Termination of Transfer of Copyright: Able to Leap Trademarks in a Singe Bound?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Eyeclops Bionic Eye From

2007: the year in review THE “TOYING OF TECHNOLOGY” FocusingFocusing In:In: TheThe EyeClopsEyeClops®® BionicBionic EyeEye TakeTake itit toto thethe WebWeb GetGet MovingMoving THE YEAR OF HANNAH MONTANA® TOYS MICROECONOMICS ALSO IN TOYLAND TRENDTREND ALERT:ALERT: WHOWHO DOESN’TDOESN’T LOVELOVE CUPCAKES?CUPCAKES? AR 2007 $PRICELESS AR 2007 TABLE of CONTENTS JAKKS’ 4Girl POWER! In 2007 Disney® “It Girl” Miley Cyrus, a.k.a. Hannah Montana, hit the scene, and JAKKS was right there with her to catch the craze. Tween girls weren’t the only ones who took notice of the teen phenom. Hannah Montana toys from JAKKS were nominated for “Girls Toy of the Year” by the Toy Industry Association, received a 2008 LIMA licensing excellence award, and numerous retailers and media outlets also chose them as their top holiday picks for 2007. WIRED: SPOTLIGHT 6 on TECHNOLOGY From video game controllers to scientific magnifiers – in 2007 JAKKS expanded on its award-winning Plug It In & Play TV Games™ technology and created the EyeClops Bionic Eye, an innovative, handheld version of a traditional microscope for today’s savvy kids. JAKKS continued to amaze BOYS the action figure community will be by shipping more than 500 unique WWE® and BOYS Pokémon® figures to 8 retailers in more than 60 countries around the world in 2007. Joining the JAKKS powerhouse male action portfolio for 2008 and 2009 are The Chronicles of Narnia™: Prince Caspian™, American Gladiators®, NASCAR® and UFC Ultimate Fighting Championship® product lines, and in 2010… TNA® Total Non-Stop Action Wrestling™ toys. W e Hop e You E the Ne njoy w Ma gazine Format! - th 6 e editor 2007 ANNUAL REPORT THIS BOOK WAS PRINTED WITH THE EARTH IN MIND 2 JAKKS Pacifi c is committed to being a philanthropic and socially responsible corporate citizen. -

Spawn: the Eternal Prelude Darkness

Spawn: The Eternal Prelude Darkness. Pain. What . oh. Oh god. I'm alive! CHOOSE. What? Oh great God almighty in Heaven . NOT QUITE. CHOOSE. Choose . choose what? What are you? Where am I? Am I in Hell? NOT YET. DO YOU WISH TO RETURN? Yes! Yes, of course I want to go back! But . what's the catch? What is all this? IT IS NONE OF YOUR CONCERN. WHAT WOULD YOU GIVE FOR A RETURN? TO SEE YOUR LOVED ONES, TO ONCE MORE TASTE LIFE? WHAT WOULD YOU GIVE? I . I'm dead, aren't I? YES. But . what can I give? I am dead, so I have nothing! NOT TRUE. YOU HAVE YOURSELF. Myself? I don't understand . is it my soul you want? NO. I ALREADY HOLD YOUR SOUL . I WISH TO KNOW IF YOU WOULD SERVE ME WILLINGLY IN RETURN FOR COMING BACK. Serve . to see my wife again . yes . to hold my children once more . yes. I will serve you. VERY WELL. THE DEAL IS DONE . In a rainy graveyard, something fell smoking to the ground. It sat up, shaking its head, looking around itself. Strange. Why was he lying here? He tried to stand up, surprising himself by leaping at least twenty feet into the air, landing as smoothly as a cat. How . then something caught his attention. He stared into the puddle of rainwater, trying to discern the vague shape that must be his own face. And then he screamed. Because what stared back was the burn-scarred skullface of a corpse, its eyes glowing a deep green. -

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

MAY 4 Quadracci Powerhouse

APRIL 8 – MAY 4 Quadracci Powerhouse By David Bar Katz | Directed by Mark Clements Judy Hansen, Executive Producer Milwaukee Repertory Theater presents The History of Invulnerabilty PLAY GUIDE • Play Guide written by Lindsey Hoel-Neds Education Assistant With contributions by Margaret Bridges Education Intern • Play Guide edited by Jenny Toutant Education Director MARK’S TAKE Leda Hoffmann “I’ve been hungry to produce History for several seasons. Literary Coordinator It requires particular technical skills, and we’ve now grown our capabilities such that we can successfully execute this Lisa Fulton intriguing exploration of the life of Jerry Siegel and his Director of Marketing & creation, Superman. I am excited to build, with my wonder- Communications ful creative team, a remarkable staging of this amazing play that will equally appeal to theater-lovers and lovers of comic • books and superheroes.”” -Mark Clements, Artistic Director Graphic Design by Eric Reda TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopsis ....................................................................3 Biography of Jerry Siegel. .5 Biography of Superman .....................................................5 Who’s Who in the Play .......................................................6 Mark Clements The Evolution of Superman. .7 Artistic Director The Golem Legend ..........................................................8 Chad Bauman The Übermensch ............................................................8 Managing Director Featured Artists: Jef Ouwens and Leslie Vaglica ...............................9 -

The Adventure of the Shrinking Public Domain

ROSENBLATT_FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 2/12/2015 1:10 PM THE ADVENTURE OF THE SHRINKING PUBLIC DOMAIN ELIZABETH L. ROSENBLATT* Several scholars have explored the boundaries of intellectual property protection for literary characters. Using as a case study the history of intellectual property treatment of Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional character Sherlock Holmes, this Article builds on that scholarship, with special attention to characters that appear in multiple works over time, and to the influences of formal and informal law on the entry of literary characters into the public domain. While copyright protects works of authorship only for a limited time, copyright holders have sought to slow the entry of characters into the public domain, relying on trademark law, risk aversion, uncertainty aversion, legal ambiguity, and other formal and informal mechanisms to control the use of such characters long after copyright protection has arguably expired. This raises questions regarding the true boundaries of the public domain and the effects of non-copyright influences in restricting cultural expression. This Article addresses these questions and suggests an examination and reinterpretation of current copyright and trademark doctrine to protect the public domain from formal and informal encroachment. * Associate Professor and Director, Center for Intellectual Property Law, Whittier Law School. The author is Legal Chair of the Organization for Transformative Works, a lifelong Sherlock Holmes enthusiast, and a pro bono consultant on behalf of Leslie Klinger in litigation discussed in this Article. I would like to thank Leslie Klinger, Jonathan Kirsch, Hayley Hughes, Hon. Andrew Peck, and Albert and Julia Rosenblatt for their contributions to the historical research contained in this Article. -

Disentangling Immigrant Generations

THEORIZING AMERICAN GIRL ________________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ________________________________________________________________ by VERONICA E. MEDINA Dr. David L. Brunsma, Thesis Advisor MAY 2007 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THEORIZING AMERICAN GIRL Presented by Veronica E. Medina A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor David L. Brunsma Professor Mary Jo Neitz Professor Lisa Y. Flores DEDICATION My journey to and through the master’s program has never been a solitary one. My family has accompanied me every step of the way, encouraging and supporting me: materially and financially, emotionally and spiritually, and academically. From KU to MU, you all loved me and believed in me throughout every endeavor. This thesis is dedicated to my family, and most especially, to my parents Alicia and Francisco Medina. Mom and Dad: As a child, I often did not recognize and, far too often, took for granted the sacrifices that you made for me. Sitting and writing a thesis is a difficult task, but it is not as difficult as any of the tasks you two undertook to ensure my well-being, security, and happiness and to see me through to this goal. For all of the times you went without (and now, as an adult, I know that there were many) so that we would not, thank you. -

Home Décor & Collectable Auction

HOME DÉCOR & COLLECTABLE AUCTION (Online Bidding Available) Wednesday, February-14-18 5:00pm PREVIEW: Wednesday, February 14th,2018 2:00pm to 5:00pm #5-22720 Dewdney Trunk Rd, Maple Ridge, BC 17% buyer’s premium will be charged on purchases (2% discount on cash and debit purchases) All items are sold “as is, where is” No guarantees no warranties implied or given ALL SALES ARE FINAL – NO REFUNDS OR EXCHANGES All invoices must be paid in full on auction day by 4:30pm with cash, debit, Visa or MasterCard (TRANSACTIONS OVER $10,000 WILL REQUIRE PHOTO ID TO BE PHOTOCOPIED) Removal is by Thursday, February-15-18 until 4:00pm Doors will be open from 9am-4pm For more details, pictures & directions visit our website at: New to the Auction? *Here is a Detailed List of Some Terms You May Be Unfamiliar With* “Preview:” the preview is an allotted time in which the public can come to our warehouse and view the items they are interested in purchasing. This opportunity gives you the ability to inspect the product before bidding. Preview is usually the afternoon before and the morning of the auction; specific times can be found at www.ableauctions.ca “17%” or “Buyer’s Premium:” this is an additional fee added your bid price, it is charged due to the fact that the items that you are bidding on (most of which are BRAND NEW) are drastically below their regular retail price. It is a good idea to keep this in mind while bidding. There is a 2% discount on Cash and Debit Purchases. -

DECORATIVE SPECTER Noah Mcwilliams, Master of Fine Arts In

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: DECORATIVE SPECTER Noah McWilliams, Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art, 2021 Thesis directed by: Assistant Professor Cy Keener, Department of Art This exhibition reflects a tragic and anticlimactic future. The ultimate outcome of human exploration of the universe will no doubt shed light on the dismal nature of our interpersonal relationships and grand aspirations. Decorative Specter is an exhibition of sculpture and video that depicts a distant future inhabited by decorative artifacts of long extinct human civilizations. The works in this exhibition are speculative portraits of alien, but eerily familiar puppets. They represent moments within an implied overarching narrative, frozen for study and contemplation. My use of commonly overlooked aesthetics is intended to remind us that other intelligent life will likely spring from an unexpected place and with unexpected results. In the following text I will explain the formal qualities and concepts behind the work. DECORATIVE SPECTER by Noah Leonard McWilliams Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art 2021 Advisory Committee: Professor Cy Keener, Chair Professor Shannon Collis Professor Brandon Donahue Professor John Ruppert © Copyright by Noah Leonard McWilliams 2021 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

Finding Aid to the Stefanie Eskander Papers, 1986-2018

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Stefanie Eskander Papers Finding Aid to the Stefanie Eskander Papers, 1986-2018 Summary Information Title: Stefanie Eskander papers Creator: Stefanie Eskander (primary) ID: 118.8603 Date: 1986-2018 (inclusive); 1990s (bulk) Extent: 7.5 linear feet (physical); 130 MB (digital) Language: This collection is in English. Abstract: The Stefanie Eskander papers are a compilation of concept sketches, presentation drawings, and other artwork for dolls, toys, and games created by Eskander for various toy companies. The bulk of the materials are from the 1990s. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though the donor has not transferred intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) to The Strong, she has given permission for The Strong to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Custodial History: The Stefanie Eskander papers were donated to The Strong in August 2018 as a gift of Stefanie Clark Eskander. The papers were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 118.8603 and were received from Eskander in a portfolio and several oversized folders. Preferred citation for publication: Stefanie Eskander papers, Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong Processed by: Julia Novakovic, January 2019 Controlled Access Terms Personal Names • Eskander, Stefanie Corporate Names • Hasbro, Inc. -

S:\SGL\SUPERMAN\Really Final Draft to Pdf.Wpd

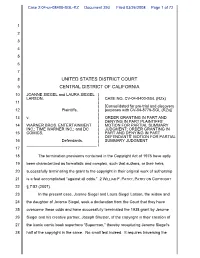

Case 2:04-cv-08400-SGL-RZ Document 293 Filed 03/26/2008 Page 1 of 72 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 JOANNE SIEGEL and LAURA SIEGEL ) LARSON, ) CASE NO. CV-04-8400-SGL (RZx) 11 ) ) [Consolidated for pre-trial and discovery 12 Plaintiffs, ) purposes with CV-04-8776-SGL (RZx)] ) 13 v. ) ORDER GRANTING IN PART AND ) DENYING IN PART PLAINTIFFS’ 14 WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT ) MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY INC.; TIME WARNER INC.; and DC ) JUDGMENT; ORDER GRANTING IN 15 COMICS, ) PART AND DENYING IN PART ) DEFENDANTS’ MOTION FOR PARTIAL 16 Defendants. ) SUMMARY JUDGMENT ) 17 18 The termination provisions contained in the Copyright Act of 1976 have aptly 19 been characterized as formalistic and complex, such that authors, or their heirs, 20 successfully terminating the grant to the copyright in their original work of authorship 21 is a feat accomplished “against all odds.” 2 WILLIAM F. PATRY, PATRY ON COPYRIGHT 22 § 7:52 (2007). 23 In the present case, Joanne Siegel and Laura Siegel Larson, the widow and 24 the daughter of Jerome Siegel, seek a declaration from the Court that they have 25 overcome these odds and have successfully terminated the 1938 grant by Jerome 26 Siegel and his creative partner, Joseph Shuster, of the copyright in their creation of 27 the iconic comic book superhero “Superman,” thereby recapturing Jerome Siegel’s 28 half of the copyright in the same. No small feat indeed. It requires traversing the Case 2:04-cv-08400-SGL-RZ Document 293 Filed 03/26/2008 Page 2 of 72 1 many impediments — many requiring a detailed historical understanding both 2 factually and legally of the events that occurred between the parties over the past 3 seventy years — to achieving that goal and, just as importantly, reckoning with the 4 limits of what can be gained through the termination of that grant.