Sure How Would the (Imminent) Future Ever Be After Becoming the (Recent) Past? Change in the Irish English" Be After V-Ing" Construction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old English: 450 - 1150 18 August 2013

Chapter 4 Old English: 450 - 1150 18 August 2013 As discussed in Chapter 1, the English language had its start around 449, when Germanic tribes came to England and settled there. Initially, the native Celtic inhabitants and newcomers presumably lived side-by-side and the Germanic speakers adopted some linguistic features from the original inhabitants. During this period, there is Latin influence as well, mainly through missionaries from Rome and Ireland. The existing evidence about the nature of Old English comes from a collection of texts from a variety of regions: some are preserved on stone and wood monuments, others in manuscript form. The current chapter focusses on the characteristics of Old English. In section 1, we examine some of the written sources in Old English, look at some special spelling symbols, and try to read the runic alphabet that was sometimes used. In section 2, we consider (and listen to) the sounds of Old English. In sections 3, 4, and 5, we discuss some Old English grammar. Its most salient feature is the system of endings on nouns and verbs, i.e. its synthetic nature. Old English vocabulary is very interesting and creative, as section 6 shows. Dialects are discussed briefly in section 7 and the chapter will conclude with several well-known Old English texts to be read and analyzed. 1 Sources and spelling We can learn a great deal about Old English culture by reading Old English recipes, charms, riddles, descriptions of saints’ lives, and epics such as Beowulf. Most remaining texts in Old English are religious, legal, medical, or literary in nature. -

Fragmentation and Vulnerability in Anne Enright´S the Green Road (2015): Collateral Casualties of the Celtic Tiger in Ireland

International Journal of IJES English Studies UNIVERSITY OF MURCIA http://revistas.um.es/ijes Fragmentation and vulnerability in Anne Enright´s The Green Road (2015): Collateral casualties of the Celtic Tiger in Ireland MARIA AMOR BARROS-DEL RÍO* Universidad de Burgos (Spain) Received: 14/12/2016. Accepted: 26/05/2017. ABSTRACT This article explores the representation of family and individuals in Anne Enright's novel The Green Road (2015) by engaging with Bauman's sociological category of “liquid modernity” (2000). In The Green Road, Enright uses a recurrent topic, a family gathering, to observe the multiple forms in which particular experiences seem to have suffered a process of fragmentation during the Celtic Tiger period. A comprehensive analysis of the form and plot of the novel exposes the ideological contradictions inherent in the once hegemonic notion of Irish family and brings attention to the different forms of individual vulnerability, aging in particular, for which Celtic Tiger Ireland has no answer. KEYWORDS: Anne Enright, The Green Road, Ireland, contemporary fiction, Celtic Tiger, mobility, fragmentation, vulnerability, aging. 1. INTRODUCTION Ireland's central decades of the 20th century featured a nationalism characterized by self- sufficiency and a marked protectionist policy. This situation changed in the 1960s and 1970s when external cultural influences through the media, growing flows of migration and economic transformations initiated by the government, together with the weakening of the Welfare State, progressively transformed a rural new-born country into an international _____________________ *Address for correspondence: María Amor Barros-del Río. Departamento de Filología. Facultad de Humanidades y Comunicación. Paseo de los Comendadores s/n. -

The Past, Present, and Future of English Dialects: Quantifying Convergence, Divergence, and Dynamic Equilibrium

Language Variation and Change, 22 (2010), 69–104. © Cambridge University Press, 2010 0954-3945/10 $16.00 doi:10.1017/S0954394510000013 The past, present, and future of English dialects: Quantifying convergence, divergence, and dynamic equilibrium WARREN M AGUIRE AND A PRIL M C M AHON University of Edinburgh P AUL H EGGARTY University of Cambridge D AN D EDIU Max-Planck-Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT This article reports on research which seeks to compare and measure the similarities between phonetic transcriptions in the analysis of relationships between varieties of English. It addresses the question of whether these varieties have been converging, diverging, or maintaining equilibrium as a result of endogenous and exogenous phonetic and phonological changes. We argue that it is only possible to identify such patterns of change by the simultaneous comparison of a wide range of varieties of a language across a data set that has not been specifically selected to highlight those changes that are believed to be important. Our analysis suggests that although there has been an obvious reduction in regional variation with the loss of traditional dialects of English and Scots, there has not been any significant convergence (or divergence) of regional accents of English in recent decades, despite the rapid spread of a number of features such as TH-fronting. THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF ENGLISH DIALECTS Trudgill (1990) made a distinction between Traditional and Mainstream dialects of English. Of the Traditional dialects, he stated (p. 5) that: They are most easily found, as far as England is concerned, in the more remote and peripheral rural areas of the country, although some urban areas of northern and western England still have many Traditional Dialect speakers. -

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

When to Start Receiving Retirement Benefits

2021 When to Start Receiving Retirement Benefits At Social Security, we’re often asked, “What’s the The following chart shows an example of how your best age to start receiving retirement benefits?” The monthly benefit increases if you delay when you start answer is that there’s not a single “best age” for receiving benefits. everyone and, ultimately, it’s your choice. The most important thing is to make an informed decision. Base Monthly Benefit Amounts Differ Based on the your decision about when to apply for benefits on Age You Decide to Start Receiving Benefits your individual and family circumstances. We hope This example assumes a benefit of $1,000 the following information will help you understand at a full retirement age of 66 and 10 months 1300 $1,253 how Social Security fits into your retirement decision. $1,173 $1,093 nt 1100 $1,013 ou $1,000 $944 $877 Am 900 Your decision is a personal one $811 $758 fit $708 Would it be better for you to start getting benefits ne 700 early with a smaller monthly amount for more years, y Be 500 or wait for a larger monthly payment over a shorter hl timeframe? The answer is personal and depends on nt several factors, such as your current cash needs, Mo your current health, and family longevity. Also, 0 consider if you plan to work in retirement and if you 62 63 64 65 66 66 and 67 68 69 70 have other sources of retirement income. You must 10 months also study your future financial needs and obligations, Age You Choose to Start Receiving Benefits and calculate your future Social Security benefit. -

Standard Southern British English As Referee Design in Irish Radio Advertising

Joan O’Sullivan Standard Southern British English as referee design in Irish radio advertising Abstract: The exploitation of external as opposed to local language varieties in advertising can be associated with a history of colonization, the external variety being viewed as superior to the local (Bell 1991: 145). Although “Standard English” in terms of accent was never an exonormative model for speakers in Ireland (Hickey 2012), nevertheless Ireland’s history of colonization by Britain, together with the geographical proximity and close socio-political and sociocultural connections of the two countries makes the Irish context an interesting one in which to examine this phenomenon. This study looks at how and to what extent standard British Received Pronunciation (RP), now termed Standard Southern British English (SSBE) (see Hughes et al. 2012) as opposed to Irish English varieties is exploited in radio advertising in Ireland. The study is based on a quantitative and qualitative analysis of a corpus of ads broadcast on an Irish radio station in the years 1977, 1987, 1997 and 2007. The use of SSBE in the ads is examined in terms of referee design (Bell 1984) which has been found to be a useful concept in explaining variety choice in the advertising context and in “taking the ideological temperature” of society (Vestergaard and Schroder 1985: 121). The analysis is based on Sussex’s (1989) advertisement components of Action and Comment, which relate to the genre of the discourse. Keywords: advertising, language variety, referee design, language ideology. 1 Introduction The use of language variety in the domain of advertising has received considerable attention during the past two decades (for example, Bell 1991; Lee 1992; Koslow et al. -

L Vocalisation As a Natural Phenomenon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Essex Research Repository L Vocalisation as a Natural Phenomenon Wyn Johnson and David Britain Essex University [email protected] [email protected] 1. Introduction The sound /l/ is generally characterised in the literature as a coronal lateral approximant. This standard description holds that the sounds involves contact between the tip of the tongue and the alveolar ridge, but instead of the air being blocked at the sides of the tongue, it is also allowed to pass down the sides. In many (but not all) dialects of English /l/ has two allophones – clear /l/ ([l]), roughly as described, and dark, or velarised, /l/ ([…]) involving a secondary articulation – the retraction of the back of the tongue towards the velum. In dialects which exhibit this allophony, the clear /l/ occurs in syllable onsets and the dark /l/ in syllable rhymes (leaf [li˘f] vs. feel [fi˘…] and table [te˘b…]). The focus of this paper is the phenomenon of l-vocalisation, that is to say the vocalisation of dark /l/ in syllable rhymes 1. feel [fi˘w] table [te˘bu] but leaf [li˘f] 1 This process is widespread in the varieties of English spoken in the South-Eastern part of Britain (Bower 1973; Hardcastle & Barry 1989; Hudson and Holloway 1977; Meuter 2002, Przedlacka 2001; Spero 1996; Tollfree 1999, Trudgill 1986; Wells 1982) (indeed, it appears to be categorical in some varieties there) and which extends to many other dialects including American English (Ash 1982; Hubbell 1950; Pederson 2001); Australian English (Borowsky 2001, Borowsky and Horvath 1997, Horvath and Horvath 1997, 2001, 2002), New Zealand English (Bauer 1986, 1994; Horvath and Horvath 2001, 2002) and Falkland Island English (Sudbury 2001). -

Abbey Theatre's

Under the leadership of Artistic Director Barbara Gaines and Executive Director Criss Henderson, Chicago A NOTE FROM DIRECTOR CAITRÍONA MCLAUGHLIN Shakespeare has redefined what a great American Shakespeare theater can be—a company that defies When Neil Murray and Graham McLaren (directors of theatrical category. This Regional Tony Award-winning the Abbey Theatre) asked me to direct Roddy Doyle’s theater’s year-round season features as many as twenty new play Two Pints and tour it to pubs around productions and 650 performances—including plays, Ireland, I was thrilled. As someone who has made musicals, world premieres, family programming, and presentations from around the globe. theatre in an array of found and site-sympathetic The work is enjoyed by 225,000 audience members annually, with one in four under the age of spaces, including pubs, shops, piers, beneath eighteen. Chicago Shakespeare is the city’s leading producer of international work, and touring flyovers, and one time inside a de-sanctified church, its own productions across five continents has garnered multiple accolades, including the putting theatre on in pubs around Ireland felt like a prestigious Laurence Olivier Award. Emblematic of its role as a global theater, the company sort of homecoming. I suspect every theatre director spearheaded Shakespeare 400 Chicago, celebrating Shakespeare’s legacy in a citywide, based outside of Dublin has had a production of yearlong international arts and culture festival, which engaged 1.1 million people. The Theater’s some sort or another perform in a pub, so why did nationally acclaimed arts in literacy programs support the work of English and drama teachers, this feel different? and bring Shakespeare to life on stage for tens of thousands of their students each school year. -

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge David Noel Wilson, B.A. Hon., Grad. Dip. Data Processing, Grad. Dip. History. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts (with Advanced Seminars component) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. July, 2004 © David N. Wilson 1 Abstract David Noel Wilson, Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge. This is a study of an early Irish heroic tale, the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of the Cooley). It examines the role and function of honour, both within the tale and within the society that produced the text. Its demonstrates how the pursuit of honour has influenced both the theme and structure of the Táin . Questions about honour and about the resolution of conflicting obligations form the subject matter of many of the heroic tales. The rewards and punishments of honour and shame are the primary mechanism of social control in societies without organised instruments of social coercion, such as a police force: these societies can be defined as being ‘honour-based’. Early Ireland was an honour- based society. This study proposes that, in honour-based societies, to act honourably was to act with ‘appropriate and balanced reciprocity’. Applying this understanding to the analysis of the Táin suggests a new approach to the reading the tale. This approach explains how the seemingly repetitive accounts of Cú Chulainn in single combat, which some scholars have found wearisome, serve to maximise his honour as a warrior in the eyes of the audience of the tale. -

Gaelic Biography: an Irish Experience Caint a Thug Diarmuid Breathnach in Ollscoil Ghlaschú

Gaelic biography: an Irish experience Caint a thug Diarmuid Breathnach in Ollscoil Ghlaschú Our work in Radio Telefís Éireann’s Sound Archives more than 40 years ago made Máire Ní Mhurchú and me more aware of the general shortage of Irish biographical information and especially with regard to the previous 40 years. There have been advances since: Oxford companions to Irish history and literature … and so on. But there are still no good biographical dictionaries of movements in Ireland’s recent history: revolutionary movements, politics; labour; theatre…. No matter how excellent the Royal Irish Academy’s Dictionary of Irish Biography will be – it’s due in November - it will not fill gaps which only dedicated dictionaries can. Bernard Canning’s Irish-born secular priests in Scotland 1829-1979 is one such dictionary. They were sent to Scotland mostly because of a surfeit of clergy in Ireland but also to enable Gáidhlic-speaking priests in the lowlands to move to Gáidhlic-speaking parishes. We would see the true national dictionary as biography by county, professions, politics, minorities, sport and so on…. all shelved cheek by jowl with the Academy’s volumes. In the so-called national dictionary, with its conventional principles, many fascinating people will be omitted. A dictionary of national biography deals with the famous, the infamous and the remembered. Dedicated dictionaries focus on people in various fields of endeavour, many, if not most of them, unknown nationally. In 1979 we became aware of the Academy’s plan for an national biography. The founding in 1882 of the Gaelic Journal is often seen as the beginning of the Irish language revival. -

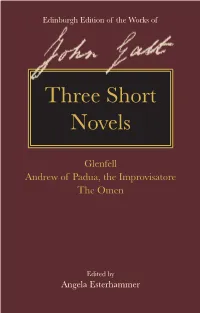

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

Fiction Relating to Ireland, 1800-29

CARDIFF CORVEY: READING THE ROMANTIC TEXT Archived Articles Issue 4, No 2 —————————— SOME PRELIMINARY REMARKS ON THE PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION OF FICTION RELATING TO IRELAND, 1800–1829 —————————— Jacqueline Belanger JACQUELINE BELANGER FICTION RELATING TO IRELAND, 1800–29 I IN 1829, just after Catholic Emancipation had been granted, Lady Morgan wrote: ‘Among the Multitudinous effects of Catholic emancipation, I do not hesitate to predict a change in the character of Irish authorship’.1 Morgan was quite right to predict a change in ‘Irish authorship’ after the eventful date of 1829, not least because, in the first and most obvious instance, one of the foremost subjects to have occupied the attentions of Irish authors in the first three decades of the early nineteenth century— Catholic Emancipation—was no longer such a central issue and attention was to shift instead to issues revolving around parliamentary independence from Britain. However, while important changes did occur after 1829, it could also be argued that the nature of ‘Irish authorship’—and in particular authorship of fiction relating to Ireland—was altering rapidly throughout the 1820s. It was not only the case that the number of novels representing Ireland in some form increased over the course of the 1820s, but it also appears that publishing of this type of fiction came to be dominated by male authors, a trend that might be seen to relate both to general shifts in the pattern for fiction of this time and to specific conditions in British expectations of fiction that sought to represent Ireland. It is in order to assess and explore some of the trends in the production and reception of fiction relating to Ireland during the period 1800–29 that this essay provides a bibliography of those novels with significant Irish aspects.