net. Discusses from the Greek s standpoint the early exodus from the mother country, the hardships, and later immigration from 1891 to 1913; the industrial, social and religious life here; and the character of communities in a number of cities. -

Short-Title Catalogs: the Current State of Play

SHORT TITLE CATALOGUES: THE CURRENT STATE OF PLAY 121 KRK Short-Title Catalogs: The Current State of Play John Bloomberg-Rissman he output of the Anglophone press is covered by a series of projects, loosely known as short title catalogs. The major projects include: T l A Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland, & Ireland and of English Books Printed Abroad 1475–1640 (STC) 1 Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and British America and of English Books Printed in Other Countries 1641 1700 (Wing) 1 The English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC) 1 The Nineteenth Century Short Title Catalogue (NSTC) 1 The North American Imprints Program (NAIP) There are other short title catalog projects, such as the Cathedral Libraries Catalogue and English Catholic Books, 1701–1800 to name but two. Though these projects, and others like them, are arguably as worthy of discussion as any, it is not incorrect to see them as extensions of or supplements to the projects listed above. Volume 1 of the Cathedral Libraries Catalogue is in essence an extension of the can vass undertaken for STC and Wing, while volume 2 concerns itself with continen tal printing, and is therefore irrelevant in this context. English Catholic Books, 1701– 1800 is, in its own words, “a useful adjunct to the ESTC.”1 This paper will limit itself then to discussion of the bulleted projects, and will include up-to-date information on the status of each. The precursor to the first true short title catalog in the Anglophone world is usually considered to be the three-volume Catalogue of Books in the Library of the British Museum Printed in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and of Books in English Printed John Bloomberg-Rissman is Assistant Director for English projects (ESTC), Center for Bibliographical Studies and Research at the University of California, Riverside 121 122 RARE BOOKS & MANUSCRIPTS LIBRARIANSHIP Abroad, to the Year 1640 (Trustees of the British Museum, 1884). -

MODULE 24: CATALOGUING PRACTICE: MULTI VOLUME BOOK in CCC and AACR-2R Dr. S.P. Sood Objectives of the Module 1. to Catalogue T

1 MODULE 24: CATALOGUING PRACTICE: MULTI VOLUME BOOK IN CCC AND AACR-2R Dr. S.P. Sood Objectives of the Module 1. To catalogue the Multi Volume book type 1 according to CCC and AACR-2R. 2. To catalogue the Multi Volume book type 2 according to CCC and AACR-2R. Key Words Cataloguing of Multi Volume book type 1, Cataloguing of Multi Volume book type 2. Structure of Module: E-Text 1. Introduction 2. Cataloguing Practice: Multi Volume book type 1 according to CCC and AACR-2R. 2.1 Complete set 2.2 Incomplete set 2.3 Uncomplete set 3. Cataloguing Practice: Multi Volume book type 2 according to CCC and AACR-2R. 3.1 Complete set 3.2 Incomplete set 3.3 Uncomplete set 3.4 Uncomplete and Incomplete set 4. Title pages for Practice 5. Further Readings 1. Introduction In previous module we have studied the definition of multi volume book, their types, and rules of cataloguing of both types according to CCC and AACR-2R. In this module we will learn cataloguing practice of both the type of multi volume books according to CCC and AACR-2R. 2 2. Cataloguing Practice: Multi Volume book type 1 according to CCC and AACR-2R. Title – 1 (Multi Volume type 1: Complete Set) SURVEY OF INDIAN BOOK INDUSTRY (in Two Volumes) RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT N.C.A.E.R. New Delhi, National Council of Applied Economic Research, 1975 Other Information Copyright by NCAER Call No. X8(M1).2’N74t4 Book No. Vol. I L5.1 Acc. No. 17511 Book No. -

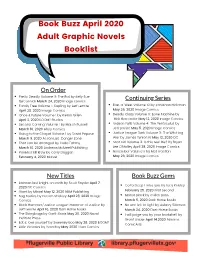

April Book Buzz AGN Booklist

Book Buzz April 2020 Adult Graphic Novels Booklist On Order Pretty Deadly Volume 3: The Rat by Kelly Sue Continuing Series DeConnick March 24, 2020 Image comics Family Tree Volume 1: Sapling by Jeff Lemire East of West Volume 10 by Jonathan Hickman April 28, 2020 Image Comics May 26, 2020 Image Comics Once & Future Volume 1 by Kieron Gillen Deadly Class Volume 9: Bone Machine by April 2, 2020 BOOM! Studios Rick Remender May 12, 2020 Image Comics Second Coming Volume 1 by March Russell Gideon Falls Volume 4: The Pentoculus by March 10, 2020 Ahoy Comics Jeff Lemire May 5, 2020 Image Comics Going to the Chapel Volume 1 by David Pepose Justice League Dark Volume 3: The Witching March 3, 2020 Action Lab-Danger Zone War by James Tynion IV May 12, 2020 DC That can be arranged by Huda Fahmy Snot Girl Volume 3: Is this real life? By Bryan March 10, 2020 Andrews McMeel Publishing Lee O’Malley April 28, 2020 Image Comics Punisher kill krew by Gerry Duggan November Volume II by Mat Fraction February 4, 2020 Marvel May 26, 2020 Image Comics New Titles Book Buzz Gems Batman last knight on earth by Scott Snyder April 7, Go to Sleep I miss you by Lucy Knisley 2020 DC Comics Giant by Mikael May 12, 2020 NBM Publishing February 25, 2020 First Second Bog Bodies by Declan Shalvey April 28, 2020 Image Manor Black by Cullen Bunn Comics March 5, 2020 Dark Horse Books Black Hammer/Justice League: Hammer of Justice by No one left to fight by Aubrey Sitterson Jeff Lemire April 16, 2020 Dark Horse Books March 24, 2020 Dark Horse Books The Stringbags by Garth Ennis May 20, 2020 Naval I will judge you by your bookshelf by Institute Press Grant Snider April 14.2020 Abrams Eat & love yourself by Sweeney Boo May 28, 2020 BOOM! ComicArts Little Victories by Yvon Roy May 2020 Titan Comics BOOK BUZZ ADULT NON-FICTION TITLES N o b o d y W i l l T e l l Y o u T h i s B u t M e b y B e s s K a l b M a r c h 1 7 , 2 0 2 0 s y W o w , N o T h a n k Y o u b y S a m a n t h a I r b y M a r c h 3 1 , 2 0 2 0 a s s H e r e F o r I t : O r , H o w t o S a v e Y o u r S o u l i n A m e r i c a b y R . -

Robert Shay (University of Missouri)

Manuscript Culture and the Rebuilding of the London Sacred Establishments, 1660- c.17001 By Robert Shay (University of Missouri) The opportunity to present to you today caused me to reflect on the context in which I began to study English music seriously. As a graduate student in musicology, I found myself in a situation I suspect is rare today, taking courses mostly on Medieval and Renaissance music. I learned to transcribe Notre Dame polyphony, studied modal theory, and edited Italian madrigals, among other pursuits. I had come to musicology with a background in singing and choral conducting, and had grown to appreciate—as a performer—what I sensed were the unique characteristics of English choral music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It was a seminar on the stile antico that finally provided an opportunity to bring together earlier performing and newer research interests. I had sung a few of Henry Purcell’s polyphonic anthems (there really are only a few), liked them a lot, and wondered if they were connected to earlier music by Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, and others, music which I soon came to learn Purcell knew himself. First for the above-mentioned seminar and then for my dissertation, I cast my net broadly, trying to learn as much as I could about Purcell and his connections to earlier English music. I quickly came to discover that the English traditions were, in almost every respect, distinct from the Continental ones I had been studying, ranging from how counterpoint was taught (or not taught) 1 This paper was delivered at a March 2013 symposium at Western Illinois University with the title, “English Cathedral Music and the Persistence of the Manuscript Tradition.” The present version includes some subsequent revisions and a retitling that I felt more accurately described the paper. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

A Quantitative Study of History in the English Short-Title Catalogue (ESTC), 1470–18001

Vol. 25, no. 2 (2015) 87–116 | ISSN: 1435-5205 | e-ISSN: 2213-056X A Quantitative Study of History in the English Short-Title Catalogue (ESTC), 1470–18001 Leo Lahti Laboratory of Microbiology, Wageningen University, The Netherlands [email protected] Niko Ilomäki Department of Computer Science, University of Helsinki, Finland [email protected] Mikko Tolonen Department of Modern Languages, University of Helsinki, Finland [email protected] Abstract This article analyses publication trends in the field of history in early modern Britain and North America in 1470–1800, based on English Short- Title Catalogue (ESTC) data.2 Its major contribution is to demonstrate the potential of digitized library catalogues as an essential scholastic tool and part of reproducible research. We also introduce a novel way of quantita- tively analysing a particular trend in book production, namely the publish- ing of works in the field of history. The study is also our first experimental analysis of paper consumption in early modern book production, and dem- onstrates in practice the importance of open-science principles for library and information science. Three main research questions are addressed: 1) who wrote history; 2) where history was published; and 3) how publishing changed over time in early modern Britain and North America. In terms This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License Uopen Journals | http://liber.library.uu.nl/ | URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-117388 Liber Quarterly Volume 25 Issue 2 2015 87 A Quantitative Study of History in the English Short-Title Catalogue (ESTC), 1470–1800 of our main findings we demonstrate that the average book size of history publications decreased over time, and that the octavo-sized book was the rising star in the eighteenth century, which is a true indication of expand- ing audiences. -

Manuscript Studies the Materiality of South Asian Manuscripts from The

Manuscript Studies Volume 1 Issue 1 Spring 2017 Article 3 2017 The Materiality of South Asian Manuscripts from the University of Pennsylvania MS Coll. 390 and the Rāmamālā Library in Bangladesh Benjamin J. Fleming University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mss_sims Part of the Library and Information Science Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Fleming, Benjamin J. (2017) "The Materiality of South Asian Manuscripts from the University of Pennsylvania MS Coll. 390 and the Rāmamālā Library in Bangladesh," Manuscript Studies: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mss_sims/vol1/iss1/3 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/mss_sims/vol1/iss1/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Materiality of South Asian Manuscripts from the University of Pennsylvania MS Coll. 390 and the Rāmamālā Library in Bangladesh Abstract The codex has become ubiquitous in the modern world as a common way of presenting the materiality of texts. Much of the scholarship on the History of the Book has taken this endpoint for granted even when discussing pre-modern writing and manuscript cultures. In this essay, I would like to open the discussion to other possibilities. I will draw on my research on medieval South Asian religions and from my hands-on work with manuscripts in two collections: the Rāmamālā Library in Bangladesh and the Indic collection at the University of Pennsylvania. Drawing examples from these two collections as well as noting broader patterns within them, this essay reflects on what South Asian manuscript traditions can contribute to our understanding of the materiality of texts. -

Robert Darnton, “What Is the History of Books?”

What is the History of Books? The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darnton, Robert. 1982. What is the history of books? Daedalus 111(3): 65-83. Published Version http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024803 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3403038 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ROBERT DARNTON What Is the History of Books? "Histoire du livre" in France, "Geschichte des Buchwesens" in Germany, "history of books" or "of the book" in English-speaking countries?its name varies from to as an new place place, but everywhere it is being recognized important even discipline. It might be called the social and cultural history of communica were not a to tion by print, if that such mouthful, because its purpose is were understand how ideas transmitted through print and how exposure to the printed word affected the thought and behavior of mankind during the last five hundred years. Some book historians pursue their subject deep into the period on before the invention of movable type. Some students of printing concentrate newspapers, broadsides, and other forms besides the book. The field can be most concerns extended and expanded inmany ways; but for the part, it books an area so since the time of Gutenberg, of research that has developed rapidly seems to a during the last few years, that it likely win place alongside fields like art canon the history of science and the history of in the of scholarly disciplines. -

Native American Children's Literature Recommended Reading List

Native American Children’s Literature Recommended Reading List Art by Julie Flett (Cree-Métis) OUR GUIDING PRINCIPLE We believe that when armed with the appropriate resources, Native peoples hold the capacity and ingenuity to ensure the sustainable economic, spiritual and cultural well-being of their communities. Native American Children’s Literature RECOMMENDED READING LIST BOOKS FOR HEAD Chukfi Rabbit’s Big Bad Bellyache: A Trickster Tale START AND PRESCHOOL by Greg Rodgers (Choctaw) Baby Learns About Colors (Cinco Puntos Press, 2014) by Beverly Blacksheep (Navajo) Jingle Dancer (Salina Bookshelf, 2003) by Cynthia Leitich Smith (Muscogee (Creek) (Morrow Junior Books, 2000) Wild Berries by Julie Flett (Cree-Métis) Kamik: An Inuit Puppy Story (Simply Read Books, 2013) by Donald Uluadluak (Inuit) (Inhabit Media, 2012) Boozhoo: Come Play With Us Cover art by Julie Flett by Deanna Himango (Ojibwe) SkySisters (Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior by Jan Bourdeau Waboose (Ojibwe) Chippewa, 2002) (Kids Can Press, 2000) Sweetest Kulu BOOKS FOR MIDDLE by Celina Kalluk (Inuit) (Inhabit Media, Inc., 2014) GRADES (4-7) Hidden Roots Cradle Me by Joseph Bruchac (Abenaki) Photos in book provided by Native families (Scholastic, 2004) and edited by Debby Slier. (Star Bright Books 2012) The Birchbark House by Louise Erdrich (Turtle Mountain My Heart Fills With Happiness Chippewa) by Monique Gray Smith (Cree, Lakota (Hyperion Books for Children, 1999) and Scottish) Cover art by Cornelius Van Wright (Orca Book Publishing, 2016) and Ying-Hwa Hu In the Footsteps